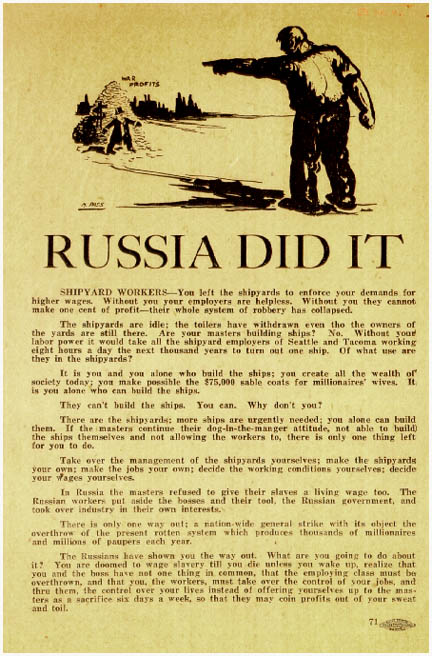

An IWW leaflet produced in Seattle

during the General Strike. Records - Industrial Workers of

the World, Acc. 544, Box 3, UW Libraries. For a larger version of

this image click

here.The rise

of the Washington State Communist Party is part of the story of American

Communism. In 1919 the

Socialist Party of America split apart and gave birth to not one but two

communist parties. Inspired

by the Bolshevik revolution and determined to affiliate with the new

international Communist movement, one group of leftwing Socialists

bolted and established the Communist Party of America (CPA), while

another group of Reds tried to take over the Socialist Party, only to

fail and be expelled. In

September 1919 they established the Communist Labor Party (CLP). The new parties remained separate for almost two years. CPA, led by Charles E. Ruthenberg, was largely comprised of what

had been the foreign-language sections of the old Socialist Party. The

rival Communist Labor Party, led by John Reed and Benjamin Gitlow,

attracted English-speaking radicals. Under pressure from the Communist International (Comintern), the

parties merged in 1921, becoming the Communist Party USA (CPUSA), with

Ruthenberg as leader.

The Pacific Northwest seemed like fertile ground for the new movement. The region had long been recognized as a center of labor radicalism. The Socialist Party of Washington (SPW) had formed in 1901, and by 1912 was strong enough to elect city officials in a number of cities, including Seattle. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) also flourished in the cities and timber camps of the region and succeeded in pushing the rest of the labor movement and many Socialists to the left. Most of those who joined the SPW after 1912 allied with the "Red" (revolutionary) faction. That was especially the case among the Finns and other immigrant groups who maintained their own Socialist locals. Events of 1919 further demonstrated the region's radical potential. In February of that year the city of Seattle was shut down by a general strike that began in the shipyards and soon involved 60,000 workers. As the year progressed, other dramatic strikes spread across the country (e.g., Boston police strike, massive coal and steel industry strikes), creating a revolutionary romantic atmosphere that seemed to bode well for the new movement.

Anna Louise Strong (courtesy Seattle Public Library

and History.link.org)As

elsewhere, both parties were launched in the Northwest and the rivalry

kept either from being very effective. Many of the early members came from the Red wing of the old

Socialist Party. Native-born

radicals tended to join the Communist Labor Party, while the

foreign-born joined the Communist Party of America. Members of the new parties tended to live in urban areas of

Seattle, Tacoma and Portland, although coastal lumber towns like Astoria

and Aberdeen, with their large Finnish and Scandinavian populations,

also contributed.[i]

The Communist Labor Party attracted some well known labor radicals, at least for a time. Hulet Wells, John C. Kennedy, Carl Branin, and others who had been part of the Red faction of the Seattle Socialist Party, tried out the new Party either officially or unofficially. Hulet Wells, who had been a Socialist mayoral candidate in 1913 and was imprisoned during World War I for his anti-war statements, did not stay long in the Party, if he ever joined, but he would work with it through much of the early 1920s. So, too, did Branin and Kennedy, who along with Wells would later run the Seattle Labor College and in the early 1930s would launch the Unemployed Citizens' League. An even more famous early convert was Anna Louise Strong. A settlement house worker turned labor journalist, Strong had served for a time on the Seattle Board of Education before her sympathetic articles about the IWW caused her to lose a recall election. A member of the General Strike Committee and columnist for the Union Record, Strong gained even more notoriety when on the eve of the 1919 strike she penned a front-page editorial that seemed to call for revolution:

There will be many cheering, and there will be some who fear.

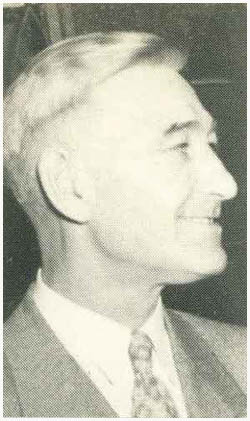

Henry P. "Heine" Huff

joined the Wobblies (IWW) in 1917. He saw and learned from the

Centralia conspiracy struggle while working as a railroad

switchman, and eventually joined the Communist Party on January 1, 1920 as a

Charter Member (courtesy CPUSA

online)Both these emotions are useful, but not too much of either. We are

undertaking the most tremendous move ever made by LABOR in this country, a move which will lead-NO

ONE KNOWS WHERE!

Some of those who joined the two Communist Parties in the early 1920s were former Wobblies. Indeed, the Communists hoped to replace the IWW as the militant voice of the Left and worked hard to recruit in the lumber camps and skid-roads where the IWW had been strong. Henry "Heine" Huff, one of the new recruits, was a railroad switchman who joined the CLP in early 1920 and stayed a Communist for the next forty years. In the 1940s he became District Organizer, the top leadership position for the Party in the Northwest, and in 1953 he was among the eight Washington State Party leaders indicted under the Smith Act.

District organizers were responsible for activities throughout their districts, such as forming nuclei among factory workers, conducting political campaigns, arranging mass demonstrations, circulating literature and raising funds for the Party. Following the merger of the two rivals in 1921, the Party organization was divided into twenty districts. Washington and Oregon were the 12th District, headquartered in Seattle. Sidney Bloomfield was the first District Organizer.[ii]

The two communist factions did not immediately change the form of organization inherited from the Socialist Party in 1919, which had rested on the assumption that the working class would become the majority and parliamentary activity would be the means to educate the workers about the need for socialism and a path to power. The Communist Party of America did add shop nuclei (branches based upon the place of work) to the geographical branches (districts), but, even after the merger, the organization of the CPUSA essentially remained the same as the old Socialist Party. However, after 1924 efforts were made to "Bolshevize" the Party. This meant a move away from electoral politics and a shift into the factories and unions to obtain closer contact with workers in major industries.[iii]

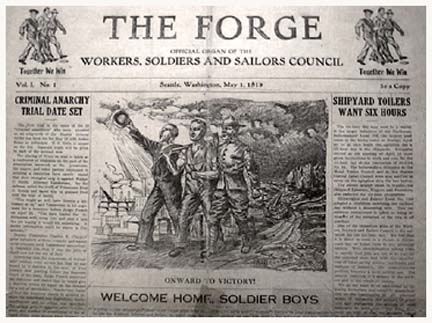

The Workers, Soldiers, and Sailors

Council (WSSC) was formed in Seattle and began publishing The Forge

in early 1919. With links to the One Big Union movement, WSSC

was one of a number of revolutionary organizations competing with

the new Communist Parties in the Pacific Northwest.It is

hard to gauge membership figures for the 1920s. People moved in and out of the movement and it is doubtful that

at any given time more than a few hundred members were to be found in

Washington State. A

Congressional committee investigating Communist activities estimated

12,000 paying members nationwide in 1930. George David Hanrahan. a Washington State Party member, estimated

there were 300 to 500 members in Seattle, but he did not have a sense of

how many there were statewide. Seattle

Police Chief Louis Forbes thought the number in the Seattle area might

be 500, and added that about half were "foreign stock," mostly Finns

and Russians.[iv]

The Twenties were a chaotic period for the CPUSA and fellow-travelers around the nation. During the Red Scare that lasted from 1919 and 1921, local, state and federal agents detained hundreds of Communists for advocating violent revolution and many were deported. Although neither Communist Party (before the merger) was outlawed and Party membership by an American citizen was not a crime, non-citizens could be deported. Federal immigration officials deported nearly a thousand alien radicals during this era. Communists were forced to go underground using pseudonyms, changing residence, and dividing into small cells that met in secret locations. These activities were necessary to protect non-American citizens and to avoid expulsion from labor unions and other organizations that prevented Communist Party members from joining.[v]

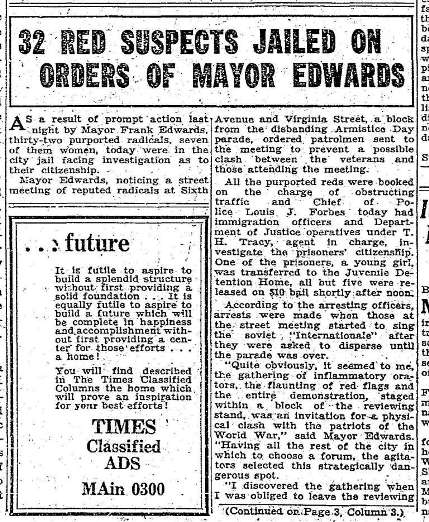

Arbitrary roundups of Communists and IWWs continued into the early 1930s. In this Seattle Times article from Nov 12, 1929, the newspaper supports Mayor Edwards' decision to arrest peaceful demonstrators.In

Washington the new communist parties were caught up in the wholesale

persecution of IWW members and other radicals following the November

1919 Centralia massacre. Local and state authorities joined federal

agents in rounding up suspected Reds. Business groups joined in. The

Associated Industries of Seattle led a spirited campaign in 1919 and

1920 to subvert the labor movement, using agents to infiltrate and

gather information on the IWW and the AFL-affiliated Seattle Central Labor Council (SCLC). An example of this was a sixteen-page pamphlet entitled Revolution,

Wholesale Strikes, Boycotts: Two

Years of Attacks on Seattle's Business and Industrial Institutions by

a Certain Radical Element, published about 1920, which spoke against

the boycott of Seattle businesses then being effected by organized

labor. The pamphlet also

argued that Seattle was one of the three major centers of radicalism

nationally and that extraordinary efforts and vigilance were necessary

to meet the crisis.[vi]

To minimize their exposure, the united Communists adapted the name The Workers' Party (WP). Even with these measures, Communists were still being arrested and deported. For example, a November 12, 1929, article in the Seattle Times reported the arrest of several Reds "to prevent a possible clash between the veterans (on Armistice Day) and those attending the (Communist) meeting" and that "arrests were made when those at the street meeting started to sing the Soviet 'Internationale' after they were asked to disperse until the parade was over." The strong sentiment against the Communists was made clear by Mayor Frank Edwards:

I will tolerate no inciting of riots, no demonstrations against our government, no raising of the red flag of anarchy or any other move to destroy the peace and tranquility of our citizens and to make a mockery of the rights of peaceful assembly and free speeches guaranteed by our constitution. These people do not attempt to avail themselves of the constitutional guarantees; they deride them, mock at them, use a pretense of privileges for wanton license of disorder. That we cannot tolerate —not in Seattle.[vii]

The Party picked up where many of the dissolved radical groups left off in trying to become a powerful independent force, at the same time joining up with other labor organizations to influence them. Following along the lines of the old Socialist Party, the main goal of the Communists, particularly in Washington State, was to influence and dominate the labor unions and other organizations, hoping to eventually move the broader labor movement toward Communism through education and inside politics. One of the first targets was the Union Record, owned by the Seattle Central Labor Council and the only labor-owned English-language daily newspaper in America. Joining with IWWs and other Reds, Communists attacked the editor, Henry B. Ault, as a "labor capitalist." Ault fought back, supported by most of the SCLC. "We will fight to the ultimate limit every attempt to turn this paper to either the IWW or the Communist Party," he editorialized.[viii] The radicals then formed a sixteen-member "Committee of 100"to rally radical support against Ault and labor-capitalists. They set up a weekly newsletter called Save the Record wherein they attacked the Record leadership, mailing editions to AFL members. The Union Record published its own newsletter to discredit the radicals.[ix] In the end, the radicals lost, but the fight had taken a toll on the labor movement as a whole. In a sense it was a small victory for the Left since it showed that Communists could have some leverage.

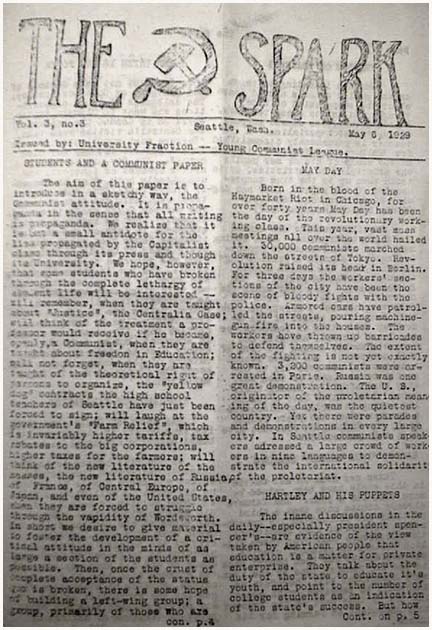

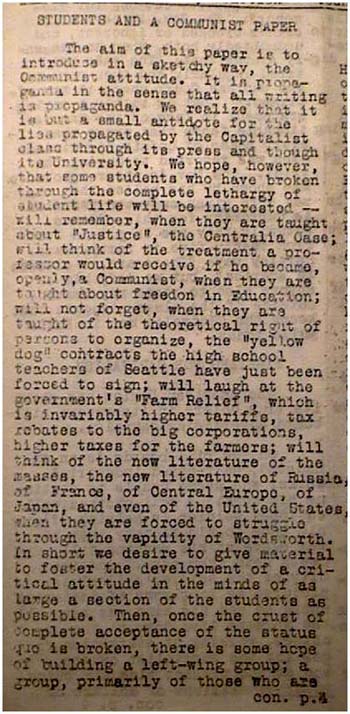

The Spark, published by the Young Communist League, University of Washington Chapter, 1929. One surviving copy is in the UW Manuscripts, Special Collections LibraryThe new

movement also had an impact on labor-oriented electoral politics. In

1920 much of organized labor had joined with the powerful Grange

organization to create the Farmer-Labor Party of Washington, which

gained 77,246 votes in that year's Presidential contest. Communists

joined the coalition and were soon using their positions to influence

policy. By 1922 the Workers

Party (Communists) was in a position to be recognized as a political

force within the Farmer-Labor Party (FLP) and in the related Seattle

Labor Party (SLP). The Mark

Litchman papers indicate that the coalition of FLP/WP/SLP agreed to

united actions but little else.[x] The WP demanded numerous political concessions in exchange for

political cooperation, but the FLP refused. A fight ensued that damaged the Farmer-Labor Party and its

electoral chances. The Reds

had some influence with the delegates from the Seattle Central Labor

Council and still more with the Tacoma Labor Council. When, just before

the 1922 election, the Workers Party broke with the FLP, the Tacoma

Labor Council endorsed the Communist candidates. It was an empty

gesture. Franz Bostrom, Workers Party candidate for the US Senate,

received only 489 official votes that year. James Duncan, the Farmer

Labor candidate tally was 35,352, but the real message was that the

infighting had damaged the promising third party movement.[xi]

And the days when Communists could openly participate in such coalitions were drawing to a close. From the onset, the WP had no direct control over any labor council nor was its membership in the councils large enough in numbers or in key positions to significantly change policy. It must also be emphasized that the majority of radical labor activity was not conducted by the Party alone but by unofficial communists, sympathizers, fellow-travelers and by other radical organizations like the IWW that shared certain leftwing beliefs with the Party.

The Workers Party in Washington State was starting to lose its grip just as it had begun to settle in. The American Federation of Labor (AFL) had long felt that the Seattle Central Labor Council was too radical. In 1923 it moved to do something about it, ordering the SCLC to stop cooperating with Communists and other radicals. On April 10, 1923, the AFL executive council charged that the SCLC had placed non-labor issues, such as recognition of the Soviet Union, ahead of its "legitimate" trade union interest, that it had defied the AFL's non-partisan political policy, and that it had recognized and seated delegates from suspended unions and dual labor organizations, namely the IWW and the Workers Party. It gave the SCLC an ultimatum to submit to AFL government or face revocation of its charter.[xii]

The AFL initiative strengthened the hand of conservative trade unionists but did not accomplish its full purpose . Two years would pass before the Reds were completely expelled. By 1925, the issue of labor radicalism simmered near the boiling point. Radical influence had declined in the SCLS, but Communists were still a presence and had kept up a steady campaign of criticism of the conservative leadership. The battle erupted in January 1925 when a radical delegate to the SCLC tried to grant the floor to Norman Tallantire, a Workers Party member who planned to ask the SCLC to endorse a fund drive to release a number of Communists from prison. This was a tactic used by the Left faction to publicly embarrass the leadership. A conservative delegate made a motion to deny Tallantine's request, thus precipitating an uproar. Later, the Daily Worker described the events under the headline, "SLAMMED THE FAKERS":

He was followed by other reactionaries, who urged that the floor not be granted to Tallantire. In turn the Communist delegates let (sic) by Paul Mohr, Havel, Jones, and others landed heavily on the reactionaries, the result being a vote of 45 to 36 in favor of granting the floor.[xiii]

The Spark, published by the Young Communist League, University of Washington Chapter, 1929. One surviving copy is in the UW Manuscripts, Special Collections LibraryThe conservative

leadership did not let the event go unpunished. On February 3rd the Seattle Building Trades Council

requested the SCLC to unseat all its Communist delegates and "live up

to the principles and policies and the parent body," on the grounds

that the AFL was "definitely on record against Communism and

communists" and had revoked the credentials of William Dunn at its

Portland convention when Dunn admitted to being a Communist.[xiv]

The SCLC was flooded with letters supporting the move against Communists, and, accordingly, filed charges against Mohr, Havel, Jones, and several SCLC delegates, including H.G. Price, M. Hansen, and J.C. Carlson, who had participated in the debate. At the same time the SCLC leadership requested support from the AFL. President William Green informed the SCLC that it was:

clearly within its rights in declaring a delegate ineligible to represent organized labor provided such a delegate is duly and legally charged with being a Communist and after a fair trial is found guilty. Any delegate so charged may appeal from the action (to the AFL). [xv]

The chief evidence against him was the Daily Worker article of February 17, 1925. Mohr responded to the charges by claiming that the AFL of undermining the labor movement. [xvi]

On March 18th the committee made its preliminary report to the SCLC, with radicals of every kind packing the galleries. The next week the debate on the committee's report began with SCLC President John Jepsen closing the galleries on the grounds that radicals at the previous meeting failed to show any respect by delaying proceedings. The SCLC sustained his motion by a vote of sixty-eight to forty-five. The report indicated that Mohr had considered himself a trade unionist first before being a Communist and that his brand of Communism was not in "accord with what the committee believes to be Communism as understood by the AFL. We therefore recommend that the charges be 'not sustained.'" But the SCLC leadership ignored the report and demanded that Mohr be expelled along with the other five. The Council vote was close. Seventy-eight delegates voted for expulsion; while seventy-one opposed, which came as a surprise. Apparently many delegates sympathized with Mohr.[xvii]

The conservatives were backed up President Green, who sent a letter to Jepsen sustaining the council's decision in unseating the Communists. Still, the expelled Reds did not give up and they showed up at SCLC meetings with credentials from various locals asking to be seated as delegates. Always they were refused. In July 1925 a notice was put out, regarding the unseated delegates:

. . . owing to the repeated efforts on the part of some unions to have reseated delegates that have been expelled from the council, Brother Jepsen made it very clear in a statement he made to the members that the matter was out of the jurisdiction of council and these members only redress was the (AFL's) executive Council and in future secretary stand instructed if any more credentials come in for these members to immediately notify their respective local of the council's action. His remarks meet (sic) with the hearty approval of most of the delegates present...[xviii]

This finally put an end to the long conflict between the Left and Right in the SCLC. This also ended Communist Party hopes to influence the AFL-based labor movement. Party members continued to seek re-admittance to the SCLC as late as 1933 and were denied every time. The SCLC's position was best summarized by Harry Call, the acting secretary of the Washington State Federation of Labor, in an article entitled "Communism a Menace," which appeared in the Washington State Labor News 1925 Yearbook. Communism was a "menace," he wrote, because the dictatorship of the working classes is "just as undesirable and just as un-American as would be dictatorship of the middle classes or groups, or a dictatorship of capital." The use of force cannot cure the "ills of industry." Communism was a movement for "destruction," as opposed to "construction." Call believed that the AFL was the best hope for labor and that labor should follow the teachings of Christ and reject the "lying effrontery" of communism." [xix]

By the late 1920s the failures of the Communist movement were very apparent. The 1927 annual report of the Washington Unit of the American Civil Liberties Union stated, "The reason for the decrease in repression is that there is little to repress. Militancy in the labor movement has declined; the radical movements do not arouse fear. Insurgence of any sort is at a minimum." The report concluded that "[N]o new repressive laws have been passed, probably for the simple reason that it would be difficult to suggest any."[xx]

Moves were made in several states in the following year to keep the Workers Party off the ballot. In Washington, Secretary of State J. Grant Hinkle ruled that the party was ineligible for a place on the ballot. However, the State Supreme Court overturned this ruling. The Communists hoped that the court victory and publicity would help their electoral campaign and they put forth candidates for several state offices, as well as promoting Party Chairman

William Z. Foster's Presidential campaign. The results were a clear indication of the Party's limited popularity in Washington State: Foster received 1,541 votes. Alex Noral, running for Senator, and Aaron Fislerman, candidate for Governor, gained 666 and 698 respectively. [xxi]

Still, the 1920s had laid the groundwork for what was to come. Even before the Great Depression struck, the Party was showing signs of renewed energy in the Pacific Northwest. A new group of organizers had emerged, including Noral, who would become District Organizer in 1931, and Fred Walker, assigned to breathe life into the District's Young Communist League (YCL) As 1929 dawned, Communists were once again active. Organizers were trying to build a new union of timber workers in camps and mill towns near Grays Harbor. Soap-boxers were appearing nightly on the streets of Seattle's skid-road, their meetings inevitably broken up by police. And on the campus of the University of Washington a small YCL group had reformed and were putting out a sprightly little newsletter called The Spark.

© 2002 Daeha Ko

Next: Organizing the Unemployed: The Early 1930s

[i]Jonathan Dembo, Unions and Politics in Washington State 1885-1935 (New York: Garland Publishing, 1983), 92.

[ii]US Congress, House. Investigation of communist propaganda. Hearings ... pursuant to H. Res. 220, providing for an investigation of communist propaganda in the United States. Part 5, volume no. 1, Seattle, Wash., October 3, 1930, Portland, Oreg., October 4, 1930 (Wash. D.C.,1931) , 14

[iii]James Weinstein, Ambiguous Legacy: The Left in American Politics (New York: New Viewpoints, 1975) , 37-38/

[iv]US Congress, House. Investigation of communist propaganda. Hearings, 45

[v] Harvey Klehr, The Secret World of American Communism. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 7-9.

[vi]Albert F Gunns, Civil Liberties and Crisis: The Status of Civil Liberties in the Pacific Northwest, 1917-1940. (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Washington, 1971), 95. See also copy in Litchman Collection, Box 1/7 and William M. Short, History of Activities of Seattle Labor Movement and Conspiracy of Employers to Destroy It and Attempted Suppression of Labor's Daily Newspaper, the Seattle Union Record (Seattle, n.d.); Xerox copy in William M. Short Collection, Special Collections, UW.

[vii]Red Suspects Jailed on Orders of Mayor Edwards,."Seattle Times, 12 November 1929.

[viii]Dembo. Ibid.

[ix]Loc.

cit.

[x]Ibid., 345. See also Cravens, 160; Union Record 4 May 1922; Litchman to Slater, 25 May 1922, Litchman Papers.

[xi]Washington Secretary of State, Abstract of Votes 1922; Dembo, , 346-347.

[xii]Ibid., 363.

[xiii]Daily Worker 17 Feb. 1925; Paul Mohr Trial Transcript. 1925; G.W. Roberge to C.W. Doyle, 3 Feb. 1925, Box 6; J.N. Belanger, et al. to Building Trades Council, 13 Feb. 1925, KCCLC Records, Box 6..

[xiv]Ibid.

[xv]Minutes, 4, 11, 18-25 Feb., 4, 18 March 25, Box 8; Freen to C.W. Doyle, 6 Feb. 1925; Report of Strike and Grievance Committee of the Trials of Delegate Price, Hansen, Carlson, Mohr, Havel, and Jones, 18 March 1925, KCCLC Records, Box 6..

[xvi]Ibid..

[xvii]Dembo, 420-421

[xviii]Minutes, 1 April 1925, KCCLC Records, Box 8. Minutes, 8, 15 April, 13 May, 8 July, 12 Aug. 1925; 12, 26 Jan., 27 July, 17 Aug. 1927; 2 Aug. 1933, Box 8; Resolution, 15 Jan. 1929, KCCLC Records, Box 6.

[xix]Washington State Labor News 1925 Yearbook.

[xx]Gunns, 95-96

[xxi] Washington Secretary of State, Abstract of Votes 1928