The Voice of Action helped publicize the Ted Jordan case in 1933. Sentenced to death by an Oregon court, International Labor Defense protests helped save his life. (September 11, 1933)Not even the slightest degree of oppression, or the slightest injustice in respect of a national minority- such are the principles of working class democracy.”[i]

The Communist Party taught that a racially-divided society and work force benefited only the elite, since people of color were employed as strikebreakers during the great strikes before and after World War I, including the general strike of 1919 in Seattle. In the 1920s the Party began actively working within the community to change the conditions of workers of color, and broadened this activism in the decades that

followed. While Communist did not believe racism could be ended completely without the end of capitalism, they did believe that changes could occur that would help move society towards a more egalitarian structure. Stressing the common struggle for all workers against an unfair economic system, the Party tried to break the pattern of white supremacy that had long plagued the American labor movement. [ii]

The Communist Party’s civil rights activities came at a time of racial antagonism.

Voice of Action November 13, 1933Washington State experienced a rapid growth in its communities of color when many people came to the Pacific Northwest during World War I for jobs on the waterfront and in the steel industry. At that time non-whites were barred from most unions, had considerably lower pay scales, almost twice the unemployment rate, and were frequently abused on the job. With no union protection and a racially hostile environment, African-Americans, Japanese-Americans, and other Asians, were easily exploited. [iii]

Racial tensions in the 1920s were coming to a head in the area. A huge Ku Klux Klan rally was held in Issaquah, Washington, in 1924; reports state that anywhere from 13,000 to 55,000 attended. All of this activity, backed by federal and state legislation that was expressly anti-immigrant and anti-person of color, was the context in which the Communist Party of Washington State began working on issues of racism.

Although the Communist Party had consistently adopted tenets intended to be anti-racist, integration was not necessarily the goal. Initially the Party had advocated a separate state for African Americans, calling for complete self-determination in the “Black Belt” region of the South where African-Americans comprised a near majority of the population. This proved to be an unpopular goal for both blacks and whites, and later the CP moved away from the notion of black self-determination.

Most people of color were understandably wary of the Communist Party. Shadowed by the experience of racist unions, the CP of Washington State had to overcome the racist attitudes of the white community while struggling to win the trust of the communities of color. The Party fought these barriers with a program of progressive action, recruiting leaders of color, as well as rank-and file workers.

Voice of Action August 7, 1933The Communist Party’s official platform was to end capitalism and to eradicate ‘chauvinism’ that was directed at women and people of color. [iv]

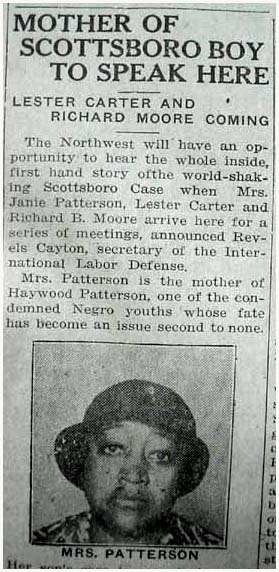

In the 1930s the Party helped publicize the Scottsboro Boys rape case. In 1931, nine young African American men were charged with the rape of two white women in Scottsboro, Alabama. The men were charged, tried, and sentenced to death for the crimes. The case was based on false testimony and the men were essentially convicted because of their race. The International Labor Defense, the legal organization of the Communist Party, was involved in the multiple appeals of the case. The Young Communist League of Seattle (YCL) published and distributed several pamphlets to raise awareness of the denial of equal justice to African Americans. The legal involvement of the Communist Party and the growing national pressure led to the original verdict being overturned in 1934. But then the defendants were convicted again. [v]

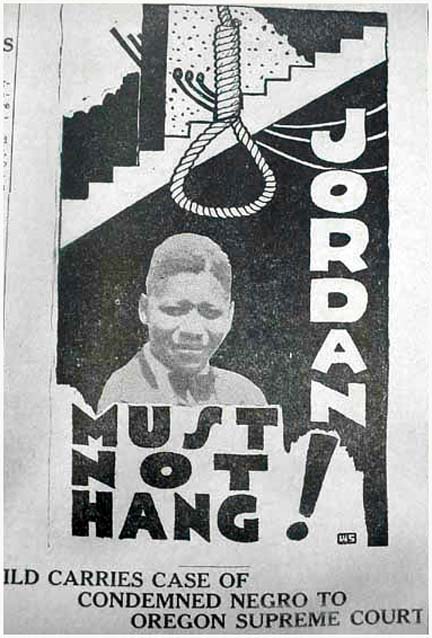

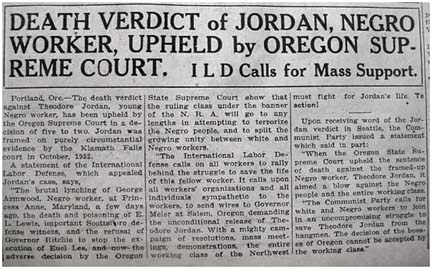

Communists in Seattle used their newspaper, the Voice of Action, as a tool to uncover similar cases and publicize the plight of people of color nationally as well as regionally. In 1933 the paper published a series of articles about a similar court case where a black man had been wrongly accused of murdering a white railroad conductor in Portland, Oregon, and sentenced to death. This, the Ted Jordan case, attracted regional attention thanks to the publicity provided by the paper. The Party’s legal defense organization was responsible for the appeal processes. Led by Revels Cayton, an African-American Communist, a delegation of over 200 people marched on the capitol in Salem, Oregon, demanding that Ted Jordan’s sentence be converted to life in prison. A month later the governor met their request. [vi]

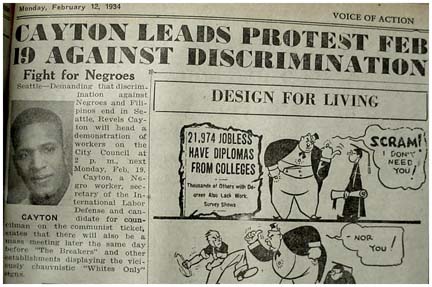

The Party also engaged in activities to improve the conditions of people of color in the Seattle area. Cayton started the Seattle Chapter of the League for Struggle for Negro Rights (LSNR) in 1934. This was a Party sub-group directed at organizing a mass movement among African Americans to demand equal rights. While the local chapter was successful in recruiting more African Americans into the Seattle Communist Party,

Revels Cayton, grandson of Mississippi reconstruction Senator Hiram Revels and son of Horace and Suzie Revels Cayton, joined the CP in the early 1930s and led its organizing efforts in Seattle's African-American community. This city council demonstration attracted considerable attention. Voice of Action February 12, 1934.it had limited success meeting its other goals and was disbanded in 1936. Nevertheless, before it dissolved, the LSNR was responsible for organizing various protests against segregation and discrimination and generally increasing the public’s awareness about the issues. [vii] In 1934 Revels Cayton campaigned for Seattle City Council on the CP ticket.. His entire platform, which gained some community support, was based on the issues of racism and discrimination in Seattle. The Party stood firmly behind Cayton by organizing several small marches around the city collecting “Whites Only” signs and removing them from local businesses. While Cayton was not successful at winning the City Council seat, the Party did raise the racial consciousness of the general public. [viii]

The Party persisted in its resolve to publicize conditions. For example, in the 1940s members acted to uncover

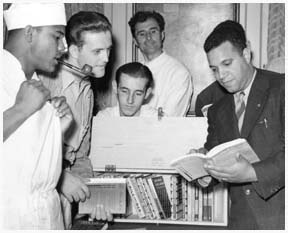

Revels Cayton (on right), in 1934 became a leader of the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union, which later became affiliated with the ILWU. In the 1940s Cayton becomes head of the west coast CIO. (courtesy ILWU Dispatcher)businesses that were discriminating in hiring practices. Lonnie Nelson, a current member of the CP, recalls testing businesses by being paired with an African-American to jointly apply for work. The Party also continued the legal battle for equal rights. John Daschbach, a lawyer and an active member of the Communist Party, founded the Washington Civil Rights Congress in 1946 to stand in the “defense of constitutional rights and civil liberties of the American people, including Communists and Negroes.” The organization was active in the courts until 1956 when it dissolved after being investigated by the Subversive Activities Control Board as a Communist-front group. [ix]

While the Party was involved in community, legal, and political actions around the issue of race, the vast majority of its work occurred in the labor sector. Because unions had exclusionary practices and were frequent initiators of racist actions, most people of color did not feel any loyal to unions and justifiably resisted attempts to enforce closed shops in traditional industries. A closed shop would establish a union as the only hiring system and would often exclude non-whites. This combination of class exploitation and racism made for a volatile situation as people of color from outside the community were brought in to break strike lines. The Party, seeing how a racially divided workforce was weakening the workers’ movement, became involved in desegregating unions. [x]

The Communists’ greatest success was influencing integration of the International Longshoremen’s Association, one of the more progressive unions. This union had been instrumental in organizing the general strike of 1919; and, after the strike, because of extreme pressure from Communists and members of the IWW, actively began recruiting people of color. Frank Jenkins, an African-American Communist, became a leader in the Longshoremen’s Union, joining when membership was opened African Americans. He helped design what he called a “truly democratic union” that allowed the general membership to make the decisions. Jenkins, with the help of other Communists and labor leaders, pushed include anti-discrimination language in the Longshoremen’s constitution. As a result of his efforts the Longshoremen adopted a policy that banned discrimination based on a person’s race or political affiliations. [xi]

Earl George

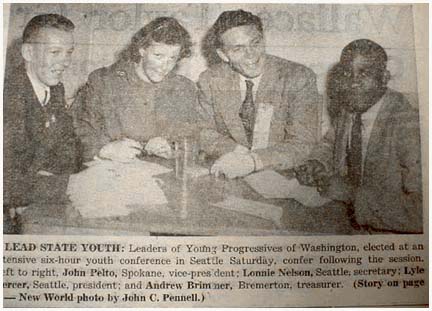

Lonnie Nelson and other Young Progressives of Washington campaigning for Henry Wallace in the 1948 campaign. New World April 22, 1948. See her discussion of "testing" and other anti-discrimination activities in her video interview.The ILWU leadership was becoming increasingly radical and Communist. Under leaders like Earl George and Frank Jenkins, the communist factions within the ILWU continued to work on issues of equality within the union. Despite the non-discrimination language in the constitution, seniority for people of color was often denied and preferential job placements for white workers continued. The Communist faction within the ILWU addressed these inequities within the union system, although success was marginal. Nevertheless, some of the greatest changes made in the ILWU, on a local level, occurred when the majority of the Local’s leadership was Communist.

During the Red Scare of the late 1940s and early 1950s, the ILWU was investigated for un-American activities and for harboring Communists. The president, Harry Bridges, arrested multiple times for suspected Communist membership, was later found not guilty after several investigations. The ILWU was eventually disaffiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations based on the CIO’s opinion that ILWU was full of Communists. According to Frank Jenkins, the CIO action was less due to Communist-Party status than to the ILWU’s history as a radical, democratically-run union.

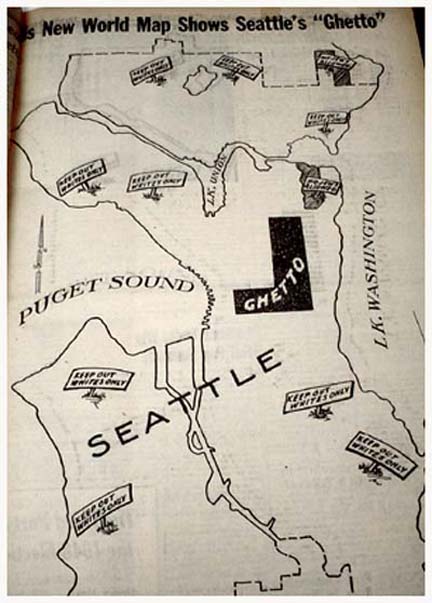

In a January 15, 1948 article, the New World attacked the widespread use of restrictive covenants in Seattle neighborhoods and mapped the city's Central District "ghetto."During the ILWU’s struggle with radicalization and integration the Longshoreman became increasing aware of the conditions that workers endured in the canneries of Alaska. Cannery plants at the time essentially worked on a slave-labor system. Young, primarily Filipino, men were taken to Alaska, usually to pay off their passage from the Philippines or other inflated debts. They endured terrible conditions to work off a ‘debt’ that was greater then the amount they would ever be able to pay. In an attempt to improve the working conditions of all maritime employees, a massive organizing campaign took place, and in 1933 the Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers Union (CWFLU) was formed. This was the first Filipino-dominated union, and one whose membership was primarily people of color. The union later affiliated with the ILWU becoming ILWU, Local 7 in 1950.

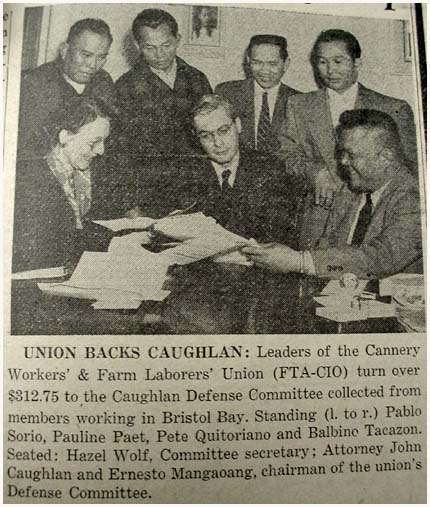

The majority of the CWFLU leadership was Communist. They struggled with the working conditions in the plants and with persecution based on race and political affiliation. CWFLU was successful in changing the working conditions of the plant workers while also building a solidarity movement along the Pacific Coast. In 1949 all the officers of CWFLU were arrested for being Communist, and, being foreign born, were set to be deported. The CP successfully protected these leaders from deportation. In 1950 the arrested leaders of then ILWU, Local 7, were released because the Philippines was a United States territory and, therefore, citizens of the Philippines were United States nationals. The release was based on the landmark United States Supreme Court Decision, Mangaoang v. United States, which was won by Party lawyers paid with Communist-Party funds. [xiii]

The Communists of Washington State were also instrumental in the integration of the local chapter of the Steelworkers of America. Like the Longshoremen, the Steelworkers had encountered problems when trying to build a solidarity that was limited to white workers only.. Pushed by Communist members to be more inclusive, the Steelworkers acted to open membership to all workers. Eugene Dennett, one of the known Communists in the Steelworkers union, encouraged African-American workers to join the Party, and, at the same time, focused on eliminating discriminatory practices of his union. [xiv]

The foregoing is an incomplete list of Communist Party efforts to integrate unions. The Party was also very involved in racial struggles within the Communication Workers of America, the International Woodworkers of America, and the Musicians Union. In fact, Party members, both individually and collectively, were actively involved in the racism issue in most of the Pacific Northwest unions.

But, while the Party struggled on issues of racism and discrimination and contributed positively to the civil rights struggle, it appears that its involvement was at times more about strengthening the workers’ movement than from a genuine interest in improving the lives of people of color. Even after the Party began working on integration within the unions and the community, it continued to advocate separate organizations within the Party for people of color, rationalizing that these would provide an outlet for empowerment through self-

When attorney John Caughlan was arrested for perjury after denying membership in the Communist Party, the Cannery Workers joined other left groups in raising money. A year later Mangaoang and other union leaders were threatened with deportation. (New World August 9, 1948). determination; However, these sub-groups were not well supported and eventually faded away, as was the case with the League for Struggle for Negro Rights. The Party, concerning itself with the ending of capitalism, used issues of discrimination as a catalyst for inciting larger support for its original goal, opportunistically using racism to highlight the wrongs of the economic system. The Party never adopted a different framework for analysis of racism that addressed issues outside of economics, as, for instance, when the Party did not contest the internment camps for Japanese Americans during World War II. This discrepancy between adopted tenet and practice led to the disillusionment of those several Party members who were working on issues of racism. Revels Cayton, one of the best-known advocates against racism, left the Party after realizing it was only interested in talking about race when that issue applied to Party strategy.

Although the Communist Party of the Northwest in the decades of the 1930s through the 1950s did significantly contribute to the improvement of the lives of people of color, its legacy should not be uncritically assessed. While the Party was one of the first primarily-white organizations to become involved in the issue, it did so from the standpoint of bettering the struggle for workers. Its narrow focus on issues that related directly to Marxian theory and Party platform caused it to ignore issues it should have addressed, while claiming to support principles on which it actually had not taken a stand.

Next: War and Red Scare: 1940-1960

[i] Lenin, Collected Works, Vol XIX, p 92

[ii] Gus Hall, Fighting Racism: Selected Writings (New York: International Publishers, 1985), 37.

[iii] Robert Pitts, Organized Labor and the Negro in Seattle (University of Washington, 1941)

[iv] Gus Hall, Fighting Racism: Selected Writings (New York: International Publishers, 1985)

[v] Richard Hobbs, The Cayton Family Legacy: Two Generations of a Black Family, 1859-1976 (University of Washington, 1989)

[viii] Ibid, (223-300)

[ix] John S. Daschenbach personal papers, University of Washington

[x] Robert Pitts, Organized Labor and the Negro in Seattle

[xi] Frank Jenkins, interview in personal papers, University of Washington

[xii] A Tribute to Earl George: 90 Years of Struggle (2001) available on www.cpusa.org/article/articleprint/239/

[xiii] Introduction to the Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers’ Union, Local 7- CWFLU papers University of Washington

[xiv] Eugene V. Dennett, Agitprpop: The Life of an American Working-Class Radical (New York: State University of New York Press, 1990)