By Sarita Y. Shukla and Rebecca M. Price

Originally published in 2018 on the UWB Digital Learning and Innovation Blog

Engaging with course materials is the quintessential ingredient for student success. We want our students to engage deeply with our reading assignments by taking notes, asking questions, and discussing the text with their peers. Web annotation tools are a new way to promote this kind of student engagement. They offer a way for students to chisel out their intellectual interests while learning deeply and growing mentally.

We’ve had the opportunity to play with two platforms for web annotations, Hypothes.is and Perusall. Here are the instructions/videos for instructors and students on how to install and use these platforms:

- Introduction to Hypothes.is for instructors

- Introduction to Hypothes.is for students

- Introduction to Perusall for instructors

- Introduction to Perusall for students

The table below briefly compares Hypothes.is and Perusall. After the table, we discuss our experiences with each platform.

We thank our colleagues, Jane Van Galen, Todd Conaway, and Eva Ma for encouraging and supporting our exploration of these platforms.

Comparison of Hypothes.is vs. Perusall

| Hypothes.is | Perusall | |

| Cost | Free to students and instructors | |

| # of articles | No limit on the number of articles that you can annotate | |

| Open source software? | YES | NO |

| Article type for annotating | Open access articles available via the web | Only PDFs uploaded by the instructor |

| Can this integrate with my LMS? | No, not currently | Yes, but UW doesn’t allow it (yet) |

| Students can ask and answer questions | YES | YES |

| Students can share and reply to reflections | YES | YES |

| Ease of grading | See Sarita’s reflections | Depends, see Becca’s reflections |

by Sarita Shukla

In the myriad of tasks that often consume college students’ limited time, completing required course readings tends not surface at the top of the list because it doesn’t seem worthwhile. In my own experience, some students often come to class having skimmed or not having read the required course materials. This may prevent them from contributing to class discussions meaningfully. They are also likely to become passive recipients of information from others while fellow students miss out on getting varied perspectives which would lead to a richer and more dynamic understanding of the course content. The challenge is to make readings worthwhile to students.

I had a eureka moment to this vexing pedagogical problem, when my colleague Dr. Jane Van Galen introduced me to hypothes.is, a web annotation tool. I started thinking about web annotations as a source of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation for students to complete the readings. Extrinsic motivation may come in the form of points attached to posting annotations for required course reading. On the other hand, intrinsic motivation may come in the form of opportunities to engage with peers (albeit asynchronously), which meets students’ social needs to belong and connect. Additionally, intrinsic motivation may also be enhanced by meeting students cognitive need (see Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs) to complexify texts and “see” different perspectives while having the time and space to process this information.

So, I decided to use hypothes.is as my course web annotation platform (for a discussion on hypothes.is see this blog post by Remi Kalir). The assignment prompt outlined the steps for starting and activating hypothes.is. I required students to post at least 3 annotations per reading in our private hypothes.is group (step-by-step instructions for starting your own private group). The annotations could take the form of expanding or relating some part of the reading to prior experiences, posing questions, or replying/adding onto fellow students’ annotations. My courses are small, so I combined students from two sections into the group, for a total of 33 students. Students had one to two weeks to annotate the readings, and the annotations were due before the class session when we discussed the readings. We then discussed students’ questions and comments in our face-to-face meetings.

The Hypothes.is tools are visible on the right.

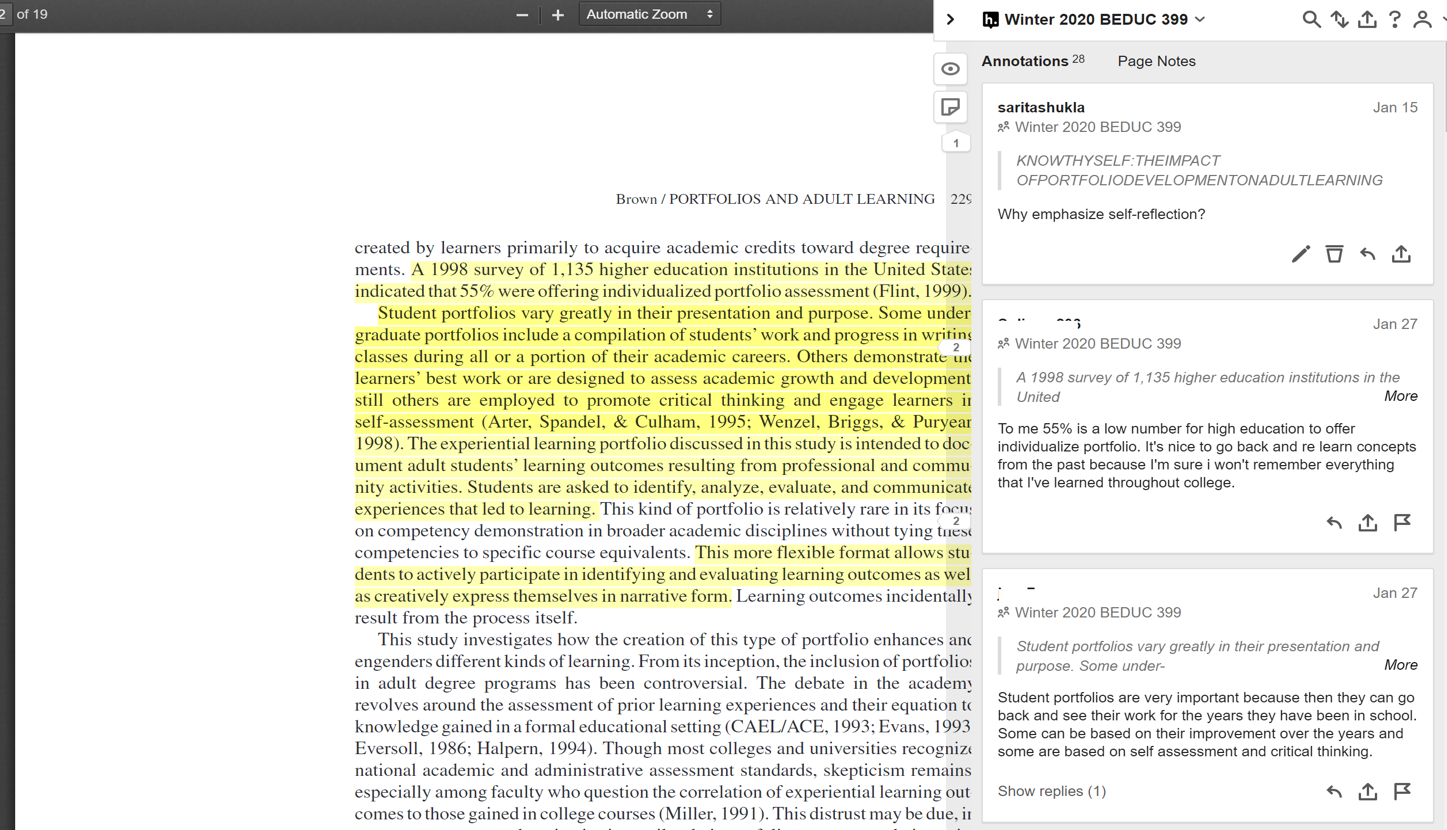

There were quite a few things that I learned from using hypothes.is as a web annotation tool for my classes. The best part was that my students absolutely loved this tool. Almost all students considered this tool to be better than the use of Canvas discussion boards. Students noted that they really enjoyed seeing annotations in context and particularly enjoyed replying to fellow students’ comments in context.

This image shows the same page from above, but with student annotations.

There were several challenges that I grappled with as well. For instance, I found that several students adhered to the three-annotation requirement and once they met this criterion they stopped. I also noticed that there were very many annotations at the beginning of a text and then annotations trailed off towards the end of the text. In the future maybe, I will try “comment throughout the document.” I am still trying to decide about the required number of annotations e.g., 5-7 annotations.

Making a private group was helpful. It meant that only the students in my class could comment, which made it relatively easier to follow students’ thought processes, understand the varied connections to prior experiences, and interpret the questions posed by this group of students; however, I realized that having 33 students in one hypothes.is group is not optimal. This is because I had so many comments in one group, once students highlighted one part of the reading, the whole text ends up looking yellow (highlighted). In the future, I am considering having 7-8 students per group.

Hypothes.is does not have a built-in grading system. However, the dashboard for the private group shows the number of annotations made by each of the members of the group. Unfortunately, hypothes.is only counts the number of original annotations, excluding the number of replies to fellow students’. I did my grading in Canvas — that’s where I commented on students’ annotations. This required that I keep a codebook that linked real names to aliases in hypothes.is, e.g., connecting the alias Happy24 to the student Priya Jones.

Since hypothes.is is open access, the articles that I linked to my private group had to be openly available too. This was a challenge because a few of the assigned articles were behind paywalls. I am still trying to figure out if there is a way to assign readings that might not be freely available on the web but could be made available to my students for annotations using hypothes.is.

Overall, I have enjoyed the level of engagement that my students demonstrated using this free, open access platform. Once I work through the challenges posed above, I will meet students’ needs even more–and reduce the amount of time I spend grading.

by Becca Price

I teach hybrid courses that blend face-to-face time with more online instruction than what occurs traditionally. Since I want my classes to be student-centered, I want students’ ideas about the text to guide instruction in our face-to-face meetings.

I’ve found Perusall a great way to build community and focus instruction on what students find intriguing about the readings.

The approach I’ve been using in our local LMS doesn’t seem to foster that kind of community and reflection. I’ve used small group discussion boards, breaking students into groups of about 5. I pose a series of about five questions, and ask each student to answer. After this initial post, they can see what their peers have posted. Within two days of the due date for that assignment, they need to reply at least two times to other group members. Although we work on how to write substantive replies, I often get posts like “Gee! That was really interesting. I hadn’t thought of that before.” Even the initial posts lack depth—for example by posing a question that’s generated early in a reading, but answered later on. The students aren’t indicating that they’ve engaged with the whole text.

I wanted to see if it would work better to use a platform that allows students to annotate text in collaboration with each other. Because one of my courses requires reading extensively from the primary literature, I decided to use the free app Perusall, through which students can collectively annotate any PDF. Another platform, hypothes.is, allows students to share annotations on websites.

Perusall has a number of built-in features that are quite convenient. It’s easy to assign readings, and indeed to break them apart over several due dates. There’s an automatic grading feature, which seems to work based on how a student’s comments are distributed through a document, the number of comments, and the number of questions. The grading feature seems to work best on a coarse scale (e.g., 3 points) rather than a fine one (e.g., 10 points). However, I usually end up exporting students’ comments into a spreadsheet, and sorting the comments by students’ names.

As you can imagine, it can get quite messy when many students are highlighting text to write their annotations. So, small groups are helpful, to avoid having the text get too messy and having too many comments to read and sort through. Smaller groups can lead to true conversations that are taking place about a text, because students can write more in-depth analytical comments. I take advantage of Perusall’s ability to assign students randomly into groups. I started with groups of five, but I think these groups were too small. Next time, I’ll divide students into groups of eight, which I think will mean there are at least three students in each group who want to participate in an in-depth discussion, and who can set the bar for other students about where conversation can be.

The messiness of multiple annotations makes it hard to sort through students’ comments. It’s also rather cumbersome to focus on one student’s or one group’s comments; both of these options require lots of clicking and scrolling in Perusall, and since I’m usually working from my small laptop screen, that is a challenge. To get sense of students’ comments, then, I download a spreadsheet with all comments. I could sort these by the order they appear in the text, and then move between the spreadsheet and the text to track the comments. In fact, what I usually do is sort by student, so I can get a sense of the way each student works through the text. Then, as needed, I go back to a group’s page to interpret comments in the context of a whole discussion. But it’s not easy to find out to which group a student belongs. This is how I assign grades, or check them against the automatically assigned grades.

I found that students were more motivated to complete the readings in Perusall, and that they were motivated to check back on the site to see how comments changed. If a student poses a question, for example, they want to log back on to see if it has been answered. The discussion board in the LMS, however, felt to the students more like busy work—they had to check back in on the discussion because it was a course requirement, not because of any intrinsic curiosity.

They are choosing which parts of the text they find most engaging or most confusing or most inspiring for future research, so my teaching responds to their interests. My homework prompts work well even—or perhaps especially—when they are vague. Instead of giving them questions to answer, I can say “read and annotate”—and they do.

The vagueness of a prompt like “read and annotate” helps me meet another learning goal: the ability for students to think about whether they have gained what they can about the reading. Thus, I don’t ask them for a particular number of annotations. Instead, I ask them to make annotations to indicate that they’ve engaged with the whole reading. I blame the grading on Perusall, reminding students that the app looks at the number of comments, their length, and the way they’re distributed through the text. This contributes enormously to the student-centered nature of the annotations and subsequent in-class discussions.

Now my students are engaging deeply with texts and their conversations tell me what to emphasize in our subsequent face-to-face meetings. This student-centered approach is what I’ve enjoyed most about Perusall.