Home Find an Organization Methods & Links Map Gallery Concepts & Research Update Stew-MAP

Stewardship Concepts & Research

More studies are under way to learn about how civic environmental stewardship can improve natural resource planning and management. Additional concepts and research include:

Understanding the Stewardship Footprint

Natural systems across the entire urban-wildland landscape gradient face ongoing threats. Yet fiscal shortfalls in local government and environmental resource organizations limit their capacity to address ecosystem needs and recovery. In the face of limited and declining fiscal and technical resources for ecosystem management, society must consider new solutions to restore and sustain natural systems across the landscape gradient. Engagement of human systems, from individuals to organizations, is essential. Some ecological research describes human, or anthropogenic, effects as inherently negative, suggesting that the public is largely uncaring or even intentionally destructive. A contrasting perspective is that people can interact with landscapes for mutual benefit. The ecological footprint concept summarizes urbanization demands and negative ecosystem impacts (as described by Wackernagel and Rees 1996). However, the footprint metaphor can also be applied to the positive consequences of human action on the landscape, and to better understand interactions between ecological and social benefits of stewardship activities. The Green Cities Research Alliance (GCRA), being a group of organizations and scientists, is working on a research program to evaluate how well bottom-up environmental stewardship (ES) activities contribute to achievement of top-down institutional policy and program objectives for resource conservation (such as estuary recovery and urban forest restoration).

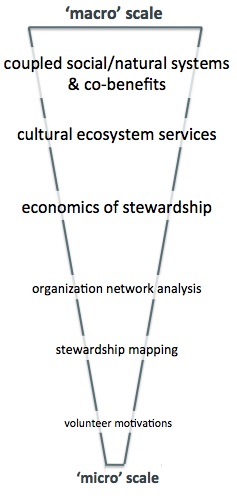

The GCRA is treating stewardship not as isolated, occasional actions on the land, but as a set of comprehensive and complex ecosystem-based actions and projects. We seek to better understand the pathways and processes by which the ecological and social footprints of stewardship interrelate at the individual, group, and community levels. Studies include:

- surveys of individuals who participate in stewardship events,

- the organizations that host and sponsor the ES work, including mapping of their work sites and areas,

- the economics of stewardship, such as benefit/cost analysis,

- the benefits that individuals and communities gain from healthier ecosystems, termed ecosystem services, and

- an understanding of how stewardship programs connect to the natural systems goals of agencies, and resulting co-benefits.

Over time, then, the research products will be a comprehensive understanding of how and why ES is conducted, methods for identifying gaps in ES activities, and how ES efforts could be better mobilized to address concerns of urban ecosystem health and sustainability.

For more information: Wolf, K.L., D. Blahna, W. Brinkley, M. Romolini. 2013. Environmental Stewardship Footprint Research: Linking Human Agency and Ecosystem Health in the Puget Sound Region. Urban Ecosystems 16: 13-32.

Social Network Analysis

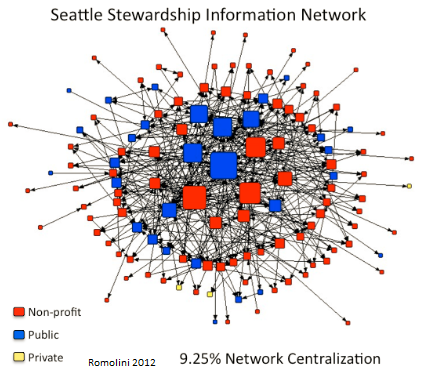

One organization can help build stronger communities and improve the environment, but it is only one part of a larger picture. Given the relationships and overlap among those working on the environment, it is important to understand the networks that tie them together. Social network analysis can be a powerful tool to show how different types of organizations cooperate and collaborate. The figure on the left shows the relationships between 144 stewardship organizations in response to the survey questions:

- From whom have you received information, advice, or expertise related to environmental stewardship in the past year?

- To whom have you provided information, advice, or expertise related to environmental stewardship in the past year?

Thus, this figure depicts the information network of non-profit (red), public (blue), and private (yellow) sector stewardship organizations in Seattle. The arrowheads show the direction of the relationships, which can be either one-way or two-way ties. The size of each organizational node is relative to the number of ties it holds with other organizations. Those with a greater number of ties are considered to be more active in the network. While the public sector makes up only 21% of the network compared to 75% representation by non-profits, public agencies are among the most active, with several holding the largest number of ties.

These types of analyses and illustrations may help provide practitioners with a more accurate understanding of the network and their organization's role in it. Network participants may also wish to actively manage the relationships within the network and reach out to those that are disconnected. It may also help organizations within or outside the network seeking to target the most connected organizations in an effort to get a message out to the entire network.

Relating Forest Conditions to Stewardship Activity and Environmental Equity

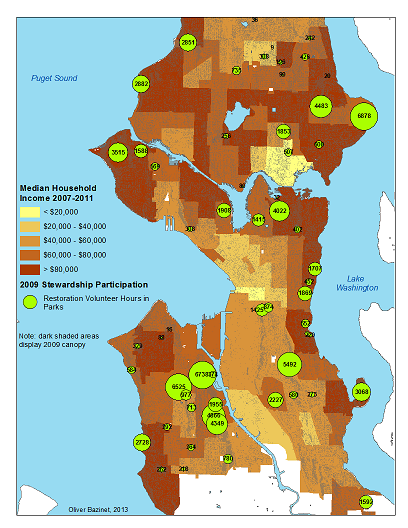

Community stewardship of natural resources can have outcomes that are both ecological and social in nature. Because citizen stewards often choose volunteer locations based on emotive connections or proximity to their homes, restoration activities may not be distributed equitably across the socioeconomic populations of a city. An inter-agency team is looking at the relationship between community stewardship within the City of Seattle's Green Seattle Partnership program - particularly its spatial concentrations in relationship to canopy cover and social-economic variation throughout the city.

Seattle will serve as a pilot project, however the approaches developed here are aimed at urban areas in general and will provide a framework for similar analysis for regional, national and international comparisons. The three research questions are:

- How is the overall urban forest canopy characterized across Seattle and what type of variability is observed in forest patch structure and health condition within and between neighborhoods?

- What is the structure and health condition of forested patches in which stewardship projects have taken place versus those that have had little to no recent stewardship activity?

- How do neighborhood demographic characteristics compare with the distribution of total forest canopy, 'healthy' forest patches, and stewardship activity?

These findings will develop innovative, more accurate and cost-effective approaches for urban forest assessment. While past studies have investigated the relationships of urban forest and parks distribution in relationship to socio-economic conditions, this study will further build understanding about the spatial relationships of healthy forests and human populations.

Copyright 2013 University of Washington School of Environmental and Forest Sciences • Created with the support of: