Communist-led Unemployed Council demonstration at Tacoma City Hall, 1931 (courtesy of Tacoma Public Library).

If ever

a political credo was vindicated by wider events, the stock market crash

of October 1929 reinforced the CP USA’s goal to overturn the

capitalist system. The

Crash personified capitalism at its most obvious failing, and was, as

well, Communism’s greatest chance to establish the case for a Marxist,

worker-based economy and political system. By raising the political consciousness of the disaffected and

poverty-stricken unemployed, the Communists could foment the

revolutionary overthrow of the capitalistic system. Or could they? Could

Washington State, which had a relatively small population with a high

degree of industrialization, be the place to instigate change?

With its dependence on resource extraction, Washington experienced slowdowns when domestic and foreign export markets declined. By 1930, lumber production in Western Washington fell by more than 25% and coal mining declined by almost 12%. In the farming-dependent counties of Eastern Washington, wheat-price declines were matched by the falls in production and export. Unemployment grew steadily. There are no adequate statistics but commentators estimated that there were between 40,000 and 55,000 out of work in Seattle by the spring of 1932 or at least 25 percent of the workforce. Unemployment was just as common in other cities and in the lumber areas of the state.[i]

The response to the Depression from organized labor in Washington was initially muted. Workers in industries or firms not organized were among the first to lose their jobs but the cuts soon fell across all employment sectors. The first response from the leadership of the Washington State Federation of Labor was to blame immigration for rising joblessness. However, by the time of the Federation’s annual convention in June, 1930, the organization had begun to see that the problems of unemployment, including financial help for the jobless and their families, were important topics deserving attention. Even so, labor leaders were ill equipped to tackle the issue. American Federation of Labor (AFL) unions in Washington had long regarded it an employer’s responsibility to provide relief to unemployed workers; unions tended to focus narrowly on safety, wages and workplace conditions rather than on the broader issues of social and economic conditions

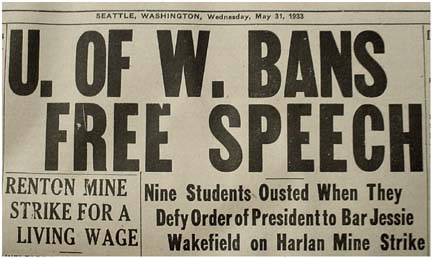

When YCL members defy UW authorities and invite a Party leader to speak on campus they were eventually expelled. Voice of Action 5/31/33

Of

course, Communists were not encumbered by a faith in any part of the

existing economic system. After

years of trying to organize inside AFL unions ("boring from

within"), the Comintern in 1928 had developed a new policy of building party-controlled unions. The Trade Union

Unity League would be the Communist alternative to the AFL. When the

Depression hit, the Party also developed an organizing strategy aimed at

the unemployed. As part of a 13-point list of demands — which included

unemployment insurance equal to full wages, a seven-hour day and

recognition of the Soviet Union — the Communist Party called for the

formation of Unemployed Councils. Every local and district office of the

Trade Union Unity League was told to set up a council and instructions

on how:

Into these

Councils shall be drawn representatives of the revolutionary unions,

shop committees and reformist unions, as well as unorganized workers.

The councils shall be definitely affiliated to the respective TUUL.[ii]

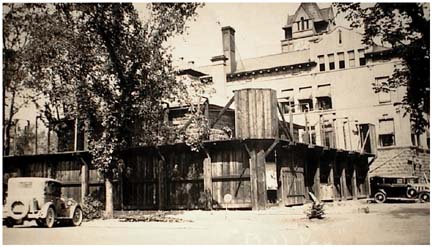

When the IWW led a strike of hop pickers in Yakima in 1933 they were herded into this makeshift prison. Communist organizers were soon to join them. MSCUA, University of Washington Libraries, UW 2400In

cities like New York, Chicago, and Detroit, the Unemployed Councils made

an immediate impact, staging large attention- getting demonstrations in

the winter and spring of 1930 and in subsequent years building

neighborhood based Councils that fought for public assistance and

rallied neighbors to conduct rent strikes and resist evictions. But in

the Northwest

the Unemployed Councils were much less effective. Police

repression was one of the

problems. The Seattle Police Department maintained a policy of

permanent harassment all through the early years of the 1930s, arresting

Communists whenever they tried to hold a street meeting or a

demonstration, and routinely breaking up even in-door Party meetings.

Dozens of Party activists spent time in jail for the simple act of

trying to speak or attend a meeting. The usual charge was vagrancy, but

prosecutors also went after leaders with Criminal Syndicalism charges,

while those of foreign birth were threatened with deportation. The

American Civil Liberties Union and the International Labor Defense (the

CP legal team) managed to block most of the deportation orders affecting

Washington state Communists, but in Oregon the still more zealous

persecution of Reds resulted in some long prison terms and numerous

deportations. The Finnish community of Astoria was particularly hard

hit. The editors and staff of Toveri,

a Communist linked Finnish language newspaper, were arrested

and deported.[iii]

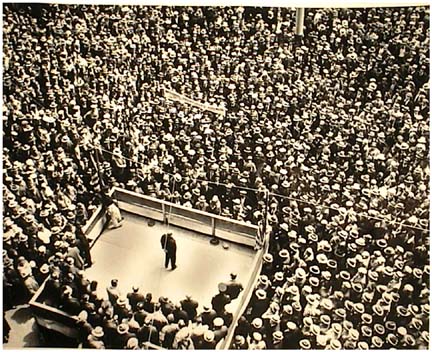

Mayor John F. Dore addresses a mass meeting of the unemployed in Seattle's city hall park. 6/6/32 MSCUA, University of Washington Libraries, Lee 20121

By the summer of

1931, the Unemployed Councils faced another obstacle, a rival

organization, the Unemployed Citizens’ League, formed

by socialists Hulet Wells and Carl

Branin, who directed the Seattle Labor College and published The

Vanguard,

a weekly newspaper. Wells and Branin set up the Unemployed

Citizens’ League as a self-help organization that provided practical

relief to destitute workers and their families. Within three months, The Vanguard reported a meeting involving representatives of 20

local UCLs from around Seattle. The organization was structured around

neighborhood commissaries where food, firewood and clothing were

dispensed. The self-help effort also included the operation of six shoe

repair shops and the cultivation of 450 acres.[iv]

The UCL quickly overshadowed the Unemployed Councils and within months had become a major social movement. In addition to services provided directly by its own members, the UCL commissaries received aid from the city of Seattle, King County, and sympathetic businesses. Between January 1 and July 12, 1932, the UCL self-help effort in Seattle had provided relief to 79,935 men and wood to 63,886 men. The cumulative labor provided in these endeavors and in the clerical effort necessary to run the commissaries was 2,306,415 hours of labor, according to Arthur Hillman who studied the organization in 1932.[v]

Published by the Seattle Labor College and edited by Carl Branin and Hulet Wells, The Vanguard was the voice of the Unemployed Citizen's League. For more on this important newspaper see the Vanguard report by Erick Eigner. Communists

were quick to attack the rival organization. Herbert Benjamin, a

national CP leader of the Unemployed Councils, labeled the UCL a “social fascist” effort that would lead to betrayal

of the workers and urged Seattle Communist

Party officials to build the Unemployed Councils.

Usually

the plans of rival organizations are not aimed to make our struggle more

effective, but on the contrary, to weaken our struggle and resistance to

the hunger policy of the bosses. Those who sponsor such

rival organizations do so for the personal and political advantages

which they gain by this means. Most of such organizations base

themselves on a so-called ‘self-help’ program. That is, instead of

struggle to force the bosses and government, who control the wealth, to

provide adequate relief and unemployment insurance, they advocate that

we, workers, shall help each other by sharing our poverty.[vi]

The Workers Alliance and Washington Commonwealth Federation replaced the Unemployed Councils and UCL in 1936. With help from the Workers Alliance, Mrs. Toll, a 63-year old chambermaid, wins a law suit to enforce the minimum wage law. (Sunday News April 8, 1937)

While the

CP-backed Unemployed Councils offered a hopeful future of jobs, respect

and benefits in a classless society, they did not match the concrete

offerings of firewood and sustenance that the UCL commissaries were

providing free of monetary charge. Given the choice, it appeared that

most Seattle unemployed preferred the immediate relief attained through

wood and food than some vague promise of salvation through Marxism.

Besides, Wells and Branin, both experienced in labor issues, also worked

on a political agenda to get bills through the Legislature that would

provide unemployment insurance, a jobs program and cash relief.

A similar situation occurred in Bellingham, where a small coterie belonging to the Communist Party (seven in number, according to Eugene Dennett) soon found their efforts upstaged by an organization called the People’s Councils, formed by Bellingham activist M.M. London. Similar to the Unemployed Citizens League, the People's Councils quickly coalesced into a strong movement that held mass meetings, staged demonstrations and resisted evictions. Elsewhere in the state, the ranks of the unemployed joined UCL locals or the United Producers of Washington., an affiliated organization.[vii]

Tensions erupted between Communists and these socialist organizations when various groups representing the unemployed embarked on a march to the State capitol in Olympia on July 4, 1932. The goal was a show of support intended to change the mind of Governor Roland Hartley, a traditional, pro-business Republican, who had steadfastly denied state funds for workers’ relief efforts. Hartley refused to meet the demonstrators, though he did meet a smaller delegation, including Hulet Wells, two days later. Despite the march’s obvious failure to affect state policy, it did provide visible proof of Communist intent.

According to Eugene Dennett, three CP leaders “fresh from the East” — Lowell Wakefield, Alan Max[viii] and Hutchin R. Hutchins — attempted to assume control of the massed demonstration gathered at Sylvester Park in downtown Olympia. Meanwhile, M.M. London led the UCL, United Producers and People’s Councils members in the direction of the capitol. The remainder of the crowd then marched under the Unemployed Councils’ banners “a considerable distance” behind the first group. Scuffles broke out when both groups arrived at the capitol:

A general fist fight followed and a dozen men were hurled six feet to the stone steps during the melee... The unemployed retained control of the pedestal and a stormy meeting ensued, with Communists heckling the speakers and creating a general disturbance. [ix]

By Dennett’s own account, he was forced by Wakefield and the

other CP leaders to publicly denounce London and his associates as

“social-fascist misleaders and betrayers of the workers.”

We never did

accept why the demonstrators did not flock to our standard.

We thought our program was so superior to theirs that we would have a

stronger appeal to all the demonstrators and we would win them to our

side. [x]

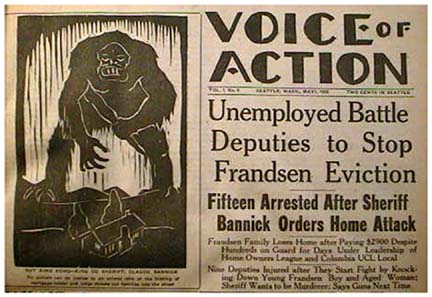

The Voice of Action did not proclaim its Communist Party affiliation, but its funds and staff came from the Party. Veteran party activist Lowell Wakefield served as editor. George Bradley, William Dobbins, and Alan Max were also involved. See the report on the Voice of Action by Christine Davies.

Even before the 1932 clash, Party activists had begun to develop a

second and ultimately more

successful strategy for dealing with the Unemployed Citizens League.

They would join! Although official policy required the building of

Unemployed Councils, Party members joined and became active in some of

the UCL units, initiating what became a protracted struggle for control

of that organization. Branin and the leadership of the UCL moved to

expel the Communists, and the

officers of the Ballard UCL were among those ejected for alleged

Communist sympathies. But as Hillman saw it, "the Victory for the

'safe and sane' elements was, however, short-lived."[xi]

In March 1933, the party began to publish the Voice of Action, a weekly newspaper that would compete with the Vanguard for readers and for influence in the now sharply divided unemployed movement. Persistence would pay off. Over the course of 1933, the Party would become more and more influential and the UCL would change focus, turning away from self-help activities and taking on the roles of agitation and education that the Party advocated. The expanded influence also paid off in a growing Party membership. Eugene Dennett recalls that in Bellingham in just one year "the party had grown from the seven original members to over 150 enthusiastic active members."[xii]

In Olympia, as nationally, the political tide was turning towards relief, help and jobs programs. Franklin D. Roosevelt campaigned in the 1932 election for programs to help the unemployed. But just as the Communists had derided the efforts of the Unemployed Citizens’ Leagues, so too were they critical of the new president and his announced plans to help the unemployed. In an editorial critical of Roosevelt, the Voice of Action of August 7, 1933, fumed

since

taking the oath of office, there has been a continuous evasion of

doing anything for the working class. Instead, the Bankers were

provided for first – when the banking holiday was declared: huge

loans (gifts) were made to the railroads and Big Business: a military

system of forced labor camps was instituted in the form of Civilian

Conservation Corps under the original name of ‘Federal Unemployed

Reserves,’ and now there has been enacted the National Industrial

Recovery Act, giving to the President all of the powers of a DICTATOR.

But as the New Deal emerged, Communists in Washington would also continue the practice of “boring within” to achieve leading roles in the projects relating to the unemployed. In the mid 1930s the Unemployed Citizens League would be replaced by the Workers Alliance, an organization that attempted to unionize and represent workers employed on WPA (Works Progress Administration) projects. Similarly the Party would organize its way into the Washington Commonwealth Federation, Washington Pension Union and various labor unions.

The early efforts with the unemployed set a pattern in which the Washington State Communist Party, never a broad-based mass organization, achieved a level of success far in excess of its membership, estimated to be between 3000 and 6000 at its peak in the late Thirties.[xiii] The party placed a relatively small yet highly effective group of motivated, astute, politically-active individuals as leaders of other left-leaning organizations. As such they were able to direct CP-inspired goals from within organizations that garnered more popular support than the Party could by itself. By gaining control of key positions within the Unemployed Citizens’ League (UCL) in Seattle, Communists in Washington may have achieved a greater degree of influence and, therefore, success than was the case in other parts of the United States.[xiv]

© Copyright Gordon Black 2002

Next: Organizing Unions: The '30s & '40s

[i] William H. Mullins, The Depression and the Urban West Coast, 1929-1933 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991), 92

[ii]Harvey Kiehr, The Heyday of American Communism: the Depression Decade (New York, Basic Books, 1984),

[iii] Albert Francis Gunns, Civil Liberties and Crisis: The State of civil Liberties in the pacific Northwest, 1917-1940 (Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Washington, 1971), 123-62.

[iv]Arthur Hillman, The Unemployed Citizens’ League of Seattle (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1934), 202

[v] Ibid.

[vi]Herbert Benjamin, How to Organize and Conduct United Action for the Right to Live (

[vii]M.M. London was Executive Secretary of United Producers of Washington. See Terry R. Willis, Unemployed Citizens of Seattle 1900-1933, Hulet Wells, Seattle Labor and the Struggle for Economic Security (Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Washington, 1997).

[viii]Max and Wakefield were later named in the masthead for The Voice of Action, a CP-run weekly started in competition to The Vanguard.

[ix]Lester Hunt, Seattle Post Intelligencer, July 5, 1932.

[x]Agitprop: The Life of an American Working-Class Radical: The Autobiography of Eugene V. Dennett (Albany: State University of new York Press, 1990)

[xi] Hillman, 205

[xii] Dennett, 45.

[xiii]Accurate

figures are hard to determine. Blood

in the Water (John McCann, Seattle: District Lodge 751, IAM&AW, 1989), a history of the

International Association of Machinists Lodge 751, quoted a peak

membership in the state of 6000; Jim West, a Communist Party work in

Seattle in the late Thirties, said in a March 2002 interview that

membership was “above 3000” in the state during the Thirties.

[xiv] For a comparison see James J. Lorence, Organizing the Unemployed: Community and Union Activists in the Industrial Heartland (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996)