During the Ku Klux Klan’s revival during the 1920s, the organization formed a strong presence in the Pacific Northwest. In Washington, the majority of the Klan’s work was devoted to passing an anti-Catholic school initiative and attempting to spread their particular brand of white, Protestant supremacy. Yet while Oregon passed an anti-Catholic school bill in 1922, heavily backed by the Oregon Klan, Washington voters rejected a similar measure–and the influence of the Washington Klan–two years later. This paper argues that the reason the bill, known as Initiative 49, did not pass in Washington State is, first of all, poor timing. Because it was placed on the ballot two years after the passing of the Oregon bill in 1922, the United States Federal Court had moved in the interim to declare the bill unconstitutional. The initiative also failed because it faced strong opposition, not only by Washington Catholics, but by many other powerful groups. The Federal Court’s ruling on the Oregon bill, the strong opposition to the initiative by powerful groups in Washington politics, and the negative press reported by the majority of Washington newspapers combined to doom Initiative 49 in Washington State and to greatly limit the Klan’s ability to grow by the late 1920s.

The Ku Klux Klan that surfaced in the 1920s formed the second wave of Klan activity in the United States. Unlike the first emergence of the Ku Klux Klan, formed in the South in 1868 and mainly concerned with keeping black people from exercising their new freedoms, the second wave of the Ku Klux Klan focused their efforts on a wider range of issues. This new wave portrayed themselves as a race-protecting group that “espoused a virulent form of racism, anti-Semitism, anti-Catholicism, and anti-immigrant sentiment.”1 Secondly, they saw themselves as “moral, law-abiding citizens dedicated to political and civil reform, civic improvement, and the defense of traditional American values.”2 The second Ku Klux Klan also differed from the first in that it was spread out all over the United States. The Pacific Northwest was home to a large Klan membership, and for a few years in the early 1920s, Klan members were active in the Oregon State government.

The Ku Klux Klan first came to the Pacific Northwest in 1921, appearing in the Oregon towns of Medford, Klamath Falls, and Tillamook.3 The Klan was brought to Oregon by Luther Powell, a Klan organizer who had worked in California and Louisiana. Powell visited Medford in January to scout out new areas where he could start new branches of the Klan, called “klaverns.” During his stay in Oregon, with the help of a local named P.S. Malcolm, Powell formed Oregon’s first klavern of 25 members.4 Medford’s klavern was quickly emulated in other parts of the state. As Klan members reported, “The Oregon Klan had 14,000 members including the mayor of Portland, many politicians, and police officers.”5 The members of the Ku Klux Klan saw themselves as “real” Americans and protectors of what they saw as the American way of life. Due to their sense of duty, the Klan targeted groups that were not like the majority of white Americans and attacked them. The Oregon School Bill was one way in which they did this.

The Oregon School Bill aimed to close private Catholic schools in Oregon and have the children sent to the public school system. Since public schools taught state-mandated curricula, the Klan saw this measure as a way to “Americanize” Catholic children and limit the amount of “non-Protestant” instruction they received. Oregonians who supported the Compulsory Education Bill, including the Oregon Klan, made the argument that private and parochial schools were often controlled by non-American organizations that emphasized foreign ideologies over traditional American values.6

It’s plausible that, since a majority of Oregon’s population was Protestant, that there was some pre-existing hostility toward Catholics that could explain the support for, and eventual passage of, the explicitly anti-Catholic measure.7 However, the determining factor does not seem to be religious hatred as much as the large Klan following in Oregon. Not only were there 14,000 members in the state by the early 1920s, but there was an even larger swath of citizens sympathetic to Klan ideas and propaganda. The Klan’s anti-Catholic propaganda campaign in the Northwest led to the formation of a few new groups targeting private and parochial schools on anti-Catholic grounds, including the National League for the Protection of American Institutions, which expressly hoped to guard the public schools against Catholic ideology.8 Backings from other national organizations like the National League provided the Klan with the guidelines they needed to help them craft the Anti-Catholic School Bill in 1922.

The Oregon Compulsory Education Bill was initiated not by the Klan, but by the Scottish Rite Masons, an anti-Catholic fraternal organization who hoped its passage would act as a model for other states to follow.9 The Oregon School Bill required every child between the ages of eight and sixteen to attend public schools in their districts, assimilating immigrant children into American (and Protestant) institutions. The Klan supported the bill as a legislative tool they could use to promote their hatred of Catholics, and shifted attention away from the fact that the Bill would close all private schools and focused on the perceived threat of Catholicism to Oregon’s public schools.10 The Masons shared the Klan’s nativist ethos, and saw the bill as a way to stop immigrants and ethnic communities from forming “foreign” organizations and schools in the United States.11

Opponents of the bill stressed the amount of money it would cost to carry out the mandate. Funding for public education comes out of the state budget, and it would fall to Oregon taxpayers to pay for the costs of more schools, buses, books, and other supplies necessary to accommodate all of the students who previously attended private schools. As historian M. Paul Holsinger writes,

“The bill’s opponents also tried to appeal to the voter’s pocketbooks. Pointing out that there were over 12,000 students in the state enrolled in private schools, the initiative’s foes argued that the inclusion of these children in the public system would mean an addition of millions of dollars from increased taxes to pay for their education.”12

Another argument against the bill was that children in private schools received “more personal attention, often from better educated teachers, than they did in the state’s schools.”13 Opponents also argued that the bill was an “infringement of the constitutional freedoms guaranteed to all Americans.”14 This was an argument made against the Washington bill two years later, and was the basis for the lawsuit testing the constitutionality of the Oregon bill after it was passed in 1922. Despite the arguments of its opponents, however, the Oregon Compulsory School Bill was passed in November 1922. The bill was to take effect in 1926, and plans were made to start closing all the private schools in Oregon and begin moving children into public schools.

After the passage of the bill in November, action was taken almost immediately to test the law’s constitutionality. On January 15, attorneys representing the Hill Military Academy of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary argued for an injunction against Oregon’s Governor Pierce, Attorney General Van Winkle, and District Attorney Myers.15 The plaintiff’s argument was that the law “is now causing damage to the plaintiffs because patrons of their schools are already seeking schools in other states and the plaintiffs are prevented from carrying out improvements required by the normal development of their schools.”16 A week later, new arguments were filed in the brief: first, that the bill violated the constitution of the state of Oregon, Section 20 of Article IV; and second, that it would introduce undue economic hardship to Oregon taxpayers to accommodate the new ruling. 17 After three months, the Federal Court ruled unanimously that the new law be declared void, on the grounds of violating the United States Constitution, basing their decision on the fourteenth amendment to the Constitution which guarantees the liberty of schools to teach and the right of parents to enroll their children where they wish.18 The bill was then taken to the United States Supreme Court, who also ruled it unconstitutional, although not before Washington voters voted on Initiative 49 in 1924.

The initial success of anti-Catholic organizing in Oregon motivated the Klan to spread into Washington and see if similar legislation could be passed there. The leader of the Ku Klux Klan in Oregon, Luther Ivan Powell, moved to Washington in order to organize a strong Klan force in the state, declaring himself King Kleagle of Washington and Idaho.19 Due to Powell’s efforts, there was an increase in Klan membership in the state and the subsequent drafting of Initiative 49, modeled after Oregon’s School Bill. Unlike in Oregon, in Washington, the Ku Klux Klan themselves drafted the bill and put it on the ballot; the measure was often referred to as the, “K.K.K. Anti-School Bill.”20

Like the Oregon bill, the language of the bill’s presentation was deceiving, omitting the enforced closures of private schools that would occur and mentioning only the requirement of public schooling until age sixteen, exemplified in this 1924 article in the Seattle Daily Times:

This is a measure initiated to the ballot by petition. It is an act compelling children between the ages of 7 and 16 years to attend public schools. The measure makes it mandatory that parents and guardians of children between the ages fixed in the act send these children to the public schools for the full time such schools shall be in session.21

To those not reading closely, it seemed only to require children to be schooled full-time through their sixteenth year, not seeming to mention the subsequent closing of all private schools. Too, though the Klan was motivated by anti-Catholic nativism, the language of the bill makes no mention of it.

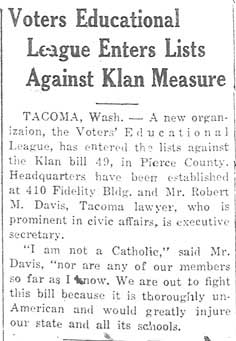

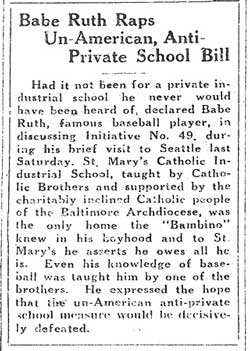

Despite the potentially deceiving language, there was strong opposition to the initiative, leading to the bill’s eventual failure in Washington. A large amount of the opposition was led by the Catholic Northwest Progress, a newspaper that kept the Catholic community apprised of the proceedings of the Oregon bill through the Federal Court and of Klan efforts to pass a similar measure in Washington. The Progress explicitly called out the Klan’s anti-Catholic motivation, and acted as a galvanizing force for opposition to Initiative 49, bringing together major newspapers in the State, Catholic and Protestant clergy, mason organizations, labor groups, the mayor, and other state officials.

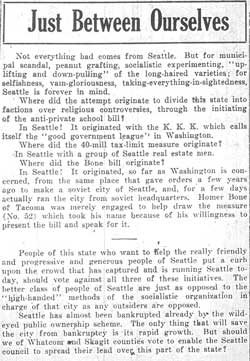

It was not just the Catholic Northwest Progress that opposed Initiative 49, but most newspapers in Washington: reported the Progress in January of 1924, “Newspapers of Washington were practically unanimous in condemning the action of the five Tacoma men who last week filed a petition for an initiative bill in which the destruction of freedom of education in this state is proposed.”22 Further, newspaper officials renewed their pledges of unity at the annual press association, held at the University of Washington’s School of Journalism. The President of the Washington Press Association, Chapin D. Foster, reported the Progress, “has declared his opposition to the proposed initiative measure advocated by the Ku Klux Klan for the destruction of private schools in the state of Washington.”23Foster and other leaders of the press went on to say that putting Initiative 49 on the ballot in November would destroy the unity which the press of the state had been working on in Washington, and marked that the only newspapers editorializing in favor of Initiative 49 were either Klan-controlled or pro-Klan.24 The unity of the press was essential to Initiative 49’s failure, as their articles likely swayed many voters’ opinions.

Another group that stood up against the bill was the masons. This was significant, since the Scottish Rite Masons in Oregon were the people who first petitioned for an anti-Catholic school bill in Oregon. As the mason’s statement read,

Catholics of the State of Washington are not alone in the fight against the Initiative 49 which is proposed to destroy private and parochial schools; hundreds of Masons will ask no higher privilege than to give of their efforts and of their time and of their money to defeat this iniquitous, false and unfair bill which is subversive of constitutional guarantees and is aimed at the liberty of our country.25

Lutherans and Adventists were also against the passing of Initiative 49 because of its infringement on religious liberties.26 The protection of religious liberty was important to all of the religious groups of Washington, and was protected by the First Amendment in the United States Constitution. As the masons, Lutherans, and Adventists realized, the passing of Initiative 49 would have been detrimental to more than just the Catholics, for if passed it could have led to other initiatives targeting other religious groups in Washington.

Labor organizations, like the Seattle Central Labor Council, also opposed the initiative, arguing that it attacked “fundamental liberties” and restricted the ability of parents to raise their children in the way they saw fit, following the stand taken by the American Federation of Labor on the issue.27 The Labor Council adopted a resolution opposing the Klan’s attempt to place the measure on the ballot, and went further in denouncing the Klan’s efforts to “stir up strife and dissension” by pushing the anti-Catholic initiative.28 The support of non-religious groups, such as the Labor Council and American Federation of Labor broadened the opposition to the initiative to include civil, as well as religious, liberties.

That so many different groups in Washington opposed this initiative is vital to the fact that it did not pass. Not only were different religious groups, both Catholic and Protestant, coming together in opposition to the bill, but there was also a strong voice from other groups that had no religious affiliation. Along with the labor and newspaper groups opposing the initiative, the large cities of Spokane, in eastern Washington, and Tacoma, in western Washington, took stands opposing the measure. Reported the Catholic Northwest Progress in June of 1924, “Spokane Citizens are organized to fight Ku Klux Klan Bill. Two thousand workers volunteer—withdrawals come in rapidly.”29 A month later, the paper reported that the people of Tacoma also rallied together in support of the fight against Initiative 49.30 These are just a few of the main indicators of widespread opposition to the bill before it was voted on in November.

The only real backer of Initiative 49 in Washington was the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan argued that public schools and public education were the “nurseries of democracy,” and children in private schools were learning to place loyalty to foreign institutions above loyalty to the United States. Further, they argued that parochial school instruction was harmful to children, and that the schools have “failed to keep step with the progress of society in Spain, France, Italy, South America, Mexico, and in the United States. Where they rule, the percentage of illiteracy and ignorance is on the increase.”31

The Washington Klan also argued that the Oregon bill that was ruled unconstitutional and Initiative 49 were completely different. The Klan contested that Oregon’s “decision was rendered by the lowest Federal court in that State,” and that, “no court save the United States Supreme Court can finally construe the Federal Constitution.”32 They also argued that the wording of the two bills was completely different, and that the main problem with the Oregon bill was not the thrust of its legislation, but the particulars of its wording.33

The Ku Klux Klan faced a lot of hardships throughout their campaign of Initiative 49 in Washington. Despite their arguments, the fact that they were the only backer of the measure and a known terrorist group did not help the initiative’s chances of winning broader support. Not only did they face a strong opposition force by different groups throughout Washington State and the nation, but they also had internal problems that hindered their ability to work well together and present a united front to the public. After the filing of their petition to get Initiative 49 on the ballot in November, the press reported that the Klan had gathered many of the signatures needed to file the petition under false pretenses. Several articles in the Catholic Northwest Progress were devoted to exposing this: one headline stated that, “thousands declare circulators of Klan Bill deceived them. Exposure of fraud to continue.”34 One example of people signing under false pretenses was when “two negroes appeared at the City clerk’s office, demanding that their names be withdrawn. One had been induced to sign by a Klansman who said he had the ‘Bone Bill’. The other Negro said he was asked to sign if he wished every child to have an education.”35 This is just one example of many of these deceitful methods of the Klan to get the measure approved for the ballot, and speaks to the Klan’s inability to win most people to their nativist, supremacist program.

In the months leading up to the election on November 4, 1924, there was a sharp increase in activity opposing the bill and urging voters to vote against it. On August 1, it was announced that Initiative 49 would be on the ballot in November.36 As soon as August 15 there were advertisements in the Catholic Northwest Progress urging all people who were not registered voters to register before the deadline. One article began, “REGISTER!! Every citizen who has not registered since January 1, 1924, should REGISTER IMMEDIATELY,” and ended with, “If you have not registered since January 1, 1924, DO NOT FAIL TO REGISTER BEFORE THE BOOKS CLOSE NEXT TUESDAY.”37 Another article that appeared in the paper a couple of weeks later read, “An Important Duty. YOU, Mr. and Mrs. Citizen, have an important duty to perform next Tuesday, September 9. You must cast your vote in the primary election…it is the privilege and the duty of every citizen to vote.”38The closer the date came to November 4, the more direct the articles telling voters to vote down Initiative 49 became.

Northwest newspapers lived up to the “unity of the press” they had agreed upon a few months before. The _Catholic Northwest Progress_had articles with headlines that read “A Treacherous Ballot Title,” and included a facsimile of the ballot, clearly marked “no,” on the page.39 The Seattle Daily Times also had articles telling people to vote against Initiative 49. In the Daily Times’ advisory ballot, the newspaper had the following advice for how to vote for Initiative 49: “Initiative Measure No. 49—the Ku Klux Klan Bill—VOTE AGAINST. The title of this bill is deceptive. The purpose of the bill is to destroy all private schools. Increase taxes and deliver the government of the State of Washington into the hands of a secret society.”40 There was also a paid advertisement from the Friends of Educational Freedom, which said “INITIATIVE 49 Would Injure Public Schools. Vote “AGAINST”. Initiative 49 would INJURE THE PUBLIC SCHOOLS FINANCIALLY by decreasing the amount now available for educating each child in public schools.” The article ended by adding that “Initiative 49 is condemned by the National Education Association, by business men, labor organizations and by ministers of all Protestant denominations.”41 These articles show the widespread, and often strong, opposition to the bill.

The headline on the front page of the Catholic Northwest Progress on November 7 read, “WASHINGTON DECISIVELY DEFEATS KLAN BILL.”42 The votes for the initiative were as follows: 131,691 for the initiative to 190,823 against. While the initiative was voted down by a little over 59,000 votes, in some counties and cities it was decisively closer. Eight of the thirty-nine counties in the state voted for the initiative, and in seven of the counties (including four of the counties that passed the bill), the vote for or against was within a margin of one hundred votes. The counties that passed the initiative were: Adams County, Chelan County, Cowlitz County, Douglas County, Grant County, Grays Harbor County, Wahklakum County, and Whitman County. The counties in which the vote was decided by a margin of one hundred votes or less were largely rural counties: Cowlitz County, Franklin County, Grays Harbor County, Lewis County, Mason County, Wahklakum County, and Whitman County.43 In the cities of Kent and Auburn, the vote was also quite close: Kent, a major center of Klan activity, passed the measure by 416 to 399, and Auburn passed it by a similarly close margin of 795 to 675.44

The decline of the Ku Klux Klan came rather rapidly after 1924, and not only in Washington State. Klan membership, while it remained high in Whatcom County, dropped considerably after the defeat of Initiative 49 in Washington State. Throughout the United States, the Klan also lost a big majority of its members, largely because of national scandals and corruption of its leadership. The Klan faced a huge decrease in the size of its secret society, going from over two million members to only a couple hundred thousand within a year.45Too, the Immigration Act of 1924 sharply restricted immigration to the United States based on a regressive and unwieldy quota system that limited immigration to 2% of that race or nationality’s population according to the 1890 census and excluded East Asians and Asian Indians completely. 46 Though Klan activity in Washington had centered on anti-Catholicism, the Act nationally neutralized one of the Klan’s main platforms for recruitment, namely, the threat of large-scale immigration.47

The internal conflicts among members of the Klan and public scandals involving its leadership added to its decline in the mid-1920s. The Ku Klux Klan from the beginning was a corrupt organization, where its leaders cared more about personal gain than from the benefits of the organization as a whole, despite the organization’s preaching about living a corruption-free life. Also, the loyalty to the local group far outweighed the loyalty to the national organization, which made it hard for national leaders to exercise control and consistency of the group as a whole. It also led to factions of the group breaking off and forming groups similar to the Klan, which the Klan did not tolerate. The corruption from the top since the beginning led to many public battles, which did not bode well for a secret organization like the Klan. As historian David Chalmers writes,

Almost invariably internal disputes brought a flurry of charges and countercharges in the press and in the courts. Not only was it harmful to the Klan to have its dirty linen always being washed in public, but the spectacle of a secret, terrorist organization settling its internal problems in court was not one to inspire fear or respect.48

A perfect example of corruption from the top happened in 1927 when, as reported by the Southern Poverty Law Center,

A group of rebellious Klansmen in Pennsylvania broke away from the invisible empire and [Imperial Wizard Hiram Wesley] Evans promptly filed a $100,000 damage suit against them, confident that he could make an example of the rebels. To his surprise the Pennsylvania Klansmen fought back in the courts and the resulting string of witnesses told of Klan horrors, named members and spilled secrets. Newspapers carried accounts of testimony… and the enraged judge threw Evans’ case out of court.49

In general, the nature of the Klan as a violent, secret organization with little national power as an organization and a corrupt and power-hungry leadership led to its ultimate decline during the mid-to-late 1920s. In Washington State, the defeat of Initiative 49, combined with the scandals, worked together to reduce the Klan’s size and power drastically.

Initiative 49 in Washington and the anti-Catholic bill in Oregon are an example of how far some groups will go to force their ideology onto others. The Ku Klux Klan wished for all children between the ages of seven and sixteen to attend public schools in their district because they believed that this would assimilate the Catholic children into proper Americans and stoke anti-Catholic fears among a wider layer of people who could be won toward Klan ideas. Yet by the time the bill was proposed in Washington, the Klan faced a strong coalition of forces, bringing together labor, religious, governmental, and media organizations in the state. That the Klan could not put together a similar coalition of forces in support of the bill shows their inability to win broad layers of supporters to their political program and anti-Catholic ideology. This coalition, combined with the Federal Court’s ruling against the Oregon School Bill, combined to defeat the Klan’s initiative and to hinder the dissolution of the Klan in Washington State.

Copyright © 2006, Kristin Dimick

History 498B, Fall 2006

1 David Norberg, “Ku Klux Klan in the Valley: A 1920s Phenomena,” White River Journal (January 2004), White River Valley Museum, WA: [http://www.wrvmuseum.org/journal/journal_0104.htm].

2 Norberg, “Ku Klux Klan in the Valley,” 2.

3 Francis Paul Valenti, The Portland Press, the Ku Klux Klan, and the Oregon Compulsory Education Bill: Editorial Treatment of Klan Themes in the Portland Press in 1922 (University of Washington, 1993), 68.

4 M. Paul Holsinger, “The Oregon School Bill Controversy 1922-1925,” Pacific Historical Review, no.37 (1968): 333.

5 “Document #8. The Bitter and the Sweet: Minutes from the LaGrande KK Meeting, January 26, 1923.” [http://libraries.cua.edu/achrcua/OSC/document8.htm], August 18, 2005.

6 Valenti, The Portland Press, 86.

7 Valenti, The Portland Press, 83

8 Valenti, The Portland Press, 84.

9 Valenti, The Portland Press, 85.

10 Valenti, The Portland Press, 86.

11 Valenti, The Portland Press, 87.

12 Holsinger, “The Oregon School Bill Controversy,” 333.

13 Holsinger, “The Oregon School Bill Controversy,” 333.

14 Holsinger, “The Oregon School Bill Controversy,” 333.

15 “Action Started to Test Validity of Oregon Law, Hill Military Academy and Holy Names Ask Injunction,” Catholic Northwest Progress, January 18, 1924.

16 “Action Started to Test Validity of Oregon Law, Hill Military Academy and Holy Names Ask Injunction,” Catholic Northwest Progress, January 18, 1924.

17 “New Arguments in Amended Brief Filed at Portland,” Catholic Northwest Progress, January 25, 1924.

18 “Strong Decision Upholds Parental and School Rights,” Catholic Northwest Progress, April 4, 1924.

19 Ryan Kuttel, Preserving Public Morality: The Ku Klux Klan of Washington and their Anti-Catholic School Bill, (Bellingham: Western Washington University, 2000), 15-16.

20 “Father of Anti-School Petition Drops Dead in Home,” Catholic Northwest Progress, February 8, 1924.

21 “Problems Voters Must Decide,” The Seattle Daily Times, November 2, 1924.

22 “State Press Condemns Ku Klux Efforts to Stir up Hatred,” Catholic Northwest Progress, January 18, 1924.

23 “Washington Newspaper Men Renew Pledge to Promote Spirit of Unity,” Catholic Northwest Progress, March 14, 1924.

24 “Washington Newspaper Men Renew Pledge to Promote Spirit of Unity,” Catholic Northwest Progress, March 14, 1924.

25 “Masons will Oppose Anti-School Bill,” Catholic Northwest Progress, May 16, 1924.

26 “Lutherans and Advents Oppose Ku Klux Measure,” Catholic Northwest Progress, March 7, 1924.

27 “Labor Council Opposes K.K.K. Anti-School Bill,” Catholic Northwest Progress, May 23, 1924.

28 “Labor Council Opposes K.K.K. Anti-School Bill,” Catholic Northwest Progress, May 23, 1924.

29 “Spokane Organized to Fight Klan Bill,” Catholic Northwest Progress, June 20, 1924.

30 “Tacoma to Carry on in Fight on Klan School Bill,” Catholic Northwest Progress, July 4, 1924.

31 Britton, “Arguments,” 5.

32 Britton, “Arguments,” 5.

33 Britton, “Arguments,” 5.

34 “Publication of 350 Names Leads Many to Withdraw,” Catholic Northwest Progress, June 6, 1924.

35 “Publication of 350 Names Leads Many to Withdraw,” Catholic Northwest Progress, June 6, 1924.

36 “Klan Anti-School Bill will go on November Ballot,” Catholic Northwest Progress, August 1, 1924.

37 “REGISTER!” Catholic Northwest Progress, August 15, 1924.

38 “An Important Duty,” Catholic Northwest Progress, September 2, 1924.

39 “A Treacherous Ballot Title,” Catholic Northwest Progress, September 9, 1924.

40 “Shortest, Safe Way to Vote,” Seattle Daily Times, November 2, 1924.

41 “Initiative 49 Would Injure Public Schools Vote ‘AGAINST’,” Seattle Daily Times, November 3, 1924.

42 “Washington Decisively Defeats Klan Bill,” Catholic Northwest Progress, November 7, 1924.

43 J. Grant Hinkle, Washington Secretary of State “Abstract of Votes Polled in the State of Washington at the General Election Held November 4, 1924.”

44 Norberg, “Ku Klux Klan in the Valley,” 7.

45 “Document #8. The Bitter and the Sweet: Minutes from the LaGrande KKK Meeting, January 26, 1923.” [http://libraries.cua.edu/achrcua/osc/document8.htm], August 18, 2005.

46 Mae Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton Unviersity Press, 2004), ch. 1.

47 Ngai, Impossible Subjects, ch. 1.

48 Chalmers, David M. Hooded Americanism: The History of the Ku Klux Klan. (Durham: Duke University Press, 1987), 296.

49 Southern Poverty Law Center. “A Hundred Years of Terror,” [http://www.iupui.edu/~aao/kkk.html], 2001.

Copyright © 2006 Kristin Dimick

History 498B, Fall 2006

1 David Norberg, “Ku Klux Klan in the Valley: A 1920s Phenomena,” White River Journal (January 2004), White River Valley Museum, WA: [http://www.wrvmuseum.org/journal/journal_0104.htm].

2 Norberg, “Ku Klux Klan in the Valley,” 2.

3 Francis Paul Valenti, The Portland Press, the Ku Klux Klan, and the Oregon Compulsory Education Bill: Editorial Treatment of Klan Themes in the Portland Press in 1922 (University of Washington, 1993), 68.

4 M. Paul Holsinger, “The Oregon School Bill Controversy 1922-1925,” Pacific Historical Review, no.37 (1968): 333.

5 “Document #8. The Bitter and the Sweet: Minutes from the LaGrande KK Meeting, January 26, 1923.” [http://libraries.cua.edu/achrcua/OSC/document8.htm], August 18, 2005.

6 Valenti, The Portland Press, 86.

7 Valenti, The Portland Press, 83

8 Valenti, The Portland Press, 84.

9 Valenti, The Portland Press, 84.

10 Valenti, The Portland Press, 84.

11 Valenti, The Portland Press, 85.

12 Valenti, The Portland Press, 86.

13 Valenti, The Portland Press, 87.

14 Holsinger, “The Oregon School Bill Controversy,” 333.

15 Holsinger, “The Oregon School Bill Controversy,” 333.

16 Holsinger, “The Oregon School Bill Controversy,” 333.

17 “Action Started to Test Validity of Oregon Law, Hill Military Academy and Holy Names Ask Injunction,” Catholic Northwest Progress, January 18, 1924.

18 “Action Started to Test Validity of Oregon Law, Hill Military Academy and Holy Names Ask Injunction,” Catholic Northwest Progress, January 18, 1924.

19 “New Arguments in Amended Brief Filed at Portland,” Catholic Northwest Progress, January 25, 1924.

20 “Strong Decision Upholds Parental and School Rights,” Catholic Northwest Progress, April 4, 1924.

21 “Strong Decision Upholds Parental and School Rights,” Catholic Northwest Progress, April 4, 1924.

22 Ryan Kuttel, Preserving Public Morality: The Ku Klux Klan of Washington and their Anti-Catholic School Bill, (Bellingham: Western Washington University, 2000), 15-16.

23 “Father of Anti-School Petition Drops Dead in Home,” Catholic Northwest Progress, February 8, 1924.

24 ”Father of Anti-School Petition Drops Dead in Home,” Catholic Northwest Progress, February 8, 1924.

25 “Problems Voters Must Decide,” The Seattle Daily Times, November 2, 1924.

26 “State Press Condemns Ku Klux Efforts to Stir up Hatred,” Catholic Northwest Progress, January 18, 1924.

27 “Washington Newspaper Men Renew Pledge to Promote Spirit of Unity,” Catholic Northwest Progress, March 14, 1924.

28 “Washington Newspaper Men Renew Pledge to Promote Spirit of Unity,” Catholic Northwest Progress, March 14, 1924.

29 “Masons will Oppose Anti-School Bill,” Catholic Northwest Progress, May 16, 1924.

30 “Lutherans and Advents Oppose Ku Klux Measure,” Catholic Northwest Progress, March 7, 1924.

31 “Labor Council Opposes K.K.K. Anti-School Bill,” Catholic Northwest Progress, May 23, 1924.

32 “Labor Council Opposes K.K.K. Anti-School Bill,” Catholic Northwest Progress, May 23, 1924.

33 “Spokane Organized to Fight Klan Bill,” Catholic Northwest Progress, June 20, 1924.

34 “Tacoma to Carry on in Fight on Klan School Bill,” Catholic Northwest Progress, July 4, 1924.

35 Ben H. Britton et al, “Arguments on Behalf of Proponents of Initiative Measure Number Forty-Nine”, filed on July 17, 1924, in the State of Washington Pamphlet for the November 5, 1924 election, compiled by Secretary of State J. Grant Hinkle (Olympia: Frank M. Lamborn, 1924), 5.

36 Britton, “Arguments,” 5.

37 Britton, “Arguments,” 5.

38 Britton, “Arguments,” 5.

39 “Publication of 350 Names Leads Many to Withdraw,” Catholic Northwest Progress, June 6, 1924.

40 “Publication of 350 Names Leads Many to Withdraw,” Catholic Northwest Progress, June 6, 1924.

41 “Klan Anti-School Bill will go on November Ballot,” Catholic Northwest Progress, August 1, 1924.

42 “REGISTER!” Catholic Northwest Progress, August 15, 1924.

43 “An Important Duty,” Catholic Northwest Progress, September 2, 1924.

44 “A Treacherous Ballot Title,” Catholic Northwest Progress, September 9, 1924.

45 “Shortest, Safe Way to Vote,” Seattle Daily Times, November 2, 1924.

46 “Initiative 49 Would Injure Public Schools Vote ‘AGAINST’,” Seattle Daily Times, November 3, 1924.

47 “Washington Decisively Defeats Klan Bill,” Catholic Northwest Progress, November 7, 1924.

48 J. Grant Hinkle, Washington Secretary of State “Abstract of Votes Polled in the State of Washington at the General Election Held November 4, 1924.”

49 Norberg, “Ku Klux Klan in the Valley,” 7.

50 “Document #8. The Bitter and the Sweet: Minutes from the LaGrande KKK Meeting, January 26, 1923.” [http://libraries.cua.edu/achrcua/osc/document8.htm], August 18, 2005.

51 Mae Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton Unviersity Press, 2004), ch. 1.

52 Ngai, Impossible Subjects, ch. 1.

53 Chalmers, David M. Hooded Americanism: The History of the Ku Klux Klan. (Durham: Duke University Press, 1987), 296.

54 Southern Poverty Law Center. “A Hundred Years of Terror,” [http://www.iupui.edu/~aao/kkk.html], 2001.