More than 1,100 delegates attend 1940 Seattle convention of the Washington Commonwealth Federation. The WCF nominated candidates for state and local offices, functioning as a leftwing caucus within the Democratic Party. (February 8, 1940)Imagine

the difficulties of today trying to organize such disparate groups as

welfare mothers, members of Democratic Party clubs, AFL-affiliated

members, militant radicals, civil rights activists, liberals and labor

unionists. Yet, that is

what two politically-left organizations accomplished in Washington State

during the 1930s and 1940s. The Washington Commonwealth Federation (WCF)

and the Washington Pension Union (WPU) were broadly successful political

organizations with tens of thousands of members and a great deal of influence. For the better part of a decade they mobilized a broad coalition of progressive Washington State residents into a political caucus that could at times dominate the state Democratic Party. And they used that power to re-write laws and social policy. By the end of the 1930s Washington State had some of the most liberal and comprehensive pension and welfare policies in the nation.

Members of the Communist Party played a central role in both the Washington Commonwealth Federation and the Washington Pension Union. Although neither had been founded by the Party, by the late 1930s Party members were in key positions and mostly able to control these mass organizations with their broad spectrum of activists and supporters behind initiatives, candidates, and issues that advocated a diverse reform agenda. The Party's influential position reflected an important shift in strategy away from advocacy of immediate revolution towards building Popular-Front relationships with reformist organizations. Communists used the Popular-Front strategy after 1935 to broaden the base of the Party and build left coalitions. That year, the Comintern declared that the first priority of the Communist Parties everywhere was stopping the rise of fascism, and the way to do that was to join with other progressive forces. Paul Buhle

680 delegates attend the first convention of the Washington Old Age Pension Union. Within a few years the WPU will claim to have 30,000 members. James Sullivan, Speaker of State House of Representatives, is elected president. He will later testify that Communists forced him out of the WPU leadership. (November 13, 1937)and Dan Georgakas note in the Encyclopedia of the American Left the implications of the Popular-Front orientation for the CP: “This policy entailed a strategic reorientation of major proportions. The communists would work within non-Left, mass institutions, including the AFL and labor or labor-farmer parties.”[i]

There was great opportunity in the strategy, but also tension. Communists had to consider what it would take to keep these coalitions and their supporters interested in their issues and then how to integrate these concerns into Party strategy. During this time the Communist Party worked very hard to balance the institutional pull of reformist proposals that would speak to the broadest number of people with a core ideological belief in the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism.

Opponents of WCF and WPU denounced the organizations as “Communist fronts.” They were said to be nothing more than pawns or agents following orders of their puppet masters in the Soviet Union. Detractors used the label “Communist front” or “front group” with more and more frequency, especially as momentum developed behind their initiatives. Until the WCF and WPU dissolved, even dissenters within PF organizations agreed that Communists were an important influence on the left wing of the Democratic Party, and sometimes on public opinion. Perhaps the greatest source of strength of the PFers as Washington Governor Arthur Langlie noted, was that they worked “tirelessly for their issues.” Regardless of how their detractors labeled them, Communists and Popular Front organizations contributed to the passing of significant social policy for Washington state residents beginning in the 1930s that remain with us today.

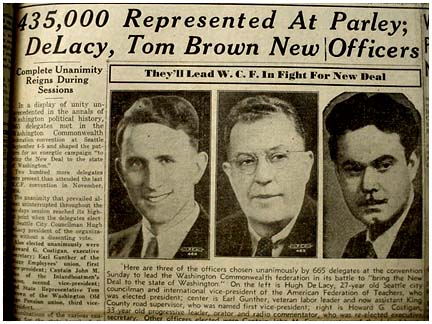

Officers of the Washington Commonwealth Federation in 1937: Hugh DeLacy (President - L); Earl Gunther (V.P. - C); Howard Costigan (Executive Director - R). Sunday News September 11, 1937Groups that formed the WCF in 1936 included the Grange, United Producers, the Liberty Party, Bellamy Clubs, Continental Committee Technocrats, Democratic Party Clubs, Commonwealth Builders, reformers, liberals, trade unionists, and Communists Through the late 1930s and 1940s people known to be members of the Communist Party were WCF-supported candidates for the Seattle City Council and Washington State Legislature. Among the Communists elected to office were Hugh DeLacy, Kathryn Fogg, H.C. Armstrong, N.P. Atkinson, and Lenus Westman. Historian Albert Acena, who authored the major study of the Washington Commonwealth Federation, described the organization as “one of the most successful political efforts of the Communist Party in the New Deal Period.”[ii]

The WCF flourished from 1935 to 1945. It grew out of an earlier organization, the Commonwealth Builders. The Commonwealth Builders had connections to Upton Sinclair’s End Poverty in California movement. In 1934 Sinclair ran for governor in that state on a platform of “production for use.” That phrase aptly summarizes the program of the Commonwealth Builders, which promoted the idea that the state should buy the land or factories that had gone bankrupt and utilize the acquisitions to employ able-bodied people now out of work. In 1934 the Commonwealth Builders managed to elect a block of new legislators pledged to embrace liberal and progressive causes.

In 1935 the Commonwealth Builders enlarged its reach by renaming itself the Commonwealth

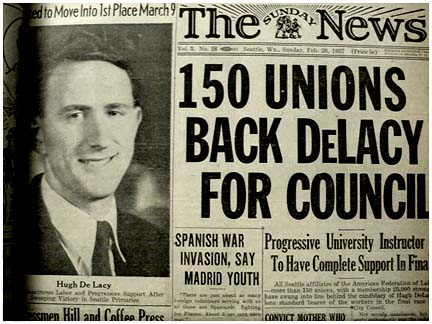

A 27 year-old teaching assistant in the UW English Department, Hugh DeLacy wins election to the Seattle City Council in 1937 as the Washington Commonwealth Federation candidate. In 1944 he wins election to Congress. (February 28, 1937)Federation. The new Federation aimed to broaden its base through affiliation with other progressive groups, with one exception: it continued to exclude Communists. Despite their formal exclusion, CP activists demanded admission. They envisioned the WCF as a crucial component of what might evolve at some point in the future into a genuinely revolutionary movement. In 1936, members of the Communist Party went to the WCF convention as uninvited guests. Over time, individual Communists won acceptance by volunteering time and services to advance WCF causes. Communists frequently chaired committees, ran for office, and eventually even assumed WCF leadership positions.

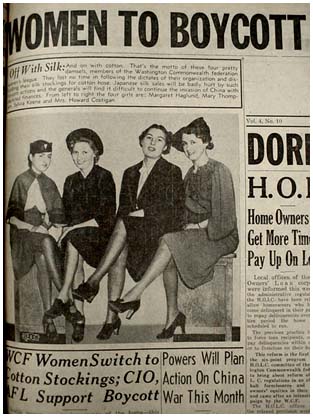

Like its predecessor, the WCF was a political organization that functioned inside the Democratic Party, nominating left-wing Democrats for office. One of the organization’s key assets was its weekly newspaper which changed names repeatedly over the course of several years. Starting as the Commonwealth Builder, it became the Commonwealth News in 1935, the Sunday News in 1936, the Washington New Dealer in 1940, and the New World in 1943. Party members Howard Costigan and Terry Pettus edited the WCF newspapers from 1936 until the New World folded in 1948.

The WCF Preamble and Platform adopted on November 26, 1938, at the State Convention, reflected the organization’s perspective on the economic and social issues of the day, but was framed in terms that a broad majority of people could relate to through reference to world events. The Preamble begins:

The people of the United States have a proud heritage of democracy and an undying hope for social justice and economic well-being. Today powerful and sinister forces living by special privilege threaten this American heritage. Enemies of democracy within are linked in spirit and program with fascist allies abroad who are waging aggressive wars against all democracies and threatening the peace of the world.

Our state of Washington has yet to carry out on a state scale the spirit and principles of the national New Deal program. The work already done needs to be improved and the problems yet untouched, solved, if we are to make our democracy continue to live and work. [iii]

The WCF’s diverse reform proposals encompassed measures that were both broad and tangible, including Social Security, public ownership policies (natural resources, public utilities and natural monopolies and public control of national credit), labor rights, farm policies, public housing, public health, consumer protection, the needs of independent business, education, youth, progressive taxation, and international relations (an endorsement of the New Deal’s “Good Neighbor” policy toward Latin America).

Once accepted as WCF members, the Communists embraced the Commonwealth Federation program while still managing to rhetorically criticize the apparent failures of the capitalist economic system. At one point the WCF even proposed a very radical “Production for Use” bill in the Washington Legislature. When the Legislature failed to pass the bill, WCF activists gathered enough signatures to place the measure on the 1936 General Election ballot as Initiative 119. Many historians argue that the defeat of the “Production for Use” initiative signifies the final effort by Communists in the WCF to enact genuinely radical proposals. Henceforth, CP-sponsored efforts were limited to more modest proposals—all of which had reform of the current system as their focus, including pensions, a graduated state income tax, public power, benefits for the unemployed, and public health issues.

Public health became a vehicle for the WCF to appeal to the general public and build support. The Washington Commonwealth Federation newspapers devoted considerable space to health and nutrition. For example, an article entitled “Diet Given for Family of Five” delineates exactly what constituted an adequate diet for families with a minimal amount of money to spend on food and even specified precise servings of milk, fruits, vegetables, breads, fats, sugars, and meats.[iv]

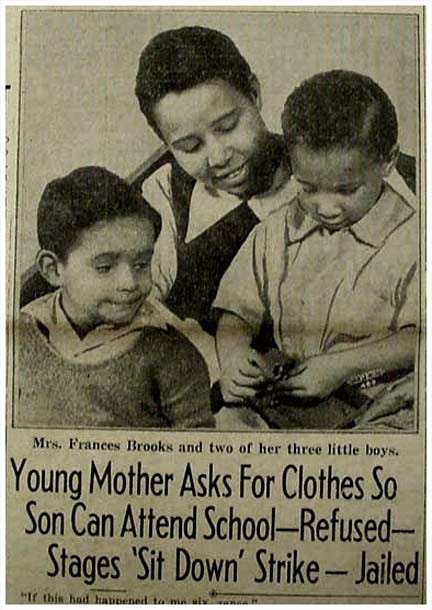

Mrs. Francis Brooks became a relief-struggle celebrity after losing her job with the Negro Federal Theatre Project as a result of funding cutbacks. Arrested for her relief office "sit down strike," she received an outpouring of sympathy. A delegation of 26 women from the Washington Commonwealth Federation attended her court hearing. Sunday News February 14, 1937Other techniques of public-health education were employed by WCF leader and secret Party member Hugh DeLacy, who organized meetings around public-health issues while a member of the Seattle City Council. His remarks in a health-related meeting in September 1939 closely echoed a recent U.S. Public Health Service Milk Sanitation Survey. The statistics he sent to the President of the Parent Teachers Association indicated his close connection with important New Deal officials: the United States Public Health Service rated Seattle’s milk supply at 74% for raw milk, 55.8% for pasteurized milk, and 55% for pasteurizing plants. He noted the USPHS regarded 90% to be the standard under which consumers could feel reasonably well protected.

Even though the WCF concentrated primarily on reformist ideas and proposals after 1936, its effect on politics in Washington State should not be underestimated. The legacy of the WCF can be found in several different outcomes. The first of these is the remarkable fact that Washington voters elected Communist popular-front members (running as Democrats) to the state legislature. In their role as representatives, Communists constituted a clearly identifiable segment on the left wing of the Democratic Party. Through such a solid institutional base they functioned as a very strong and visible political pressure group. The WCF also promoted racial justice, highlighting the case of The Scottsboro Boys. The only exception to what was generally a progressive influence in the state was the unfortunate stand of both WCF and Communist Party in advocating the relocation of the Japanese-Americans residents of Washington to internment camps during the Second World War.

The Washington Pension Union was an outgrowth of the WCF. Founded in 1937 by Howard Costigan and other WCF activists, it outlasted the parent organization which folded in 1945. But well before then the WPU had become the most important Popular Front organization in the state. One of a number of organizations that sprang up to represent the interests of senior citizens after the Social Security Act passed in 1935, the WPU was different from the Townsend clubs and most others in trying to create an actual union to fight for improved pensions. The WPU also advocated a number of other social policy issues in addition to Old Age Pensions, seeking to raise public awareness on general assistance grants and aid-to-dependent children program. Historian Margaret Miller’s, The Left’s Turn: Labor, Welfare, Politics and Social Movements in Washington State is the best source on the WPU.[v]

Groups that formed the WPU included Aid-to-Dependent-Children mothers, labor unionists, timber workers, civil rights activists, pensioners, peace activists, and Communists. By the late 1930s the WPU claimed to have a membership in excess of 30,000,

WPU members present initiative 172 petition and 145,841 signatures. MSCU University of Washington Libraries (Washington Pension Union papers, accession 185-1, folder 7/4).probably an exaggeration. But in the 1940s it was powerful enough to win some very important electoral victories including initiative measures that liberalized state pension programs. It also helped elected Communists to political office, including William Pennock, Emma Taylor, and Tom Rabbit.

The WPU Resolution on Old Age Pensions, in part, at least, inspired by popular- front Communists, roused those on the liberal left as well as the general public with its inspiring language. The Resolution began:

The present paradox of a paltry old age pittance is being reluctantly administered to the aged people of this state by a heartless administration even though unbiased pools of the voters of the state show a majority of our citizens favor a more adequate old age pension of $60 a month for every one over 60 in need in this state.[vi]

Pensions seemed to be a natural issue for popular-front organizing efforts as the need to begin paying them seemed to be universally accepted even among white collar and educated Americans.

William Pennock became President of the WPU and presided over it during its years of greatest influence. One of a number of secret Communists to gain prominence in Washington state, he also served in the state legislature. A chief target of the red hunters, he was indicted in 1952 under the Smith Act but took his own life before the trial concluded.Older workers in the 1930s were frequently the first to be fired, the last to be hired. There is no question but that they were the most vulnerable population during the Great Depression. From 1920 to 1930 Washington State had the fastest growing elderly population in the nation. The Constitution of the WPU sometimes reflected the strident rhetoric of the time, evoking nationalist sentiment for the war against the Fascists. In this regard the WPU preamble declared:

We, the members of the Washington Pension Union, subscribe to the following propositions: 1. Victory in our just, Peoples’ War against the Hitlerite Barbarians is the only guarantee of freedom from wants and other freedoms. 2. Victory can be won only by the mobilization of the entire human resources of our country. To this end a war-time pension program must provide for the maximum participation of all senior citizens in the offensive on the home front. 3. To win victory and insure a just and lasting peace, we must fight on all fronts.[vii]

The WPU adopted an organizational structure like that of a union or political party, composed of locals, county councils, a state board and an executive committee. Strategically, the WPU used ties to the Democratic Party and organized labor to advocate for social welfare policies. As WPU members, Communists became active in Democratic Party precinct and district committees. They sought to use the legal system and state government to discredit Republican administrations and to enact progressive reform. This was demonstrated especially in the 1940s when they built support for political candidacies, largely in the Democratic Party, and used initiative campaigns to liberalize public assistance. Communists used the initiative process not only to set state policy, but also to educate and involve voters.[viii]

In the 1940s the WPU gained momentum at least partially due to the optimism and energy of William Pennock, and soon surpassed WCF membership totals. This may have been due to the popularity of pensions and active support for the war after Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Popular-front politics at this time meant diversifying constituencies to include African Americans and women, although the WPU was not considered inherently egalitarian. The Union was, however, flexible enough to accommodate female activists.[ix]

The work of the WPU led to reform and social policy unprecedented for its time. By 1949 Washington State claimed the third-highest Old Age Assistance grants in the nation, the second-highest General Assistance, and the highest payments for Aid to Dependent Children, The Pension Union’s measures also received two-to-three times the number of required signatures to get on the ballot, and once on the ballot earned hundreds of thousands of votes. In a very practical way, then, WPU’s ideas and strategies spoke to people in this state. Perhaps most important of all, for left and liberal activists, the WPU functioned as a stepping-stone for the politically ambitious.

The WPU was one of the chief targets of the Canwell Committee hearings. In this image, State Patrol officers eject E.L. Pettus, vice president of the Washington Pension Union, after Pettus stood up and protested the constitutionality of the hearings. Courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry, Seattle, Washington (Seattle Post-Intelligencer collection, no negative number [filed under E.L. Pettus, 3/26/48]).Through the WCF and WPU the Communists used the popular-front strategy to challenge, and, in some instances, reform and soften some of the harshest aspects of the economic system. Communists sought to organize large coalitions of people from the liberal left who also challenged the system during the Great Depression. They employed the political process in a multi-faceted strategy to advocate reforms that included seeking elective office, circulating petitions for the initiative process, holding both elective and appointed positions in the Democratic Party, and working closely with organized labor. The inherent tension in this strategy for both organizations was that the more the Communists reached out to liberals and reformers, the more reformist their program became. Nowhere could this be seen more clearly than in the WPU. In 1935 the Communists repudiated the Social Security Act, denouncing it as a liberal reform. Yet this “reformist palliative” soon became the staging area for the popular-front reform politics of the late 1930s and 1940s.

© copyright Jennifer Phipps 2002

Next: Race and Civil Rights: The '30s & '40s

[i]Mari Jo Buhle, Paul Buhle and Dan Georgakas, eds., Encyclopedia of the American Left (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 147.

[ii]Albert Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation: Reform Politics and the Popular Front (Seattle: University of Washington Dissertation, 1975), iv

[iii]Robert Burke Papers, Accession 2948, University of Washington Special Collections.

[iv]Commonwealth Builder, 8 December 1934. Microfilm A4102, University of Washington Library.

[v]Margaret Miller, The Left’s Turn: Labor, Welfare, Politics and Social Movements in Washington State,1937-1973. (Seattle: University of Washington Ph.D. Thesis, 2000)

[vi]Robert Burke Papers.

[vii]Ibid.

[viii]Miller,

[ix]Ibid.,