Still an important political force

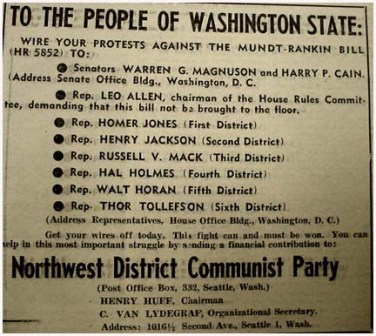

in Washington state in 1948, the CP mounted a public campaign to defeat

the "Subversive Control Act" that Congress considered

that year (New World May 6, 1948)

Much of the literature on American Communism has revolved around an intense debate over the legitimacy of the movement. What was the nature of its relationship to the Soviet Union? Why did it resort to secrecy in so many of its operations? Did its organizational practice-- top-down decision making and the expectation that members would accept Party discipline--place it outside the boundaries of American political practice?

Answers have fallen into three basic camps. A huge literature fixes the Communist Party as an "un-American" organization and finds no legitimacy in anything it did. Loudest during the Cold War decades, this perspective remains strong even today, best exemplified in the writings of Harvey Klehr, John Earl Haynes, and Ronald Radosh,.[1] A second perspective, the Party's own position, explains controversial matters of practice and polity on the grounds of necessity, and stresses the contribution of Communists to many of the labor and social justice projects of the 20th century.[2] A third body of scholarship has taken up the last point. Call it the New Labor History position, it has been the perspective behind the largest number of books published in the past thirty years. Not uncritical of the movement and especially its undemocratic practices, these scholars nevertheless credit the Party with making substantial contributions to the building of the CIO in the 1930s and to the early phases of the Civil Rights movement. They also point out that the Cold War purges of Communists did lasting damage to the prospects for labor-based politics in America.[3]

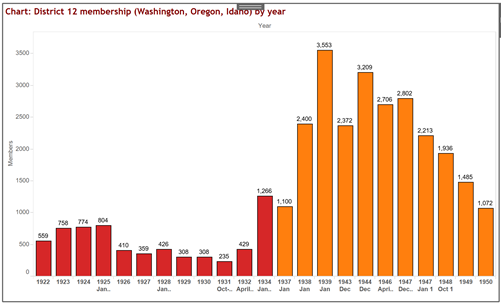

Chart shows year-by-year membership. Click for larger version and interactive map and data.

This

project was not designed to contribute directly to the on-going debate.

We neither have the tools nor the context to reach broad conclusions

about the nature of the Communist Party in America. Our goals are for

the most part quite modest. From secondary and primary sources we have

tried to develop a narrative account of the Communist Party in

Washington State from the birth of the movement in 1919 to the end of the century. We have focused on basic questions of organizational growth and

organizational strategy, describing what Party members did and tried to

do and the contexts in which they operated. Our starting proposition is

that this is a political organization that has in various ways been

important to the history of Washington state.

That importance has little to do with numbers. In the 1920s there were but a few hundred Communists in the state. Membership peaked in the late 1930s when Party sources recorded between 2,000 and 3,000 members in District 12 (Washington, Oregon, and Idaho). The numbers declined somewhat in the 1940s and fell off precipitously during the Cold War. As of 2002, there were perrhaps 60 members of the Washington state branch of the CPUSA.

Nor could it be said that the Party ever enjoyed public legitimacy. Whenever the Party operated openly, it was regarded with hostility. A chart of the various electoral campaigns in which Communists ran on Party identified tickets shows how little public support it drew:

| Year and candidate | Washington state vote |

| 1924 William Z. Foster (President) | 761 |

| 1928 William Z. Foster (President) | 1,541 |

| 1932 Earl Browder (President) | 2,972 |

| 1934 George Bradley (Senator) | 3,470 |

| 1940 Earl Browder (President) | 2,626 |

| 1950 Herbert J. Phillips (Senator)* | 3,120* |

| 1984 Gus Hall (President) | 814 |

| * Phillips ran as an

independent Source: Washington Secretary of State, Abstract of Votes |

|

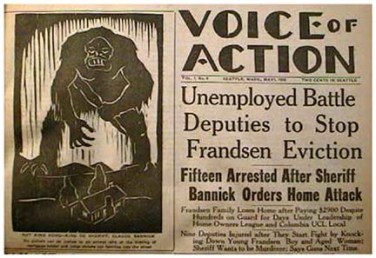

The Voice of Action was the first of a series of CP-linked

weekly newspapers published in Washington state in the 1930s and

1940s. Noted for its high quality writing, powerful graphics, as well as

its editorial fire, the Voice of Action and its successors were

critical to the growing influence of the CP. More on the Voice

of Action.

But Party effectiveness did not depend on numbers or popularity. Resourcefulness and dedication were the keys to a pattern of activism that for a time made the Communist Party highly influential in Washington State. Beginning in the early 1930s with work among the legions of unemployed, Communists organized their way into leadership positions in various left wing and labor organizations. Sometimes helping to start them, sometimes moving into existing organizations, Communists became involved in the whole complex of activities that made up the New Deal in Washington State. These included key unions in the maritime, timber, cannery, aircraft, and service sectors. They included a succession of important organizations that represented those out of work or dependent on public assistance (Unemployed Citizens League, Workers Alliance, and Washington Pension Union). And most importantly, they included the Democratic Party, which the Communists influenced through the Washington Commonwealth Federation, a caucus organization that controlled Democratic Party machinery in some parts of the state and nominated candidates for office.

Much of this influence was semi-secret. Communists involved in the unions and political organizations for the most part did not reveal their Party affiliation, and the extent to which Party "fractions" controlled these operations was not publicized. But at the same time Party influence was not altogether secret. Alert Washingtonians knew the score and could roughly identify the activities and organizations where Communists were involved.

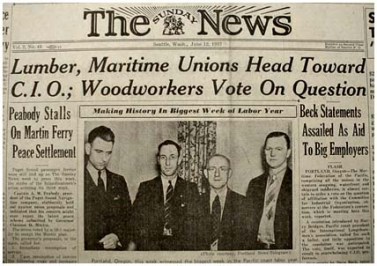

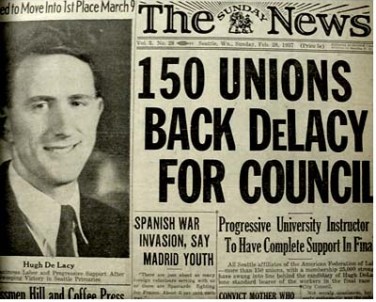

Another CP-linked newspaper, the Sunday News, headlines the decision of two of the region's most important unions to join the CIO in 1937. Communists were part of the leadership of both the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union and the International Woodworkers of America.It was

less well known that quite a number of the politicians who won elections

as Democrats were secret Communists or working closely with the

Communist Party. Hugh DeLacy, who was fired from his job as a lecturer

at the University of Washington when he began working with the

Washington Commonwealth Federation and running for office with WCF

support, served several terms on the Seattle City Council and two terms

in the US Congress without disclosing his Party connections. Other

Communist Democrats served in the state legislature and held various

other political offices.

The capacity to endure persecution was another feature of the Party's unique political presence. Three times the Communist movement was driven at least partly underground -- in the early 1920s, during the Hitler-Stalin pact years, and most seriously in the Cold War era. Yet each time it survived, weakened but unbeaten. Even when there was no active Red Scare, it was hardly safe to be an open Communist. All through the 1920s and early 1930s, Party members suffered harassment and arrests, including felony charges of Criminal Syndicalism. The legal pressures eased for one decade (roughly 1934 to 1947) before resuming during the Cold War.

The second Red Scare began in Washington state in 1947 when the legislature established a "little HUAC" committee chaired by Albert Canwell, Republican from Spokane. The Canwell committee staged two sets of high-publicity hearings designed to expose Communists and Communist sympathizers in important institutions, including unions, political organizations, the Democratic Party, and on the faculty of the University of Washington. This initial Cold War crusade and those that federal authorities conducted over the next half dozen years succeeded in destroying the influence of the Party and drove away much of its membership.

Hugh DeLacy won a seat on the Seattle City

Council in 1937 and was elected to Congress in 1944. The former UW

lecturer was one of the leaders of the Washington Commonwealth

Federation and had close ties with the Communist Party.

Most

historical accounts end in the 1950s. But the CP did not end with the

Cold War. Although much weakened, it still carried on. And as the

decades passed Party members found new opportunities to participate in

the political process. One of the important contributions of this

project is our attention to the post-Cold War experiences of Communists

in Washington State. Their attempts to rebuild their organization proved

unsuccessful, but their participation in causes was often quite

important. Mostly quietly, without identifying their Party affiliation,

members have lent their organizing expertise to projects and causes

ranging from the anti-war, Black Power, and Indian Rights movements of

the 1960s to the revived labor organizations, anti-racism coalitions,

and some of environmentalist causes of the 1990s.

The essays that follow develop this story in chronological order. They rely on a variety of secondary sources as well as some archival collections, newspapers published by the Party and its affiliates, and the interviews that were conducted for this project. One other source will be referenced repeatedly. Eugene Dennett joined the Communist Party in 1931. Twenty-two years old, a schoolteacher, he spent the next sixteen years working for the Party in various mid-level leadership positions mostly in Washington State. Expelled in 1947 for reasons he thought unfair, he testified against his former comrades before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1954. Yet he remained an activist and labor radical for the rest of his life. In the 1980s he began writing an autobiography entitled Agitprop: The Life of a Working-Class Radical. It was published just after his death in 1990. Critical and to some extent bitter about his relationship with the organization he once fully embraced, Dennett's is the most detailed personal account we have of Party activities and organizational issues for the 1930s and 1940s.

Next: Rough Beginnings: The 1920s

[i] Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes, The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself (1992); Klehr, Far Left of Center : The American Radical Left Today (1988); Ronald Radosh, Commies : A Journey Through the Old Left, the New Left and the Leftover Left (2001). See bibliography for fuller list.

[ii] Philip Bart, et al., eds., Highlights of a Fighting History: Sixty Years of the Communist Party USA (1979); Gus Hall, Working Class USA : The Power and the Movement (1987); Gus Hall , The Communist Party USA - Changing, Growing, Swimming in the Mainstream : Report to the National Committee of the Communist Party USA, January 17, 1998

[iii] A few examples: Michael

E. Brown, Randy Martin, Frank Rosengarten, George Snedeker, eds.,New Studies in the Politics and Culture of U.S. Communism (1993);

Robert Cohen, When the Old

Left Was Young: Student Radicals and America's First Mass Student

Movement, 1929-1941 (1993); Maurice Isserman, Which Side Were You On? : The American

Communist Party During the Second World War

(1982); Roger Keeran, The Communist Party and the Auto Workers Unions

(1980); Robbie Lieberman, My

song is my weapon : People's Songs, American Communism, and the

Politics of Culture, 1930-1950 (1989).