Seattle had known many strikes, but the one that started on August 13, 1936 was different. Striking for the first time were white-collar professional employees - journalists - whose recently founded union, the American Newspaper Guild, had taken the bold step of declaring the walkout. And it was indeed a bold step because they were taking on the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, part of the Hearst empire of newspapers, magazines, wire service, newsreel and film studios. The fifteen week strike would make history, ending in a victory that helped secure the future for the Newspaper Guild while proving that William Randolph Hearst, the ruthless and reactionary boss of the nation's largest media chain, could be defeated if not tamed.

It began quietly on the morning of August 13 with a small cohort of picketers walking the sidewalk outside the Post-Intelligencer (known as the Seattle PI) building on Pine St. near 6th Avenue in downtown Seattle. Most of the initial picketers were reporters and photographers who had either been fired for affiliating with the Guild or chose to walk off the job in support of their colleagues. But before long, they were joined by longshoremen and members of the Inland Boatmans's Union who had marched up from the waterfront. The word had gone out to affiliates of the powerful Seattle Labor Council and workers from various unions made their way to Pine Street. Around noon, members of the Teamsters union arrived, and the crowd grew into the hundreds.

They chanted the slogan “Hearst is unfair to labor!." [1] This simple chant from the picketers underscored the importance of this event. The previous evening, delegates to the Central Labor Council had voted to support the Guild and declare a boycott of the Hearst newspaper. This mobilized the entire labor movement, providing leverage that the Guild had not enjoyed in other cities where it had tried to organize and win contracts.

Victory in the 105 day strike depended upon a rare combination of boldness and context. The tiny Guild local in Seattle defied the advice of Guild national leadership in declaring the walkout. Wisdom dictated caution. A strike in Milwaukee was going badly and the Guild was nearly bankrupt. But the local was angry after two members, reporters Frank Lynch and Everhardt Armstrong, were fired. Fortunately, they chose the right time and right place to be bold. Seattle had a long tradition of unionism,and the labor movement was actively rebuilding after the decimating years of the early 1930s. The little union of newspaper reporters appealed for support at a perfect moment. A year later would have been too late. Tensions between left-leaning industrial unions and more conservative unions split the labor movement in 1937. The support of the powerful Teamsters Union would not have been available one year later.

Professionals or workers?

“The journalist is nothing but a wage-earning servant, as impotent and unimportant, considered as an individual, as a mill hand." [2] So reads a quote from an editor of the Boston Herald in 1922. With a few exceptions, journalists endured poor pay and working conditions in the first decades of the twentieth century. A survey of ten well known newspapers (including the New York Times) conducted before the Great Depression had revealed the average starting salary for newspaper employees was around $176 per month. The salaries of newspaper workers had risen 30 percent from 1914 to 1928 but this was still below the cost of living, which had risen by 50 percent in the same period. In contrast, blue collar worker wages had increased their buying power by 30 percent during the same period. Working conditions were also poor. A six-day work week was common practice in the newspaper industry. In fact, the first director of the Columbia School of Journalism Talcott Williams would tell potential journalists that working 10-12 hours per day was not unusual. When assigned a news story, reporters would be expected to “stick with it” and work up to 15-hour days. Overtime pay and compensatory time off was nonexistent. Walter Howey, the managing editor of the Chicago Tribune, even threatened to cut salaries or fire reporters if they married since it was feared that family life would put too much demand on reporters’ time and take away focus from a story! [3]

There was also an inherent instability in the newspaper industry due to shakeups by management and mergers within the industry. Additionally, the low pay and poor conditions led to many reporters resorting to accepting bribes in exchange for burying, promoting, or biasing certain stories. This was especially common amongst sports writers. For example, professional boxer Gene Tunney would pay five percent of his winnings to sports writers who guaranteed him positive news coverage. [4]

Despite all this, the newspaper industry remained an attractive position for many due to an aura of romanticism surrounding the traditional newsman. The myths of this profession included the idea that journalists experienced a sense of adventure being on the “inside” covering famous issues and that was a form of compensation. These myths were promoted by veterans of the newspaper industry and editors alike. There were enough newspaper workers that accepted these myths to make the profession difficult to organize for labor. At the same time, the profession was becoming more formally educated to meet the complexity of American newspapers in the 20th century. The famous editor and publisher Joseph Pulitzer established the Columbia School of Journalism in 1912 in order to “make better journalists, who will make better newspapers, which will better serve the public." [5] However, the further professionalization of journalism would bolster the image of newsmen as white-collar workers which made labor organizing difficult due to the rarity of unionized white-collar professionals. In contrast, blue collar workers in the newspaper industry fared much better. Printers’ unions across the country had succeeded in establishing an eight-hour workday and a 40-hour work week for their members decades earlier. [6]

The first attempts at organizing among journalists started with the formation of press clubs. But these groups were formed for social purposes; there was no attempt to bargain with employers for better pay or working conditions. Nonetheless, they at least provided a template for reporters and editorial workers to organize along their professional lines. [7]

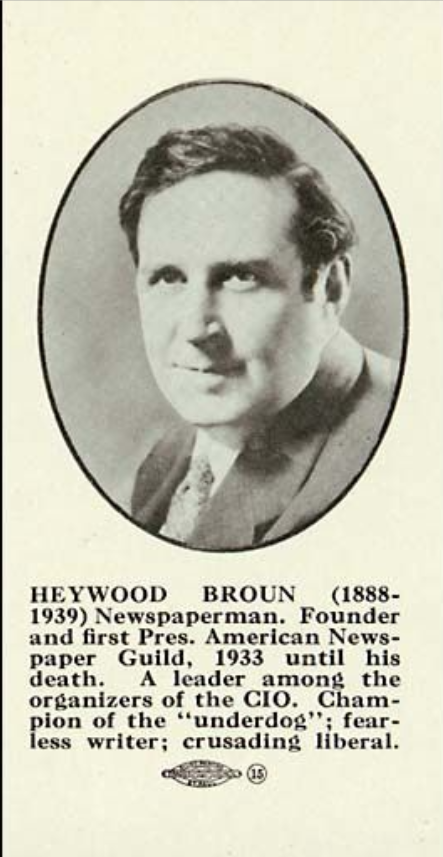

The formation of a formal union for newspaper workers would occur in 1933 in an environment of disorganization and chaos. What finally brought about the formation of the American Newspaper Guild was the attempt of publishers to fight off the attempts of the National Recovery Act to establish a minimum standard for workers. The National Recovery Administration (NRA) was a New Deal agency established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration with the objective of restoring employment, establishing pay and working standards, and preventing unfair competition and over-production. The NRA wanted all the important industries in the country to agree on a code of fair practices that established fair wages and maximum working hours. [8]

Naturally, publishers fought against this, arguing that any government interference in their industry was a violation of the First Amendment. It was at this point that editors, reporters, and photographers banded together to create guilds to ensure their voices would be heard in the formation of this code. By December of 1933, these groups would combine to form the American Newspaper Guild. [9] This newly found union would provide the impetus that would lead to the 1936 strike in Seattle.

Resurgent labor

Seattle during the Great Depression was not unlike many other parts of the country, with high rates of unemployment, business failures, and homelessness. One factor unique to Seattle was the number of seasonal jobs in the area. These included sawmills, steel and iron plants, longshoring, shipbuilding, machine shops, and fruit and fish canning. The Depression hit heavy industry hard. Steel and iron manufacturing employed nearly 60,000 workers in 1930, and this plummeted to 29,540 by 1931. Washington state’s largest industry at the time, logging and wood processing, suffered a similar drop in employment. The unemployment rate in Seattle had reached 35% before Franklin Roosevelt took office in early 1933. [10]

As the economy recovered, unions began to rebuild. Seattle had a long tradition of strong unions and labor radicalism. The Central Labor Council had demonstrated both in 1919 by shutting down the city in a dramatic General Strike. But since the mid-1920s, the Labor Council had been more cautious and conservative reflecting the leadership of Dave Beck, head of the powerful teamsters union. Leftwing unionism had revived in 1934 when longshoremen and other maritime unions won an 84-day strike that tied up all of the west coast ports. Under the leadership of Harry Bridges, the longshore union would challenge Beck and the teamsters in the years to come by affiliating with the CIO when industrial unions split from American Federation of Labor in 1937. But the split was still months away in the summer of 1936, a lucky fact for the Guild strikers. The 1936 P.I. strike would be one of the last times the entire labor movement was unified in Seattle. [11]

William Randolph Hearst

The union organizing drives that became common after 1933 threatened big business, including newspaper publishers like William Randolph Hearst, who owned the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.William Randolph Hearst was an infamous figure throughout his life. Born in 1863, he inherited the San Francisco Examiner from his father and went on to acquire the New York Morning Journal and various other publications to become one of the most powerful publishers in the country. Hearst became known for popularizing “yellow journalism” a tabloid style of reporting with little regard for truthful or well researched news and instead focused on big headlines, exaggeration, and sensationalism. In the run up to the Spanish-American War of 1898, Hearst’s publications included over the top accounts of atrocities committed by the Spanish in Cuba. When the American battleship Maine exploded in Havana harbor, Hearst’s papers blamed the Spanish which led to a war fever against Spain.

Hearst’s politics had shifted to the right over time. Once a populist Democrat, Hearst briefly supported the election of Franklin Roosevelt over Herbert Hoover in the 1932 election, but he quickly soured on the pro-labor policies of the New Deal and by 1936 his papers were publishing critical tirades against the president and left-wing politics in general. Hearst began to rally support around Alf Landon, the Republican challenger to Roosevelt in the presidential election year of 1936. [12]

Hearst purchased the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1921. By 1936, the newspaper had a circulation of 102,000 copies per day. [13] But the newspaper was one of the least profitable in Hearst’s publishing empire, and Hearst embarked on a new “efficiency” campaign at the P.I. with the focus on raising advertising revenue and cutting costs. For employees of the Seattle newspaper, that effectively meant replacing high paid employees with lower cost ones in the name of “efficiency." Bernice Reddington, the head of the home economics section of the Post-Intelligencer, experienced this firsthand. Her Prudence Penny section of the newspaper answered food questions and provided tested recipes for readers while selling advertising to grocers. Reddington was told that the budget was tight and experienced staff were being fired and replaced with younger and lower paid employees. [14] Hearst’s “efficiency” drive and his strong-arm tactics would lay the groundwork for the strike at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

American Newspaper Guild

A key figure in the strike would be Terry Pettus, an editor and reporter based in Tacoma who had joined the American Newspaper Guild in the summer of 1935. Pettus had come to the Pacific Northwest in 1927 from Minneapolis and held liberal beliefs but did not start as a radical. He worried that the Depression had revealed deep weaknesses in American society. [15] In contrast to others that joined the Guild, Pettus showed a determination to organize a local chapter for the Guild. The Tacoma chapter of the American Newspaper Guild was chartered in November of 1935.

Pettus had joined a union with little success in its short history. The union had contracts at only a few papers across Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Meanwhile, newspaper publishers fought against New Deal labor legislation tooth and nail by arguing that freedom of the press prevented the government from regulating anything having to do with the publishing industry. Publishers and their influence dominated the National Recovery Act and the National Labor Relations Board and constantly forced the union on the defensive. Although the union had managed to win back the job of one of its’ members who had been fired as a reporter for the San Francisco Call Bulletin for merely attending a Guild convention, publishers put pressure on President Roosevelt to remove the case from NLRB oversight on to the publisher friendly Newspaper Industrial Board. [16] By 1935, the American Newspaper Guild was near bankruptcy and had to stop publishing their member newspaper and stop organizing activity. The newspapers that had signed union contracts smelled the blood in the water and held off signing new agreements, some of them even ending the five-day workweek and going back to six days a week. [17] The struggles faced by the Guild meant that Pettus could count on little support from the national union leadership. Also, the fact that publishers were able to dominate New Deal labor legislation meant that strong, individual leadership would be needed to secure future union victories.

Pettus moved quickly to recruit more members to the Guild. By December of 1935, the Tacoma chapter had 22 members with ten more pledging to join. Pettus also travelled to Seattle on his only day off to try and organize a Seattle chapter. When the Tacoma Times fired a reporter that was a member of the Tacoma chapter, a strike threat from the union won the reporter’s job back, as well as recognition of the Newspaper Guild as collective bargaining agency for the Tacoma Times. This success emboldened Pettus to continue recruitment efforts in Seattle. [18]

Provocations

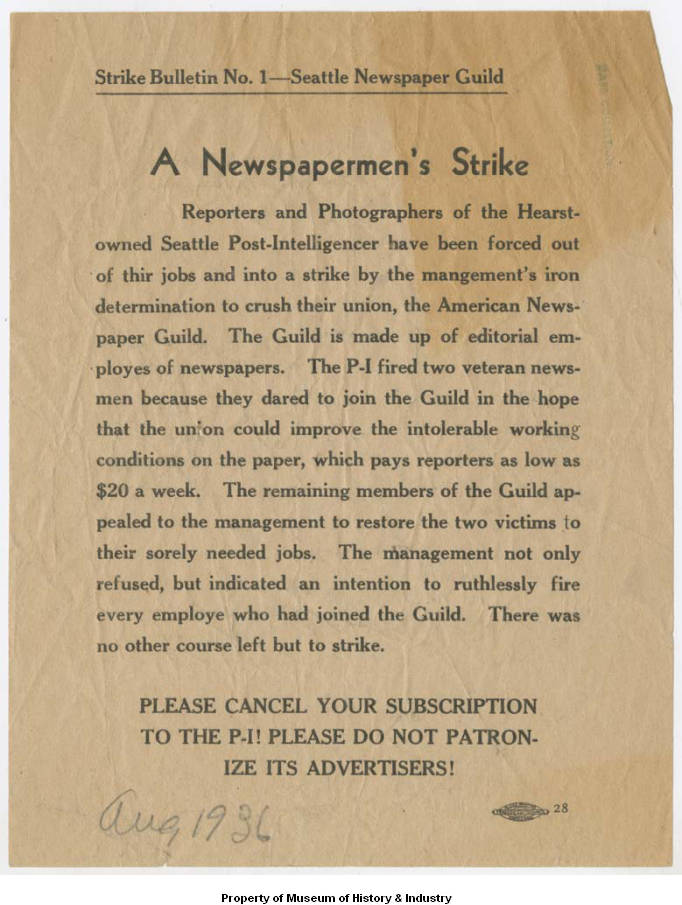

Then, on July 6, 1936, a photographer named Frank Lynch was fired from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer for signing the charter which established the Seattle chapter of the American Newspaper Guild. Tensions had been building for months at the Post-Intelligencer as management discovered the association of its’ staff with the union. During the week of Lynch’s firing, the library staff of the P.I. had admitted to joining the Guild. Hearst management at the newspaper argued that the photography unit had been disorganized and mismanaged, with old cameras, unlabeled negatives, and records that were poorly kept. This was the reason they gave for firing Frank Lynch. Lynch did not disagree with these assertions since he was out on assignment for much of his job and therefore didn’t have the time or resources to maintain an orderly photography department. But it was the timing that revealed management’s true intentions. The photography department had been in that condition for some time and received no attention until Hearst needed a reason to fire Frank Lynch for joining the Guild. [19]

Lynch promptly visited the Seattle Labor Temple to gain the support of organized labor. A resolution passed that night at the Metal Trades Union to request that the Post-Intelligencer management show just cause for the firing of Frank Lynch. The resolution would also come up for a vote the next night at the Central Labor Council and be sponsored by the left-wing metal trade union. Because the left and right-wing unions were constantly at odds with one another, this typically meant that the more powerful conservative unions led by the Teamsters would oppose such a resolution. [20] Lynch later admitted that “We were so naïve about trade unionism. I thought it was something like the Mystic Knights of the Sea. That they were all brothers, and I didn’t know there was a left wing, a right wing; believe me, I just didn’t know about it." [21] The left and right divide of the unions in Seattle, as well as the interests of the various union organizations was one of the obstacles that would be overcome in the Guild’s battle against Hearst.

Fortunately for the Guild’s cause, the resolution was passed by the Central Labor Council with the support of Dave Beck, the powerful leader of the Teamsters. Whether he saw an opportunity for a critical victory against a powerful publisher or simply viewed the case as an opportunity to build labor solidarity, Beck was willing to overlook the left and right divide amongst labor, at least temporarily. But the support from the Council was still limited. All that was being asked was for the P.I. to provide reasoning for its firing and to consider reversing the dismissal of Lynch. The Seattle chapter of the Guild remained on shaky ground as Lynch threatened to take another job and deprive the Guild of sympathy and its main cause of action against Hearst. The day after Lynch was fired, the Guild obtained six more members, bringing the total number of P.I. employees on the Guild to 35. [22]

And the union was about to obtain another cause to fight for with the firing of another reporter from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

Everhardt Armstrong was a veteran of the P.I., having been at the newspaper for 17 years. He had one of the highest salaries on the newspaper staff due to this seniority and after Lynch was fired had taken over the task of recruiting more members to the Newspaper Guild.

On July 13, 1936, the managing editor Ray Colvin asked Armstrong how long it would take to train a new employee. Armstrong responded that it would take two to three days, and Colvin then ordered Armstrong to take his vacation right away. Armstrong knew that this typically happened before an employee was fired due to similar occurrences at Hearst papers in San Francisco. Armstrong was then told his replacement would be a non-Guild member. Colvin tried telling Armstrong that he would help the paper by taking his vacation earlier but refused to guarantee that he would not be fired when he returned. Armstrong was furious at the prospect of “rats” around the P.I. newsroom, but at the urging of more cautious Guild members, agreed to take his vacation early. It was then that the management inflamed the situation when, the very next day, Colvin fired Lynch for a “defiant attitude." [23] There was now another case for the union to use against Hearst.

Meanwhile, Terry Pettus continued to organize for the Guild. He established critical connections with the various unions like the printers and typographers. Pettus also skillfully managed tensions between the left and right factions emerging within the union. When the Seattle chapter president Richard Seller requested the resignation of two members who wrote for the communist paper Voice of Action due to fear of being aligned with communists, Pettus correctly argued that their cause in Seattle would need the support of all factions of labor. Additionally, Pettus argued that nothing would be gained from dropping the members since “Our union will never please the Chamber of Commerce, the publishers, the American Legion, the Ku Klux Klan, or the Industrial Council even if we purged our ranks of every person who believed in the gospel as written by Karl Marx." [24]

In August of 1936, Pettus met with members of the Seattle, Portland, Tacoma, and Spokane chapters of the Guild to form a unified council. And, after multiple requests by the Guild, the Central Labor Council finally threatened to add the Seattle Post-Intelligencer to its’ Unfair to Labor list. This is where Pettus’s various connections came into play. The Seattle labor unions that were on the council would participate in a strike. This meant that typographers and printers would not cross picket lines to produce the paper, and the Boatman’s union and Teamsters would not deliver it. This support contrasted with the strike at a Wisconsin paper occurring simultaneously that would achieve far less results due to lack of support among the unions in that community. [25]

Guild Daily

On August 12, 1936, the Central Labor Council voted 347 to 3 to declare Hearst unfair to labor. [26] The strike had begun, and the next morning the picketers would be demonstrating outside the Seattle P.I. headquarters in downtown Seattle, with the various unions showing a united front against William Randolph Hearst and transforming the future of white-collar unionism.

The array of union solidarity behind the strike was impressive, but picketing would not be enough to resolve the conflict. One of the first tasks of the strikers involved creating a daily newspaper of their own that told their side of the story. The newspaper, called the Guild Daily, was only a few pages and included some local and national news and a sports section. However, most editions contained editorials explaining the strikers’ perspective and news about the strike. The August 14th edition of the paper includes an interesting editorial which displays the labor solidarity already felt by the white-collar members of the Newspaper Guild. In the editorial, the author describes how Guild members had disassociated themselves from the romantic notions of journalism “and began demanding enough money to pay for rent, groceries, clothing, and all the other expenses that must be met just as totally by men who work with their brains as by those who work with brawn." [27]

The Guild members had transcended the white-collar professional label that had traditionally been a hurdle to union organizing and now viewed themselves as aligned with blue collar workers to achieve the goal of better working conditions and pay. Another article criticizes how publishers had fought against unions and how those publishers had argued that it was foolish for “brain workers” to line-up with organized labor. The article also tells how the Guild had rejected affiliating with the American Federation of Labor and that this was a mistake, and “now they [the Guild] stand shoulder to shoulder with millions of workmen in America!." [28]

Once again, it appears that the strike had thrown away the veneer of romanticism in journalism and newspaper workers now viewed themselves as partners with blue-collar labor. The Guild Daily also covered the national political situation, with writer Henry Zon arguing that Republican presidential nominee Alf Landon was no friend of labor due to his association with big oil interests and financial interests on Wall Street. [29]

Editorials in the Guild Daily also blasted Hearst for his anti-labor stance and politics. Hearst was accused of being in league with Adolf Hitler and making a profit for peddling Nazi propaganda since Hearst newspapers published columns from Hitler and leading Nazi officials. And this was not altogether untrue, as Hearst had spoken positively of fascism, at one point praising what Hitler had done in Germany. [30]

Hearst could hardly complain; his own papers carried vitriolic criticism of President Roosevelt, the New Deal, and other leftist policies. An open letter in the first edition was addressed directly to the P.I. management from the Seattle chapter of the Newspaper Guild. Referring to Hearst sarcastically as the “Lord of San Simeon,” the letter sportively warned management that profit was the only priority for Hearst, and that the management would be held personally responsible if they did not deliver results. Taunting management, the letter went on to say, “This is a brief letter. You know how the “Chief” is when he gets sore. And you know where he’ll put the blame. He won’t put it on the P.I. editorial men who quit. He can’t. He’ll put it on you. You won’t like it, but gentlemen, you just can’t lump it!” [31]

The paper also answered additional local critics like the conservative owner at the Seattle Times. The Times publisher Clarence Blethen was a staunch conservative like Hearst who wrote an editorial in his paper on the day the strike started. He asserted that the city of Seattle was under siege by the threat of organized labor and put primary responsibility on Dave Beck, the powerful leader of the Teamsters whose support had helped launch the strike. Comparing Beck to a bandit, Blethen provocatively asked the citizens of Seattle “How do you like the look of Dave Beck’s gun?." [32]

Blethen feared that a small minority of people could shut down a major newspaper or any other business, noting that it was possible for one bandit could hold up a room full of people. He dramatically bemoaned the loss of constitutional government and majority rule, claiming that Seattle was now a dictatorship. [33]

Coverage of the strike in the Seattle Times focused on violence that had occurred on the first day when a guard protecting the newspaper plant named Harold Hiatt was assaulted outside the P.I. headquarters by Teamsters members. Hiatt had infuriated the Teamsters when he shot and killed union member William Usatolo during a strike at a brewing company in 1935, just a year previously. [34]

The Seattle Times focused on this assault and the occurrence of other violence on the first day of the strike. This included the physical attacks on several non-striking employees of the P.I. and general disorder. Two policemen were quoted describing “as many as 1000 men and women [who] howled and shrieked around the Post-Intelligencer building, blocking traffic." It was also reported that the police aided in evacuating P.I. employees trapped inside the building by the picket lines. [35]

Given the strong point of view expressed in Blethen’s editorial, it’s unsurprising that the Times coverage focused on portraying the strikers as violent thugs holding the city hostage with the police the only force trying to stop them. The Guild Daily offered a furious rebuttal to the Times the next day. Mocking the “tears” of Blethen, the Daily editorial argued it was Hearst who showed dictatorial attributes in firing employees without just cause. The editorial accused the Times of warping the judgment of its’ readers. [36]

The strikers’ newspaper was mostly composed of these types of editorials that propped up the union’s cause and read more like a political pamphlet than a traditional newspaper. As the strike went on, there was more of an emphasis on traditional news, but the paper never shed its’ original intent as a manifesto for the strike. The New York Times acknowledged on August 26 that “the paper is publishing more general news and has moderated the tone if its’ strike stories, although it continues to publish vigorous editorials against William Randolph Hearst and local publishers who have supported him against the strikers.” [37]

The Guild Daily would accomplish its’ task of serving as the voice of the strikers rather than becoming a traditional newspaper.

National attention

Nationally, the strike was also starting to make waves. The New York Times acknowledged the pro-labor environment of Seattle, noting how indifferent the public was to an established newspaper being forced to stop publishing due to union activity. While acknowledging that views on the strike in Seattle ran along economic and social lines, reporter Russell B. Porter stated that “if it [the strike] had happened to any other newspaper or business the public would not have stood for it for a moment, but this is such a strong union city, and organized labor here is so much opposed to Mr. Hearst, that the public did not react as it would have normally." [38]

On August 23, 1936, Porter reported in the Times that “Newspaper people here, [in Seattle] on both sides of the fence, say that this is probably one of the few and perhaps the only American city where such a thing could happen." Porter described the history of the General Strike of 1919 and how the current Seattle mayor was regarded as a labor administration. [39]

Even a national paper of record like the New York Times on the distant east coast understood that the political environment of Seattle was a critical factor in starting and maintaining the strike against the Post-Intelligencer.

Chapin Hall of the Los Angeles Times wrote an editorial on September 17 that denounced Teamsters’ leader Dave Beck as one of the most dangerous figures on the West Coast. Hall rhetorically asked how much control Soviet Moscow had over the “radicals” in Seattle and if Beck and Seattle mayor John Dore reported to the “Stalin Department of Foreign Propaganda." Hall went on to allege that this so-called radical movement of labor in the United States “found its’ first visible concentration in the Northwest, manifesting through the I.W.W., better known as the “I Won’t Work."” This editorial once again describes a unique leftist environment in Seattle that served as a perfect breeding ground for the labor movement. Hall dramatically referred to the “brood of war slackers, anarchists, and plain and fancy bums [that] continued to ferment after that organization [the Industrial Workers of the World] ceased to amount to much” [40].

Hall’s dramatic rhetoric denouncing Beck and the labor environment in Seattle ignored the divide in the Seattle labor movement and the fact that Beck was a more conservative union leader. Critics of the strike displayed a continuous habit of portraying a radical monolithic labor movement in Seattle. However, this is also indicative of how strong the labor movement was in the city compared to other places across the United States.

Additionally, the Seattle strike displayed how pressure could be applied to other news organizations around the country. The August 28, 1936 edition of the New York Times describes how the Associated Press was deprived of news coverage in Seattle since it relied on the reporting of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer for much of their information since they did not have a significant presence in the city. [41]

The Associated Press had also refused to recognize the American Newspaper Guild as a bargaining agent for its’ employees, so the Seattle strike hindering the AP’s news collection could only be seen as beneficial for other union organizers across the country in providing leverage and displayed how the strike in Seattle affected news organizations across the United States.

War of attrition

As the strike continued, the strikers settled in for a war of attrition against Hearst’s publishing empire. They established their headquarters in the Red Mill Tavern on Sixth Avenue and Union Street, which was close to the P.I. plant and allowed them to maintain an effective picket line. The Guild Daily was printed there and there were also kitchen facilities to keep the strikers well fed. This fact was understood early on when a member of the Maritime Federation known as Mrs. Dumbra advised the union that victories were not just won on the picket line and the men would have to have enough to eat. Dumbra promptly established a strike kitchen composed of the wives of Guild members. The wives were soon replaced by a former cook known as “Sparrow” who provided the meals for the entire strike. [42]In terms of financing the strike, the Seattle Guildsmen could count on little help from the national portion of the American Newspaper Guild since the union was already embroiled in a simultaneous strike in Wisconsin that was sucking up its funds and the union was on shaky ground financially to begin with. The strike thus relied on local donations from the labor organizations around Seattle. This was clearly not enough, and by the end of September, the strike had a deficit of $1600. Terry Pettus had the idea to create stamps with “Unionism or Hearst” printed on them sent all over the country, and this brought in as much as $200 a day. [43]

Also, Pettus worked to obtain funds from the Guild chapter in Tacoma amounting to $417.20. This put the strike on a stable financial footing, and although the strike would still end in a deficit of $3000, the conditions were manageable. [44]

Hearst and the management at the P.I. were also busy during the strike. Hearst had more private security guards flown in by plane to reinforce the guards at the P.I. plant, dubbed “the Angels” by strikers. There were rampant rumors that these men were heavily armed with Thompson submachine guns, prompting the Guild Daily to publish the dramatic headline “P.I. Rushes Thugs Here” headline on August 15. However, these men would never play any part in the strike. Instead, Hearst relied on a strategy so common it had its own name: The Mohawk Valley Formula. This strategy involved using scientific methods to handle strikes. The main objective involved portraying unions and their leaders as a destabilizing force and threatening to move business out of the community if union activity was allowed to continue.

Hearst made a mistake which displayed his ignorance of the Seattle labor scene. He branded all union opposition as communists in a grand conspiracy. In reality, the Seattle labor unions had left and right factions that were deeply divided. By branding Dave Beck and the Teamsters as communists just like the rest of the unions, the opportunity was missed to try and divide the labor movement. [45]

Hearst then threatened to shut down the Post-Intelligencer and conducted a ploy in which mechanics showed up at the newspaper plant ostensibly to dismantle machinery and ship it out of state, but the bluff failed. The Guild Daily celebrated the supposed Hearst withdrawal with the headline “HEARST QUITS." A Guild editorial displayed careless indifference to Hearst’s bluff, even arguing that the Guild Daily would take the P.I.’s place and bid Hearst adieu. [46]

Hearst also underestimated how much he was disliked in Seattle when 2,500 people showed up to an anti-Hearst, pro-Guild rally on August 25 where the people cheered the news of Hearst’s business leaving town. Attending the rally was the Mayor of Seattle John Dore and county prosecutor and future U.S. senator Warren G. Magnuson who declared the Guild had the full support of the Democratic party. [47]

Hearst did have the support of a few groups around the city. One of these was the Law and Order League which was led by an industrialist who argued that the rising power of labor was a threat. Another group which formed around mid-October of 1936 was the League of Seattle Housewives who picketed in front of the Labor Temple in support of the Post-Intelligencer. Only around a dozen women showed up to these protests, and none of the groups was effective in mobilizing any popular support against the strike. [48]

1936 election

The final nail in the coffin for Hearst’s cause was the United States presidential election in November. President Franklin Roosevelt defeated his Republican challenger Alf Landon in one of the most decisive electoral victories in U.S. history. Roosevelt won 60% of the popular vote and 46 out of 48 states. Hearst was forced to accept this as an approval of the New Deal and other leftist policies and accepted defeat gracefully, remarking that “The election has shown one final thing conclusively, and that is that no alien theory is necessary to realize the popular ideal in this country. All that is needed is a vigorous application of fundamental democracy and a free exercise of American rights and liberties." [49]Roosevelt’s election victory was the final push that was needed to convince Hearst to end the strike. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer formally recognized the American Newspaper Guild on November 25, 1936. This was the first time the union won formal recognition from a Hearst newspaper. A deal was finalized in which all striking employees would return to work with a 40-hour, five-day workweek with paid vacation, sick leave, and severance pay. There would be no salary reductions, and new pay scales would be implemented. However, there was no formal contract signed, and Lynch and Armstrong did not receive their jobs back, with their cases being handled separately by the NLRB. In return, the Central Labor Council removed the P.I. from the Unfair Labor list. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer resumed printing on November 29, 1936. [50]

In the aftermath of the 1936 strike at the Post-Intelligencer, the American Newspaper Guild had just 13 contracts with publishers. Just a year later, that number would jump to 45, then 90 by 1938. Guild membership had tripled by 1938. The Seattle strike was a turning point in the history of white-collar unionism. It had injected energy and momentum to a profession once considered unfit for labor organizing and had given the American Newspaper Guild new life.

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer recovered quickly from the strike in part due to a clever move by Hearst. He hired John Boettiger, the son-in-law of President Roosevelt who had married the president’s daughter Anna, to run the paper. By doing this, he conceded to the pro-labor environment in Seattle while simultaneously shrinking his profile and influence on the newspaper given the anti-Hearst sentiment shown by the citizens of Seattle.

Frank Lynch and Everhardt Armstrong’s labor cases were handled with the NLRB, and the board’s decision was announced on January 13, 1937. It was ruled that the firings had been discrimination against union organizing and ordered Lynch and Armstrong reinstated with back pay. While Lynch eventually returned to work at the paper, Armstrong died on March 18, 1937, shortly after the decision. [51]

Terry Pettus would go on to chair the Tacoma chapter’s contract negotiating committee and would succeed in generating the first city Guild contract in the United States. In 1937, Pettus’s newspaper, the Tacoma Ledger went out of business. He later worked at the Willapa Harbor Pilot paper and served as managing editor of the Washington New Dealer and joined the Communist Party in 1938. [52] Pettus had played a key role in the establishment of the American Newspaper Guild in Washington state and the ensuing 1936 strike. He and his wife were on the picket lines every week of the three-month strike.

The victory of labor over William Randolph Hearst had involved the entirety of the labor movement in Seattle. The participation of Dave Beck and the Teamsters in addition to the left-wing unions was crucial to initiating the strike and New Deal labor legislation and the overall pro-labor environment of the Depression provided a starting point for the labor movement to prosper. But even the unions needed constant nudging after the firings of Lynch and Armstrong to finally authorize the strike. Additionally, New Deal agencies like the National Recovery Administration and the National Labor Relations Board were subject to immense pressure from business interests that undermined their effectiveness in their early years.

It was ultimately the pro-labor environment of Seattle and the determination of individuals like Terry Pettus at the lowest level that allowed the victory against Hearst. President Roosevelt told his son-in-law John Boettiger “that so far as labor relations go, Seattle is without doubt one of the two or three most difficult places in the United States.” [53] These two factors combined to ensure the success of the Seattle strike and helped newspaper workers across the country shed the white-collar professional label that had hindered their drive for fair pay and working conditions.

© Copyright Ryan Seblon 2023

HSTAA 498 Fall 2022

NOTES:

[1] Ames, William E., and Roger A. Simpson. Unionism or Hearst: The Seattle Post-Intelligencer Strike of 1936. Pacific Northwest Labor History Association, 1978. Pp. 60.

[2] Leab, Daniel J.,A Union of Individuals; the Formation of the American Newspaper Guild, 1933-1936. Columbia University Press, 1970. Pp. 4.

[3] Leab, A Union of Individuals pp. 4-7

[4] Leab, A Union of Individuals pp. 8

[5] Leab, A Union of Individuals pp. 10

[6] Leab, A Union of Individuals pp. 7-10

[7] Leab, A Union of Individuals pp. 11

[8] Leab, A Union of Individuals pp. 33-34

[9] Carlisle, Rodney. “William Randolph Hearst's Reaction to the American Newspaper Guild.” Labor History, vol. 10, 1969, pp. 75.

[10] Pacific Northwest Regional Planning Commission, Migration and the Development of Economic Opportunity in the Pacific Northwest (Portland: National Resources Planning Board, Region 9, August 1939), p.95 and p. 154, Table 2

[11] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. xv-xvii

[12] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 1

[13] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 2

[14] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 6-7

[15] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 11

[16] Elmore, Cindy. “Terry Pettus and the 1936 Seattle Newspaper Strike: Pivotal Success for the Early American Newspaper Guild.” American Journalism, vol. 36, no. 3, 2019, pp. 300–321., https://doi.org/10.1080/08821127.2019.1644083. pp. 303

[17] Elmore, “Terry Pettus” pp. 304

[18] Elmore“Terry Pettus” pp. 306-307

[19] Ames, Unionism or Hearst” pp. 29-30

[20] Ames Unionism or Hearst pp. 34-35

[21] Ames Unionism or Hearst pp. 35

[22] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 34-36

[23] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 37-39

[24] Elmore, “Terry Pettus” pp. 312

[25] Elmore, “Terry Pettus” pp. 311-313

[26] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 55

[27] “Story of Guild’s National Battle.” The Guild Daily, August 14, 1936.

[28] “Guild Faces Joint Newspaper Attack.” The Guild Daily, August 14, 1936.

[29] Zon, Henry. “The Washington Scene.” The Guild Daily, August 14, 1936.

[30] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 16

[31] “An Open Letter to the P.I. Management.” The Guild Daily, August 14, 1936.

[32] “This Shameful Page.” Seattle Daily Times, 7 Home COMPLETE Final Markets ed., 14 Aug. 1936, p. 1. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current, infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A127D718D1E33F961%40EANX-1299D778AF93714D%402428395-1299CE1330922BE7%400. Accessed 3 Dec. 2022.

[33] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 68-69

[34] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 61

[35] “Violence Flares at News Plant as Guild Men Strike.” Seattle Daily Times, 7 Home COMPLETE Final Markets ed., 14 Aug. 1936, p. 1, 9. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current, infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A127D718D1E33F961%40EANX-1299D778AF93714D%402428395-1299CE1330922BE7%400. Accessed 3 Dec. 2022.

[36] “Whose is the Shame?” The Guild Daily, August 15, 1936.

[37] Special to THE NEW YORK TIMES. "Seattle Guild Strikers Curb Propaganda, Print More News in Their Daily Paper." New York Times (1923-), Aug 26, 1936, pp. 6. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/seattle-guild-strikers-curb-propaganda-print-more/docview/101638539/se-2.

[38] By RUSSELL B. PORTER, Special to THE NEW YORK TIMES. "OPINION DIVIDED ON THE P.-I. STRIKE: VIEWS IN SEATTLE RUN CHIEFLY ALONG ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL LINES. BUSINESS BACKING PAPER LABOR, LIBERALS AND RADICALS SUPPORT GUILD -- BOTH SEEK AID OF MIDDLE CLASSES." New York Times (1923-), Aug 27, 1936. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/opinion-divided-on-p-i-strike/docview/101803001/se-2.

[39] By RUSSELL B. PORTER, Special to THE NEW YORK TIMES. "P.I.' CLOSING LAID TO SEATTLE UNIONS: THEY GIVE POWER TO GUILD'S STRIKE IN CITY WHERE LABOR LONG HAS BEEN STRONG. PICKETING NEVER RELAXED HEARST PAPER BALKED IN EVERY EFFORT TO PUBLISH AS TIE-UP PASSES TENTH DAY." New York Times (1923-), Aug 23, 1936. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/p-i-closing-laid-seattle-unions/docview/101794988/se-2.

[40] Hall, Chapin. "NATIONAL RADICAL RULE SEATTLE CZAR'S GOAL: DAVE BECK LOOMS AS ONE OF MOST DANGEROUS FIGURES ON COAST." Los Angeles Times (1923-1995), Sep 18, 1936, pp. 1. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/national-radical-rule-seattle-czars-goal/docview/164620983/se-2.

[41] "A.P. SEEN AFFECTED BY SEATTLE STRIKE: DEPRIVED OF COVERAGE THERE FOR MORNING PAPERS, NLRB EXAMINER IS TOLD." New York Times (1923-), Aug 28, 1936, pp. 36. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/p-seen-affected-seattle-strike/docview/101639485/se-2.

[42] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 75-76

[43] Elmore, “Terry Pettus” pp. 313

[44] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 106-107

[45] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 77-78

[46] “Exit Mr. Hearst.” The Guild Daily, September 16, 1936.

[47] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 83-84

[48] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 85-86

[49] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 121-122

[50] Elmore, “Terry Pettus” pp. 314

[51] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 132-134

[52] Elmore, “Terry Pettus” pp. 315-319

[53] Ames, Unionism or Hearst pp. 131