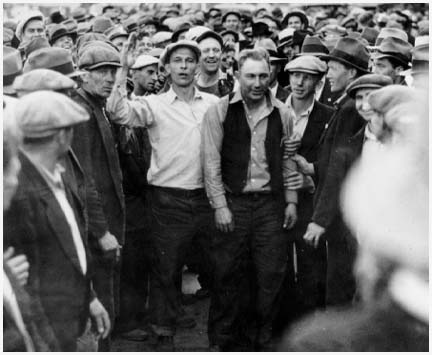

Tacoma and Seattle longshoremen lead a

strikebreaker, identified as 'Iodine' Harradin, off the Seattle docks

during 1934 strike. Harradin and other strikebreakers were removed under

a flag of truce as police stood back. Port of Seattle photo.

Ronald E. Magden Collection.The dawning of the Thirties saw the country sliding ever deeper into the Great Depression. Unemployment was soaring and would hit about 15 million by March

of 1933. Employed workers

were feeling less and less secure in their jobs, and the unemployed

could expect little help from the federal government.

This led to widespread unrest among the working class and

provided fertile soil in which the seeds of radicalism could easily be

planted. Many new recruits saw the Communist Party as a way to address

particular concerns: a

means of fighting fascism or racial, ethnic, and religious

discrimination, of gaining labor-union objectives, general social

improvement, or humanitarian socialist goals.[i]Others saw a more transcendent purpose, embracing the vision of

the Communist Manifesto in

which Karl Marx eloquently stated, "The history of all hitherto

existing society is the history of class struggles.”

After

1933 the Communist Party (CP) made great strides by switching from

activism in the unemployed sector to aggressive union building among

those who did have jobs. There

was a great upsurge in Communist participation and influence in labor

unions – especially in the Pacific Northwest. This participation brought the Party new members and new

credibility. In his book

Labor and Communism: The Conflict That Shaped American Unions,

historian Burt Cochran argues that the party gained influence and

credibility by taking the lead in union-building struggles and doing the

hard work of organizing and taking risks where others held back.

Party members gained a reputation as fighters for the working

class:

Beyond winning relief for some of the needy and making the country conscious of the national problem, the marches and demonstrations, the moving of furniture back into apartments whose tenants had been dispossessed, the countless sit-downs in relief offices and other so-called job actions were important in carving the image of Communists as intrepid fighters for the underdog.[ii]

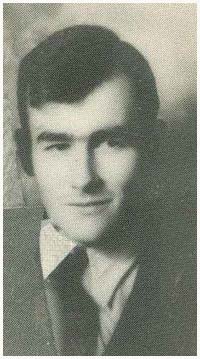

Burt Nelson was one the Party members who

helped rebuild unionism on the waterfront. A leader in the 1934

longshoreman's strike, he served during the 1940s as President of

the Seattle CIO Council. Photo: CPUSAThe

Pacific Northwest saw a great deal of Party union building activity

during the 1930s, although it is hard to figure the exact dimensions of

Party influence or the numbers of Communists in any particular union

since many wanted their affiliation kept secret due to fears of attack

and ostracism. One sphere

where Communists were effective was in the various industries where

there was a high percentage of immigrant workers. A

good example of this is the canning industry where the Cannery Workers

and Farm Labor Union that formed in 1933 was alleged to be

Communist-dominated.[iii]

The Alaska canning industry had a high percentage of Filipino

workers, some of who were drawn to the CP because of the Party's

position against racism and imperialism. Communists argued that one 'ism' existed because of the other

and that the Party was fighting against both.[iv]

(on the early years of the union see Filipinos

and the Cannery Workers Union by Crystal Fresco).

The cannery workers were initially organized under an AFL charter, but when the CIO formed in 1937 the Filipino-led union joined, at first affiliating with the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packers and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA), later becoming Local 37 of the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU). The leadership of the Alaska Cannery Workers union worked closely with the Communist Party. In 1949 five officers – Chris Mensalvas, Ernesto Mangaoang, Ponce Torres, Joe Prodencio, and Casimiro Absolor – were arrested, accused of being Communists, and threatened with deportation — a long legal battle followed. In 1954 the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that since the men had come to the U.S. before 1934, they were U.S. nationals and could not be deported.[v]

Communists

were equally influential in the maritime industry.[vi]

Working on the docks or on the decks and in the holds of

ocean-plying cargo ships is hard and dangerous work and it tended to

attract a transient workforce of rough and brawny men.

One of the main reasons why the waterfront workers were open to

Communist activity is that these men were used to visiting far off ports

and interacting with sailors on ships from all around the world.

This interaction led to an ability to accept and tolerate

differing opinions and beliefs and it is in this setting that radical

ideas were able to flourish. In 1934 the longshoremen reorganized under the leadership of

Harry Bridges who was an Australian seaman. This organization of

longshoremen created a powerful union that would play an ongoing and

pivotal role in the West Coast maritime industry.

Initially affiliated with the International Longshoreman's Union

(ILA), the West Coast locals joined the CIO in 1937 and became the

International Longshoremen and Warehousemen's Union (ILWU).

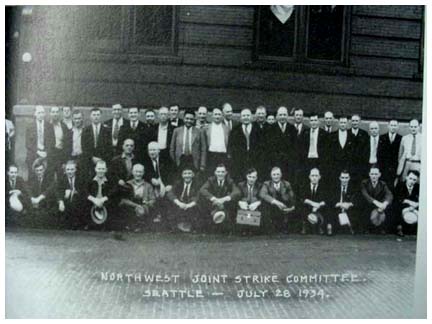

Joint Northwest Strike Committee outside

Seattle Labor Temple, 1934. Courtesy Pacific

Northwest Labor History AssociationThe

CP was very involved on the waterfront and in 1934 – the year of the

great West Coast waterfront strike – the Party played an important role

in the strike and in outlining the demands. A friendship and fellowship

formed between Bridges and another Australian seaman named Harry Hynes,

who was the founding editor of the Waterfront

Worker, a Communist paper in San Francisco.

While there has always been controversy over whether or not Harry

Bridges was himself a member of the Communist Party, it is widely

accepted that the Longshoremen's Union had one of the most radical and

leftist track records of many of the unions operating at the time.

Whether or not Bridges was a Communist, the ILA (which became the

ILWU in 1937) pursued many ideals and beliefs that were central to the

CP and its efforts within the labor movement.

Another

important labor conflict where the CP played an important role – and

particularly a specific member of the Party – was the American Newspaper

Guild strike of the Seattle

Post-Intelligencer in 1936. Terry

Pettus, a Party member and the first Northwest reporter to join the

Guild while he was working in Tacoma on the Tacoma

Ledger, was an ardent fighter for unions, against racial

discrimination, and for better housing and rights for poor and working

people.[vii]

Pettus had been raised in a home where a social conscience and a

willingness to act on behalf of man were considered the measure of a

person's worth.[viii]

In 1936 the Party sent him to Seattle from Tacoma to start up a

chapter of the Guild. Within

a few months he had recruited about 35 co-workers at the P-I

into the Guild; some of the other members of the Seattle chapter

came from The Voice of Action, the

organ of the CP in the Northwest.[ix]

The Guild Striker was the official paper of the 1936 Newspaper Guild strike against the Seattle P-I. For more information on this paper click the title above.The

owner of the Seattle P-I was

none other than William Randolph Hearst, the newspaper mogul who owned countless papers

nationwide and was fervently anti-labor and anti-Communist.

Hearst, an open admirer of Hitler and of what the dictator had

done for Germany, was quoted as saying, "Fascism will only come

into existence in the United States when such a movement becomes really

necessary for the prevention of Communism."[x] Obviously, Hearst was loath

to welcome a union at his Seattle newspaper, especially one that was

founded and led by a Communist. The

first big test for the fledgling union came when management fired two

long-standing and well-respected writers on the P-I staff, thereby pushing the Guild members to act.

The firings were added to the long list of staff complaints that

included policies such as hiring young, inexperienced writers who were

willing to work longer hours for less pay, firing longtime-staffers to

make room for these upstarts, and a flat-out refusal by the executive

staff of the paper to recognize the Guild chapter.

Finally, the fledgling union had the impetus it needed to take on

the brute forces of Hearst.

On

the morning of August 8, 1936, thirty-five Guild members set up a picket

line outside the Seattle P-I

offices that stood at the intersection of Sixth Avenue and Pine Street

in downtown Seattle. These

were not the burly, strong men of the waterfront or lumber camps, these

were reporters, librarians, and key editors – but that did not matter

for they were labor and a united front of labor answered their call for

help.

The pickets scarcely had time to adjust to their new

situation before

they found themselves being elbowed aside as the more

powerful and experienced labor elements of Seattle moved down from the

hills, up from the waterfront, and out of the Labor Temple.

A phalanx of labor's more experienced fighters moved up from Skid

Row to the respectable business district [from the waterfront].

There, joined by metal workers, lumber workers, and other member

of the labor movement, they formed

a line around the Post-Intelligencer plant. ...By noon, Teamsters were pouring into

the lines around the newspaper.[xi]

What started as thirty-five now grew to over 1,000 picketers

surrounding the building. They

were even joined on the picket line by the Mayor of Seattle, John Dore,

who was successful in his mayoral bid due in large part to the support

of labor. This was a strike

of the entire labor movement in Seattle that mobilized against Hearst

and everything he stood for. The

paper was shut down, and by November 25th the Guild had achieved its

goal: William Randolph

Hearst was forced to formally recognize the Seattle chapter of the

American Newspaper Guild. Among

the stipulations of the settlement were the establishment of a

forty-hour week in six days until March 1, 1937, and a forty-hour week

in five days thereafter; sick leaves with full pay; two-week vacations

for employees of more than one year; and a severance plan with one

week's pay for each year after one year and up to five weeks.

While this strike was a victory for all of organized labor in

Seattle, it owed much to the CP whose members not only started the Guild

local and worked fervently to support it, but also refused to abandon it

in a dark time and pushed many to stand up to overwhelming odds and take

on a fight that few believed could be won.

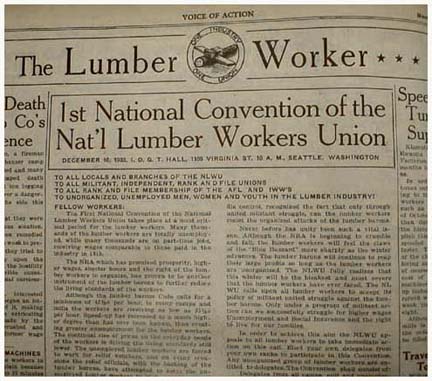

Communists were also present at the forming of a union that

represented workers in the lumber and pulp mills and in timber camps

throughout the Northwest. Loggers,

miners, and seasonal agricultural workers had formed the core of the

Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in the years leading up to World

War I. This early

organization found success organizing in the Northwest logging camps by

promoting industrial unions that would bring all the workers in the

industry under one umbrella union.

They believed in worker ownership of factories, a 40-hour work

week, and sanitary conditions in the logging camps – and for believing

in these 'rights' they were branded as dangerous radicals.

An example of the strength of the IWW in the logging industry of

the Northwest came in 1917 when 50,000 lumberjacks went on strike and

shut down the entire industry from Northern California to British

Colombia, Canada.[xii]

But during the 'red-scare' of the early Twenties the government

cracked down on the IWW and all but squashed it, yet its legacy lived

on – especially in the lumber industry.

This

legacy rematerialized on September 18, 1936 at a convention in Portland,

Oregon, where the Lumber and Sawmill Workers, the Plywood and Veneer

Workers, the Box Shook Workers, the Shingle Weavers, the Boom-men and

Rafter-men, the Furniture Workers, the Pile Driver Workers, and many,

many more all united under the Federation of Woodworking Unions,

bringing together approximately 72,000 workers under one banner, later

renamed the International Woodworkers of America (IWA).

By uniting all those workers whose trades revolved around the

manufacture, manipulation, or finishing of material made of wood under

the single banner of the IWA, the spirit of the IWW was handed down to a

new generation of lumbermen in the Northwest.

The

formation of the IWA was in direct response to grievances against

William Hutcheson, President of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and

Joiners (AFL) for his ultra-conservative policies and his mishandling of

the dues paid by the lumbermen. Hutcheson

took the dues paid by the Northwest lumbermen and refused to allow them

a vote in union matters, prompting the lumbermen to form their own

union, the Federation of Woodworking Unions (later the IWA), and

threaten to join the CIO. The General Secretary of the Carpenters’ responded that if

they proceeded with their threats to leave the AFL and join the CIO, the

lumbermen would get "the sweetest fight you ever had."[xiii]

Under the leadership of Harold Pritchett, who was named by

several people as being a member of the Communist Party,[xiv]

the IWA moved towards affiliation with the CIO and left the Carpenters.

The IWA had close ties to Bridges' ILWU, since all of the lumber

that they handled eventually led to the waterfront, where it was shipped

off throughout the world. A

friendly relationship with the longshoremen made their work easier.

They were also very involved in organizing drives throughout

Washington among different crafts like match workers in Tacoma and

lumber mill workers in Elma, Everett, and Longview.

Party members were also involved in the organization of the Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers Union, which later became ILWU Local 37. Filipinos working in the Alaska salmon canneries in the summer and the "farm factories" of California and eastern Washington in other seasons were the heart of this union. Photo courtesy ILWU Local 19, Seattle. For more see see Filipino Cannery Unionism Across Three GenerationsThe

official paper of the IWA was originally The

Timber Worker (later called International

Woodworker), which was published out of Aberdeen, and had a

circulation of about 25,000 in 1938, reaching 39,000 in 1940.

While the paper was never overtly Communist, the Party exercised

editorial control. Nat

Honig, former editor of the Waterfront

Worker — the

CP’s San Francisco paper — moved to Seattle in 1937 to edit The

Timber Worker.[xv]

The newspaper featured articles and opinion pieces that

discussed issues that tended to be very communistic in nature,

discussing anti-fascism, class solidarity, intense anti-war sentiments,

and civil and women’s rights. The

IWA remains a good example of where a long tradition of radicalism and

fraternalism survived attacks from all sectors of society, yet the

spirit of the laborers never dimmed and their goals were never

forgotten.

Communists may also have been involved in the formation of

District Lodge 751 of the International Association of Machinists and

Aerospace Workers, representing Boeing workers.

This union first formed in 1935 as Local 751 of the International

Association of Machinists, which was an AFL-affiliated international.

Starting with a mere 35 members, the local quickly grew to just

over one thousand in 1937 and by May of 1939 boasted a membership of

about 2,100.[xvi]

While it is hard to pinpoint specific members of the CP involved

in the efforts to organize this union, in 1940 Cliff Stone — editor of

the Aero Mechanic, the

official paper of the union — issued an unauthorized edition of the

paper in which he accused over 50 members of the union of belonging to

the CP. Among those named

were Barney Bader, President of Local 751, and Business Representative

Hugo Lundquist. These two

men were eventually expelled from the union and fined, having been

"found guilty of subversion — that is, being advocates of

Communism..."[xvii]

While this does not necessarily mean that these men were Communists, it

does go to further suggest that the CP was involved in all imaginable

industries and unions and that its presence was felt almost everywhere.

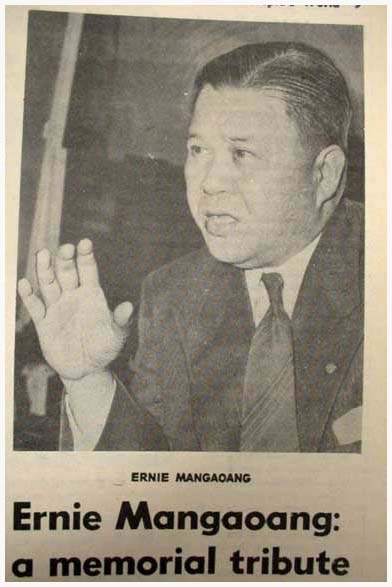

Born in the Philippines in 1902, Ernesto Mangaoang helped organize the Alaska Cannery workers and held a succession of top offices in the Cannery Worker's and Farm Laborer's Union. His death in 1968 prompted this memorial tribute in the Peoples World June 8, 1968. Another CP-influenced union formed on the campus of the

University of Washington in 1935 with the formation of Local 401 of the

American Federation of Teachers. While

the Local was part of the AFL, several outspoken members like Harold

Eby, Hugh DeLacy, and Ralph Gundlach – all were named as members of the

CP at one time or another – argued for affiliation with the CIO.[xviii]

While the union kept moving farther and farther to the left and

tended to support the "Communist line," the President of the

University, Lee Paul Sieg, felt that its 'leftist' activities might

cause the Legislature to interfere in the internal affairs of the

university.[xix]

Little did he know how right he was, for in a move that was a

possible foreshadowing of what was to come, on January 23rd of 1939

State Representative D. L. Underwood (D-Seattle) called for an

investigation by the House of Representatives into 'communist

activities' at the University of Washington to see if the state could

stop the UW from hiring Communist speakers or professors.

He was reacting to the University's plan to hire Harold Laski, a

well-known British Marxist, to lecture on campus about the aims of the

British Labor Party. Laski

was ultimately paid by a private endowment and did not use any state

funds, but the actions taken by Representative Underwood stand out as

another case of red-baiting and show what people were facing when they

openly associated themselves with the CP or any kind of Marxist

teachings. This was to be

only the beginning of the hunt for 'reds' on the campus of the

University.

Next: The Washington Commonwealth Federation & Washington Pension Union

[i]Bert Cochran, Labor and Communism: The Conflict that Shaped American Unions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977), 12.

[ii]Ibid., 79.

[iii]www.californiahistory.net

[iv]Jay Mendoza, "Anti-Imperialist Struggle and Resistance Among the Filipino Community in the U.S." www.geocities.com/CapitolHill/Lobby/4677/jay-pa.htm

[v] Fred Cordova, Filipinos: Forgotten Asian Americans (1983), 73-80.

[vi]Cochran, 58.

[vii]Ross Reider, Terry Pettus (1904 - 1984). www.historylink.com

[viii]William E. Ames and Roger A. Simpson, Unionism or Hearst: The Seattle Post-Intelligencer Strike of 1936 (Seattle: Pacific Northwest Labor History Association, 1978), 11.

[ix]Ibid., 17.

[x]Ibid., 16. This quote was apparently taken from a book by Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., The Age of Roosevelt: The Politics of Upheaval (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1960) 85.

[xi]Ibid, 60-61.

[xii]Ross Reider, Industrial Workers of the World - A Snapshot History. www.historylink.org

[xiii]The Timber Worker. This was the official newspaper of the IWA and it reported the Duffy quote in an issue sometime near the end of 1936, most definitely after the convention.

[xiv]Hearings before the Committee on Un-American Activities; House of Representatives, Eighty-Third Congress. June 14-19, 1954. Pritchett was named by John P. Frey who was President of the Metal Trades Department, AFL; Harper L. Knowles who was the chairman of the Radical Research Committee of the American Legion, Department of California; by Captain John J. Keegan who was Chief of Detectives for the Portland, Oregon Police Bureau and others. Of course this is highly biased testimony, but it can be looked on as being somewhat credible because Pritchett was so often named.

[xv]Canwell Hearings, Nat Honig testimony, 228.

[xvi]John McCann, Blood in the Water: A History of District Lodge 751, International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (Seattle: District Lodge 751, 1989), 25.

[xvii]Ibid., 37.

[xviii]Jane Sanders, Cold War on the Campus: Academic Freedom at the University of Washington, 1946-64. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1979), 24. All three of the mentioned men were named in the Canwell hearings..

[xix]Ibid., 7.