In an era of American history marked by racial segregation and anti-immigrant attitudes, Washington was an anomaly as the only state in the West, and one of only eight nationwide, without laws banning racial intermarriage. During the early to mid-twentieth century, Washington was known throughout the region and the nation for its liberal social policies. Interracial couples often traveled long distances from states with anti-miscegenation laws to marry in Washington .1The National Urban League distributed a pamphlet that advertised the freedoms that blacks enjoyed in Seattle .2

This progressive legacy surely would not exist had it not been for the concerted efforts of an array of civil rights activists. When anti-miscegenation bills were introduced in both the 1935 and 1937 sessions of the Washington State Legislature, an effective and well-organized coalition led by the African American, Filipino, and progressive labor communities mobilized against the measure.

The movement against anti-miscegenation laws had two different, yet inseparable, long-term impacts on the progressive movement in Washington State . The first is obvious: it blocked legislation that would have created a precedent for other legally-mandated civil rights violations. The second effect is a bit more subtle, but equally important. In the process of disarming the anti-miscegenationists, activists uncovered their own weapon—the power of collaborative action—that would aid their charge for social reform. As they spoke with others in one voice against oppression and discrimination, each independent advocacy group found unprecedented persuasive influence. While the power of grassroots organizing was well-known, as were the prototypical benefits of populist movements, there had not been a civil rights-related effort of such scale and diversity in Washington State up until this point. In this new model for Washington State, independent actors argued on behalf of the interests of others and in the end, achieved their initial self-interested goals that had motivated them to action.

However, members of this coalition were not solely interested in their own group’s individual goals. By working together, they came to view their own struggles as interconnected campaigns in the fight for the equality guaranteed to them in America . While on the surface their desires—not to mention their lives—were often very different, at the heart of the issue and in their desire for American ideals, their goals were indistinguishable from one another. In his novel/memoir America is in the Heart, Carlos Bulosan, a Filipino activist, captured the idealistic sentiment that motivated and encouraged members of the coalition:

We in America understand that the many imperfections of democracy and the malignant disease corroding its very heart. We must be united in the effort to make an America in which our people can find happiness…We must live in America where there is freedom for all regardless of color, station and beliefs. America is a warning to those who would try to falsify the ideals of freemen… America is also the nameless foreigner, the homeless refugee, the hungry boy begging for a job and the black body dangling on a tree…We are all that nameless foreigner, that homeless refugee, that hungry boy, that illiterate immigrant and that lynched black body. All of us, from the first Adams to the last Filipino, native born or alien, educated or illiterate—We are America ! _3_

The threatened anti-miscegenation legislation put Washington’s reputation and the lives of its racial minorities at risk, giving them a stake in this legislation in numerous ways. Additionally, this legislation threatened the political influence of the state’s famously strong leftist labor organizations in their constant struggle to expand the rights and privileges of the disenfranchised. The Communist Party and some labor unions viewed this attack on minority rights also as an attack on the working class. In the name of solidarity, the labor left threw its energy behind defeating this measure.

With the Communists and organized labor beside them, the Filipino American and African American communities pressured Olympia in protest of the anti-miscegenation bills. Chinese Americans and Japanese Americans were also involved in less direct ways. The contributions and commitments of the different communities varied. In truth, all were important in what they contributed and the angle they were able to argue. In reality, none of these actors can be divorced from one another. The movement was shaped by its contributing actors—from the quiet contributions of the Chinese and Japanese communities to the strong leadership of the combined organizational efforts of the black, Filipino, and labor communities—and its success invariably hinged on the contributions of each.

1935: House Bill No. 301

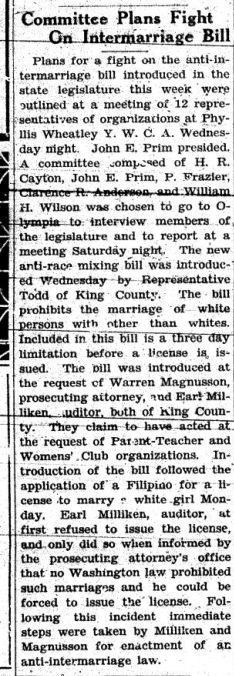

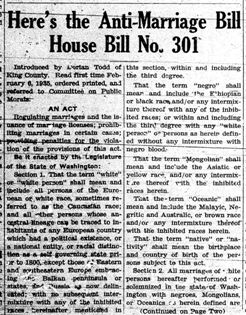

In February 1935, King County Representative Dorian Todd proposed House Bill No. 301: a prohibition on marriages of persons of Caucasian ancestry to “Negroes, Orientals, Malays, and persons of Eastern European extraction.”4 Days earlier, King County Auditor Earl Miliken received a request for a marriage license from a Filipino man and a white woman. Resolved to prevent the interracial couple from wedding, Miliken denied the request. Soon after, then-King County Prosecutor Warren Magnuson informed the auditor that there was no legal recourse to prevent the marriage. But Miliken was not to be dissuaded. Claiming to speak on behalf of the concerns of parent-teacher and women’s organizations and pleading on a case for decency, convinced Magnuson that something must be done.5Magnuson in turn proposed the bill to Representative Todd, who carried the measure to the floor of the state legislature, where it was introduced. What began as an attempt to stop a single Filipino man from marrying a white woman had quickly evolved into a movement to separate all people into racial categories that would determine who they could and could not marry. But the breadth of the bill also helped mobilize and unite a broad constituency against it. The bill never went to a vote; it was tabled by the Committee on Public Morals.6

In response to the bill’s introduction, Seattle ’s black community forged the Colored Citizens’ Committee in Opposition to the Anti-Intermarriage Bill, and chose veteran political leader Horace Cayton, Sr. as its spokesperson. The committee organized the combined efforts of Sound End Progressive Club; the NAACP; the Urban League; churches; the communist League of Struggle for Negro Rights (LSNR); the Filipino Community of Seattle, Inc.; the Washington Commonwealth Federation and the Communist Party. The ongoing efforts of the Citizens’ Committee included lobbying efforts in Olympia and hosting protest meetings at the Phyllis Wheatley YWCA and First AME Church . In addition, the Citizens’ Committee received thousands of protest letters and telegrams, which were passed onto Olympia . 7

In the black Seattle the efforts of the Colored Citizen’s committee were backed by the community’s major newspaper,, the Northwest Enterprise , and by key churches. Churches such as the First AME and Mt. Zion Baptist rallied their congregations, hosted meetings, and provided leadership. In general, churches disseminated information regarding the issue to Seattle ’s black population via their congregations. The Northwest Enterprise, on both February 7, 1935 and February 14, 1935, offered reports connecting the anti-miscegenation measure and the related churches and religious organizations working on the issue.

Announcements under the “Church Notices” section of the paper suggested the importance of the African American press and churches to the anti-miscegenation bill movement. One reported on a mass meeting of the Colored Citizens Committee at the First A.M.E.Church .8 In addition to general announcements of upcoming events, the “Church Notices” section often detailed the sermons of each church from the previous week. One such summary reported that at the morning service the congregation of Grace Presbyterian Church heard Horace Cayton offer “a plea for support to defeat House Bill 301.” Calls to action were embedded in the day-to-day announcement. For example, the above announcement regarding Cayton’s remarks was followed by this announcement: “Last Friday evening the Phyllis Wheatley Girl Reserves presented a two-act comedy at the church that was well-attended.” 9

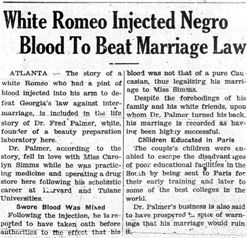

During the 1935 efforts to block the anti-miscegenation legislation, the Northwest Enterprise, covered two related nationwide stories on attempts to prevent interracial relationships, punctuating the importance of protecting the existing civil rights within WashingtonState . One article told of the extremes that others across the nation would go in order to overcome discriminatory marriage laws. Weeks after the introduction of the bill in Olympia , the paper reported on a white “Romeo” who had a “pint of blood injected into his arm to defeat Georgia ’s law against intermarriage.”10 Following the injection, the man took an oath before authorities, testifying that he did not have pure Caucasian blood, thus legalizing his marriage. The article goes on to inform readers that this “Romeo,” Dr. Fred Palmer, found good fortune in his life following this decision, that “despite the forebodings of his family and his white friends, upon whom Dr. Palmer turned his back, his marriage is recorded as having been highly successful.” Furthermore, it reported that, “Dr. Palmer’s business is also said to have prospered in spite of warnings that his marriage would ruin it.”11

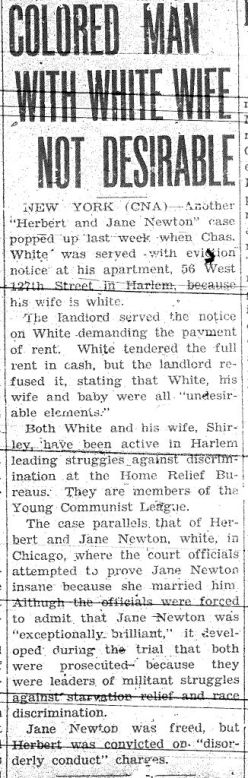

One week later, the Northwest Enterprise ran a similar front-page story; in this case a “not desirable” couple consisting of an African American man and a white woman received an eviction notice from their Harlem landlord based on this categorization.12 This article went on to highlight the parallel between this case and a case from Chicago , where court officials attempted to prove the insanity of a woman based on the fact that she had married a black man. In the end, the court officials admitted that this woman, Jane Newton, was “exceptionally brilliant.” Despite this, over the course of the trial the prosecutors developed a case against both the man and the woman based on a history of activism. The story reports that in the end the court freed Jan Newton, but convicted her husband on ‘disorderly conduct’ charges, highlighting the considerable lengths to which the government would go to prevent interracial relationships.13

Much like the Northwest Enterprise , the Philippine American Chronicle reported on the inherent flaws of the anti-miscegenation bill and the leadership of its community in the fight against it. Early in the 1935 legislative session, the paper carried an editorial, “Intermarriage Dilemma,” discussing the merits of intermarriage. Its author questioned the idea that intermarriage is “fatal” and points out that people have marriage is a risky venture regardless of race—one that individuals had freely joined for centuries. He contended that marriage should be determined by love, as it always had been, arguing,

As humans under the laws of a supreme being, irrespective of race, color or creed, we have the right to pick our mates, whether she be (sic) a white or a colored one, and nothing matters so long as both couple adore and understand one another.

Still, recognizing the complexities raised by intermarriage, the article discussed the fact that no relationship could be divorced from its environment. Intermarriage might affect standing in the public, as well as affect the treatment of their children. But, in the end, the author reassured his readers that while the social implications of intermarriage might not be easy, loving individuals should not avoid marriage because of the potential to face discrimination. He wrote, “could all the people be cosmopolitan, could the people be broadminded enough to mind their own business” they might recognize that in reality, at their heart, these people were the same, and perhaps more enlightened than most of society for recognizing this common bond despite appearances. 14

A different editorial reminded the readers of the Philippine American Chronicle that under the Declaration of Independence, the United States recognized that all men are created equal, endowed with inalienable rights that while not set in the Constitution, created an important ethic to respect and enshrine in law. The writer continued, “the pending marriage law…renders the impossibility of enforcing Americanism in the sense that it breeds sectionalism among the peoples of this country… [it] entirely deprives either party of those intending to marry of their rights to the pursuit of happiness.” Pleading to the sentiment of his readers, he writes that the United States is known throughout the world as the ‘melting pot,’ but that with laws such as the anti-intermarriage bill, “the fire that keeps the pot melting is now smoldering into ashes of insignificance.”15

Aside from editorial arguments, the Philippine American Chronicle reported on the involvement of the Filipino community in the movement against the anti-miscegenation bill, with a particular emphasis on Filipino labor unionists… Late in February of 1935, members of the Cannery Workers’ and Farmers’ Labor Union Local18257 went to Olympia to voice their opinions against the legislation. One of the delegates, himself married to a white woman and father of a son with that woman, remarked in the newspaper, “In protesting against the bill, I am prompted by its future effect not only on my son, but to others of American mothers and fathers. It would be unfair for any government to manage the affairs of one’s heart.” Another protester argued that the bill was unconstitutional in that it deprived either party of their rights in the pursuit of happiness, and that “to dictate to whom one should marry or not marry is obviously detrimental to our rights.” He commented further that the bill was “the most vicious bill ever presented in the House.”16 Upon their visit, these representatives received assurance that the bill would be defeated.17

In 1935, the Japanese American Courier followed the anti-intermarriage legislation, yet the message was separate from the coalition’s efforts, and different in nature from those of Seattle ’s other racial communities. Furthermore, in comparison to the other papers, the Japanese American Courier carried much less coverage of the anti-miscegenation bill than both the Northwest Enterprise and the Philippine American Chronicle. Where the Courier did write about the issue, it was in accord with their general practices, as the paper regularly condemned race prejudice—albeit in milder language than employed by the _Enterprise—_and called for racial understanding.18

There are several examples of this practice. The first Courier article simply reported that the bill would prohibit intermarriage and require a three-day waiting period before a marriage license would be issued. While in this report, the Japanese American weekly did not directly take aim at the legislation, the paper does address the constitutionality and ethics of the proposed legislation elsewhere in that issue. A different article recalls a statement by Dr. Inazo Nitobe, a well-known Japanese diplomat married to an American woman. The paper credits Dr. Nitobe with the perfect answer to the “problem of racial marriage.” When questioned on his own marriage, Nitobe replied, “I did not marry the race, I married an individual.” The article continues pragmatically, “The problem is not one to be regulated by law… If [those considering marriage] are resolved to face the consequences of their union, they should be commended rather than condemned for it takes not a little moral courage to face a situation which is frowned on as severely as intermarriage…such legislation is clearly discriminatory.” 19

The next issue of the Courier carried the bold headline, “Rep. Todd’s State Marriage Bill Defines Racial Groups” with smaller subheads clarifying “Caucasian, Negro, Mongolian, Oceanic Races Described; Marriages of Whites with Other Races would be Banned.”20 The remainder of the article merely reprinted the legislation as introduced, with neither commentary nor invocation of action.

Collaboration Between Progressive Whites and Minorities

The Communist Party used its newspaper, the Voice of Action, to highlight its opposition to the 1935 miscegenation bill. It set itself apart from its coalition partners by arguing that the bill was not only racist, but also anti-labor and anti-working people. One report mentioned that one month before the end of the legislative session, a mass meeting of the Citizens’ Committee received a telegram that unofficially told the group that House Bill No. 301 would be killed. The report of this event is telling on several accounts of the wider framework of action, and of labor’s self-promotion. The paper goes on to praise itself, as it writes, “it was not an accident that the telegram came to the Voice of Action, but that it clearly showed what a force the militant white workers, liberals and the intellectuals had been in the fight to smash the bill.”21 However, despite this apparent victory, the article entitled “Continued Pressure urged on Todd Bill” cautioned against giving up the fight without assurance that they had won. Before elaborating on the good news, the editors warned that rather than relying on lobbying alone, “the chance of killing the bill will undoubtedly depend upon the continuation of wide mass protest…we recommend redoubled protest as a safe guarantee that victories won to date…are not lost.”22 The Voice of Action went to great lengths to accentuate the connection between the need to fight the anti-miscegenation bill and work in common cause with white laborers. One article commented, “How Negro-hating goes hand-in-hand with labor-hating, and why reactionaries use one to split the other, was shown this week by the action of Representative Dorian E. Todd, introducer of the vicious Todd anti-intermarriage bill.”23

Following the defeat of the 1935 bill, the _Voice of Action_compared Todd and other legislators in support of the measure to a lynch mob. It congratulated its readers on their successful efforts. It also largely credited itself and militant organized labor for the victory on behalf of African Americans. The paper reported that politicians underestimated the protest that would arise over the Todd Bill, and, in plain language, stated, “The mistake these fine gentlemen made was in forgetting the Communist Party.” The article further commented, “Maybe they thought that we Communists just talk of defending the rights of the Negro people in order to catch votes, like they do. If that was their idea, they certainly know better now…the Negro people can plainly see that they have a true friend in the white toilers” again, framing themselves as the defender of African Americans.24

Some parts of organized labor utilized its already well-developed social network to spread the word to workers throughout Washington , as well as across the nation, and encouraged protest. As a result, telegrams from unemployed organizations, United Farmers Leagues, trade unions, Commonwealth Builders, leading white liberals, preeminent educators and professionals flooded Olympia from throughout the United States .25 Others contacted the Seattle Central Labor Council shortly after the introduction of the bill, urging protest.26 Likewise, Revels Cayton, prominent in both labor and African American circles, and son of Horace Cayton, Sr., the prominent leader of the Colored Citizens’ Coalition, issued a call to arms in Voice of Action that labeled the legislation as an attempt to smash unity and at the top of the report, stressed the importance with the words, “MUST ACT.” He encouraged workers to pass resolutions and send letters to the chairman of the Committee on Public Morals demanding that he kill House Bill No. 301.27

1937: Senate Bill No. 342

Two years later, in February 1937, Washington State Senator Earl Maxwell introduced a similar measure in the Senate, prohibiting marriage between Caucasians and ethnic minorities. However, Maxwell took the issue one step further and developed penalties for individuals who violate the statute. Comparing the 1937 and 1935 bills, the Northwest Enterprise commented that “Senator Maxwell has taken up the torch [from Representative Todd] and if he were to have it his way, he would burn all the bridges of progress that education, sportsmanship, interracial understanding and progressive thinking have thus far carried this state through years of steadfast advancement, unblemished by discriminatory enactment and unhaltered by Jim-Crow laws.”28 In the end, Maxwell’s bill effectively died after it was buried in the Senate Rules committee. While still in session and with the legislation pending before the committee, Lieutenant Governor Meyers met with protesters from the black community and personally pulled the original copy of the bill from the file and gave it to the delegates. Although the bill was essentially dead, handing over this version, typed and signed by the sponsor, assured that there was no remaining possibility that the bill could be enacted into law.29

Following the 1935 effort, the Colored Citizens’ Committee announced that it would continue to function to fight all discriminating laws.30 True to their word, the same organizations emerged for the second round of the fight. Seattle ’s African American community was the central player in driving the force behind the lobby in 1937.

While in the 1935 effort, the Northwest Enterprise called for action, reported on coalition meetings, and followed the status of the bill quite extensively, in 1937, the paper crusaded with fervency. Shortly after Senate Bill No. 342 was introduced, the Northwest Enterprise devoted over half of its front page to reports and comments on the legislation, calling for widespread action. Apart from the dispensing information and mobilizing blacks, the paper used articles and editorials to argue against the logic of the bill and its far-reaching, unintended consequences. One writer drew from examples of other states that had intermarriage laws “in order that all citizens may know the facts concerning such laws, and better understand why such laws are opposed.”31 Another decried the bill for “taking marriage, the most honorable institution of the human species, and putting it on a legal plan with fornication, adultery, and all the horrible sins catalogued in the Old and New Testaments. Additionally, the article described anti-miscegenation laws as “a subversion of objective morality that may have far-reaching consequence…which white and colored will reap equally.”32 The second writer questioned what constitutional rights any other person had to take the most basic of rights from another. He argued that the laws of love existed “rightly beyond the reach of humans,” and that any effort to threat these issues otherwise inherently offended the institution of marriage. Furthermore, taking on perverse laws would demoralize the people of the state and would be a “dastardly and derogatory” infliction upon true American values.33

The example of other state’s anti-miscegenation laws provided ongoing inspiration for the Colored Citizens’ Committee’s campaigns, but not always in ways one might expect. One article in the Northwest Enterprise reported that bans in other states “in spirit and effect, if not in letter, tend to make the naturally honorable relation of marriage a worse crime than the naturally dishonest practice of illicit intercourse.” This represented an effort to reclaim the language of morality and values from anti-miscegenation supporters by adopting their main argument: that relationships between people of different races are immoral. The article went on to argue that the anti-miscegenation bill promoted “the very thing it is supposed to defeat—race intermixture, by giving perfect immunity to the men of the stronger group” who could sleep with women of color but then not feel compelled to marry them or even take care of their children. This countered white fears about promiscuous men of color by arguing that promiscuous white men were the real problem to public morality, and that most people of color didn’t even want relationships with whites:

Every year, time, energy, and thousands of dollars must be spent by the Negro in the United States in opposition to this and other discriminatory laws that tend to nullify his Constitutional heritage. Not because of his desire for a mixed family, but for the protection of his own colored family…Negroes who oppose the prohibitive laws are generally already married and would not consent for their children to suffer the inconvenience which it costs to marry a white person in America , legally or illegally.

He believes that a law to compel fathers to marry the mothers would break up more miscegenation in a week than a law prohibiting marriage will break up in fifty years.34

This strategy of highlighting the protection of family and natural prevention of miscegenation as a point of agreement with their adversary is a quintessential example of political strategy focused on building a diverse coalition of support.

Aside from the Northwest Enterprise , the churches and other black organizations once again took part in the fight. For example, the NAACP, which had emerged with greater influence in the years between the bills, was an integral player in leading a multiracial coalition of 75 whites, blacks, and Filipinos to Olympia in opposition to the measure.35

The Filipino community was also once again centrally involved in the movement. In March 1937, the Philippine Advocate printed an extensive article titled, “No Race Deterioration in Mixed Marriages Says Filipino Writer.” In this article, the writer, Catalino Viado argued that interracial marriages would enhance, not detract from the quality of life in America.

There is absolutely nothing to be afraid of about interracial marriages. There will never be any race deterioration. Let us profit together by the use of our intelligence, on the right thing and in the right way. Let us exercise tolerance, using our judgment wisely without petty jealousy and race sentimentalism…Why do you worry about the security of the offsprings (sic) of white-brown marriages? When we Filipinos love, we love to the core, not artificially and superficially.”36

Second, the article contends that American society, despite all of its positive and admirable characteristics, could stand to improve. His final point is perhaps the most persuasive, and really a glimpse of the motivations of the coalition—to prevent the development of discriminatory ideas understood as truth that would naturally follow the existence of discriminatory law. He writes, “Mr. Maxwell and others say that marriage of white and black is socially ineffective. It may be so when you enact laws to make it so and educate the public about it.”37

Foundation for the Coalition

To understand the nature of this working coalition, it is important to understand the larger framework shaping minority politics and liberal politics in Washington at that time, particularly in Seattlewhich provided the headquarters for this movement. The coalition was built largely upon pre-existing ties. The diverse groups that emerged as leaders in this movement had a history of cooperation with one another, and, in addition to the wide spectrum of activism, had an important impact on the efficient and organized manner in which the coalition was able to react quickly. Likewise, looking closer at the minority and labor groups in Seattle exposes areas of disagreement that could have undermined the success of the coalition had it not been for the overwhelmingly strong ties that did maintain a solid structure.

Four distinct racial minorities—blacks, Filipinos, Japanese, and Chinese—dominated the Seattle ’s civil rights politics over the 1930s, and each group brought something different to the political table in their coalition work to oppose the bills that would have banned interracial marriage. It is significant that the original 1935 bill to outlaw miscegenation grew in response to a proposed marriage between a Filipino man and a white woman. Filipinos had a unique experience as newcomers to the United States . Thousands of Filipinos grew up under American colonial occupation, and traveled to the United Statesfor work or education not as Asian immigrants, but as American nationals.38 Upon arrival, they were quick to assume the right to vote, form unions, participate in democracy and fight those who sought to restrict their freedoms. Many racist Asiaphobes conflated this political assertiveness with sexual assertiveness, and began to complain—sometimes through violence— about “interracial liaisons” between Filipino men and white women.39 The strong community organizations within the Filipino community were well poised to counteract this racist rhetoric. In 1935, the Filipino-led Cannery and Farm Labor Union dispatched a committee of four to Olympia . Speaking on behalf of the Filipino community as well as labor unions, this committee shared with numerous legislators their opinions regarding the bill. Upon return, they dispatched information to the community through the Philippine American Chronicle and public meetings.40

But African American resistance also proved invaluable. Despite the fact that African American migration to Seattle did not grow dramatically until World War II, Seattle’s African American community was able to gain greater electoral power in the 1930s as the Democratic and Republican parties vied for their vote, as well as use these campaigns against the anti-miscegenation bills to help build up their own community and political organizations. African Americans historically voted Republican out of opposition to segregationist southern Democrats. But during the Depression, in Seattle and around the country outside the South, African Americans slowly shifted their alliances from the Republican to Democratic Party. Noting the shift to Democrats, Republican leaders in Seattle increased their support for civil rights, fair employment, and other black community concerns.41 As a small, but seemingly swayable voting block, African Americans were not to be ignored or brushed off by politicians, and this aided their lobbying efforts in Olympia .

The growing presence of African Americans in radical left-wing political groups, such as the Communist Party and the Washington Commonwealth Federation, also facilitated this growing political power.42 When the Communist Party argued that the anti-intermarriage bill was an effort by the ruling-class sought to turn the United States into a nation controlled by fascists, they sought to both move blacks away from their traditionally Republican Party ties as well as help them lead a revitalized labor movement.

Finally, black community organizations helped ensure the defeat of the anti-miscegenation bill. In addition to the Northwest Enterprise , many sectors of African American society turned to activism during the Depression—including churches, social, and political organizations. Founded twenty years earlier, the NAACP and the Urban League both were revitalized at this time as leaders and members worked to improve conditions of black life and foster the full integration of African Americans into the general society.43 The NAACP proved its capability as a legal advocacy organization through these efforts; they led the broad-based political coalition in opposition to the discriminatory policy. They also strongly committed to protecting critical community interests and maintaining the state’s support of civil rights.44

Japanese groups played a different role in the coalition. In general, Japanese intermarried with white people much less frequently than Filipinos, partially because many Japanese had arranged marriages. This shaped the way that Japanese groups participated in their opposition to the proposed ban on miscegenation.

The Japanese American Courier, the nation’s largest English-language Japanese newspaper at the time, gave coverage to incidents of prejudice and exclusion, but in much milder language and with significantly less commentary than newspapers that served African Americans or Filipinos in Seattle . 45 As previously mentioned, the Courier was not involved in the Citizen’s Committee campaign against anti-miscegenation laws. Its few reports on the topic were less likely to directly attack the racism behind the bill. While Seattle ’s Japanese population did indeed engage in the overall fight against discrimination, their leaders, including Courier editor James Sakamoto, had little tolerance for the protest strategy associated with organizations like the Seattle NAACP or Urban League. Sakamoto opposed the strong stances taken by the NAACP and advocated for accommodation to the racial status quo, educational advancement, and economic self-sufficiency. Of the Japanese, Sakamoto said they should “stay within their own community, support small businesses within their area, and emulate the patriotism of white America .”46Furthermore, there were few organizational links between Japanese and other minority groups .47 This is not to say that Japanese did not oppose the measure, but that they were not a formal part of the larger coalition that represented a wider range of activists working to suppress the bill and did not appear in force in protest of the measure.

Although Seattle ’s organized labor community had a long history of hostility to Japanese and Chinese workers, radical labor organizers included advocacy on behalf of Japanese and Chinese workers to their opposition to the bill. In an attempt to garner support, Communists argued that because Asians did not threaten public order or commit crimes, but instead set up homes, raised families, and could be characterized as thrifty and energetic, they were at risk of losing their rights. The Communists reasoned that because Asians found success and gradually assimilated to American society, they threatened the racial segregation that white employers desired.48 If assimilated Asians gained status and strength in wealth and held an expectation of rights and a hope for equality with their employers, naturally they would threaten white supremacy that helped support radically unequal distributions of wealth. According to this argument, the whites in power implemented laws such as the anti-miscegenation bill in order to prevent assimilation to American society; this tactic sought to frame the issue in the minds of others: if law stated that Asians could not be assimilated, society’s assumption would follow.

Conclusion

In the end, the development and success of this coalition built a solid foundation for political organizing in Washington State well beyond the boundaries of this specific measure. The cooperative action rooted in issues of social justice proved influential in public policy development and emboldened activists through a major victory. In the years to come the movement grew stronger because of networks established and nurtured in the fight against anti-miscegenation laws. The 1935 and 1937 campaigns laid the groundwork for future multi-ethnic collaboration on subsequent civil rights and progressive issues.

However, it must be said that while these groups developed a strong foundation for future action, they were neither strangers to organizing their communities, nor to one another beforehand. This coalition pulled together so well largely because of the preexisting ties that these interest groups and leaders had with their communities and with one another. Blacks, Filipinos, and the leftist labor movement were not strangers to one another. Filipinos drew together its community through the labor union. Blacks relied upon the social roles of churches. Both Blacks and Filipino organizations rallied their members. White labor utilized its broad networks to mobilize progressive workers state- and nationwide. Because their interconnectedness predated the actions detailed in this paper, it follows that they would be better prepared and experienced in working together for any subsequent issue that might arise following the 1935 and 1937 efforts. The fact that these groups could more easily collaborate following the efforts against anti-miscegenation is really a continuance of the same trends that brought this coalition together.

© Stefanie Johnson 2005

HIST 498C, Fall 2004

1 Takaki, Ronald, Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans, New York : Penguin Books, 1990, p. 342

2 Colbert, Robert E., “The Attitude of Older Negro Residents Toward Recent Negro Migrants in the Pacific Northwest ,” Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 15, No. 4 (Fall 1946), p. 697

3 Bulosan, Carlos, America is in the Heart: a Personal History, New York : Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1946, p. 189

4 “Here’s the Anti-Marriage Bill, House Bill No. 301,” Northwest Enterprise , February 14, 1935

5 “Committee Plans Fight on Intermarriage Bill,” Northwest Enterprise , February 7, 1935

6 “Anti-Intermarriage Bill Held in Committee”, Northwest Enterprise , March 31, 1935

7 Taylor, Quintard, The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle ’s Central District, from 1870 Through the Civil Rights Era, Seattle : University of Washington Press, 1994, p. 94

8 “Church Notices,” Northwest Enterprise , February 14, 1935, p. 3

9 “Church Notices,” Northwest Enterprise , February 7,1935, p. 4

10 “White Romeo Injected Negro Blood To Beat Marriage Law,” Northwest Enterprise , March 14, 1935, p. 1

11 Northwest Enterprise , March 7,1935, p. 1

12 “Colored Man with White Wife Not Desirable,” Northwest Enterprise , March 14, 1935, p. 1

13 Northwest Enterprise , March 14, 1935, p. 1

14 “Intermarriage Dilemma,” Philippine American Chronicle, February, 15, 1935, p. 2

15 “Americanism,” The Philippine American Chronicle, March 1, 1935, p. 2

16 “Filipino Labor Union Local Sends Delegates to Olympia ; Report Findings on Bill 301,” Philippine American Chronicle, March 1, 1935

17 “Filipino Labor Union Local Sends Delegates to Olympia ; Report Findings on Bill 301,”Philippine American Chronicle, March 1, 1935, p. 1

18 Taylor , p. 119

19 “The Marriage Questions,” Japanese American Chronicle, February 9, 1935, p. 2

20 “Rep. Todd’s State Marriage Bill Defines Various Racial Groups,”Japanese American Courier,

February 16,1935 p. 1

21 “Continued Pressure urged on Todd Bill,” Voice of Action, February 22, 1935, p.1

22 “Continued Pressure urged on Todd Bill,” Voice of Action, February 22, 1935, p.1

23 “Todd Exposed as Enemy of Labor,” Voice of Action, March 1, 1935, p.1

24 “Defeat of Todd Bill Victory of Unity Between White Workers, Negro People,” Northwest Enterprise , March 29, 1935, pp. 1, 4

25 “Defeat of Todd Bill Victory of Unity Between White Workers, Negro People,” Northwest Enterprise , March 29, 1935, pp. 1, 4

26 “Todd Exposed as Enemy of Labor,” Voice of Action, March 1, 1935, p.1

27 “Anti-intermarriage Bill is Attempt to Smash Unity,” Voice of Action, February 15, 1935, p. 3

28 “The Miscegenation Marriage Bill,” Northwest Enterprise , February 26, 1937, p. 1

29 Acena, Robert A., “The Washington Commonwealth Federation: Reform Politics and the Popular Front,” p. 154

30 “Anti-Intermarriage Bill Held in Committee,” Northwest Enterprise, March 31, 1935, p. 4

31 “Intermarriage Bill: a menace and demoralizing,” Northwest Enterprise , February 26, 1937, p. 1

32 “The Miscegenation Marriage Bill,” Northwest Enterprise _,_February 26, 1937, p. 1

33 “The Miscegenation Marriage Bill,” Northwest Enterprise , February 26, 1937, p. 1

34 “Intermarriage Bill: a menace and demoralizing,” Northwest Enterprise , February 26,1937, p. 1

35 Taylor , p. 264 (notes)

36 “No Race Deterioration in Mixed Marriages Says Filipino Writer,” Philippine Advocate, March 1937, p. 1

37 “No Race Deterioration in Mixed Marriages Says Filipino Writer,” Philippine Advocate, March 1937, p. 1

38 Philippine American Chronicle, March 15, 1935, p. 2

39 Taylor , p. 124

40 “Filipino Labor Union Local Sends Delegates to Olympia ; Report Findings on Bill 301,” Philippine American Chronicle, March 1, 1935, p. 1

41 Taylor , p. 104-105

42 Taylor , p. 105

43 Taylor , p. 95

44 Taylor , p. 93

45 Taylor , p. 119

46 Taylor , p. 131-132

47 Taylor , p. 127, 131-132

48 Cox, Oliver C., “The Nature of the Anti-Asiatic Movement,” The Journal of Negro Education, Volume15 No. 4 (Autumn, 1946), p. 614.