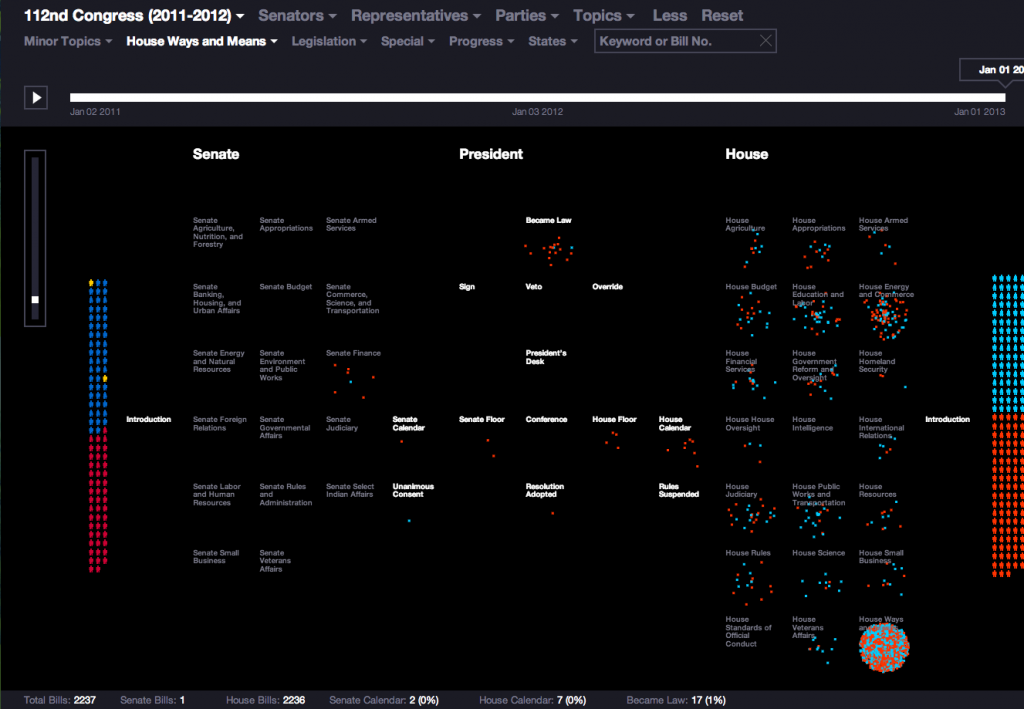

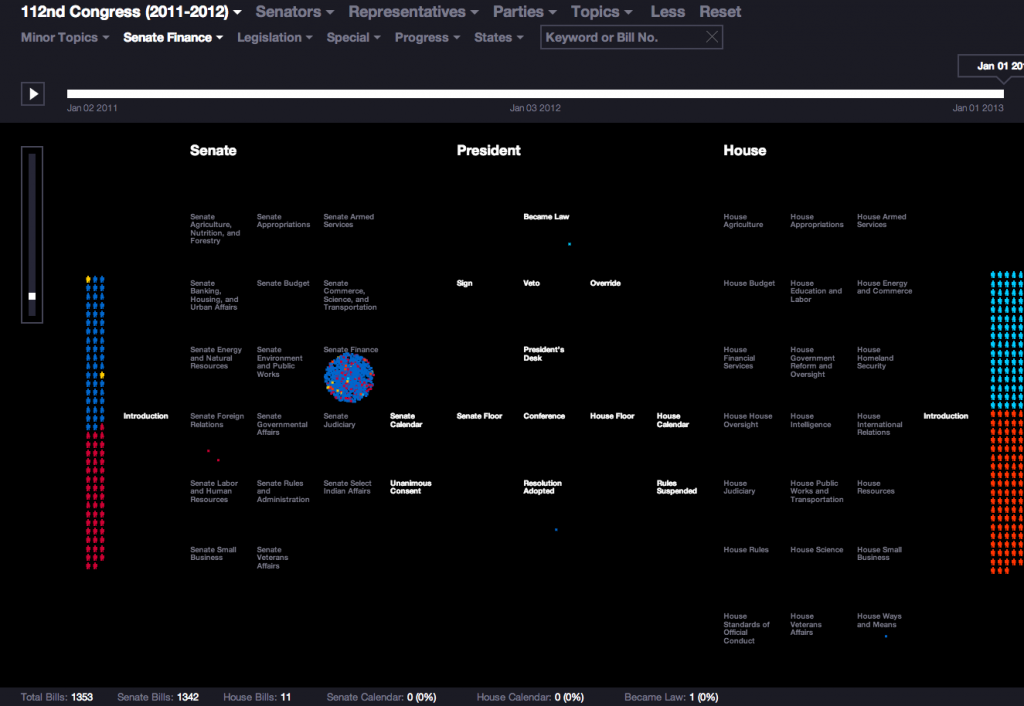

Another perspective is to limit attention to bills referred to a particular committee or committees (using available filters). This helps to underscore how the progress of bills often has little to do with a sponsor’s efforts and abilities. Compare, for example, the progress of bills referred to the two tax committees (below).

In the House, referring bills to multiple committees at once is a fairly common practice, giving the Ways and Means committee broad influence because so many bills have revenue implications. The Senate process is strikingly different. There is no multiple referral in the Senate so the Finance committee does not have jurisdiction over bills referred to other committees.

But the most striking differences are the success rates for bills referred to these two committees. Only one bill under the jurisdiction of the Senate Finance committee became law (The Protect our Kids Act of 2012), compared to 17 bills in key areas such as free trade, tax relief, and more, for House Ways and Means.

Why was the Republican-controlled House seemingly so much more influential in this issue area when the Senate was controlled by the same party as the presidency? The answer is rooted in the Constitution, which specifies that “All Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives.” Senate sponsors are doomed to failure where bills that involve raising revenue are concerned (a substantial proportion of all important legislation, including the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act).

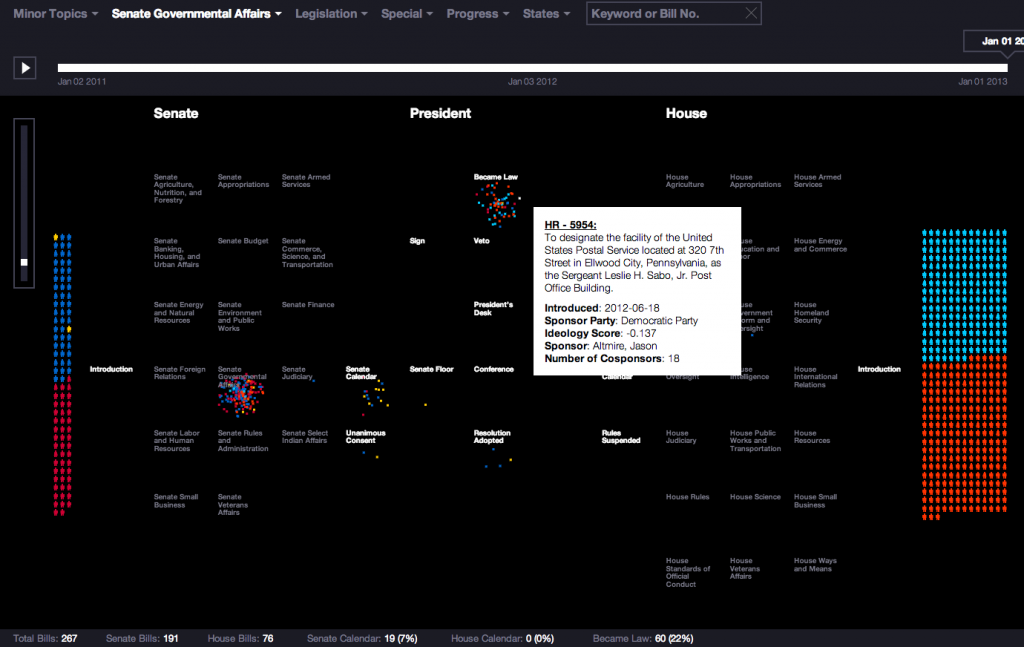

Another perspective is to examine committee success rates. Which committee’s bills were most likely to become law? Of the 284 bills that became law in the 112th Congress, sixty fell under the jurisdiction of the Senate Governmental Affairs committee. This committee’s bills has an impressive 22% success rate compared to an overall success rate of just 2%. However, clicking on some of these bills reveals a pattern that is less impressive. Most of these laws named federal buildings, while the remainder were specific to the federal government’s District of Columbia oversight responsibilities.