|

|

|

|

The Power of an Emperor: The Augustinian Agenda & Imagery As Propaganda |

|

written

by odis / 09.08.2004 |

|

|

|

Augustinian Agenda |

| |

Religious Renewal |

| |

| |

|

| http://www.vroma.org/images/mcmanus_images/augustuspontifex.jpg |

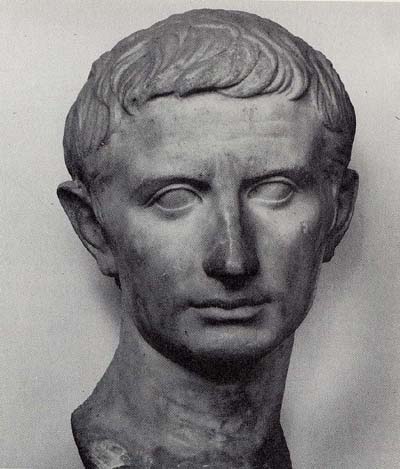

| Pontifex Maximus |

| Last decade of 1st Century B.C. |

| |

|

When Augustus inherited Rome, public sentiment was pessimistic. The decades of civil war that had preceded (and occurred during) his rise to power were seen as an indication of the empire’s moral collapse. To combat the disorder and mistrust that had afflicted Rome, Augustus would have to engage in an astounding program of national revitalization and, in so doing, make such a program visually evident to Rome’s masses. In the twenty years following his designation as emperor, Augustus literally changed the Roman landscape with his plan to conspicuously revive its society. The primary themes included revitalization of religion, virtues, and the honor of the Roman people.

Augustus’ program for religious renewal began around 29 B.C. The most comprehensive of his promises include the following: to rebuild all of Rome’s ruined temples; to reinstitute many cults, allowing the revival of their statues and rituals; to bring back the Roman religion’s former priesthood; and to emphasize that the religion’s texts should regain authority as guides to behaviour. In 28, he finished and dedicated the Temple of Apollo, a ceremony that was indicative of his dramatic change in focus regarding the primary gods of Rome’s religion. At the expense of Jupiter’s responsibilities, this new temple gained the Sibylline books. (These texts were oracular scrolls written by prophetic priestesses). In addition, Mars Ultor, the god of war, gained the ceremonies that preceded and followed military campaigns, another of Jupiter’s former associations. The only religions that were discouraged in this new era were those rooted in the cultures of Egypt and the Far East. Because these cults promoted salvation to people as private individuals they threatened the principals of the Roman religion, carrying with them the danger of alienation from the larger society and the creation of private, dissolute sects. Despite this particular discouragement, Augustus was successful at using the formation of most cults to create a link between the ruling class and the plebeians; whenever a group of Romans got together to begin a cult, the princeps was more than willing to donate a statue for them. In this way, religion became a tool for the apparent minimization of class difference.

For members of the Roman priesthood, the Augustan agenda did not affect their social status so much as it did their powers. Their responsibility to interpret bad omens was eliminated, the Sibylline books were well hidden under the Temple of Apollo, and Augustus gave himself the responsibility of carrying the augur’s staff prior to military campaigns. These changes were all an indication of the princeps’ agenda to increase his own religious responsibility. In 12 B.C., when Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, the Pontifex Maximus (chief priest), had passed away, Augustus assumed the position for himself, merging the powers of church and state under one title and becoming the mediator between men and the gods.

This transformation was hardly a radical one, however. Imagery from essentially 20 B.C. on depicted Augustus as highly pious. He was frequently clad in a toga and his facial expression evokes a modesty that is a far cry from the arrogance and wild hair that was a staple of his image during his rise to power. The abundance of these statues, exhibited as far away as Greece and Asia Minor, is not only an indication that he considered this position one of great honor, but that he was a model of piety for all Romans to follow. This notion is manifested in his encouragement for all citizens to wear the toga at festivals and in public places, despite the garment’s relative unpopularity.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Ambitious Public Building Program |

| |

| |

|

|

| Enclosure Wall of the Forum of Augustus |

|

| |

|

Augustus’ building program was far-reaching and grandiose. Prior to his reign, in the late Republican society, the appearance of the state’s public buildings was poor relative to those of wealthy private individuals. Though Augustus himself and many of his primary supporters, had amassed immense fortunes during his climb to power, he decried private luxury and extensively invested his government in restoring honor to the empire and its people by putting up elaborate public buildings and monuments.

This program went forth even at the expense of private wealth. One famous and symbolic gesture occurred when Vedius Pollio, a very rich freedman known for cruelty to his slaves, gave Augustus his estate when he passed away. The princeps levelled Pollio’s mansion and, in its place, built the Porticus Liviae, opening it to the public and filling it with fountains, colonnades, and art.

For secular projects such as this, Augustus primarily relied on the engineering of Marcus Agrippa, one of his closest friends and the commander of his military campaigns. Agrippa was responsible for a wide range of Rome’s engineering marvels during this period, some of the most well known including the complete reorganization of the empire’s water supply, involving the reparation and building of new aqueducts and the building of the first public baths. He was also responsible for the construction of Campus Agrippae, which included a racetrack for horses, an exercise area, and the extensive incorporation of Greek art. He assembled the largest sundial ever- the Solarium Augusti- using an Egyptian obelisk, restored the Theater of Pompey and built two new theaters, all of which, when used together, had a total capacity of 40,000. The greatest of Agrippa’s expansions involved the Saepta Iulia, a voting place for the plebs and a testament to Augustus’ incorporation of lower class involvement.

Another significant indication of Augustus’ commitment to the lower classes were the seventy days a year given to using the afore-mentioned theaters, and often the Saepta Iulia, for regularly scheduled sporting events. The writer Suetonius declared that Augustus “surpassed all his predecessors in the number, variety, and splendour of his games” and Augustus himself declared that he gave gladiatorial games eight times, with the use of ten thousand fighters, and animal games twenty-six times, with a total of thirty-five thousand animals killed. Augustus was also renowned for the frequency and enthusiasm with which he attended the games. Unlike many other government officials, he was unconcerned the prospect of sitting with the masses, and the applause he received was a strong indication of his popularity and power. His genuine interest in the activities and his practice of apologizing when he was unable to attend gratified the citizen attendees; previous leaders had rarely expressed such enthusiasm.

Relative to the emperors that followed Augustus, however, his zeal for sporting events was easily outdone. It was not until Vespasian that the Colosseum was built and such entertainment could be performed on a much more massive scale. In general, Augustus’ focus was theater; Roman poets, particularly Horace, Ovid, Livy, and Vergil, flourished in the Augustan age, and their plays were performed in the public theaters. If Rome was to be the cultural center of the Empire, it would need to outdo the productions of the Greeks.

Another important symbolic structure that signified the magnificence of Augustus’ building program was the wall that surrounded the Forum of Augustus. Perhaps the most interesting elements of this construction were its course and its function. Augustus was unusually careful in making certain that its route did not touch private property, another example of how the princeps demonstrated that he, too, was subject to the laws of the Empire, just as other citizens were. Its primary purpose was to serve as a dividing line between the simplicity of residential areas and the magnificence of the newly erected public buildings and temples. In isolating his new architecture in such a way, Augustus further highlighted its magnificence, keeping in theme with his famous statement that he “found Rome brick and left it marble”.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Return to Morality |

| |

| |

|

|

| Ara Pacis Augustae |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

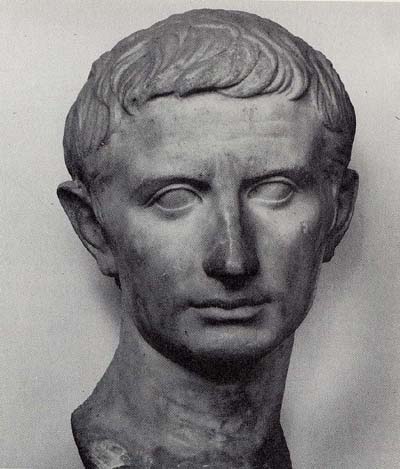

| An Older Augustus |

| As the princeps aged his portrait remained ageless, but the hair gains a more realistic appearance and all traces of the youthful hero are gone. |

| |

|

Augustus’ yearning for a revival of moral virtues was not out of place when he assumed the emperorship; as previously mentioned, immorality was largely perceived to be the cause of the extensive political disorder that plagued the previous years. Unlike his other reforms, however, this one proved most difficult to legislate, and little of its effects are evidenced in the art or architecture that remains.

One of his more ambitious attempts at moral legislation was the product of his desire to improve Rome’s sexual ethics and get the upper classes to produce more children. In 18 B.C., he made it possible for adulterers to be criminally prosecuted, for penalties regarding inheritance to be carried out against unmarried persons, and for rewards to be given to parents who produced many children. The visual expression of these ideals is limited, however. The focus on the significance of offspring could be interpreted to be expressed on the Ara Pacis Augustae, an altar honoring Augustus erected by the Senate for his successful military campaigns in Spain and Gaul, where the imperial children take up the forefront of the imagery. This positioning, however, could simply be explained as the natural location for children to be placed on such a monument. It is known, however, that a statue was built in honor of an especially fertile slave woman, and that an old man who had produced sixty-one descendants was received at the Capitol and made a sacrifice. The frequency of such events is unknown, but is unlikely to have been too significant. Ultimately, this program was considered a failure; the upper classes, to which it was principally directed, thought it was foolish and meddled too much in the private lives of Rome’s citizenry.

Despite the legislative shortcomings of this agenda, Augustus’ greatest influence on Rome’s morality may have come from his decision to (relatively) downplay his own significance. He had continually attempted to lead by example, and eventually his image became significantly more simple and modest. As previously mentioned, generally all monuments built in his honor took on religious connotations. Many of the altars erected for him were of relatively modest proportions; the Ara Pacis Augustae and Ara Fortunae Reducis do not seem to fit with the image of the “divi filius” that Augustus had so insistently focused on in the 30s B.C. His constraint is also evident in his decision to allow other men to build in a period when construction was such a prominent aspect of his program. Balbus the Younger was allowed to build a theater in celebration of a triumph, and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, with financial assistance from Augustus, restored the Basilica of the Aemilii in the Forum.

Around 17 B.C. a new portrait of Augustus emerged, displaying this humility. In relation to the statues of 27 it displays a greater proportion of his actual physical traits, abandoning the forks and tongs of the hair and the youthful arrogance of the face. Regardless of this creation, the previous, more youthful-looking portrait remained the standard, and still today is seen as the primary representation of Augustus’ image.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|