NOTE: The UW Dept. of Bioethics & Humanities is in the process of updating all Ethics in Medicine articles for attentiveness to the issues of equity, diversity, and inclusion. Please check back soon for updates!

NOTE: The UW Dept. of Bioethics & Humanities is in the process of updating all Ethics in Medicine articles for attentiveness to the issues of equity, diversity, and inclusion. Please check back soon for updates!

Author:

Lizbeth A. Adams, PhD, CIP

Related Topics: Informed Consent I Parental Decision Making

Core Clerkship: General Curriculum

Topics addressed:

- What is the definition and scope of CAM?

- How extensively is CAM used?

- What is known about the efficacy of CAM?

- What ethical issues are associated with CAM in clinical practice?

- What ethical issues are associated with research in CAM?

- What are the physician's professional obligations with respect to CAM?

What is the definition and scope of CAM?

The answer to this question continues to invite debate; looking to the federal government for a definition provides at least an historical perspective on the question. In 1991, NIH formed the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM), with funding of $2 million and the directive to “investigate and evaluate promising unconventional medical practices”. At the time, “alternative” simply designated practices considered to be outside of mainstream medicine, or, put another way, practices not commonly taught at conventional medical schools. In 1998 this office was re-named NCCAM, or the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine and in FY 2010 it had a budget of $128.8 million. The addition of the word “complementary” to the title reflected the fact that these practices are increasingly used in conjunction with, and adjunctive to, conventional or “allopathic” medicine. The term “integrative medicine” refers to an approach to patient care that fully utilizes both conventional and alternative methodologies.

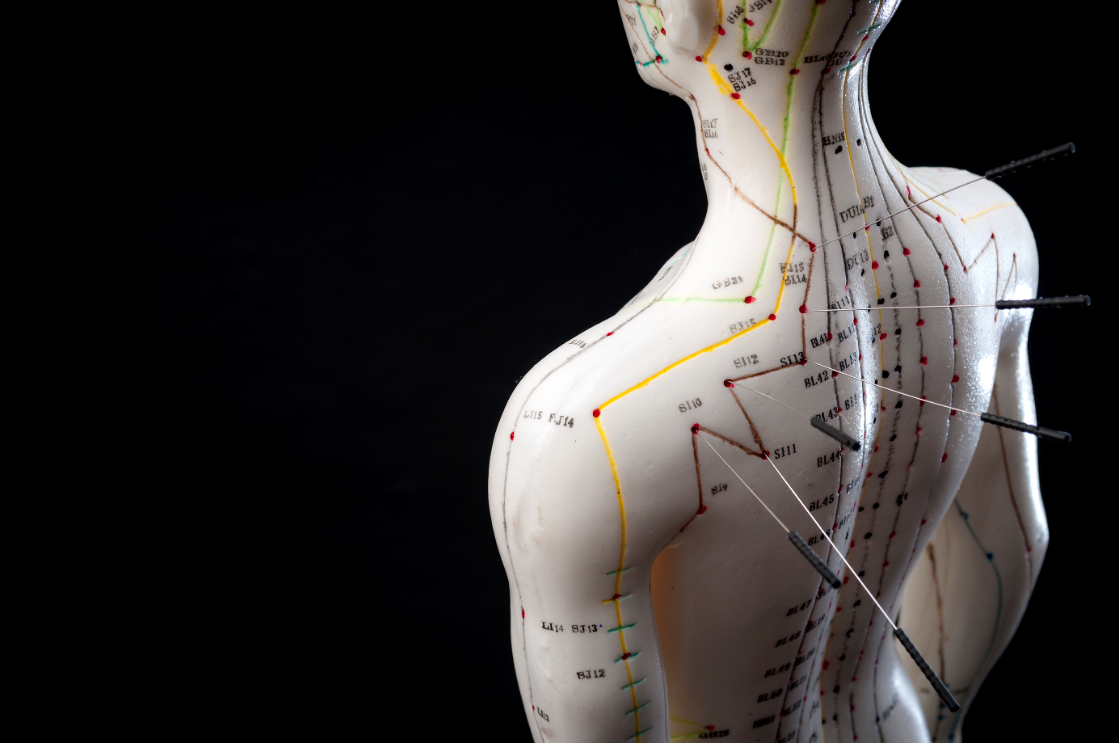

CAM whole medical systems are naturopathic medicine, homeopathy, Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) including acupuncture; these systems have evolved over centuries to millennia. Mind-body medicine and energy medicine encompass a broad spectrum of techniques including meditation, QiGong, and hypnotherapy. Somatic therapies include massage, craniosacral, and chiropractic. This is a fractional list of the many therapies and modalities that may reside under the general rubric of CAM. The NCCAM website is an excellent source of information pertaining to CAM.

How extensively is CAM used?

In 1993, David Eisenberg and colleagues at Harvard University published a systematic survey on the use of “unconventional medicine” in the United States. They determined then that one-third of respondents (study n=1539 adults) used CAM, generally to treat chronic (as opposed to life-threatening) conditions, and the highest use was reported by nonblack persons between 25-49 years of age who were well educated and of a relatively high socioeconomic status. Total expenditures for CAM therapies were $13.7 billion, three quarters of which was paid out of pocket. Subsequent, more exhaustive, surveys demonstrated that CAM use has steadily increased. A follow-up survey by Eisenberg in 1998 and a 2008 report from DHHS place the percentage of adult Americans who use CAM at around 40%, and the percentage of children at 12%. CAM expenditures in 1998 were conservatively estimated at over $21 billion. According to the 2008 report the most commonly used CAM therapies are nonvitamin, nonmineral natural products (for example, herbal products such as Echinacea) and deep breathing/ meditation practices. The most common presenting complaints among people seeking CAM treatment are back pain and other musculoskeletal complaints (National Health Statistics Reports ).

At its founding in 1847, the AMA declared itself and its allopathic members to be sharply opposed to homeopathy, which they later decried as a “cult”. The antipathy of allopaths toward many forms of CAM persisted for much of the 20th century. However in recent decades significant progress has been made in establishing integrative medical centers at which CAM and allopathic practitioners work together to co-manage patients. In the Seattle area each of the major hospitals now includes CAM in their curricula, houses integrated medicine clinics, and engages in collaborative research with CAM researchers. Nationwide, this trend holds also holds.

What is known about the efficacy of CAM?

Research to evaluate the efficacy of CAM is ongoing. Federal funding for CAM research has increased over the past two decades, but still falls short of allocations made to other areas of inquiry. To date, clinical trials have demonstrated some efficacy of CAM therapies in the amelioration of back pain, upper respiratory infections, and diabetes. Medicinal mushrooms are being studied in cancer patients with promising results. In vitro studies provide exciting data on the induction of apoptosis in cancer cells by botanical compounds, modulation of immune function by herbal products or mushrooms, and the mitigation of cellular oxidative stress by botanical extracts. The Cochrane Reviews provide useful summaries of extant CAM clinical trials and all entries articulate the need for more research in the area. There are many methodological issues that make the design of CAM research studies challenging. Following are a few of many examples.

Botanical medicine derives from folk traditions in which plants, either the whole plant or isolated parts of it, are harvested and prepared according to learned wisdom. Botanical extracts are complex mixtures of molecular constituents that are difficult to standardize and characterize, an issue further complicated by the timing of harvest, method of extraction, and growing conditions. The western science paradigm of pharmaceutical development and testing (a single molecule delivered in pure form at relatively high concentrations) does not fit the realities of botanical therapies.

Whole system CAM practices treat the individual patient in a very individualized way, generally using multiple interventions simultaneously. Such an approach does not lend itself to validation by the RCT approach. More appropriate to CAM clinical trials may be the “n-of-1” design. Using this approach, an individual serves as their own control, and the intervention or placebo is each administered multiple times, in random order, with outcome measures taken during each phase. Informative though they can be, these studies are laborious, expensive, and time-consuming for the subject, thus increasing attrition rates.

In designing an RCT, it is often difficult to define an appropriate control group. In acupuncture studies, for example, debate continues about what constitutes sham needling: is it pressure without penetration, or is it needling at a point known to be ineffective, or is it a time and attention control? In botanical medicine studies on compounds with a strong or recognizable taste (for example, garlic), how does one come up with true placebo?

NCCAM addresses some of these concerns in its current statement of funding priorities , asserting the need for pharmacokinetic studies of biologically based interventions, the optimization of dosing regimens (across modalities) and control groups, and the refinement and validation of outcome measures. Additionally, studies on safety and efficacy and mechanistic studies are being encouraged.

What ethical issues are associated with CAM in clinical practice?

In the context of clinical practice, the ethical issues pertain to providing optimal medical care to an individual. Any physician, allopathic or otherwise, is bound by oath to do no harm and to provide the most efficacious therapies to their patient. The precepts of evidence-based medicine (EBM) and the accessibility of medical research literature provide clinicians with powerful tools to identify such therapies. In evaluating the risk of harm and the potential benefits of any therapy, weight must be given to the amount and quality of research that has been done on the intervention, known risks and side effects of the therapy, the credential and competence of the practitioner, the seriousness of the condition being treated, and the belief system and wishes of the patient. Given the relative dearth of research literature on many CAM therapies, the clinician must use best judgment to decide which therapies are unlikely to do harm, either directly or by reducing the effectiveness of other therapies, and which may offer some, if not great, benefit. A CAM therapy that is neither harmful nor effective can become damaging if it precludes the patient obtaining effective treatment.

The advantage of integrative medical clinics is to take much of the guesswork out of this algorithm. Well-trained, licensed CAM providers working alongside conventional clinicians create an environment in which patient care can utilize current best practices in each discipline. CAM therapies for some medical conditions require close supervision by a CAM professional. Just as a patient with diabetes (or hypertension, depression, etc) should receive ongoing medical supervision for his/her diabetes (hypertension, depression, etc) management, the same holds for CAM therapies. Many warnings about the risks associated with CAM therapy use are grounded in an assumption that the patient may be self-treating and/or not receive adequate monitoring by a trained CAM professional.

What ethical issues are associated with research in CAM?

In the context of CAM research, different ethical issues arise. The following is a small sampling:

- Informed consent: The regulations stipulate that the informed consent document and process must accurately describe reasonably anticipated risks and potential benefits. Yet in many instances CAM therapies have not had systematic safety or efficacy data collected, and are ratified by historical anecdotal evidence. The informed consent document should state that although a therapy might have been in widespread use, rigorous safety data may not be available.

- Misconceptions: A prospective research subject must weigh for themselves the balance of risks and benefits that will accrue from their participation. The therapeutic misconception is the (documented) belief held by many research subjects that they will benefit from participating in a research study (allopathic or CAM), irrespective of disclaiming language in the informed consent form. This misconception weighs in favor of participation. Additionally, there is a widely held notion that if something is “natural” it must be safe, or beneficial. This misconception also weighs in favor of participation by reducing the perceived risks associated with the study. In CAM research it is imperative to impress upon potential subjects that the risks and benefits of participation are more difficult to anticipate than they are for better-studied interventions.

- Study design: The Belmont principle of beneficence dictates that there be a reasonable likelihood of obtaining useful data from a study. As discussed above, the difficulties inherent in generating sound designs in CAM research challenge adherence to this principle. Research study designs must undergo rigorous review by scientists and clinicians well versed in the CAM modality being tested.

What are the physician's professional obligations with respect to CAM?

Given the number of Americans who use CAM in combination with allopathic medicine, the issue of interactions between therapies is a pressing one, particularly in the case of botanical compounds. The demonstration that garlic, used therapeutically in AIDS patients in the 1990s, interfered with the activity of HAART drugs provided a sobering reminder that herb-drug interactions should be studied as rigorously as drug-drug interactions. This is also an example of an “herb” also being a “food”. The dose may be all that separates medicinal from food use, with potentially large ramifications, thus it is important to know more about food/nutrient-drug interactions. For the allopathic clinician, it is especially important to track the patient’s use of all CAM therapies. Offhand dismissal or ridicule of CAM will impair communication and the therapeutic relationship with the patient; harmful herb-drug interactions could be missed or the patient may break entirely with the allopathic system.

The CAM physician has obligations to adhere to the best practices of EBM, understanding that research in CAM lags practice. There is a danger for clinicians as well as for patients to believe the “if natural, then safe” fallacy, and there is danger in the tendency, however innocently formed, to use natural products as pharmaceuticals. The emerging Vitamin D story illustrates that overprescribing or overdosing a “natural” compound can have unintended negative consequences.

CAM therapies provide useful tools to improve human health. As CAM research proceeds, the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of individual therapies will be established, and the effective CAM therapies will add significantly to the armamentarium of modern medicine. As concerns about the costs of health care grow, it will be particularly important to perform cost-benefit analyses on CAM therapies and determine whether they, used in informed combination with conventional care, might serve to reduce the economic burden of our national health care.