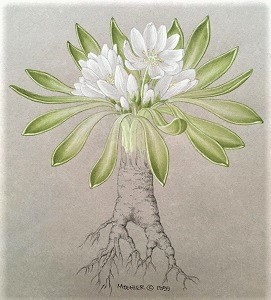

Micheal Moshier's family has generously donated his original artwork for LeRoy Davidson's 2000 monograph

Lewisias to the Miller Library, and we are so excited to feature these plant portraits in our exhibit space this month. In the words of donor Jeff Uebel:

My uncle, Micheal Moshier, was a talented, prolific landscape and plant artist and a skilled, dedicated landscape designer and craftsman. He traveled and worked all along the West Coast and Hawaii, but his home base was the Puget Sound, especially right here in and around Seattle's Washington Park Arboretum. He is probably best known for his incredibly detailed pen, ink and graphite depictions of sun and cloud-drenched Cascade and Olympic peaks and waterfalls, rocky outcrops and islands in the Puget Sound, and placid scenes along Lake Washington. He was equally fascinated by and recorded the tiny components of these areas: mushrooms, flowers, leaves, kelp and stones.

He was particularly proud of his work with LeRoy Davidson to create the monograph Lewisias

and asked that his illustrations for that work be kept together, to be shared and enjoyed by as many people as possible. We hope that you do enjoy them.