The stiff spikes of gladioli are a mainstay for florists and favored by home gardeners for the hundreds of named cultivars in almost every color. Lesser known is the large genus of

Gladiolus in the Iridaceae family with about 300 species, thriving in a wide range of environmental settings.

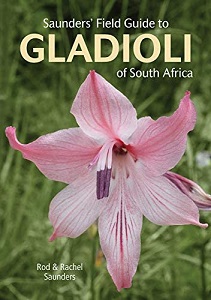

While there are a handful of Eurasian species near the Mediterranean, and others that can be found in tropical Africa, the concentration of this genus is in South Africa. An extensive (almost 400 pages) new field guide,

Saunders’ Field Guide to Gladioli of South Africa is remarkable in being focused on this single genus.

While a few of these species are of horticultural interest and will grow with care in our climate, I think the main attraction of this book is the breadth of variety in a flower that is very commonplace in horticulture, but otherwise not well known. For example, I am struck by how many of the species are scented, a trait unknown in cultivated glads.

The authors,

Rod and

Rachel Saunders, were killed near the end of their efforts to photograph all the native species of their country in flower, leaving Fiona Ross to complete the book with the help of many others. While a must for a botanically inclined visitor to South Africa, this field guide is fascinating just for its level of detail and the diverse beauty of its subjects.

An example is

G. cardinalis that grows in the province of Western Cape. “The plants flower in midsummer, the driest time of the year. The corms are wedged into cracks in the rocks where they are protected. Corms and roots must be constantly wet, and have been found in very fast-flowing river…often found flowering together with

Disa uniflora, an orchid of a similar colour; the two species share the same pollinator.”

Eight different photos accompany this description, showing the bright red flowers cascading off of a wet cliff wall. Surprisingly, regional nursery

Far Reaches Farm carries this species, having found it to be hardy and amenable to garden culture. I’m eager to give it a try.