|

|

|

|

The Power of an Emperor: The Augustinian Agenda & Imagery As Propaganda |

|

written

by odis / 09.08.2004 |

|

|

| |

Rise to Power |

| |

| |

|

| http://utenti.romascuola.net/bramarte/greci/img/scu2.jpg |

| Apollo |

| The famous Roman statue, "Apollo Belvedere", of the Greek god Apollo. |

| |

|

| |

|

| http://www.controverscial.com/Greek%20Mythology.htm |

| Dionysus |

| A Roman statue of Dionysus portrays him drinking wine. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

| Denarius of Octavian |

| A coin that shows Octavian facing Caesar, with the faint words "Divi Filius" emphasizing Octavian's divinity as a product of his relation to the former ruler. 38 B.C. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

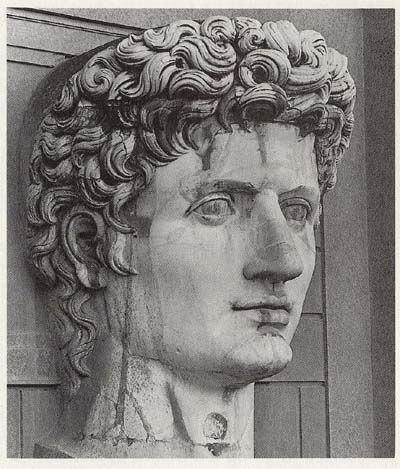

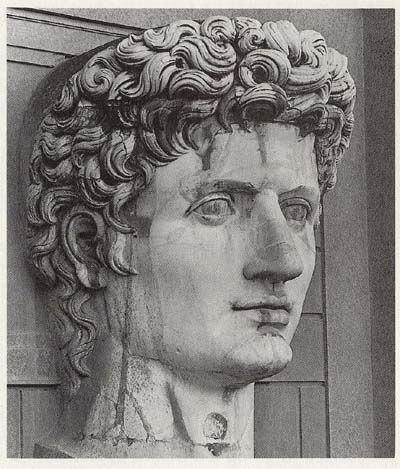

| Militaristic Octavian |

| This statue demonstrates the youthfulness and arrogance that defined Octavian's earliest portrait type. Includes Baroque modifications to the hair. 33 B.C. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

| Equestrian Monument |

| This coin depicts the equestrian monument voted by the Senate in Octavian's honor in 43 B.C. When such a statue could not be put up around the empire, its image was frequently distributed on coins. Octavian is riding on a galloping horse with a naked torso. This coin again displays the "Divi Filius" title that Octavian gave himself. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

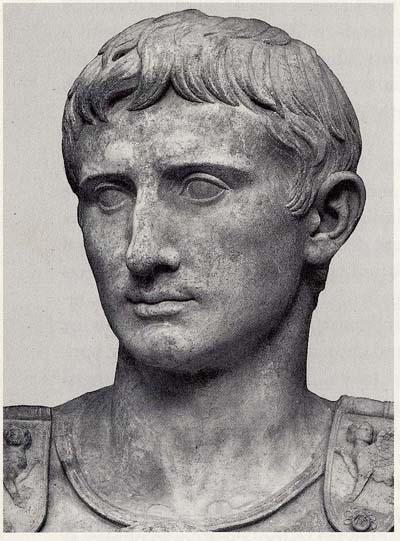

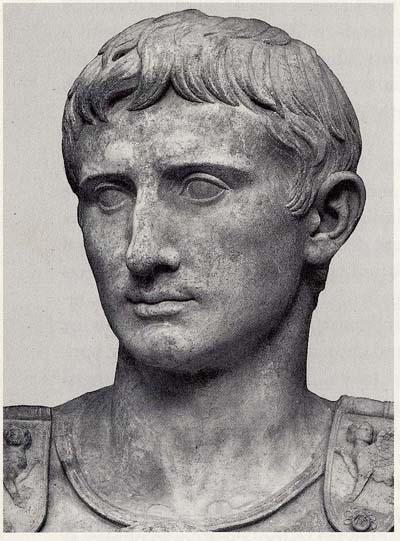

| A New Image |

| The portrait that has primarily represented Augustus throughout history, despite its few actual physical traits of him. 27 B.C. |

| |

|

In the scope of the Roman Empire’s history, perhaps no emperor is as lauded as Augustus. Born under the name Gaius Octavius, he seized sole power in 31 B.C. and, through a dramatic program of cultural reformation, moved Rome into an era commonly referred to as the “Pax Romana”, translated from Latin as the “Roman Peace”. In the years before his rule, the empire had been mired by what many in the leading class considered to be a degradation of values and a focus away from the Roman religion that had so definitively been a part of the empire’s rise. In addition, political discord had resulted in a century of civil war. To combat this chaos, Augustus’ agenda encompassed three areas of improvement: 1) an increased focus on the integration of religion into public life, 2) the construction of magnificent public monuments and buildings, and 3) a revival of moral virtues. By the time of his death in 14 C.E., the Roman Empire was well into an unprecedented two hundred year period of peace and prosperity.

The beginning of Octavian’s rise to power has its roots in the period immediately following the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C. As Caesar’s great nephew, adopted son, and chosen heir, Octavian, only nineteen years old, united with Mark Antony and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus to form the second triumvirate and force the Senate to allow them consular power. They initially divided control so that Octavian had rule over Spain and Sardinia, Antony the East and Gaul, and Lepidus Africa. When Antony’s lieutenant died in 40, however, Octavian used the opportunity to take Gaul, and by 36, he had replaced Lepidus in the South.

This increase in power left Octavian with only Antony in the way of his rise to the role as Rome’s lone ruler. The strain that would have certainly been a product of sharing power in the world’s largest republic had undoubtedly magnified, and Antony’s decision to take up Cleopatra, the Queen of Egypt, as his lover- despite having married Octavian’s sister in 37- could only have aggravated the relationship. Cleopatra was the mother of Caesarion, whom she had by Julius Caesar, and believed him to be Caesar’s true heir. By 32 B.C., Octavian and Antony were engaged in civil war.

IMAGERY AS POLITICAL PROPAGANDA

Beyond the massive military forces that Octavian claimed leadership over, perhaps the most powerful tool that he used in the conflict with Antony was the manner in which he portrayed both himself and his opponent. If he were to gain the necessary backing to engage in civil war, after all, he would need to demonstrate his own superior ability over that of Antony’s. A significant element of his winning power, then, had to do with convincing Rome that he would be the best ruler.

Long before the conflict with Antony had even begun to move toward war, Octavian had been creating himself an image that would fit well with his intention to rule. It was a frequent occurrence for Roman leaders to relate their ancestry to Greek gods and the decisions of Octavian and Antony were no exception. Octavian chose Apollo and Antony Dionysis. The difference in such a choice could not have been more significant; Apollo’s image was that of discipline, morality, purification, and punishment for excess, while Dionysis was a passionate lover of wine, parties, and affairs. For an empire that had endured decades of civil war and drastic leadership change, the image of Dionysis as ruler was not likely to be endearing.

Perhaps more important than his association with Apollo was Octavian’s relationship to Julius Caesar, which, from the moment he became part of the triumvirate, he emphasized often. In 42 B.C. he obtained admission from the Senate for Caesar to be deified, meaning that, as his son, Octavian became the “Divi Filius”, the son of a god. In stressing this connection to Caesar, he was thus emphasizing his own divinity. This reference was most obvious on the coins Augustus minted; frequent images included Caesar’s throne or Octavian’s profile facing Caesar’s. One particular coin portrayed Aeneas and Venus, a reference to the divine ancestry that Caesar, in his lifetime, had claimed for himself. In borrowing these images, Octavian was claiming a direct relation to the divinity of the Julian family.

Another important tool that was important in shaping the Roman public’s perception of Octavian during this period- and one that he would use throughout his rule- was his image as it appeared on the empire’s statues. He was youthful and beardless (an extremely atypical image for a male leader of this period), and his expression is regularly defined as arrogant. His hair is dishevelled, an element that, in combination with the other features, certainly evokes Alexander the Great and his miraculous campaigns. One of the first and most fantastic of Octavian’s statues, put up in 43 when he was only nineteen, is that of him on a galloping horse placed in the Senate chambers. All of this imagery serves to portray Octavian as strong and capable of commanding not only an army, but also the entire empire. In combination with the emphasis on his own divinity, Octavian played off the concerns of Rome’s citizens and provided a stark contrast to the decadence and drunkenness of the Dionysian Antony.

In 31 B.C., at the Battle of Actium, Octavian defeated the forces of Antony and Cleopatra and thus ended the civil war. From this date until 23 he had himself elected consul, marking the beginning of his rule. In 27 B.C. the Senate assigned him “maius imperium”- greatest power. This is generally seen as the date in which the empire was consolidated and Octavian became Rome’s first emperor, or “Imperator Augustus”. This new title was given to him by the Senate and carried with it significant religious (an “augur” was a priest who interpreted omens) and political implications. Though he is frequently characterized as having returned Rome to its people, no previous Roman leader had ever been allowed as much power. Augustus slyly self-designated himself the “princeps”, or “first citizen”, and primarily relied on this title rather than “Imperator”, a move that would parallel the modesty with which he chose to rule.

Along with this change in title came a modification in image. The statues that were being built retained Augustus’ beardlessness and youth, but no longer kept his arrogance, instead focusing on proportionality and beauty. His hair, for example, no longer had the wild locks that reflected Alexander the Great, but was neatly divided into (unrealistic) symmetrical sections. Overall, these statues had very few of the actual physical traits of Augustus. Regardless, writers of his time, undoubtedly influenced by these portraits, described him with words like “gravitas”, “sanctus” and “auctoritas”, respectively meaning dignity, holiness, and authority. Throughout history these statues have been the predominant representation of his appearance, and the notions that they associate with Augustus would come to define how history perceived his reign.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|