Eccentrics have been described as having “varieties of physical and behavioural abnormality that occupied ‘contested space at the juncture of madness and sanity’” (pp. 1-2). In

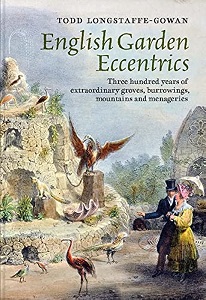

English Garden Eccentrics: Three Hundred Years of Extraordinary Groves, Burrowings, Mountains and Menageries Todd Longstaffe-Gowan shows how a group of English men and women in the seventeenth to twentieth centuries used their gardens to express and develop their eccentricities. That means, of course, that in addition to describing their wonderfully diverse gardens, he also tells us many juicy bits about the gardeners’ lives.

It's worth noting that “garden” in this case involves many things in addition to plants, and sometimes not many plants at all. The book presents twenty-one of these oddities, each with excellent illustrations: drawings, paintings, woodcuts, photographs – all very worth examining.

At Hoole House in Cheshire the focus falls on the garden itself more than the owner, Lady Broughton. She had come to Hoole House after she separated from her husband, Sir John Delves Broughton, 7th Baronet, in 1814. (Titles abound among these gardeners.) Separating from your husband and setting up your own household was eccentricity enough.

After her arrival, Lady Broughton had constructed a large and very tall rock garden covered with alpine plants and laid out to resemble shapes of the Swiss mountains at Chamonix, including the glacier at their base. A contemporary illustration from Gardener’s Magazine is paired in the book with a pen and ink drawing of the mountains to make clear how exactly the garden rocks matched the outline of the mountains. That the garden’s representation of the glacier made the area feel cool even in summer, as one visitor insisted, readers can only imagine.

One garden with a primary focus on plants was Viscount Petersham’s in Derbyshire. Petersham, a companion of the Prince Regent who became George IV, was described in 1821 as “’the maddest of all the mad Englishmen’” (p. 83). After he married a beautiful but scandalous actress, he developed his garden to entertain her – in the country, far from public view. A central project of this new garden became the transplanting of topiaries and other trees. William Barron, Petersham’s Scottish gardener, learned how to transplant mature trees successfully, and by 1850 had moved hundreds onto the property. “It was as though the earl were devising every form of horticultural diversion possible to keep his wife from pining for an existence beyond the bounds of her prison paradise” (p. 87).

The illustrations show that at least some of his many topiaries had shapes much more varied and complex than the more typical birds. Yews shaped like enormous mushrooms, tall columns, even a cave-like arbor were enclosed in a long, undulating hedge. One visitor responded enthusiastically to the prospect, reporting: “’we actually threw our body down upon the soft lawn in an ecstasy of delight’” (p. 96).

In one final glimpse of another garden, Lamport Hall

exhibited the now ubiquitous garden gnome gone mad: Many dozen tiny ceramic gnomes were scattered throughout.

Well researched and lavishly illustrated,

English Garden Eccentrics yields both copious information and a great deal of entertainment.