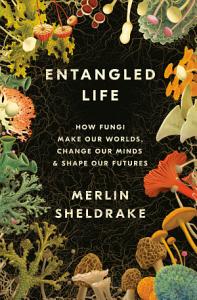

Only a few pages into Merlin Sheldrake’s

Entangled Life, my mind expanded like a puffball, fit to burst from the wildly proliferating spores of ideas. This is so much more than a book about mushrooms, the showy fruiting bodies that tend to dominate our attention to the fungal world. Merlin Sheldrake, son of biologist Rupert Sheldrake, holds a Ph.D. in tropical ecology for research on mycorrhizal relationships. The book should appeal to scientist and layperson alike, as the author excels at communicating complex concepts in lucid and literary prose, while retaining a sense of humor, wonder, and above all, hope. What role does hope play? Reading the book at this time of pandemic and social inequity, the notions of mutualism, symbiosis, and involution (involution — distinct from evolution's focus on competition

— attends to patterns and strategies of cooperation) ramify beyond the realm of mycelial networks, their implications readily extendable to human interaction.

...[Editor's note: this is an excerpt. Read Rebecca's entire review in the Gardening Answers Knowledgebase.]...

The book calls attention to the groundbreaking research of scientists, many of them women (Suzanne Simard's work on carbon transfer between plants; Katie Field on mycorrhizal solutions to agricultural problems; Lynne Boddy on mycelial networks; Lynn Margulis's endosymbiotic theory once dismissed as "evolutionary speculation"). Sheldrake describes his meetings with Pacific Northwest innovator and fungal theorist Paul Stamets (who has recently been working on fungal antiviral compounds), and mycoenthusiasts and entrepreneurs like Peter McCoy (founder of Radical Mycology, a group that promotes citizen scientist education on things fungal, such as mycoremediation and mycofiltration). Farther afield, in New York, the versatility of fungi is being harnessed to make biodegradable packing and building materials and furnishings as alternatives to plastic. Imagine ordering a grow-your-own-lampshade kit, or sitting on a fungal stool!

Each chapter presents surprising observations that may dismantle and rearrange the reader's preconceptions. We humans tend to think of ourselves as discrete, separate individuals, but each of us is actually an ecosystem "composed of — and decomposed by — an ecology of microbes" that make it possible for us to function (to digest our food and reap nutrients from it, for example). We are not unique in this. Symbiosis is widespread.

...[Editor's note: this book is available as an ebook or downloadable audiobook from Seattle Public Library. King County Library System patrons can request access to a downloadable audiobook edition.]...

This book is the work of an adult who has retained his childhood curiosity about the world, who built piles of leaves and embedded himself in them to see if he could experience their decomposition. He continues to be a fungal experimenter, brewing and fermenting, and exploring the many possibilities of partnering with fungi to mend the planet. I highly recommend immersing yourself in this book. Merlin Sheldrake's enthusiasm is contagious.