The memorial for Teri Bach held at New Freeway Hall (the Freedom Socialist Party’s Seattle headquarters) on a summer day in 2005 was no solemn affair. Workers, unionists, feminists, radicals, socialists and activists of every race and gender packed the house to celebrate a woman they saw as a hero and pioneer.1 Teri Bach, the first woman to become a journeyman lineman at Seattle City Light, had touched many lives. Her colleagues, comrades and family eulogized for hours on the impact she had made fighting sexism and racism on the job. How did this woman find herself in a position to affect so many individuals in a positive way? By breaking ground. In 1974, Teri Bach and nine other young women opened an entire industry to their gender.

On June 24, 1974 ten women began their first day of work at Seattle City Light, the city’s public utility. The situation was remarkable because they weren’t secretaries. As Electrical Trades Trainees (ETT) in a new City Light program, designed by long time Seattle activist and self proclaimed Marxist-feminist Clara Fraser, the women represented the first stab at gender integration of the all-male, unionized, Seattle City Light electricians. These women would become the first female linemen, sub-station constructors, cable splicers, the first unionized female utility electricians in Seattle and the first in the nation.2

They came from a variety of backgrounds. Daisy Jones, Letha Neal, Jody Olvera and Patti Wong were women of color. Angel Arrasmith, Teri Bach, Megan Cornish, Heidi Durham, Jennifer Gordon, and Marge Wakenight were white. Their ages raged from 21 years old to 36, with some of them mothers, and some not, some married, others single. Most of the trainees considered themselves feminists and a few identified as Marxists as well.3 Their past careers included waitressing, working at a laundry, as a telephone operator and driving a bus, jobs which in the 1970s were often unionized.4 Each competed against over 400 female applicants through aptitude tests and interviews to be a part of this special ten woman program.5

In addition to learning a new and dangerous trade, their bid for integration lead the ETT participants into engagement with City Light management, whose notoriously anti-union superintendent Gordon Vickery morphed from a publicity-loving ETT supporter into avowed ETT enemy halfway through the program. As well, the union that represented the women, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) Local 77, reacted to gender integration with periods of alternating resistance and assistance. All the demographics and factors that play a part in the ETT program’s history spin a story that intersects several ideological issues. Feminism, unionism and Marxism all came together to influence a project that was unique in the deliberate quality of its implementation and outcome. In comparison, many of the other women’s training programs for traditionally male trades lacked some of the social movement intersections that drove the ETT program foreward and were less effective at combating sexist backlash as a result.

Background

The history of America’s gendered labor market intertwines the cultural stigmatization of women through class and racial hierarchies. At the dawn of the twentieth century, just 20 percent of all women worked outside the home.6 Most women instead worked by raising children, doing housework, taking care of old and sick family members, doing work on their family farm and providing an often Christian ethos to the social fabric of the household. All of this support at home enabled men to work harder and longer. Women did all the domestic work to provide the market with hyper-productive male workers, not to mention the fact that they raised the next generation of workers and helped keep the family “biblewise” and conservative. These gender roles were fundamental to the economic system and were thus culturally glorified. The 19th century Fin-de-Siecle art and literature portrayed women as fragile, angelic, tender, and intimate. Women were considered clearly unsuited for working in the unrefined outside world… unless they were women of color or immigrants deemed un-American.

Through political struggle and changing markets, women began to enter the workforce at ever increasing rates throughout the 1900s. By 2003, 60 percent worked outside the home, mostly in white-collar jobs.7 The highly paid, unionized, skilled trades have been the hardest nut for women to crack. Jobs like the ones that the ETT participants struggled to succeed in fall into this category. The women organizers of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) did not themselves even see the need to for women to pursue trades work until the 1964 passing of the Civil Rights Act. Their justification was that women didn’t want access to these jobs, considered men’s jobs, because they were either too dangerous or inconvenient.8 The same excuse was used by employers to keep women out, though again race played role in this situation as well. Employers were more willing to hire minority women for dangerous “men’s” jobs and it was black women who pioneered for their gender inside the automobile manufacturing, meat packing and construction industries.9

Against the rhetoric that women were not interested in trades work lay the fact that they were aggressively discouraged from it by an industry that regarded them as less productive than men. Susan Eisenberg’s book, _We’ll Call You if We Need You10_, as well as her article on women in non-traditional fields published in _The Nation11,_ used oral histories to document that women in the trades were fired, laid-off or denied employment because of sexist stereotypes, not because they didn’t try. Male employers and workers throughout the 1970s perceived women in the trades to decrease the productivity of a crew, require more training, and supposedly reduce a project’s profitability. Eisenberg was one of the first women electricians in the San Francisco Bay Area and her oral history-based writing focuses on women’s experiences in a way that lets the stories speak for themselves. Her research suggests that if the issue is equality vs. profit, even in the short term, profit wins. Writ large, sexism (as well as racism) is good business, both in terms of paying women less than men and keeping workers divided over social issues and generally conservative.

To further contextualize the ETT program, it is also important to understand Seattle’s political climate in the early 1970s. Once called the “Jet-city,” and largely defined by Boeing’s aerospace manufacturing plants, 1970s Seattle was blue-collar and unlike the high-tech Seattle of today, with its armies of highly paid software and bio-tech professionals. A school teacher back then who asked a class, “Whose dad works at Boeing?” would see a forest of raised hands. In this labor dominated time and place, workers enjoyed a quality of life and sense of political power greatly diminished in today’s Seattle. Not yet relegated to the distant suburbs by astronomical real-estate prices or socially regimented by droning workplace routines such as 6 am start times, most Seattle workers enjoyed a lively lifestyle in the Northwest’s cultural center. At that time, workers could not conceive of having their break times monitored, their privacy violated by the degrading practice of urine testing by bosses in the name of “safety” so well known to unionized workers today.12 Seattle City Light was no exception.

Formed in 1910, Seattle City Light has employed union electricians, now represented by IBEW Local 77, since its early days. Like most AFL unions, the IBEW organized workers by their craft. The apprenticeship program that trained electricians from one generation to the next relied heavily on nepotism, with entry into the trade largely passed down between (male) family members. The civil rights movement of the 1960s helped to significantly change the way workers, especially minorities, were hired into the IBEW as well as Seattle City Light.

Coming on the heels of the civil rights movement’s intervention into Seattle’s construction industry in 1969 (see theUCWA History Project), and a militant walkout staged by City Light workers in 1974, the ETT program began in an environment charged by racial conflict, as well as worker combativeness and solidarity. The political period of the 1960s and early 1970s wasn’t just about the civil rights movement, or feminism or the anti-war movement, either. It was a time of political radicalism on all levels across the nation. Many of the white male workers at Seattle City Light were themselves wrapped up in the era’s upheavals and expressed themselves through job actions whose militancy was much greater than today’s.

Feminism quickly added itself to this charged environment. Outside of the ETT program, the first women to integrate IBEW locals in the Seattle construction trades were frequently involved in New Left political organizations. For instance: Beverly Sims worked at the Northwest Labor and Employment Law Office (LELO) and became an activist with the United Construction Workers Association (UCWA), a civil rights organization dedicated to desegregating the building trades.13 Janet Lewis, a feminist activist for women’s healthcare rights, and Sims were the first women electricians to get their journeyman’s card in IBEW Local 46.14

Starting the Electrical Trades Trainee Program for Women

In 1973, amidst this climate of radicalism and union strength, Clara Fraser was working for a federal anti-poverty program as a job skills educator. Meanwhile, Mayor Wes Uhlman, fearful that former Fire Department Chief Gordon Vickery would run against him, appointed Vickery Superintendent of Seattle City Light in an attempt to placate his rival. Ever the politicians, Vickery and Uhlman decided it would be better to voluntarily hire a few women into non-traditional trades at Seattle City Light rather than risk the type of lawsuits brought against the construction unions and contractors by black workers in the late 1960s.15 They wanted to do a training program for women and they wanted it to succeed where previous ETT programs targeting low-income and non-white male workers had largely failed in the past. Clara Fraser, who was well known for her feminist activism by this time, was recruited by Vickery to design the new ETT program.16

Fraser, born to a Socialist Party member mother and anarchist father, joined the Young People’s Socialist League (YPSL) as a teenager. As a young woman, she moved to Seattle and got a job at Boeing as electrician during WWII. Hardly the popularized American icon of “Rosie the Riveter” doing a dirty job to help the war effort, Fraser was a communist, anti-war activist and labor agitator who helped organize the 1948 Boeing strike.17 During the anti-communist witch-hunts of the McCarthy era, she was not only fired from Boeing for her politics but physically removed from the property by security and blacklisted. After being “found out” and fired from numerous union jobs in the Seattle area, she was hired as a receptionist in a psychologist’s office. When the FBI soon confronted her employers with evidence of her communism, they, unlike many other employers faced with similar intimidation, said they didn’t care because Fraser was a good employee.18 After seven years at the psychologist’s office, Fraser took a job at an anti-poverty organization and that’s where she was when Seattle City Light sought her out to design a new program to integrate women into the utility as electricians. Though the utility considered it a risk to hire on a known communist and labor leader, they chose to work with Fraser because they knew she had both the experience training minority workers and the connections inside the women’s movement necessary to make the program successful.19

As the recruiter for the first women hired to enter the electrical trades at City Light, Fraser made sure to specifically target women’s organizations for applicants. In a recent interview, former ETT participant Megan Cornish explained:

There was recently an article in Seattle Woman magazine about women in the trades that asked the question, ‘Why are the numbers of women dropping off?’ And several people, including women, were quoted as saying, ‘Well, you just can’t get them to apply.’ Well, Clara [Fraser] didn’t find it very had. She said, ‘Let’s see, women who want to be in a trade where there are no women now? It’s probably going to be women who aren’t afraid to swim against the stream.’ So she went to the feminist movement… and said, “Hey, I’m the education coordinator at City Light and we’re going to have this program so come apply.’ And over 300 women did apply.”20

Radical Women (RW) was a prominent feminist organization in Seattle’s women’s movement by the early 70s. It was a transitional organization of the “Marxist-Feminist” Freedom Socialist Party (FSP), which was founded by Clara Fraser along with her husband Richard Fraser in 1966 as a left split out of the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party (SWP).21 What gives the FSP its unique, predominately female demographic is the fact that with in a year of the young party’s inception, Dick Fraser was expelled from the organization, causing all but three of the male members to quit, and leaving the FSP as a woman-dominated Marxist-feminist organization.22 Of the hundreds who applied for the ETT program, three of those accepted were RW members. Others were affiliated with the Feminist Coordinating Council, a large coalition of feminist groups which included NOW, Radical Women, independent feminists and others.23

Other feminist organizations with goals similar to the ETT program were in effect in the 1970s but didn’t have the same quality of planning or outcomes. Mechanica, an organization formed by Gay Kiesling, started up around the same time as the ETT program with the goal of getting women to apply for apprenticeships in the exclusively male construction industry. Unfortunately, for many of the same reasons that previous ETT programs at Seattle City Light failed— such as the isolation of participants and lack of targeted training— most groups which sought to get women into building trades didn’t set their participants up for long term success.24

Fraser designed the ETT program to prepare the women for the job through two weeks of classroom and physical training. She met with many of the crew chiefs, who ran the work out in the field, and asked them what were the most important things to know before going out on the job. With this information she compiled briefings and pamphlets on basic utility electrical theory and important safety measures. To get the women closer to where they needed to be in terms of physical strength, Fraser researched the most rapid and effective means of physical training, which turned out to be swimming.25 A curriculum, which included swimming, was proposed to Seattle City Light management and accepted. Also, Fraser thought it was crucial that a significant cohort of women be hired together. The earlier ETT programs for minority men only brought in one new worker at a time. The isolation of being the only minority would often become too much and most dropped out with in six months.26 Fraser insisted the women’s ETT program include a minimum of ten trainees. In the past, the male trainees weren’t allowed to join the union until a probationary period had elapsed. This time, the trainees would be IBEW Local 77 members from day one with their own bargaining unit. Lastly, the earlier ETT programs had rules stipulating that applicants must be from a disadvantaged background, including a maximum on the years of education that they could have completed before applying. This rule was challenged so that college educated women, which many of the applicants were, could be considered if they were under-employed.27 One of the trainees had her university degree but was making $3.00 an hour working as a laundress. Both Beverly Sims and Janet Lewis had their university degrees before they joined IBEW Local 46 in the early 70’s as construction electricians and to this day a significant number of women who choose to enter non-traditional trades are already highly educated.28 29

After over a year of planning, and just weeks before the trainees were to begin the program, a fierce walkout shook Seattle City Light. 30 The issue at hand was workers’ control of their working conditions. Vickery had instituted a list of rules on worker’s conduct that many considered draconian. That two long time electricians were disciplined by the superintendent for taking a thirty minute coffee break, instead of the officially allocated fifteen minutes, set off a ten day walk-out by over 1000 Seattle City Light employees on April 10, 1974.31 During the course of this job action, which occurred just two months before the start date of the ETT program, most of the 80% female Seattle City Light clerical staff, who were not represented by IBEW Local 77, joined the walk-out. Their support was crucial to effectively shutting down the utility. The instigator of this solidarity action was none other than Clara Fraser.32Relegated to the lowest paid positions with little hope of advancement, women at the Utility had plenty to be dissatisfied with and no affection for Vickery who was brought to Seattle City Light to cut costs through wage freezes and work speed-ups.33 This 1974 “Coffee Break Walk-out” was a success. Vickery’s new set of work regulations were repealed for the time being and the workers went back on the job with a new sense of empowerment and openness. This atmosphere of unity and victory helped ease male-female tensions as the ETT women started working with the crews in the following months.34 Unfortunately, IBEW Local 77 failed its promise to organize these women workers like they said they would. The women’s solidarity went largely un-recognized and as a result many clerical workers did not support Local 77’s 1975 strike, which ended in bitter defeat.

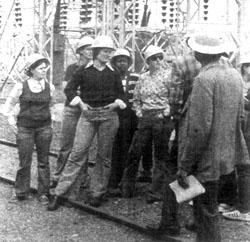

Soon after the successfully 1974 walkout, day one on the job for the trainees started with a press conference. Vickery posed with the women for a photo shoot and made grand declarations like, “any one of you could be superintendent of City Light some day.”35He also made the statement, “I won’t pretend it’s the most popular program we’ve ever had at City Light, but it’s a very important one” – hinting that hostility to integration existed among the unionized field crews. 36 In reality, according to former trainees, most of the men’s initial responses to the program and the presence of the women were positive. Fraser had made a point of ensuring that the trainees were seen as a part of the unionized workforce. The union was already indebted to her for the role she played in the walk-out and a sense of unity pervaded the workforce in those days. Male workers’ hostility was reserved for Vickery— for now.37

Yet there were minds to be changed. City of Seattle Equal Employment Officer Joan Williams told reporters that “The men on the crews, well, they’re not all stupid or sexist, but they don’t have the information in their memory banks to deal with working with women.”38 While the linemen were friendly in general, some of them didn’t believe that women could do the work. Why would women be able to? The industry had evolved in a way that excluded women and offered no provisions to accentuate women’s strengths or accommodate their physical and social differences. Megan Cornish remembers being dared by a journeyman to pull a very heavy feeder cross-arm to the top of a power pole. Never having received any training in the task, she accepted the challenge out of pride and surprised the gawking men by haphazardly rigging the arm and using all her body weight to pull it to the top of the pole instead of just her arms.39 Today women in non-traditional fields still constantly find themselves being “tested” in similar ways.

Despite the hard work of the trainees, the careful planning of Fraser and initial acceptance by union brothers, the women faced serious obstacles to successful integration from the beginning. The walkout had poisoned relations between Fraser and Vickery. Vickery took out his frustration on Fraser’s ETT program. Just a week after starting, all training was canceled by management: no more book learning, no swimming, it was out to the field ready or not. Upon getting word that their training had been canceled, most of the trainees, led by Daisy Jones, the oldest and a natural leader, marched up to Vickery’s office and demanded an explanation.40Dissatisfied with his response, they soon filed a complaint with the city’s Office of Women’s Rights saying that they were being denied the full two weeks of training that male trainees had received in previous years. The justification for paying trainees a dollar an hour less than lineman helpers, the typical entry level field position at Seattle City Light, was that what was lost in pay would be made up for in training. During the same week their training was canceled, Clara Fraser was removed from the position of Training Coordinator, costing the trainees their main advocate.41

Weeks later, an employee meeting was called by the “coffee break walk-out” leaders to rally for demands that were still unmet, including the ouster of Vickery. Most of the trainees attended, and a few made statements of solidarity with their fellow workers. They all knew that the support of the crews was vital to their success and they were better off standing together with the other workers despite their vulnerable position with management. The rally proved to be the last straw with Vickery, who called the women into the office the next week. Stating they didn’t seem very happy and were causing a lot of trouble, he proceeded to hand out a loyalty oath for each to sign promising that she would carry out any duty required by management without complaint if she wanted to keep her job.42Out of fear, a few women signed the oath on the spot but the majority of ETT participants took it with them so a lawyer could look it over. In the end, those who had not already signed added a paragraph to the document stating that by signing they were not relinquishing their constitutional rights, before submitting the signed oath to management.

After a year of working as trainees and an endless stream of political battles, most of the trainees were essentially fired. A letter went out “congratulating” them on “completing” the program and wishing them luck in future employment. So much for, “Someday you can be superintendent at City Light.” The abrupt, politically-motivated layoffs were meted out to each participant with the exception of Patti Wong, who distinguished herself as pro-management, and Jennifer Gordon, the top scoring participant on the civil service proficiency tests. Keeping a token woman or two helped divert attention from the idea that the firings had been gender-based. Jennifer Gordon, however, quit City Light soon afterwards because she felt discriminated against.43 During the same period, City Light laid off Clara Fraser, officially due to budget cuts. Seven years later, the courts determined, in a lawsuit filed by Fraser, that her termination had been more akin to a political firing.44 After the layoffs, the ETT women amended their complaint with the Office of Women’s Rights to include their dismissals.

Marxism, Feminism, and Race

The participants of the ETT program shared a sense of camaraderie because of their common situation and the fact that they spent so much time together, but they did not agree on tactics. While the voice of Radical Women certainly rang loud and clear from the program’s designer Fraser and the three active RW members (Bach, Cornish and Durham), their program was not the only set of political beliefs adhered to by ETT women. Daisy Jones, who led the women in most of their early battles, was a school teacher from California who had been involved in the civil rights movement there for years and had her own ideas. Definitely a militant, she was not a member of Radical Women. Other women in the group identified with more overtly bourgeois strains of feminism than the “socialist feminist” RW. One of the ten participants, Wong, who didn’t consider herself a feminist at all, allied with Vickery and management, and openly criticized the militancy of the program in the papers.45 The Marxist tendency inside the ETT program did, however, end up providing the glue that held the project together. With the program disbanded, the political and organizational coherence of a group like Radial Women was crucial in sustaining the political fight to get their jobs back.

Along with gender and class questions, the issue of race also finds prominence in ETT history. The experiences of the black women trainees in particular depict the inescapable centrality of racism in American history. Letha Neil, the first and only black, female cable splicer at Seattle City Light was also the last of the ETT participants to turn out of the apprenticeship and reach journeyman status. Neil was a hard worker and never made any serious mistakes on the job. Rather, she was discounted because of her race. Megan Cornish was surprised at Neil’s memorial after her recent passing in 2005 to hear so many eulogies referring to her big heart, big smile and big personality. On the job, Neil was reserved, never known to make a stink or tell a joke, perhaps never feeling like she could be herself.46 It’s no wonder considering the treatment she received as a black woman at Seattle City Light. Early on in her training, a crew chief dubbed her “the cannon ball, because she was short, round and black.”47 In another example of degrading racism from a superior on the job, as Neil walked ahead of the rest of the crew with another ETT woman her roll of black electrical tape fell out of her tool belt; her crew chief yelled, “Hey Letha, your ass-hole just fell out!”48 Race affected Daisy Jones in another way. Early on, a leader and spokesperson for the ETT participants, Daisy Jones had no trouble sticking up for herself. Constantly harassed, one day after one insult too many she shut her crew inside a job shack and locked the door.49 But when she heard the ETT participants politically targeted “layoffs” were coming after a year in the program she didn’t have the privilege of waiting around for an answer from the Department of Women’s Rights review board. A single mom of three kids, Jones had to move on to a new paycheck fast and quit Seattle City Light to take a job at King County Metro driving a bus. As a result, when the women were finally rehired, Jones was not eligible because she had technically quit under economic duress.

Racism wasn’t just used against non-white ETT women. In one instance, Teri Bach was called into Vickery’s office after an anonymous complaint from “A PO’ed citizen” who claimed he witnessed a four member crew with “a Negro and a girl” working on it. The letter claimed, “The Negro couldn’t keep his hands off the girl. In the 28 minutes I spent observing some nearby construction I noticed the Negro standing, smoking and publicly fondling the girl while the other two worked.” Bach was given a three day suspension for her refusal to cooperate with an investigation into that and another anonymous complaint. She told the Seattle Times, “I considered the charges leveled against me totally outrageous… In addition I protested the harassment inflicted on me and fellow workers by management’s repeated investigations of anonymous accusations.”50

The Battles

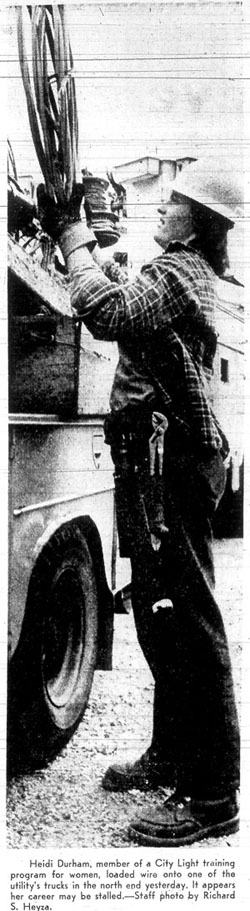

A struggle from the beginning, the ETT participants’ problems didn’t end with the termination of their program. They fought to get back the jobs they were entitled to— not just trainee positions, but the opportunity to become journeymen electricians. After adding their “lay-offs” to the previously filed complaint with the Office of Women’s Rights they took political fight to repeal the layoffs to the next level: a publicity war. In the year before the women got their jobs back, Heidi Durham remembers feeling as though there was an article in the press about the trainee women nearly every week. In fact, numerous articles were printed in both the mainstream and independent media on their case against Seattle City Light, many of which favored the women. The issue became a rallying cry for the broader Seattle women’s movement, with support coming from the Feminist Coordinating Council, an influential coalition of feminist groups. Mayor Uhlman’s unsuccessful 1976 campaign for Washington State Governor was in no way improved by the ETT scandal. While he was able to, and did, present himself as a friend to women voters in Eastern Washington, his support of Vickery against the women severely tarnished his reputation as a progressive with the much more liberal and influential voters of Western Washington.51

Less than year after their layoffs, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported July 9, 1976 that “a citizen tribunal this morning will order reinstatement of six women as electrical lineman helpers at City Light.”52 This was an astounding victory for the women who received back pay, benefits and damages that, when combined with the payment of their lawyer’s fees, totaled over $100,000.53Additionally, the six women were made eligible to begin the apprenticeship programs that City Light would be required to offer them as a part of the settlement.

While things were finally going well for the women, the male electricians at Seattle City Light sustained a painful defeat. A 1975 strike ended on management’s terms, with not a single union demand met. Not only would the six women return to a job with sub-standard wages compared to utility workers in the rest of the state. They were also joining an angry workforce whose recent defeat stood in marked contrast to the women’s victory.54 Heidi Durham recalled that “they were angry because we fought and we won, and they fought but they lost.”55 In addition, Vickery was so upset at being forced to rehire these women— who he regarded as traitors and agitators— that he deliberately set them up in situations where they were assured failure, and in one case paved the way for to Durham’s life-threatening workplace injury.

After the rehire, the remaining six women were allowed to apply for apprenticeships. Typically a few different programs are available at Seattle City Light, but that year only the most physically strenuous one, the lineman’s apprenticeship, was made available. The three RW affiliated women, Bach, Cornish and Durham were the only ones to apply. Heidi Durham was no frail girl. The youngest and strongest of the group, she was a natural for the job. Yet Vickery deliberately set her up to fail by putting her on a crew with a known racist and sexist bigot (Frank Caraback) as its chief. 56 Part of a crew chief’s responsibility is to evaluate the quality of an apprentice’s work on a monthly basis and submit a review to management. In addition to the sexist remarks and lack of appropriate training Durham was subjected to, she repeatedly received poor reviews that didn’t accurately represent the quality of her work. One day, under a tremendous amount of pressure to perform, she was working as fast as she could climbing up and down power poles while her journeyman worked off a bucket truck across the street. In those days, linemen were not allowed to use a safety harness because it was too slow and instead “free-climbed” the poles. On the way down the pole Durham’s boot hit a knot in the wood and bounced off. She lost her grip, fell 28 feet and landed in a sitting position.57

“Her accident was very much due to the persecution she was facing on the crew she was on,” remembers Cornish, who was working on a pole across town when the accident happened. “I remember that the lineman on my crew that was the most hostile to me came up to me at the top of the pole I was working on, in his bucket truck and said, ‘I hear your friend fall down, go boom.’ Heidi had just broken her back. It still makes me furious, that S.O.B.”58

Lying in the hospital, where she spent months and was initially told she would never walk again, Durham began to wonder what her union, IBEW Local 77, had to say about the accident. The official safety report blamed her for the accident, essentially, she recalled, because she didn’t listen to the advice of her union brothers and get out of the trade. After reading this, a furious Durham encouraged Bach and Cornish to attend the next union meeting and demand that the report be rescinded. Their motion failed.59

Hostility to the women electricians had grown both in the union and workplace since their return. After Durham’s injury, it was open season on the rest of them and the torment increased palpably. But the opposition they encountered wasn’t total. Eventually a committee of seven Local 77 brothers re-opened the issue of the report. Again the motion lost, this time by a narrow margin. The women felt the only thing left to do to combat the union’s bigotry would be to sue. But they didn’t out of principle, deciding “It was not worth it.”60 IBEW Local 77 was, after all, their union despite its immense flaws. Perhaps through their Marxist understanding of capitalism, they decided not drag the organization that represented their class interests through the courts.

Meanwhile, Clara Fraser was battling Seattle City Light to get her job back on the charge that she was discriminated against due to her sex and political beliefs by Vickery and City Light management. In 1982, after a seven year fight buoyed by a favorable ruling by Seattle’s Human Rights Department, a $30,000 dollar settlement that was later revoked by the City Council, and a two year appeal process that finally landed the case in Superior Court, Fraser got her job at City Light back. In addition, she won $53,000 in back pay and damages, plus 12 percent interest, plus attorney fees for a total of $135,265.14.61

The Outcomes

On one hand, the success of the ETT program can be measured by the rate of retention and career progress seen by its participants. Unlike the building trades, women have fared somewhat better in in City Light. While many of the young women who go into construction trades view the experience as positive step in their careers, or a way to learn some major life lessons and make a bit of money before they move on to other things,62 most of the ETT participants stayed in the industry and ended up retiring from City Light. Construction electrician Janet Lewis in some way is the exception that proves the rule. Lewis spent time as a contractor, L & I inspector and lawyer but essentially never left the trade and is today a Business Representative for IBEW Local 46.63 However, as of the Summer of 2006, no woman construction electrician has ever retired from Local 46 with the 30,000 hours needed to collect a full retirement.

The women who participated in the ETT program fared much better. Megan Cornish, who never saw herself as particularly suited to line-work, became the second woman power station operator at Seattle City Light soon after Durham’s injury, continuing in a union job that entails performing switching operations at the sub-stations to rout the power on the lines. (Joann Simmons holds the title for first power station operator, which actually made her the first field worker as well because she started working in the Skagit long before ETT program. Simmons was a pioneer, but she was also an anomaly.) Despite a dramatic recovery from her injury, Heidi Durham never returned to the physical level necessary for line-work. Seattle City Light offered her an administrative position but she refused, insisting that they find a place for her in the field earning the wages she was accustomed to. She eventually joined Cornish as a power station operator before moving on to become the first woman power dispatcher, a position of significant authority and responsibility. The power dispatcher ensures that a power line is de-energized before a line crew works on it. Surely more than one lineman who had abused her in the past learned the lesson that good union workers do not hurt their sisters and brothers, as they began work on a line that they had to trust she had de-energized.64 Teri Bach worked as a journey lineman until her neck was broken in a horrific industrial accident. A large tree limb fell directly onto her head as she worked in a bucket truck miles outside the city. She knew that she had been seriously hurt and that if she moved her head it would be the end, so she and a brother from the crew held her head still until they arrived at the hospital. After her recovery, she became City Light’s first woman cable splicer. While working on a downtown underground crew, she met her future life partner, Gordon Hamilton, and taught him a thing or two about the world.65

Eventually the women also received a modicum of recognition from the union. No ETT participant ever became a union official, but occasionally when they needed someone who would really stand up for a member during a grievance process, especially if the issue of gender or race was involved, the union would look to one of the RW members in particular.66 At the time of their retirements, IBEW Local 77 held a special ceremony for the ETT participants thanking them for their groundbreaking work and long records as good union members. The plaques they were presented with were addressed to, “Our Very Own Radical Socialist Bitches” referring to an incident when a bigoted union official was busted calling the women that in the late 1980s. After hearing of their “nickname”, they showed up at the next union meeting with boxes full of “Radical Socialist Bitch” buttons and by the time the meeting was brought to order nearly every union member in attendance was sporting one.67

Yet despite the positive legacies of the women’s struggles, the ETT program failed because the industry was never opened to more than a handful of women. The first ETT program for women in 1974 was also the last. Seattle City Light was willing to let a few women into the trade, but was much less interested in challenging the sexist culture that thrived there or engaging feminists on a continuing basis. No other woman was hired by the utility for nearly ten years after the program began, until, in the midst of Fraser’s case to get her job back, Radical Women started to push the issue of female hiring as well. Eventually the city’s Office of Human Rights became involved and that helped open the door up again. Yet the women have never enjoyed more than token representation in the utility trades, never exceeding eight percent of the total workforce according to one estimate.68

Though RW had pushed to get City Light to hire more women in the early 1980s, the women City Light hired after the termination of the ETT program had different agendas than many of the original ETT participants. With the women’s rights movement of the 1970s in decline, they tended to be less interested in the explicit goal of challenging sexism and more interested in making a good living. Cornish recalls that the second wave of women to work at Seattle City Light were not activists. They would try to fit in and be “one of the guys” and often the friendliest women were the first to be driven out.69 Durham remembers an occasion when she was a power dispatcher and a new batch of lineman helpers was brought in to get a tour of dispatch, and one woman in the group approached her and thanked her for her pioneering role. This was unusual, however. New women hires generally got a lecture from someone on their crew to the effect of, “Stay away from the ETT women. They’re trouble.”70 This kind of warning sent a message to new hires that they would not do well, or perhaps would not be respected by their work teams, if they continued the activism that the ETT women pioneered.

Despite the heroic efforts of the program’s participants attempting to de-segregate the industry, there hasn’t been much actual progress since then. The same can be said for the pioneering women in the unionized construction trades whose numbers nationally hover in abysmally low 1-3 percent range.71 It’s as if the door closes behind every woman who manages to open it, never open long enough for a critical mass of women to enter the trade and change the workplace culture, and leaving the women who make it in dire isolation. Yet women have broken into many other male dominated industries. Once upon a time, nearly all occupations were strictly male and now the majority of American women work outside the home. What is it that has made gender integration so difficult in these highly paid unionized trades? Perhaps it is that these jobs are highly paid and, because of their union contracts the wages are not very susceptible to degradation. Often when women enter a job field, “colonization” occurs, a phenomenon in which men leave , the job becomes predominately female, and wages plummet. A classic example is the field of gynecology. What used to be a highly paid medical specialty lost its prestige after being opened to women. Now male doctors are more apt to seek a higher paid specialty such as cardiology or plastic surgery which hasn’t been opened up.72 A capitalist market economy has no interest in integrating its workforce unless there is a profit incentive. Employers rarely want to open up traditionally male-dominated jobs to women except to drive wages down. This has the double effect of excluding women from some of the best-paid jobs, as well as pressuring feminist movements into fighting with male workers for a piece of a shrinking pie.

Another reason why women have not succeeded in the electrical trades despite integration efforts is that the attempts have not focused on significantly changing the trade to accommodate women. Concrete cultural and physical obstacles stand in the way of women wanting to pursue a career as an electrician. After all, no reason exists why most healthy women wouldn’t succeed as electricians, and even flock to the well-paid trade, with proper accommodation. For instance, hurdles such as the inability to match work hours with daycare availability could be remedied by more a more flexible work schedule or at-work child care facilities. Paid leave for pregnant women and new mothers and fathers would allow women to work and have families regardless of their personal situation. And of course any comprehensive health plan would need to cover abortion. The gap in physical strength between some men and some women could be surmounted by changes in material designs to favor lighter, easier to work with materials, or by the advancement of tool technology, or by simply having workers pair up for more physically challenging tasks. This would no doubt decrease the incidents of injury among male workers as well. Different reproductive health issues between men and women, such as the amount of lead, mercury, radioactive materials and other toxins a person of reproductive age can safely be exposed to, should also be held to the highest standard. Just because a man might not be as likely to father a disfigured or mentally retarded child because of toxin exposure does not mean that exposure is healthy. The reason for the continuation of all these factors that discourage women from joining the electrical trade is that making the changes to nullify them would interfere with profit. Ultimately the responsibility for ensuring these changes lies with the union leadership. It is their duty to represent the interests of the working class against the interests of the bosses on an economical level.

Integrating the utility and building trades presents a challenge to the union leadership. It cannot be an either/or situation. Their responsibility is to both defend working conditions, like wages, and make the trade materially, socially and culturally accessible to workers regardless of gender or race. Unfortunately, that’s not what they did in the 1970s and it’s not what they’re doing now. Clara Fraser’s explicit understanding of the profit system, with her perspective on union culture and the needs of minorities, gave her an advantage in implementing a successful albeit limited integration program which the average trade union official lacks. Or as Heidi Durham put it in a recent interview, “Organized labor has a tremendous role to play but we can’t accomplish it with the current leadership of the AFL-CIO. The ones who want to please business and government are the ones who are holding us back.” More, better and continuous ETT programs may not be enough to fully open the trades to women, but the movement inside Seattle City Light that happened as a result of the ETT program is definitely worth emulating.

Copyright © Nicole Grant 2006

HSTAA 499 Winter 2006

1 Teri Bach Memorial Video, Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project Collection. July 24, 2005.

2 “Women Enter the Electric Circuit.” Seattle Times, June 25, 1974.

3 Heidi Durham, interviewed by Nicole Grant, November 7, 2005. durham.htm

4 Erin VanBronkhorst. “Women Trained for Electrical Trades.” Pandora, Vol. 4, No. 15, July 1974

5 Ibid.

6 Professional Women: Vital Statistics, AFL-CIO Department for Professional Employees Fact Sheet 2004, Last accessed at http://www.pay-equity.org/PDFs/ProfWomen.pdf, May 5, 2006

7 Ibid.

8 Dorothy Sue Cobble, The Other Women’s Movement: Workplace Justice and Social Rights in Modern America. (Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, 2004) p. 187

9 Ibid., p. 71

10 Susan Eisenberg. We’ll Call You If We Need You: Experiences of Women Working Construction, (Ithaca: Cornell Press, 1998).

11 Susan Eisenberg. “Women Hard Hats Speak Out.” The Nation, Vol. 249, No. 8, p. 272

12 Mark Grant, interviewed by Nicole Grant, April 18, 2006.

13 Nicole Grant. “The History of Seattle’s Electrical Workers Minority Caucus in the Labor Movement.” Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project. EWMC.htm

14 Janet Lewis, Interviewed by Nicole Grant, April 13, 2006. janet_lewis.htm

15 Durham interview.

16 Cornish interview.

17 Clara Fraser; Introduction by Joanna Russ. Revolution She Wrote, (Seattle, Red Letter Press, 1998)

18 Cornish interview.

19 Durham interview.

20 Megan Cornish, intervew by Nicole Grant, October 20, 2005. cornish.htm

21 “The Legacy of Richard S. Fraser, Revolutionary Integrationism: The Road to Black Freedom.” Workers Vanguard, No. 864, February 17, 2006.

22 A Victory for Socialist Feminism: Organizer’s Report to the 1969 FSP Conference, Second Edition (Seattle: Freedom Socialist Party Publications, 1976)

23 Durham interview.

24 Lewis interview.

25 Cornish interview.

26 Durham interview.

27 Suzanne Schilz. “City Light Short-Circuits Sex Bias.” Pandora, Vol. 4, No. 12, March 19, 1974.

28 Beverly Sims. Interviewed by Nicole Grant. May 25, 2005. sims.htm

29 Lewis interview.

30 For more information about the walkout at City Light, see this oral history at historylink.org.

31 Don Tewkesbury. “History of Coffee Break Case.” Seattle PI, April 13, 1974.

32 Cornish interview.

33 “City Light Women in Low Paying Jobs.” The Seattle Times, October 24, 1974.

34 Cornish interview.

35 Ibid.

36 “Women Enter the Electric Circuit.” Seattle Times, June 25, 1974.

37 Cornish interview.

38 Schilz. “City Light Short-Circuits Sex Bias.”

39 Cornish interview.

40 Durham interview.

41 Katie Robinson. “City Light Trainees Fight Layoffs.” Pandora, Vol. 5, No. 11, October 1975.

42 Cornish interview.

43 Debby Lowman. “Court Told City Light Training Favored Men.” Seattle Times, April 20, 1976.

44 Maria Taylor. “City Light Switches Speed on Layoffs.” Seattle Sun, August 13, 1975.

45 Lee Moriwaki. “Sparks Fly Over Training Program.” Seattle Times, August 8, 1975.

46 Cornish interview.

47 Durham interview.

48 Cornish interview.

49 Durham interview.

50 Lee Moriwaki. “Sparks Fly Over Training Program.” Seattle Times, August 8, 1975.

51 Durham interview.

52 Maribeth Morris. “Reversal For CL on Women.” Seattle PI, July 9, 1976.

53 “$100,000 Payday for City Light Trainees” Seattle Times, December 14, 1976.

54 “Tuai Supports City Light Workers Wage Demands.” Seattle Times, October 23, 1975.

55 Durham interview.

56 Cornish interview.

57 Durham interview.

58 Cornish interview.

59 Durham interview.

60 Ibid.

61 Janet Sutherland. “The Politics of Persistence.” Freedom Socialist, Vol. 8, No. 1, Fall 1982.

62 Sims interview.

63 Lewis interview.

64 Durham interview.

65 Teri Bach Memorial Video.

66 Durham interview.

67 ibid.

68 Cornish interview.

69 ibid.

70 Durham interview.

71 Barbara Byrd. “Women in Carpentry Apprenticeship: A Case Study.” Labor Studies Journal, Vol. 24, No. 3, p. 3, Fall 1999.

72 Naomi Barko. “The Other Gender Gap.” American Prospect, Vol. 11, No. 15, June 19, 2000.