Described as one of “the greatest moments of working-class solidarity and militancy in American history,” Seattle’s 1919 General Strike demonstrates both the strengths and limitations of collective action in the labor movement during the twentieth century. [1] The role that gender and race played in the strike reveal how this moment is both a story of worker solidarity and of exclusion. Although historians have studied the ways in which labor movements excluded White women and workers of color, they have shed less light on how racism and sexism intersected to exclude women of color from White women’s movements. Largely kept out of male-dominated spheres but racially privileged themselves, White women’s racist rhetoric and practices leading up to the General Strike played a crucial role in excluding Black and Asian American women from Seattle’s labor movement and thereby from the mainstream narrative of the General Strike itself.

Although labor movements in the U.S. are made up of a range of anti-capitalist, or at least pro-worker, progressives and leftists, the speeches and actions of many labor organizations and unions have reflected and reinforced white supremacy in its most brutal forms. Washington State is no exception. White workers in Bellingham, for instance, violently attacked and drove out East Indian immigrant workers who they perceived to threaten them economically.[2] The American Federation of Labor (AFL), nationally and locally, excluded workers of color as well. According to historian Dana Frank, out of more than 100 locals affiliated with Seattle’s Central Labor Council in the early 1900s, “only 9 ever admitted workers of Asian or African descent on any terms.”[3] Members kept these workers out through practices such as informal blackmail of prospective members and explicit racial and citizenship codes in their union constitutions.[4]

Despite Whites’ attempts to erase workers of color, Black and Asian workers constituted an important part of Seattle’s labor history and resisted white supremacy in Seattle’s labor movement. In the early 1900s, Black Americans constituted just 1 percent of Seattle’s population; 2.5 percent of the population were Japanese American.[5] Japanese men worked in stores, domestic service, and in canneries, sawmills, and laundries. Women primarily worked in service occupations. Fewer than 1,000 Chinese Americans resided in Seattle in a Chinatown painstakingly rebuilt after the driving out campaigns that White workers executed in the 1880s. In the face of exclusion, workers of color created and strengthened labor organizations within their own communities. Japanese immigrant workers started their own completely separate trade unions and business associations by 1906. The Nihonjin Rodo Kumiai (Japanese Labor Association) and unions for butchers, shoemakers, and barbers had hundreds of members.[6] Many Japanese immigrant workers, along with an estimated 300 Black men, joined in the General Strike.[7]

Although White women’s race protected them from the marginalization that communities of color faced, White women occupied a subordinated, denigrated position within the American Federation of Labor. Seattle was notable in the early 20th century for the strength of its labor movement and for the number of unions that included or consisted entirely of women as historian Karen Adair details in her book Organized Women Workers in Seattle 1900-1918. Yet many Seattle unions only welcomed women’s organizations as an auxiliary. Moreover, even those like the Retail Clerks Union that welcomed women on an equal basis with men required them to pay the same initiation fees and dues despite the fact that women who worked in stores made approximately one-half the pay of what White men received.[8] Eventually, due to pressure from other unions, the Seattle male clerks dropped union fees to $1.00—an improvement, but still a large portion of the women’s weekly earnings.[9] Although union men eagerly recruited more women, they did not address women’s concerns. The men regarded them as “adjuncts to organized labor” not a vital part of the union. [10]

Women-led unions

Reformers in Washington State attempted to deal with these concerns by passing “The Piper Minimum Wage Bill,” in 1913. Although this bill did benefit women workers, its motivations were largely sexist. Those who supported it, including many women reformers, hoped this legislation “uplift the morals and protect the health” of women workers. [13] Senator George U. Piper claimed that women would turn to “earnings of shame” if they continued to receive insufficient wages.[14] Despite the material benefits they helped to provide, protective legislation like this simultaneously reflected and reinforced misogynistic paternalism and gendered stigma attached to certain types of work and to sex work. It should be noted, additionally, that reformers exclusively expressed concerns about women workers’ health and morals in the case of White women—not women of color.

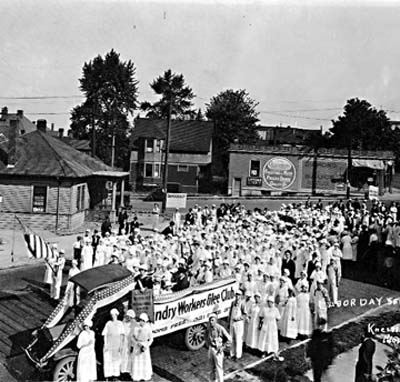

The women in Local 240 did not challenge the logic used by their critics but relied on respectability politics to defend themselves. Like other waitresses unions, Local 240 excluded women with “immoral reputations,” emphasized that they performed a “skilled craft” rather than “unskilled labor,” and refused to perform “demeaning chores such as scrubbing floors, washing dishes, and performing other maintenance work."[15] These women likely responded in this way which, in the long-term, reinforced highly gendered and racialized stigmas due to social pressures and the onslaught of criticisms against their ranks and leaders which aimed to undermine their cause altogether. When the women tried to appear ladylike by organizing social functions where delegations of waitresses appeared dress in all white,[16] a writer for the Union Record concluded that “if these girls are fair representatives of the beauty of the entire membership, it will require no matrimonial bureau to rapidly decimate the ranks” of their union.[17] Misogynistic and condescending language about the women unionists reflected and reinforced gendered disparities and motivated these women to attempt to gain short-term respect at the cost of long-term transformation of social attitudes.

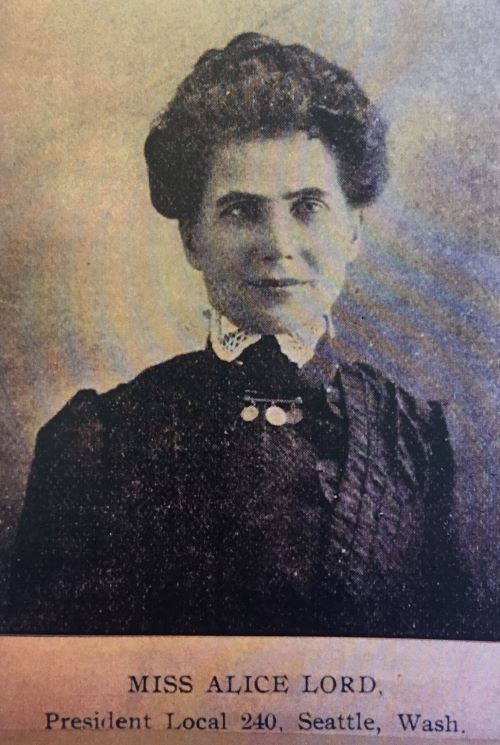

Alice Lord, president of Local 240, urged members to defend themselves through expressions of respectability and social conformity. She avoided creating confrontations with male unionists over their treatment of women workers, instead winning their cooperation through her wit. For instance, instead of shunning labor council meetings due to cigar smoke which some believed would be offensive to the women, she and the waitresses claimed they didn’t object to the smoke and indeed enjoyed “the aroma of a union-made cigar.”[18] She also assured others that she “did not believe in women working at all” and instead argued that, “if compelled to [work], they deserved as good conditions as men.”[19] Nonetheless, she was one of many women who departed from standard feminine roles to lead the labor movement. She found success in male-dominated labor circles precisely due to her “unfeminine traits.”[20]

Not everyone appreciated women labor leaders. A local editor referred to Lord as a “neuter blossom”[21] due to her suggestion that women’s worth resided in spheres external to their homes. He also accused the waitresses of being “foolish” for electing a woman as their president.[22] He went on to argue that:

A young woman who will have the unblushing, immodest temerity to stand up, being the only woman amidst 250 men, and “pronounce the benediction,” as was done by a Seattle woman in Tacoma last week, has lost all sense or appreciation of modesty or propriety … Every modest women must blush for the temerity of this amazon, and every virtuous man should curse this exhibition …. The very fact of such meetings being conducted quietly and orderly, under the influence of the ‘political petticoat,’ shows the greater degeneracy, for it is sure evidence that ‘feminine cunning’ has been permitted to restrain, if not usurp the functions of masculine virtue.[23]

Despite misogyny, leaders such as Lord led to a generation of waitresses who assumed leadership in their movement.[24] Through their trade unionism, Lord and her waitresses achieved greater economic and social security for themselves. In 1906, their wages had risen an average of fifteen percent and their day had shortened an average of three hours since they began organizing. They additionally received sick, accident, and death benefits that they previously lacked.[25] These union gains, however, would be for White women only, because Local 240 excluded nonwhite women from their membership.[26]

Practicing white supremacy

White women were not mere victims of sexism, but active participants in the labor movement’s white supremacy. Most union internationals let individual locals decide whether to include Black workers. Still, prior to World War I, nearly all Seattle unions excluded Black and Asian American workers.[27] After the war, Seattle waiters admitted Black men as members because they feared losing more of their jobs to lower paid waitresses. White waitresses, meanwhile, maintained their all-white membership.[28] Waitresses excluded Black women but particularly targeted Asian American women. This was partly because they did not see Black workers as a threat, likely due to their small population in the city.[29]

Beyond excluding non-white workers, unionized women boycotted non-white-owned businesses and white-owned businesses that hired non-whites. In the 1890s, cooks and waiters initiated a campaign to eliminate Seattle’s Japanese restaurant trade. When the waitresses organized in 1900, they supported these exclusionary policies.[30] Racist boycotts targeted Asian workers, whom Whites saw as competition for jobs and threats to their locals. It seems that women did not see the hypocrisy in excluding these workers, whose employers clearly treated them poorly and who needed unions. White business owners paid non-unionized Asian American workers approximately one-half to two-thirds of what they paid White workers, all while requiring them to work for 10-12 hours per day, seven days per week.[31]

To target these non-white workers, Alice Lord condemned “Japanese business aggression”[32] before the state legislature in 1921 and protested the proposed admission to unions of Asian American workers who were U.S. citizens.[33] She also helped defeat an amendment at the 1923 General Convention of Hotel and Restaurant Employees International Union that would have eliminated the constitutional restriction barring Asian Americans from membership in any local affiliate, a measure proposed by the culinary workers union in San Francisco.[34] Indicating her motivation, she wrote that her union was “getting along very nicely” despite having “great odds to fight against, namely the Japanese cafes and dairy lunches[.]”[35] At one point, she also proclaimed that no “American” waitress would ever work for a Japanese or Chinese employer, or in an establishment which hired Asians. [36] Not surprisingly, Lord went on to lead the Japanese-Korean Exclusion League that labor activists had founded in 1908, and frequently published attacks on Seattle’s Asian residents.[37]

Pauline Newman, a leader in the culinary crafts joint board, was another White woman who supported boycotting these businesses. She stated that there were “a number of good, fair eating places” that supported unions and employed “Americans.” She warned Seattleites to “bear this in mind when looking for a place to eat.”[38] Similarly, a woman named Jean Stovel, spoke on behalf of the Women’s Card and Label League to recount the origins of the union label: “In 1873 in San Francisco several cigar manufacturers tried to import coolie labor and it was agreed by the workers that boxes must be labeled white to indicate that white hands had made the cigars.”[39] Clearly, to White women unionists in Seattle, terms such as “American” and “workers” meant “white.”

Although sources that center women are limited, it is clear that White women unionists who perhaps could have worked alongside non-white women instead chose racism over solidarity. Although some workers of color participated in the strike, “racial exclusion was at the center of that strike for many of its participants, and it was central to the vision of workers’ empowerment that underlay their activism.”[40] This was true not just among White men, but among White women who used racist respectability politics to defend themselves and who deliberately undermined and targeted workers of color. As a result of this racism and sexism, we continue to have little information on women of color’s thoughts on, feelings about, and experiences and participation in the strike.

The gap in our historical narratives of the General Strike narrative is no accident, but results from racism and sexism which often obscures the lives of marginalized groups. The erasure of women of color in the mainstream history of the strike itself, however, gives some indication about raced and gendered dynamics of Seattle’s twentieth century labor movement. Although the General Strike tells a crucial story of solidarity among Seattle’s workers, it also demonstrates clear limits to the Seattle labor movement and the progressivism of the involved activists. White labor activists, including women, prioritized racism and sexism to the detriment of their own class interests and in ways that directly harmed non-white workers, and especially women of color. As Seattleites and others in solidarity celebrate the anniversary of the General Strike, we should not romanticize this piece of labor history but instead draw attention to and learn lessons from the ways that labor movements have neglected and harmed the most vulnerable communities of workers.

(c) 2019 Kathryn Karcher

HSTAA 353 Spring 2019

[1] Dana Frank, “Race Relations and the Seattle Labor Movement, 1915-1929,” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 86, no. 1 (1994/1995): 35.

[2] Professor Moon-Ho Jung, “Contesting and Reinforcing Race and Empire” (presentation, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, January 17, 2019).

[3] Frank, “Race Relations and the Seattle Labor Movement,” 35.

[4] Frank, “Race Relations,” 35.

[5] Carole Davison, “Seattle’s ‘Restaurant Maids’: An Historic Context Document for Waitresses’ Union, Local 240, 1900-1940” (unpublished MA thesis, University of Washington, 1998), 80.

[6] Frank, “Race Relations,” 36-37.

[7] Frank, “Race Relations,” 38.

>[8] Karen Adair, Organized Women Workers in Seattle, 1900-1918 (Seattle: University of Washington, 1990), 156-160.

[9] Adair, Organized Women Workers in Seattle, 162.

[10] Union Record, July 24, 1900.

[11] Davison, Seattle’s “Restaurant Maids,” 66-74.

[12] Adair, 183.

[13] Joseph Tripp, “Toward an Efficient and Moral Society: Washington State Minimum-Wage Law, 1913-1925,” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 67, no. 3 (1976), 97.

[14] Tripp, “Toward an Efficient and Moral Society,” 100.

[15] Adair, 184.

[16] Adair, 185.

[17] Union Record, September 8, 1900

[18] Adair, 191-192.

[19] Union Record, October 17, 1908.

[20] Adair, 191.

[21] The Patriarch, May 4, 1907, quoted in Karen Adair, Organized Women Workers in Seattle, 1900-1918 (Seattle: University of Washington, 1990), 194.

[22] The Patriarch, January 25, 1905, quoted in Adair, Organizing Women Workers in Seattle, 194.

[23] The Patriarch, September 5, 1908, quoted in Adair, 194.

[24] Adair, 193.

[25] Adair, 195-196.

[26] Davison,78-81.

[27] Frank, “Race Relations,” 36-38.

[28] Davison,82.

[29] Dana Frank, Purchasing Power: Consumer Organizing, Gender, and the Seattle Labor Movement, 1919-1929 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 228-229.

[30] Adair, 208.

[31] Davison, 80.

[32] Union Record, February 8, 1921.

[33] Frank, “Race Relations,” 38-39.

[34] Davison, 83.

[35] Mixer and Server, September 1910.

[36] Adair, 209.

[37] Adair, 209.

[38] Union Record, June 18, 1925, quoted in Dana Frank, “Race Relations and the Seattle Labor Movement, 1915-1929,” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 86, no. 1 (1994/1995): 42.

[39] Union Record, January 18, 1921

[40] Frank, “Race Relations,” 38.