New World February 5, 1948The Communist Party of Washington State went through numerous changes from 1940 to 1960. World War II and then the Cold War dramatically affected the Party’s fortunes and ability to function. The Red Scare of the late 1940s and early 1950s nearly destroyed the Communist Party, driving away most of its members. Some of the Washington State leaders were imprisoned, others went underground.

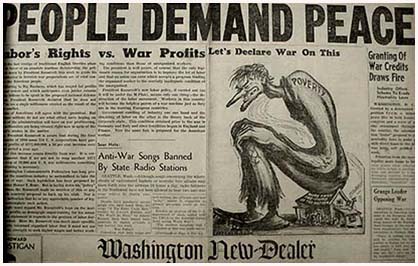

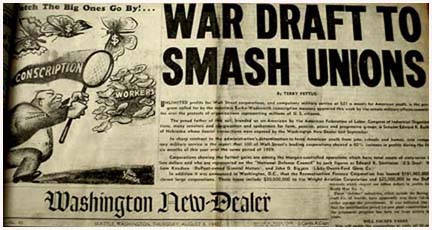

In the two years from 1939 to 1941, Communists in the United States witnessed stark changes in how the public responded to the Party. In 1939 Stalin signed the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact, and the Communist Party immediately adopted an anti-war posture. The Washington New Dealer, published by the Washington Commonwealth Federation and closely affiliated with the Communist Party, reflected this policy shift in glaring headlines denouncing war preparations. (Take a look at some of these headlines.)

When Stalin signed the non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany in 1939, the Communist Party turned from fighting fascism to advocating peace. The Washington Commonwealth Federation newspaper vigorously promoted this new line. May 23, 1940Communists were confronted with great animosity from the general public because they were perceived to be cooperating with Hitler. Many Party members quit. Michael Reese, author of “The Cold War and Red Scare in Washington State,” an extensive online resource, explains:

Overall, the CP’s membership in Washington State declined by more than half in 1939 and 1940 as most Party members could not stomach the new tolerance of Hitler and were repulsed by the willingness to follow a “Party line” dictated in Moscow. Many people who left the Party in this period were so embittered that they later testified against the CP during the late 1940’s and 1950’s and welcomed the persecution of communists.

The Hitler-Stalin pact was short lived. In 1941 the Nazis terminated it with their invasion of the Soviet Union. After Pearl Harbor, the United States and the Soviet Union became allies, which took some of the pressure off the CPUSA. Now the Communist Party

By 1940, CP opposition to the defense buildup was hurting the WCF. August 8, 1940wholeheartedly cooperated in the U.S. war effort, declaring that the class struggle must be subordinated to it. Michael Reese goes on to say:

The American Communist Party abandoned its calls for social reform and became downright conservative. The CP cooperated with employers to put down strikes during wartime, and urged people to work longer hours without pay increase.

This cooperation was readily seen throughout Washington State in Communist-affiliated newspapers. “Communists in Pledge for War,” headlined the Washington New Dealer in December of 1941:

CPUSA pledged its unqualified loyalty in the war against the Axis powers . . in common with all other patriotic Americans, the Communist Party stands at attention for the services of the nation in its just causes.

Though the membership of the Washington State Communist Party rose with the Allied support of the USSR, one former member explained that it still “never fully recovered in the public mind-set because of the residual antagonism to the Communist Party and its followers.”[i]

This new all-out support for the war effort was seen as a mistake by some Communist members. Eugene Dennett, Washington Communist Party member from 1931 to 1947, recalls how the transition from fighting for civil and workers’ rights to a more nationalistic policy affected the Party:

I was disturbed because there were no remains of the Party unit I had led in Rainier Valley before joining the army.

The people who used to be active in it seemed to no longer have any ties to our equal rights efforts for Negroes and women. Before I left for the army, our Party unit had recruited about 150 members around the issues of equal rights for women and the many minorities that had deep roots in the Rainier Valley area. Our Party unit was inspired by the public response to our efforts to stop discrimination against any minority.[ii]

Washington's Cold War red scare began late in 1947 when the Republican controlled legislature authorized Albert Canwell to investigate the activities of Communists. Representative Canwell meets with the commitee at the start of hearings in January 1948. Photo. Museum of History and IndustryRep. Albert Canwell surrounded by members of the Canwell Committee. Photo from Museum of History & Industry, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, no negative number (filed under A. L. Canwell, 1/15/48)Though World War II had come to an end with the defeat of Germany in 1945, the threat of a Cold War was already pressing upon the nation. To ensure support for the Cold War abroad, the Truman Administration paralleled its foreign policy of containment overseas with a full-out anti-communist crusade at home. Making anti-communism the focus of their 1946 campaign, Washington Republicans charged that “Democrats had sold their soul to the Communist Party.”[iii] The State Republicans’ determination proved fruitful when the 1946 elections ushered many of them into the State Legislature.In 1947, Albert Canwell, one of the newly elected Republicans, introduced a resolution to “create a committee with broad

powers to investigate organizations whose membership includes communists.”[iv] According to Canwell:

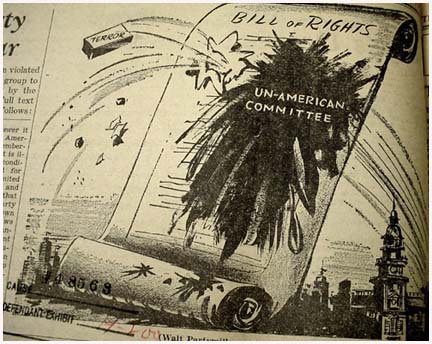

These are times of public danger; subversive persons and groups are endangering our domestic unity, so as to leave us unprepared to meet aggression, and under cover of protection afforded by the Bill of Rights these persons and groups seek to destroy our liberties and our freedom by force, threats and sabotage, and to subject us to domination of foreign power.[v]

Canwell’s resolution passed by a large margin, and the newly-founded Joint Legislative Fact Finding Committee on Un-American Activities elected Canwell chairman. The Canwell Committee, in hopes of eradicating the Communist Party, held public hearings that would expose the Party. The Canwell Committee argued that:

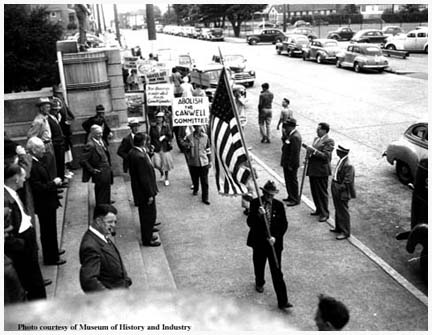

Anti-Canwell protesters march outside the Washington State Armory, where the Canwell hearings were held. The Armory was located just a few blocks away from the present site of the Space Needle. Photo appears courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry, Seattle, Washington (Seattle Post-Intelligencer collection, negative #121683).Communism cannot function in the light of day. We feel that with the publicity given their activities during the course of this hearing, that the people of the State of Washington will properly and adequately take care of Communism.[vi]

These public hearings, however, were one-sided. Persons accused of being Communists could not cross-examine their accusers nor make their own statements. Moreover, the Committee also turned to professional anti-communist witnesses who testified that:

the American CP was subservient to Moscow, that communists' participation in seemingly reformist “front” groups was simply a ruse to attract soft-headed liberals the CP wanted to convert, and that the ultimate aim of the CP was the violent overthrow of the US government.[vii]

Many of the accused were not active party members. Some had been members but had left years before. A few may never have been Communists. But regardless of their relationship to the Party, those targeted would pay a heavy price. The accusations were damaging to reputations and cost many their jobs. The Canwell investigations, as well as the later investigations by the House Un-American Activities Committee, left many Communists and former Communists blacklisted.

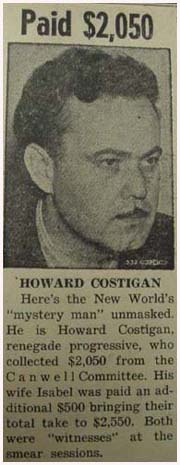

Howard Costigan's testimony was not particularly damaging, but when the former Executive Director of the Washington Commonwealth Federation and former Party member agreed to testify before the Canwell committee, his former comrades were shocked. The Party tried hard to discredit him. New World September 23, 1948The most publicized example involved six tenured professors at the University of Washington. Seeking to “clear the University’s reputation,” administrators prepared to dismiss Garland Ethel, Harold Eby, Melville Jacobs, Joseph Butterworth, Hebert Phillips, and Ralph Gundlach, charging them with incompetence, neglect of duty, incapacity, dishonesty or immorality. A faculty committee was established to determine whether tenure should be revoked. Hearings that lasted for three months came to a close during December 1948 with the Tenure Committee voting to dismiss Gundlach and retain the five other professors.

These recommendations, however, were ignored, and the UW Regents in January 1949 declared that Butterworth, Phillips and Gundlach would be discharged, while Eby, Ethel and Jacobs would be placed on probation for two years and required to sign loyalty oaths. Butterworth, Phillips and Gundlach never worked in academia again. Butterworth, a teacher of Chaucer and English, went on public assistance. Phillips, a philosophy professor, was forced to become a laborer.

The Canwell investigations and the UW case were early episodes in the Cold War persecution of Communists. Anti-communist fervor would reach new heights during the early 1950s as Senator Joseph McCarthy grabbed headlines. The federal government jailed Communist leaders under the Smith Act and passed a tough new law, the McCarran Act, also known as the Internal Security Act of 1950, that required registration of organizations and their officers and members as “communist-action,” “communist-front,” or “communist-infiltrated.”

As this nationwide Red Scare accelerated, Communist Party members were forced to take refuge underground. According to B.J. Mangaoang, herself a Communist member since 1936, approximately ten to fifteen individuals went underground during the early 1950s. Mangaoang was one, and in an interview for this project, she recalled why these precautions were necessary:

The judgment was that fascism was very close. In order to continue work, the majority would be here walking around, but there would also be a group that was not visible - they walked around, but not under their name.[Though] I don’t think it was necessary at that point because I think it was a misjudgment of what the situation was politically, it was nevertheless a very invaluable experience because it was a learning experience for me personally and for the Party.

By 1952 the federal government’s crusade against communism had reached Washington State. Seven leaders of the Washington State Party were arrested, charged under the Smith Act with conspiring to overthrow the U.S. government. Though the defendants, later known as the Seattle Seven, provided ample documentation that they had never openly advocated the overthrow of the government, six were found guilty and sentenced to five years in jail and were fined ten-thousand dollars each (the other defendant, WPU President William Pennock, had committed suicide during the trial). Following her conviction in 1952, Barbara Hartle, one of the Seattle Seven, became an informant for the FBI.

Professor Ralph Gundlach, attorney John Caughlan, and state Communist Party Secretary Clayton van Lydegraf wait for the regents to rule on Gundlach's case. The regents voted unanimously to fire Gundlach. Photo courtesy of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, Museum of History and Industry. For more on the case: Nancy Wick "Seeing Red" Columns December 1997.In 1954 and 1955, the House Un-American Activities Committee focused its energies in Seattle. Hartle, informant for the FBI and star witness for HUAC, accused hundreds of having Communist affiliations. Reese further explains:

Hartle listed literally hundreds of people she had seen at CP meetings, including minor WPU functionaries and people who had only attended three or four communist gatherings before dropping out of the Party. Many of the people Hartle named had left the CP over fifteen years earlier, and some vehemently denied they ever had anything to do with the CP.Although very few of those named during the HUAC hearings lost their jobs, many of them found their friends and colleagues suddenly unwilling to talk to them or be seen with them.[ix]

Irene Hull, Washington Communist Party member since 1942, was one of the hundreds named by Barbara Hartle. In 1954, Hull was publicly accused on television of being Communist. Interviewed for this project, Irene recalled her experience:

She [Hartle] named a whole raft of people, many of whom she did not know. When she named me she called me a Trotskyite. I was very anti-Trotskyite. My mother-in law had a tv downstairs. She said, “You better come down here. I heard your name. So I went down and Barbara said it again. They always made sure that it got repeated so that more people heard. And my mother-in-law said, “What?”

Though Hull never testified before HUAC, she was not left unscathed by these accusations. She lost several jobs and quite a few friends

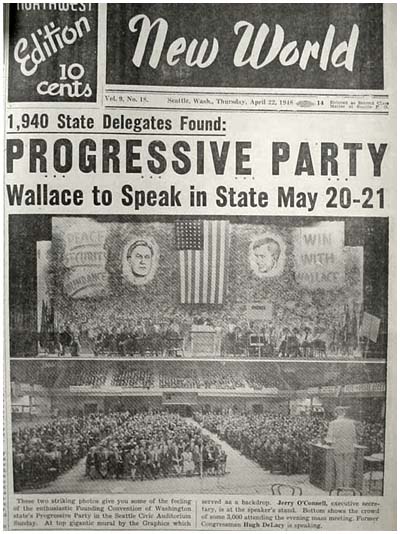

Communists backed the third-party candidacy of former Vice-President Henry Wallace in 1948 and hoped that his peaceful, co-existence foreign policy plans would bring an end to Cold War antagonisms. A huge crowd greeted Wallace when he spoke in Seattle. (New World April 22, 1948)Hartle was not the only ex-Party member to testify against the Communist Party. Expelled from the Communist Party in 1947, Eugene Dennett also became a key witness during HUAC’s investigations. Though Dennett invoked the Fifth Amendment when he first testified in June 1954, he later openly testified against the Party in March of 1955. Dennett explains why such testimony was necessary:

The men I worked with told me that the only way I would be able to stay on the job would be to testify without hiding behind the Fifth. They insisted that I would appear to be guilty of something if I did not testify and this would worsen my problems. It was March, 1955, before the Un-American Committee returned to Seattle. Most of my testimony dealt with official Communist party policies. I tried to explain the main shifts in Party policy which occurred during the time I was in the Party, and explain that we Communists had tried to do something for the hungry victims of the Depression. The Committee demanded that I name others with whom I had worked in the Party. I did so under protest, reluctantly and apologetically. I had to confirm Barbara Hartle’s testimony regarding the Party’s policies and the names of members. I believe my testimony did not, for the most part, hurt anyone more than they had already hurt.[x]

Though Dennett claimed “personal and moral objections to naming people,” his former comrades regarded him as a willing turncoat. The People’s World labeled him a star-performer and a fake.

Understandably, many members left the Party during these turbulent years. The 1948 demise of The New World, a Seattle-based paper, suggests that the Party was having financial and membership difficulties. The Party was forced to consolidate its West Coast publications; henceforth, the Daily People’s World, published in San Francisco, would serve the entire region. A local newspaper was no longer sustainable in the State of Washington. The final edition of The New World headlined:

New World Suspends! With this issue, The New World brings to an end a ten-year career of fighting in the deepest interests of the common people, not only of our state but of the nation and the world. To put it bluntly, The New World is stepping aside to make possible the rapid and full growth of people’s newspapers in the Pacific Northwest that these critical times demand. On Nov. 27th, the Daily People’s World is scheduled to begin publication of a special Northwest Edition of its weekend newspaper--a publication which The New World hasn’t the facilities or the funds to duplicate. While our circulation revenue, during the past year, has greatly increased, it has not kept pace with mounting production costs.

A moment of relief: Albert Canwell was defeated in the 1948 election and his committee was disbanded when the new legislature convened in 1949. By the mid 1950s the Washington State Communist Party was a shadow of its former self. Hounded by the FBI , by state agencies, and private anti-communist groups, the Party spent much of its energy and money on legal defense. Its once impressive infrastructure of union caucuses and affiliated organizations was largely gone. The Washington Commonwealth Federation had disbanded, the Washington Pension Union had been placed on the Attorney General's list of "subversive organizations" and barely functioned.

© 2002 Stephanie Curwick

Next: A Partial Revival: The 1960s

[i]Eugene V. Dennett, Agitprop: The Life of an American Working-Class Radical (New York: State University of New York Press, 1990), 116-117.

[ii]Ibid., 136.

[iii]Quoted in Reese’ website “The Cold War and Red Scare in Washington State.”

[iv]For a more detailed account and documentation, please refer to

www.washington.edu/uwired/outreach/cspn/curcan/main/html.

[v]Quoted in the Resolution to the House No. 10. For a more complete description and account of the UnAmerican activities, please consult First Report: Un-American Activities in Washington State: 1948, which provides the complete testimonies of those called into question.

[vi]View held by Canwell Committee, as quoted in M.J. Heale, McCarthy’s Americans: Red Scare Politics in State and Nation, 1935-1965 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1998).

[vii]Quoted in Reese’s website “The Cold War and Red Scare in Washington State.”

[viii]For a more detailed account of the Red Scare, please see Reese’s website; Bert Andrews, Washington Witch Hunt (New York: Random House, 1948); or Rader’s personal account in False Witness [by] Melvin Rader (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1969).

[ix]Quoted in Reese’s website “The Cold War and Red Scare in Washington State.”

[x]Dennett,