Medical Ethics and Law: Overlapping Concepts and Distinct Disciplines

NOTE: The UW Dept. of Bioethics & Humanities is in the process of updating all Ethics in Medicine articles for attentiveness to the issues of equity, diversity, and inclusion. Please check back soon for updates!

NOTE: The UW Dept. of Bioethics & Humanities is in the process of updating all Ethics in Medicine articles for attentiveness to the issues of equity, diversity, and inclusion. Please check back soon for updates!

Authors:

Lisa Vincler Brock, J.D., M.A.(Bioethics), Assistant Attorney General/Senior Counsel (retired), State of Washington

Anna Mastroianni, J.D., M.P.H., Charles I. Stone Emerita Professor of Law, University of Washington School of Law

Core Clerkship: General Curriculum

Introduction

Clinical ethics and law are disciplines with overlapping concepts, yet each discipline has unique parameters and a distinct focus. For example, the ethics concept of respect for autonomy is expressed in law as individual liberty. Each of these disciplines has its forums and authority; however, law may ultimately “resolve” a clinical ethics dilemma with a court order.

To better understand the relationship between ethics, law and risk management, these materials will briefly review:

- Introduction

- Understanding relationships: clinical ethics, law & risk management

- Orientation to law for non-lawyers

- Common clinical ethics issues

- Case studies highlighting the interplay between clinical ethics, legal & risk management issues

- Case 1: Disagreement among surrogate decision-makers/patient with advance directive/end of life/futility

- Case 2: Surrogate decision-maker with potential conflict of interest

- Case 3: Minor patient/Jehovah’s Witness/non-treatment against medical advice

Disclaimer

The information contained in this site is for general guidance only. The application and impact of laws, institutional risk management, and clinical ethics can vary widely based on the specific facts involved, institutional policies, and legal jurisdiction. In addition, law is not static in application and change can be expected as technology evolves and new issues emerge. The information on this site is provided with the understanding that the authors and publishers are not rendering legal, risk management, clinical ethics, or other professional advice and services. As such, the information in this article should not be used as a substitute for consultation with your own professional advisors. The opinions and views expressed herein have no relation to those of any institution with which the authors are or have been affiliated, and do not represent the opinions or views of the State of Washington Attorney General’s Office or the University of Washington. Neither the University nor its employees, nor any contributor to this web site, makes any representations, express or implied, with respect to the information provided herein or to its use.

II. Understanding relationships: clinical ethics, law & risk management.

A. Definitions and sources of authority

In the course of practicing medicine, a range of issues may arise that lead to consultation with a medical ethicist, a lawyer, and/or a risk manager. The following discussion will outline key distinctions between these roles.

- Clinical ethics may be defined as: a discipline or methodology for considering the ethical implications of medical technologies, policies, and treatments, with special attention to determining what ought to be done (or not done) in the delivery of health care.

- Law may be defined as: established and enforceable social rules for conduct or non-conduct; a violation of a legal standard may create criminal or civil liability.

- Risk Management may be defined as: a method of reducing risk of liability through institutional policies/practices.

Many health care facilities have in-house or on-call trained ethicists to assist health care practitioners, caregivers and patients with difficult issues arising in medical care, and some facilities have formally constituted institutional ethics committees. In the hospital setting, this ethics consultation or review process dates to at least 1992 with the formulation of accreditation requirements that mandated that hospitals establish a “mechanism” to consider clinical ethics issues1.

Ethics has been described as beginning where the law ends. The moral conscience is a precursor to the development of legal rules for social order. Ethics and law thus share the goal of creating and maintaining social good and have a symbiotic relationship as expressed in this quote:

[C]onscience is the guardian in the individual of the rules which the community has evolved for its own preservation. William Somerset Maugham 2

The role of lawyers and risk managers are closely linked in many health care facilities. Indeed, in some hospitals, the administrator with the title of Risk Manager is an attorney with a clinical background. There are, however, important distinctions between law and risk management. Risk management is guided by legal parameters but has a broader institution-specific mission to reduce liability risks. It is not uncommon for a hospital policy to go beyond the minimum requirements set by a legal standard. When legal and risk management issues arise in the delivery of health care, ethics issues may also exist. Similarly, an issue originally identified as falling within the clinical ethics domain may also raise legal and risk management concerns.

To better understand the significant overlap among these disciplines in the health care setting, consider the sources of authority and expression for each.

Ethical norms may be derived from:

- Law

- Institutional policies/practices

- Policies of professional organizations

- Professional standards of care, fiduciary obligations

Note: If a health care facility is also a religious facility, it may adhere to religious tenets. In general, however, clinical ethics is predominantly a secular professional analytic approach to clinical issues and choices.

Law may be derived from:

- Federal and state constitutions (fundamental laws of a nation or state establishing the role of government in relation to the governed)

- Federal and state statutes (laws written or enacted by elected officials in legislative bodies, and in some states, such as Washington and California, laws created by a majority of voters through an initiative process)

- Federal and state regulations (written by government agencies as permitted by statutory delegation, having the force and effect of law consistent with the enabling legislation)

- Federal and state case law (written published opinions of appellate-level courts regarding decisions in individual lawsuits)

- City or town ordinances, when relevant

Risk Management may be derived from law, professional standards and individual institution’s mission and public relations strategies and is expressed through institutional policies and practices.

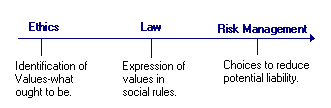

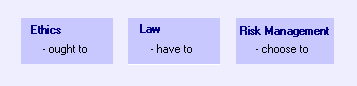

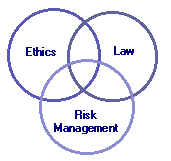

Another way to consider the relationship among the three disciplines is through conceptual models:

- Linear

- Distinctions

- Interconnectedness

III. Orientation to law for non-lawyers

A. Potential legal actions against health care providers

There are two primary types of potential civil actions against health care providers for injuries resulting from health care: (1) lack of informed consent, and (2) violation of the standard of care. Medical treatment and malpractice laws are specific to each state 3.

- Informed Consent. Before a health care provider delivers care, ethical and legal standards require that the patient provide informed consent. If the patient cannot provide informed consent, then, for most treatments, a legally authorized surrogate decision-maker may do so. In an emergency situation when the patient is not legally competent to give informed consent and no surrogate decision-maker is readily available, the law implies consent on behalf of the patient, assuming that the patient would consent to treatment if he or she were capable of doing so 4.

Information that must be conveyed to and consented to by the patient includes: the treatment’s nature and character and anticipated results, alternative treatments (including non-treatment), and the potential risks and benefits of treatment and alternatives. The information must be presented in a form that the patient can comprehend (i.e., in a language and at a level which the patient can understand) and that the consent must be voluntarily given. An injured patient may bring an informed consent action against a provider who fails to obtain the patient’s informed consent in accordance with state law. 5.

From a clinical ethics perspective, informed consent is a communication process, and should not simply be treated as a required form for the patient’s signature. Similarly, the legal concept of informed consent refers to a state of mind, i.e., understanding the information provided to make an informed choice. Health care facilities and providers use consent forms to document the communication process. From a provider’s perspective, a signed consent form can be valuable evidence the communication occurred and legal protection in defending against a patient’s claim of a lack of informed consent. Initiatives at the federal level (i.e., the Affordable Care Act) and state level (e.g., Revised Code of Washington § 7.70.060) reflect approaches that support shared decision-making and the use of patient decision aids in order to ensure the provision of complete information for medical decision-making.

- Failure to follow standard of care. A patient who is injured during medical treatment may also be able to bring a successful claim against a health care provider if the patient can prove that the injury resulted from the provider’s failure to follow the accepted standard of care. The duty of care generally requires that the provider uses reasonably expected knowledge and judgment in the treatment of the patient, and typically would also require the adept use of the facilities at hand and options for treatment. The standard of care emerges from a variety of sources, including professional publications, interactions of professional leaders, presentations and exchanges at professional meetings, and among networks of colleagues. Experts are hired by the litigating parties to assist the court in determining the applicable standard of care.

Many states measure the provider’s actions against a national standard of care (rather than a local one) but with accommodation for practice limitations, such as the reasonable availability of medical facilities, services, equipment and the like. States may also apply different standards to specialists and to general practitioners. As an example of a statutory description of the standard of care, Washington State currently specifies that a health care provider must "exercise that degree of care, skill, and learning expected of a reasonably prudent health care provider at that time in the profession or class to which he belongs, in the State of Washington, acting in the same or similar circumstances.” 6

B. The litigation process: a brief summary

There are essentially three distinct phases to the litigation process: (1) initiation, (2) pre-trial, and (3) trial and post-trial. The possibility that the parties will reach an agreement about the legal claims before or during trial, known as a settlement, means that the vast majority of initiated claims do not go through all three phases. An understanding of the litigation process and its accompanying vocabulary can be helpful in providing a fuller understanding of the intersection of law, clinical ethics, and risk management.

- Initiation phase: A lawsuit will begin when the plaintiff (an allegedly injured patient) files a complaint (claim) with the court. The plaintiff is obligated to legally notify (serve) the defendant(s) (e.g., the health care provider) with a summons and the complaint on the defendant. Medical malpractice lawsuits frequently include more than one defendant and may be made against more than one provider, institution, and manufacturer of medical equipment and/or pharmaceutical companies. In the complaint, the plaintiff presents the facts that are the basis for the lawsuit. The defendant is required to file an answer (written response) with the court, and to also provide the plaintiff with a copy within a specified period of time.

- Pre-trial phase: After filing a lawsuit and before trial, both sides (plaintiff and defendant) gather information using various methods known as discovery. Discovery methods used may include interrogatories, which are written questions that the opposing side must answer under oath. Requests for production require the opposing side to provide documents to the other side. Requests for admissions require the opposing side to state that some facts are true before trial. Witnesses can be required to answer questions in person under oath, known as a deposition, and may also be required to bring documents to the deposition. Although the information collected during discovery prepares the parties for trial, it also can be used as a basis for settlement. Indeed, most civil lawsuits, including actions against health care providers, are settled and never go to trial before a judge or jury 7. Some cases are resolved by summary judgment, in which the court decides in favor of one party based on information derived during the discovery process. To encourage the parties to find a resolution to a health care dispute before trial, a few states require the parties to submit to mediation 8.

- Trial and post-trial phase. Cases involving injuries in health care are typically decided by a jury. However, cases involving federal health care facilities (and their employees), such as the Veterans Health Administration, are decided by a judge 9. A trial in front of a jury will involve the following, in this order: jury selection; opening statements by both parties; plaintiff’s trial testimony; defendant’s trial testimony; closing arguments; jury instructions (argued by legal counsel to the judge, determined by the judge, and designed to guide the jury in decision-making); jury deliberation; and, verdict. Even after a jury verdict, there may be post-trial motions to the judge which could alter the outcome of the case.

C. How and where to find the law on a particular topic 10

Law is dynamic—it is constantly evolving and changing, and this is particularly true in health law. Courts and legislatures respond to new issues and technologies by creating new laws or applying and interpreting existing laws. The changing nature of the law prompts a caveat to legal researchers: material obtained through general legal searches may not be current and the state of the law should be confirmed with a practicing lawyer before relying upon it. The internet offers many helpful resources to orient non-lawyers to locating relevant law, several of which are described below.

- The American Association of Law Libraries offers a practical guide for non-lawyers on researching a legal problem: American Association of Law Libraries “How to Research a Legal Problem: A Guide for Non-Lawyers” (revised 2022): How to Research a Legal Problem: A Guide for Non-Lawyers - AALL (aallnet.org).

- Another online resource on legal research for the non-lawyer audience is available through Nolo Press: Laws and Legal Research (updated 4 June 2024).

- For a basic outline of the structure of the American legal system, FindLaw has prepared a guide titled “The U.S. Legal System” by Mark F. Radcliffe and Diane Brinson of the law firm DLA Piper (2008): The U.S. Legal System - FindLaw

In addition, a number of useful resources are available in hard-copy or eBook format, two of which are mentioned below.

- Law 101: Everything You Need to Know About the American Legal System, 3d ed. (Oxford University Press, 2018). Available at University of Washington School of Law Library in eBook or hard copy (KF387.F45 2018 in Classified Stacks).

- American Law: An Introduction (Oxford Univ. Press 2017). eBook available through University of Washington School of Law Library. Earlier hard copy editions are also available (KF387.F74 1998 at Classified Stacks).

Reference librarians at law schools, particularly at public institutions, may be helpful in locating specific documents or orienting an interested person to the law. Specific statutes, regulations or case law may also be available on official government websites. In addition, medical journals (available on the internet or in medical school libraries) frequently have articles on clinical ethics or policy issues in health care which often address relevant legal authority.

IV. Common clinical ethics issues: medical decision-making and provider-patient communication

There are a number of common ethical issues that also implicate legal and risk management issues. Briefly discussed below are common issues that concern medical decision-making and provider-patient communication.

If a patient is capable of providing informed consent, then the patient’s choices about treatment, including non-treatment, should be followed. This is an established and enforceable legal standard and also consistent with the ethical principle of respecting the autonomy of the patient. The next two sections (Surrogate decision-making; Advance directives) discuss how this principle is respected from a legal perspective if a patient lacks capacity, temporarily or permanently, to make medical decisions. The third section briefly introduces the issue of provider-patient communication, and highlights a contemporary dilemma raised in decisions regarding the disclosure of medical error to patients.

The determination as to whether a patient has the capacity to provide informed consent is generally a professional judgment made and documented by the treating health care provider. The provider can make a determination of temporary or permanent incapacity, and that determination should be linked to a specific decision. The legal term competency (or incompetency) may be used to describe a judicial determination of decision-making capacity. The designation of a specific surrogate decision-maker may either be authorized by court order or is specified in state statutes.If a court has determined that a patient is incompetent, a health care provider must obtain informed consent from the court-appointed decision-maker. For example, where a guardian has been appointed by the court in a guardianship action, a health care provider would seek the informed consent of the guardian, provided that the relevant court order covers personal or health care decision-making.

If a court has determined that a patient is incompetent, a health care provider must obtain informed consent from the court-appointed decision-maker. For example, where a guardian has been appointed by the court in a guardianship action, a health care provider would seek the informed consent of the guardian, provided that the relevant court order covers personal or health care decision-making.

If, however, a physician determines that a patient lacks the capacity to provide informed consent, for example, due to dementia or lack of consciousness, or because the patient is a minor and the minor is legally proscribed from consenting, then a legally authorized surrogate decision-maker may be able to provide consent on the patient’s behalf. Most states have specific laws that delineate, in order of priority, who can be a legally authorized surrogate decision-maker for another person. While these laws may vary, they generally assume that legal relatives are the most appropriate surrogate decision-makers. If, however, a patient has previously, while capable of consenting, selected a person to act as her decision-maker and executed a legal document known as a durable power of attorney for health care or health care proxy, then that designated individual should provide informed consent.

In Washington State, a statute specifies the order of priority of authorized decision-makers as follows, with some conditions: guardian, holder of durable power of attorney; spouse or state registered partner; adult children; parents; adult brothers and sisters; adult grandchildren; nieces and nephews; aunts and uncles; and an adult that has exhibited special care and concern for the patient. If the patient is a minor, other consent provisions may apply, such as: court authorization for a person with whom the child is in out-of-home placement; the person(s) that the child’s parent(s) have given a signed authorization to provide consent; or, a competent adult who represents that s/he is a relative responsible for the child’s care and signs a sworn declaration stating so. 11 Health care providers are required to make reasonable efforts to locate a person in the highest possible category to provide informed consent. If there are two or more persons in the same category, e.g., adult children, then the medical treatment decision must be unanimous among those persons. 12 A surrogate decision-maker is required to make the choice she believes the patient would have wanted, which may not be the choice the decision-maker would have chosen for herself in the same circumstance. This decision-making standard is known as substituted judgment. 13 If the surrogate is unable to ascertain what the patient would have wanted, then the surrogate may consent to medical treatment or non-treatment based on what is in the patient's best interest. 14

Laws on surrogate decision-making are beginning to catch up with social changes. Non-married couples have not traditionally been recognized in state law as legally authorized surrogate decision-makers. This lack of recognition has left providers in a difficult legal position, encouraging them to defer to the decision-making of a distant relative over a spouse-equivalent unless the relative concurs. Washington law, for example, recognizes spouses and domestic partners registered with the state as having the same priority status, and also recognizes the potential decisionmaking authority of an adult who has “exhibited special care and concern for the patient” and is “familiar with the patient’s personal values,” subject to specified conditions 15

Parental decision-making and minor children. A parent may not be permitted in certain situations to consent to non-treatment of his or her minor child, particularly where the decision would significantly impact and perhaps result in death if the minor child did not receive treatment. Examples include parents who refuse medical treatment on behalf of their minor children because of the parents’ social or religious views, such as Jehovah’s Witnesses and Christian Scientists. The decision-making standard that generally applies to minor patients in such cases is known as the best interest standard. The substituted judgment standard may not apply because the minor patient never had decision-making capacity and therefore substituted judgment based on the minor’s informed choices is not able to be determined. It is important to note that minors may have greater authority to direct their own care depending on their age, maturity, nature of medical treatment or non-treatment, and may have authority to consent to specific types of treatment. For example, in Washington State, a minor may provide his or her own informed consent for treatment of mental health conditions, sexually transmitted diseases, and birth control, among others. Depending on the specific facts, a health care provider working with the provider’s institutional representatives could potentially legally provide treatment of a minor under implied consent for emergency with documentation of that determination, 16 assume temporary protective custody of the child under child neglect laws, or if the situation is non-urgent, the provider could seek a court order to authorize treatment.

The term advance directive refers to several different types of legal documents that may be used by a patient while competent to record future wishes in the event the patient lacks decision-making capacity. The choice and meaning of specific advance directive terminology is dependent on state law. Generally, a living will expresses a person’s desires concerning medical treatment in the event of incapacity due to terminal illness or permanent unconsciousness. A durable power of attorney for health care or health care proxy appoints a legal decision-maker for health care decisions in the event of incapacity. An advance health care directive or health care directive may combine the functions of a living will and durable power of attorney for health care into one document in one state, but may be equivalent to a living will in another state. The Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST) form, also referred to as Portable Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment is a document that is signed by a physician and patient which summarizes the patient’s wishes concerning medical treatment at the end of life, such as resuscitation, antibiotics, other medical interventions and artificial feeding, and translates them into medical orders that follow patients regardless of care setting. It is especially helpful in effectuating a patient’s wishes outside the hospital setting, for example, in a nursing care facility or emergency medical response context. Programs may operate under different names: POST (Physician or Portable Orders for Scope of Treatment), MOST (Medical Orders for Scope of Treatment), MOLST (Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment), and COLST (Clinician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment). The simple one-page treatment orders follow patients regardless of care setting. Thus, it differs from an advance directive because it is written up by the clinician in consultation with the patient and is a portable, actionable medical order. The POLST form is intended to complement other forms of advance directives. For example, Washington State recognizes the following types of advance directives: the health care directive (living will), the durable power of attorney for health care, and the POLST form. 17 Washington also recognizes another legal document known as a mental health advance directive, which can be prepared by individuals with mental illness who fluctuate between capacity and incapacity for use during times when they are incapacitated. 18

State laws may also differ on the conditions that can be covered by an individual in an advance directive, the procedural requirements to ensure that the document is effective (such as the number of required witnesses) and the conditions under which it can be implemented (such as invalidity during pregnancy).

Advance directives can be very helpful in choosing appropriate treatment based upon the patient’s expressed wishes. There are situations, however, in which the advance directive’s veracity is questioned or in which a legally authorized surrogate believes the advance directive does not apply to the particular care decision at issue. Such conflicts implicate clinical ethics, law and risk management.

C. Provider-Patient communications: Disclosing medical error

Honest communication to patients by health care providers is an ethical imperative. Excellent communication eliminates or reduces the likelihood of misunderstandings and conflict in the health care setting, and also may affect the likelihood that a patient will sue.

One of the more contentious issues that has arisen in the context of communication is whether providers should disclose medical errors to patients, and if so, how and when to do so. Disclosure of medical error creates a potential conflict among clinical ethics, law and risk management. Despite a professional ethical commitment to honest communication, providers cite a fear of litigation as a reason for non-disclosure. Specifically, the fear is that those statements will stimulate malpractice lawsuits or otherwise be used in support of a claim against the provider. An increase in malpractice claims could then negatively affect the provider’s claims history and malpractice insurance coverage.

There is some evidence in closed systems (one institution, one state with one malpractice insurer) that an apology coupled with disclosure and prompt payment may decrease either the likelihood or amount of legal claim. In addition, a number of state legislatures have acted to protect provider apologies, or provider apologies coupled with disclosures, from being used by a patient as evidence of a provider’s liability in any ensuing malpractice litigation. 19 The impact of those laws on the size or frequency of medical malpractice claims in multiple settings is a subject of ongoing evaluation. 20 For this reason and others, it is advisable to involve risk management and legal counsel in decision-making regarding error disclosure.

REFERENCES

[1] Sharon E. Caulfield, Health Care Facility Ethics Committees: New Issues in the Age of Transparency, ABA Human Rights Magazine, Fall 2007 Vol. 34, No. 4 Available at: https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazi.... Accessed 22 August 2024.

[2] W. Somerset Maugham, The Moon and Sixpence (New York: Grossett & Dunlap Publishers, 1919), 80.

[3] Where relevant, Washington state law will be referenced as an example in this discussion. See, generally, Revised Code of Washington, Chapter 7.70, http://apps.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=7.70

[4] Each institution should have a policy that defines “emergency” in accordance with state law and lays out institutional documentation requirements so that providers are guided in their decision-making. Where there is no definition of ”emergency” in state law or institutional policies, institutions and courts may be guided by the definition found in the federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA, also referenced as COBRA) which provides:

- The term “emergency medical condition” means--

- a medical condition manifesting itself by acute symptoms of sufficient severity (including severe pain) such that the absence of immediate medical attention could reasonably be expected to result in--

- placing the health of the individual (or, with respect to a pregnant woman, the health of the woman or her unborn child) in serious jeopardy

- serious impairment to bodily functions, or

- serious dysfunction of any bodily organ or part; or

- with respect to a pregnant woman who is having contractions--

- that there is inadequate time to effect a safe transfer to another hospital before delivery, or

- that transfer may pose a threat to the health or safety of the woman or the unborn child.

- a medical condition manifesting itself by acute symptoms of sufficient severity (including severe pain) such that the absence of immediate medical attention could reasonably be expected to result in--

42 U.S.C 1395dd(e)(1).

[5] See Revised Code of Washington § 7.70.050, http://apps.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=7.70.050. Accessed 22 August 2024.

[6] See Revised Code of Washington § 7.70.040, http://apps.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=7.70.040. Accessed 22 August 2024.

[7] “Among jurisdictions that provided totals for both trial and non-trial general civil dispositions in 2005, trials collectively accounted for about 3% of all tort, contract, and real property dispositions in general jurisdiction courts.” LYNN LANGTON & THOMAS H. COHEN, CIVIL BENCH AND JURY TRIALS IN STATE COURTS, 2005, at 1 (2008), available at https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/cbjtsc05.pdf. Accessed 22 August 2024.

[8] Florence Yee, Mandatory Mediation: The Extra Dose Needed to Cure the Medical Malpractice Crisis, 7 CARDOZO J. CONFLICT RESOL. 393, 432-33 (2006).

[9] A federal health facility and its employees would be subject to the Federal Torts Claims Act (FTCA). 28 U.S.C. § 2402. Lawsuits against the United States under the FTCA are tried without a jury. Lester Jayson, Handling Federal Tort Claims: administrative and judicial remedies § 16.08 (Mathew Bender and Company 2011).

[10] The authors gratefully acknowledge the research support of the Reference Librarians at the University of Washington School of Law in drafting this section.

[11] Revised Code of Washington § 7.70.065 (2) (a), http://apps.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=7.70.065. Accessed 15 November 2011.

[12] See Revised Code of Washington § 7.70.065, http://apps.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=7.70.065. Accessed 22 August 2024.

[13] See, for example, in Washington State the case In re Ingram, 102 Wn.2d 827, 689 P.2d 1363 (1984). This Washington Supreme Court decision establishes in state law the substituted judgment standard and articulates the countervailing interests of the State in weighing whether an incapacitated patient’s choice for treatment or non-treatment may be overridden. Under substituted judgment, a court directs the course of medical treatment for an incompetent by determining the treatment the incompetent would choose if he were competent to make the decision and weighing that determination against any compelling State interests, including: preservation of life, protection of the interests of innocent third parties, the prevention of suicide, and the maintenance of the ethical integrity of the medical profession.

[14] Revised Code of Washington § 7.70.065 (1)(c), http://apps.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=7.70.065. Accessed 22 August 2024.

[15] See Revised Code of Washington § 7.70.065(1)(a)(iii), http://apps.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=7.70.065. Accessed 22 August 2024.

[16] See Discussion of Case #2. For example, Washington State law provides for "implied consent" for emergency treatment situations: If a recognized health care emergency exists and the patient is not legally competent to give an informed consent and/or a person legally authorized to consent on behalf of the patient is not readily available, his or her consent to required treatment will be implied. Revised Code of Washington § 7.70.050(4), http://apps.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=7.70.050. Accessed 22 August 2024. However, the hospital policy may be more specific and include an institutional documentation standard.

[17] See Revised Code of Washington Chapter 70.122, http://apps.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=70.122. Accessed 22 August 2024. Non-married individuals may also wish to complete a hospital authorization form in advance to ensure that they are permitted to visit a patient as a family member regardless of hospital policy.

[18] See Revised Code of Washington, Chapter 71.32, http://apps.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=71.32. Accessed 22 August 2024.

[19] See e.g., Mastroianni A., Mello M, Sommer S, Hardy M. Gallagher T. 2010. “The Flaws in State ‘Apology’ And ‘Disclosure’ Laws Dilute Their Intended Impact on Malpractice Suits,” Health Affairs 29(9): 1611-19.

[20] See e.g., Benjamin J. McMichael, R. Lawrence Van Horn & W. Kip Viscusi. “Sorry” Is Never Enough: How State Apology Laws Fail to Reduce Medical Malpractice Liability Risk, 71 Stan. L. Rev. 341 (2019). https://review.law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/02/McMic.... Accessed 22 August 2024.

[21] Washington's Natural Death Act currently defines the terms "terminal condition," "permanent unconscious condition" and "life-sustaining treatment," Revised Code of Washington, Chapter 70.122, http://apps.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=70.122. Accessed 22 August 2024.

[22] Washington law, for example, allows designated classes of persons to provide informed consent on behalf of an incompetent patient in the following order of priority: 1. guardian with authority to make health care decisions; 2. holder of Durable Power of Attorney with authority to make health care decisions; 3. Spouse or registered domestic partner; 4. adult children; 5. parents; and 6. adult brothers and sisters, followed by several other categories of persons. See Revised Code of Washington § 7.70.065, http://apps.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=7.70.065. Accessed 22 August 2024. If there are two or more persons in the same class listed above (e.g., adult children), then the decision must be unanimous among all available persons in that class.

[23] See III.A.1. above (“Informed Consent”) and accompanying notes.

[24] See, for example, Revised Code of Washington § 7.70.050(4) http://apps.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=7.70.050. Accessed 22 August 2024.

[25] For example, the University of Washington’s policy provides that the definition of emergency “would clearly include treatment that is necessary to preserve life or to prevent serious disability. It also may include other types of treatment that cannot be delayed without risking unacceptable deterioration or aggravation of the patient’s condition.” Informed Consent Manual, UW Medicine, 40 at pp. 22-22 (revision date June 2019).

[26] In Washington State, see Revised Code of Washington, § 26.28.010, https://apps.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=26.28.010 . Accessed 22 August 2024.

[27] See, e.g., in Washington State, Smith v. Seilby, 72 Wn.2d 16, 431 P.2d 719 (1967).

[28] See, e.g., in Washington State, State v. Koome, 84 Wn.2d 901, 530 P.2d 260 (1975); Informed Consent Manual, UW Medicine, 55 at pp. 29-31 (revision date June 2019).