“Oust Seattle Enemy Aliens” read the _Seattle Star_’s front-page headline on February 16th, 1942. It was just over two months since the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of war with Japan, and local sentiment ran high against local Japanese and Japanese-American residents. The Seattle Star, a popular daily newspaper published from 1889-1947, provides an excellent window into the question of how such strong anti-Japanese sentiment arose in the months between the attack on Pearl Harbor and the issue of Executive Order 9066, which established the federal wartime internment camps. This essay examines the Seattle Star from December 1941 through February 1942, focusing on the Star’s reaction to key events such as the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the issue of Executive Order 9066 and, in particular, on the paper’s hostile and sometimes racist portrayal of native Japanese and Japanese-Americans, especially after the paper was sold in January 1942. By analyzing letters to the editor during these months, this approach also allows us to discover the local non-Japanese population’s views on the war and the idea of internment.

II. Background

The Seattle Star was a locally owned paper, first published on February 2, 1899. In 1909 it was sold to the E.W. Scripps family. Then, in January 1942, it was sold to Howard W. Parrish, a one-time employee of the Star. It ended publication on August 13, 1947 due to increases in labor costs and a shortage of newsprint. Recently, another paper under the same name began print but there is no connection to its namesake. Although it did not have as large a staff, circulation, or readership as the Seattle Post Intelligencer or the Seattle Times, the Star still managed to reach people throughout King County as evidenced by, among other indicators, the locations of writers to the editor.

In December 1941 Japan was a nation full of desire for national power, respect, and supremacy. It wanted to achieve equal footing with the Western Powers and revise the unequal treaties that it had signed with those nations in the past. Following the precedent of Europe and the United States, it began to industrialize in the late 19th century and was the dominant imperial power in Asia by the early 20th century. Historian Kenneth B. Pyle has implied that because of Japanese ambitions and the overall climate of militarism of the 1930s in both Europe and Asia, the “road to the Pacific War” was one that could not be have been avoided.

Pyle also shows how the anti-Asian racism that would be thrust to the surface by Pearl Harbor had deep roots. Racial tensions first began to develop on the United States western coast between white Americans and Japanese immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1905, the California legislature unanimously passed a resolution calling on the government to limit immigration, characterizing Japanese immigrants as “immoral, intemperate, quarrelsome men bound to labor for a pittance.”1 The next year the San Francisco School Board created separate schools for all children of Chinese, Korean, or Japanese descent.

Japan understood these measures to imply that the Japanese were still not on equal footing with the Western powers. They felt that, as an industrialized nation, their nationals should not be grouped with people from China or Korea. In the aftermath of World War I, US President Woodrow Wilson had tried to appease the Japanese by allowing them to write an equality of races clause for the League of Nations charter, which would read “that the principles of equality of nations and the just treatment of their nationals … [shall be] a fundamental basis of future international relations in the new world organization;”2however, the measure was never voted on.

From Japan’s perspective, the last insult from the United States came when Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924. This act is also known as the Japanese Exclusion Act since it plainly states that although immigrants from other nations would still be admitted on a revised quota system, no more Japanese immigrants would be admitted to the United States. This, coupled with America taking a protectionist stance after the stock market crash of 1929, caused Japan to turn further inward and focus on the consolidation of its own economic, political, and military sphere in Asia and the Pacific.

In the 1930s Japan built a strong military government fueled by militant nationalism. The invasion of Manchuria and its transformation into Manchukuo led to censure by the League of Nations, which Japan then abandoned. It decided to control East Asia and spoke of an “Asian Monroe Doctrine” and later a “Greater East Asian Co-prosperity Sphere.” In his book War without Mercy, John Dower argues that Japanese thinking was characterized by an “intense self-preoccupation” that emphasized Japanese virtue and purity.3 Japanese citizens made sacrifices for the whole to prove their loyalty and spiritual commitment to the nation. They felt Americans were materialistic and egocentric due to their upheld values of capitalism, individualism, and liberalism. Thus, Japan began its drive towards joining the Tripartite Pact and entering World War II.

On December 7, 1941, Japan not only attacked the US fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor but also the Philippines, Wake Island, Guam, Malaya, Thailand, Shanghia, and Midway. US citizens were outraged since peace talks between the United States and Japan had been taking place in Washington. The US felt that it had been patient with Japan in awaiting its answer as to why it had been increasing its forces in Indochina. When America declared war on Japan on December 8, so too did many other countries, including Britain and Canada. China followed suit on December 9. Japan countered by invading the Philippines on December 10 and also seizing Guam. By the end of December the Japanese Imperial forces had also invaded Burma, British Borneo, Hong Kong, and Luzon. General Douglas MacArthur began to withdraw from Manila to Bataan, and the British surrendered Hong Kong. Although the Japanese were giving a tough battle, sentiment remained strong that the US would prevail. Locally, some people were very upset about others not following black out procedures.4 But on the whole, in Seattle and throughout the nation, the attack on Pearl Harbor united Americans in common cause. One Seattle Star reader summed up the result of the bombing of Pearl Harbor like this:

A nation divided within itself; a nation torn with abor strife; a nation shouting from two camps – isolationist and interventionalist; a nation whose people were wailing about increased taxation; a nation of Democrats and Republicans; a nation bickering over all-out aid to Britain or all out home defense… thanks to Japan the United States are again one nation, indivisible.5

II. The Seattle Star: December 1941

The size of the Japanese presence in Seattle, as in most of California and Oregon, caused local residents no small amount of anxiety once war broke out between the United States and Japan. It is this anxiety, turned suspicion and fear, that a close analysis of the Seattle Star in the months after Pearl Harbor allows us to glimpse.

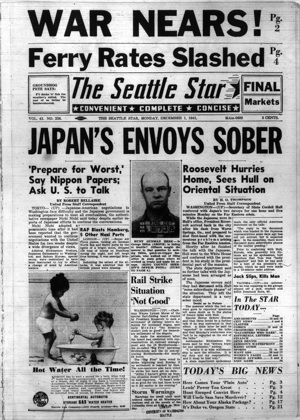

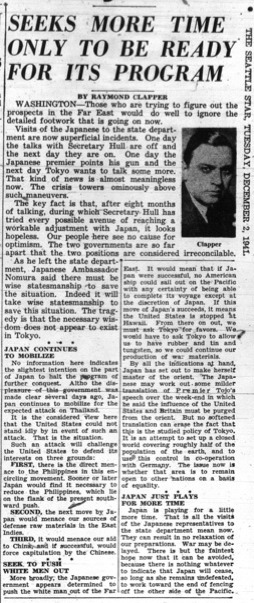

At the beginning of December the Seattle Star focused largely on Admiral Kichisaburo Nomura, Japanese Ambassador to Washington, and Saburo Kurusu, special envoy, who were charged with effecting a change in the minds of American leaders with respect to Japanese militarism. Daily columnist Raymond Clapper felt “Japan’s stalling, plainly that.”6 When Japan rejected the US request that it leave French Indo-China, the Star called Saburo Kurusu a “modern day Judas.”7

On December 8, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the war declaration with Japan after he went before a joint session of both houses and pledged that the US would triumph over treacherous Japan, “so help us God.”8 The Star’s Raymond Clapper, also outraged by Pearl Harbor, was more far more bombastic in his prediction. “Japan has chosen to live by the sword and she will die by the sword,” Clapper wrote. “Japan will be blasted, bombed, burned, and starved. Her people will suffer ghastly tortures. A nation which had possibilities of becoming one of the rulers of the world will be reduced to a pitiful huddling people on a poor little group of islands.9” Clapper’s column, with its vision of “ghastly tortures” and of the Japanese as a “pitiful huddling people,” set the tone for much of the Star’s subsequent war coverage.

The day after the Pearl Harbor attacks, the Star also reported on its front page that Attorney General Francis Biddle announced that Federal Bureau of Investigation agents had “seized” 736 Japanese nationals in the United States and the Hawaiian islands.10 Here the language is significant. The word “seized” seems rather harsh when considering that the vast majority of those detained were innocent, law-abiding people. Yet many at the time felt that this extreme measure was necessary to protect national security.

While this article appeared on the front-page, another article, this one about American-born Japanese pledging loyalty to the US, appeared on the fourth page. The article featured James Sakamoto, a prominent Japanese-American journalist and community leader and his wife. After news of the beating of a Japanese person in Seattle broke, Mrs. Sakamoto is quoted as saying, “I was going to take the children downtown to do some Christmas shopping but I’m afraid it may not be safe.”11 Her husband agreed, saying that he believed there was “a remote possibility of our becoming the victim of public passion and hysteria.” And yet Sakamoto used the opportunity to reassure readers of the loyalty and patriotism of Seattle’s Japanese and Japanese American residents. “If this should occur,” Sakamoto said, “we will stand firm in our resolution that even if America may ‘disown’ us we will never ‘disown’ America.” He later acted as the General Chairmen of the Japanese-American Citizens League where he organized more than 300 volunteers from Seattle’s Japanese community for civilian defense work.12

Sakamoto was the most prominent among a number of Japanese Americans to publicly declare loyalty to this country in the wake of Pearl Harbor. For example, the national headquarters of the Japanese American Citizens League in San Franscio “unequivocally condemned Japan for [the] attack on our country.”13 The Seattle Star had an unbiased view toward Japanese nationals and Japanese-Americans and even added to the article on Sakamoto the “inspiring example” of 3,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry enlisting in the national defense effort, noting that “the percentage in proportion to population is greater than any other racial group such as Italian-Americans and French-Americans.”14 The Star also reported that Japanese-American citizens in Honolulu were praised for their loyalty by both civilian and military officials. Joseph P. Poindexter, governor of the territory of Hawaii, praised them for “the splendid example they are setting for the mainland in calm, determined conduct.”15

Aside from declaring their loyalty, many Japanese citizens rushed to get birth certificates and proper identification16 and turned in guns even though it was not required for non-citizens to turn in weapons.17 To prevent discrimination against them, the Chinese community printed buttons reading “Not from Nippon”18 or wore jackets that said, “Don’t shoot! I’m a Chinaman!”19

Other Seattle Star articles involving Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans included a report of Tacoma police seizing two Japanese loading motion picture films into a car in a “dark alley,”20 an article about special passports being given to Japanese wedding guests stranded in Spokane, and a brief on Hiroshi Mashino, 25, who had just finished a national defense course and was set to work at an airplane plant, but was jailed with five other Japanese.21Although the latter two stories are fairly sympathetic to the Japanese sufferers, the phrase “dark alley” being used to describe the scene in which the Tacoma men where arrested again shows that, like Raymond Clapper’s column, the language used to describe the Japanese played into popular anti-Asian stereotypes.

Although Seattle Mayor Earl Millikin took personal command of the city’s civilian defense groups and ordered 51 Japanese detained. He argued, “Seattle must have tolerance toward American-born Japanese, most of whom are loyal. But I also want to warn the Japanese that they must not congregate or make any utterance that could be used as ground [for] reprisal.”22 Seattle Police Chief Herbert Kimsey, who helped round up Japanese immigrants all through the night, also preached tolerance, declaring that any attempt to stir up anti-Japanese riots would be “crushed with force.”23The Star also chose to quote Rear Admiral C.S. Freeman, commandant of the 13th naval district, who said the “immediate problem for the civilian population is to be on guard for possible sabotage … I realized that the very great majority of our people, including Japanese residents, are loyal to our country and it therefore is important to avoid unjust or unfounded suspicion.”24 This view was also reflected by the Seattle Urban League, which urged citizens not to get involved in any measures and to allow the government agencies to handle the control measures.”25 By presenting these views and favorable comments about the local Japanese population the Star almost seems to be trying to convince individuals that they should be tolerant of others.

A roundup of 122 Japanese, 27 German, and 3 Italian “enemy aliens” was announced Tuesday, December 9th by H. B. Fletcher, special agent in charge of the Seattle FBI office. Fletcher added that possibly more aliens would be picked up in the following weeks.26 The Star reported that nationwide, more than 900 Japanese, more than 300 Germans, and about 40 Italians had been detained. The following day, Wednesday, the number of local Japanese who were arrested stood at 156.27 On Thursday, the national totals were at 1,291 Japanese, 865 Germans, and 147 Italians. By December 20th that number was at 1,460 Japanese, 1,204 Germans, and 222 Italians.28 Attorney General Biddle said that “no sabotage of 5th column activities had been reported to the FBI” and that some of those detained would to be released after hearings while the others would be sent to concentration camps in Fort Missoula, MT, Lincoln, ND, and Stanton, NM… The paper reported that the raids were staged under a proclamation secretly issued by President Roosevelt. Meanwhile, the Justice department sped a campaign to prevent persecution of “peaceful and law-abiding” Japanese, naturalized or alien.29

During this time local citizens’ fears grew, as evidenced by some rather ludicrous claims that were reported by the Seattle Star. One article featured an alderman, H D. Witon, who charged that Japanese wardens at the Boeing Aircraft plant had control of flashlights during blackouts and could signal to attacking aircrafts. Witon’s claim was taken seriously enough to be investigated by ARP officials.30Another article detailed how anyone who had spent the last five out of ten years in Washington State could withdraw a pension regardless of citizenship. The Star seemed to be suggesting with this article that that should not be the case. Another strange story was a letter written by a W.D.M. who said that on December 1st, the Japanese Hotel Association had said “‘for various reasons we are obliged to raise you rent $1 more per month.’ On December 7th, the Japs began war upon the United States. Perhaps it can be investigated.”31W.D.M seemed to be suggesting a conspiracy was afoot between local Japanese American businessmen and the Japanese military.

One thing that comes through in the _Seattle Star_letters-to-the-editor section is the somewhat surprising ability of people to differentiate between Japan and people of Japanese ancestry living in the United States. As one _Star_reader commented, “[t]he Japanese present a popular enemy … we hate the Japs,” and then in the same letter went on to state, “[i]n this country, a good many Japanese have already been taken into internment. I am told Mayor Millikin is taking steps to protect Seattle Japanese. This is a commendable gesture.”32 Sharing this view was K.C.H. who argued that it was not fair to condemn all Japanese residents for what Japan was doing and urged readers to continue to frequent Japanese-owned fruit stands. K.C.H. writes that “[they] came to this land of the free to make an honest living. Their sons and daughters were born here and attend our schools and many of our various churches.”33 Another letter printed December 22nd read,

There are many stories of abuses of and discrimination against Japanese-Americans. Much of it apparently without thought and foundation. Let’s not do that any more. Many of them are Christians and good Americans. Think of yourselves in their position. It’s tough. Japanese-Americans can do much to help themselves by wearing a pin, “I am an American-Christian” and reporting all subversive acts, and those engaged in them. That is the plain duty of every American.

It is striking, though, that both of the selected letters refer to churches or Christians. What of the many loyal Japanese-Americans who were not Christians?

III. January 1942

At the start of the New Year, Japan was advancing into Burma, having already captured Manila, North Borneo, and Rabaul. The British were forced to withdraw into Singapore and a siege of Singapore began January 31st. Still, the United States was confident that it would win the war. The economy at home was finally booming due to the war after more than a decade of depression. And Japanese internment was becoming an accepted idea among many as an answer to the perceived threat of espionage and subversion.

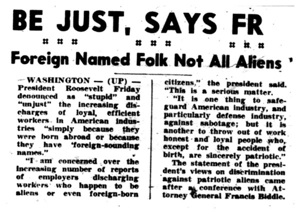

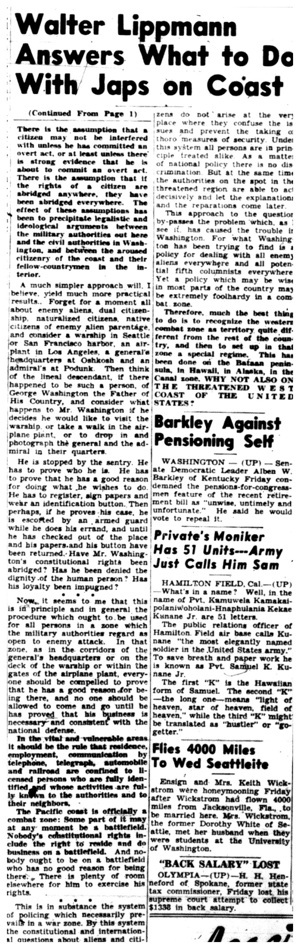

On January 2nd, the Seattle Star reported that President Roosevelt had confessed his concern “over the increasing number of reports of employers discharging workers who happen to be aliens or even foreign-born citizens.”34 Roosevelt, who issued the executive order authorizing Japanese internment, went on to say, “it is one thing to safe-guard American industry and particularly defense industry, against sabotage; but it is another to throw out of work honest and loyal people who, expect for the accident of birth, are sincerely patriotic.”35 Star reader Joseph E. Mackinsly agreed with the president, writing that “[t]he mixing and blending of these peoples thru native born or naturalized citizenship is what makes us Americans … what we need in this country right now is fewer morons in executive positions.”36 Mrs. C. E. Baum shared this view, stating that “[o]ne hears of Japanese school children being forced off buses by schoolmates undoubtedly influenced by ignorant parents … racial persecution has no place in the American way of life, as it is the various contributions of each race which makes the United States the unique nations it is.”37 This sample of the readership and the _Star_’s decision to print them left the impression that the paper was on the side of the Japanese. However, aside from these letters to the editor from concerned citizens, very few news stories documenting the harassment faced by the local Japanese population appeared in the Star. It is as if the Star’s editors believed that such stories were not worth reporting.

Tighter restrictions soon began to be placed on Japanese residents. They were no longer allowed to bear arms and were limited in their travel. Along with these increased restrictions, Attorney General Biddle and President Roosevelt announced requirements for the re-registration of 1,100,000 aliens38 in the United States, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. It was well known that internment for the duration of the war awaited those that failed to comply with the re-registration order.39

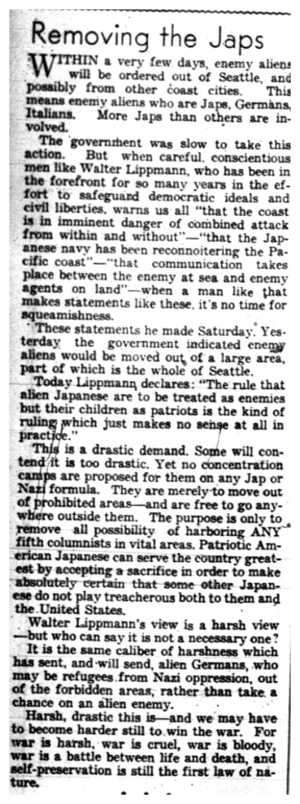

It was also in January that the paper began running articles on the proposed ban of Japanese along the British Columbia coast.40 Alderman H. D. Wilson is reported as having said, “Japanese should be rounded up first and investigated later.” To balance this view the paper also ran Mayor J. Cornett’s warning against any action that might embarrass the Canadian government. Later, the Star wrote that Mayor Cornett also felt that moving the aliens might affect the thousands of American and Canadian nationals in Japanese custody. He suggested that the decision be delayed for two weeks.41 He was unsuccessful and less than a week later the Star reported, “Canada clears coast of Japs.”42Here it seems that local and national sentiment was for the removal of Japanese from coastal regions along the Pacific coast yet the paper still does not yet overtly call for such measures. Nevertheless, the Star did publish several reports showing life in Japanese interment camps as pleasurable. For example, the January 12th issue reported that “Alaska Japs treated well,” adding that the life they were said to lead was “peaceful” and the treatment they are receiving is “generous.”43

Also reported was an incident in which three American citizens and three Japanese nationals were indicted by a federal grand jury in connection with the illegal distribution of pro-Japanese propaganda.44 A follow-up article on four Japanese accused of conspiring to export military equipment and munitions to Japan was also printed. Although the headline of the later article ran “4 Japanese accused of conspiracy,” it concluded by saying that a Russian, an Englishman, and Japanese who failed to comply with the alien registration act were also indicted. In other words, although the conspiracy allegedly involved people from several nations, the Japanese were singled out in the headline.

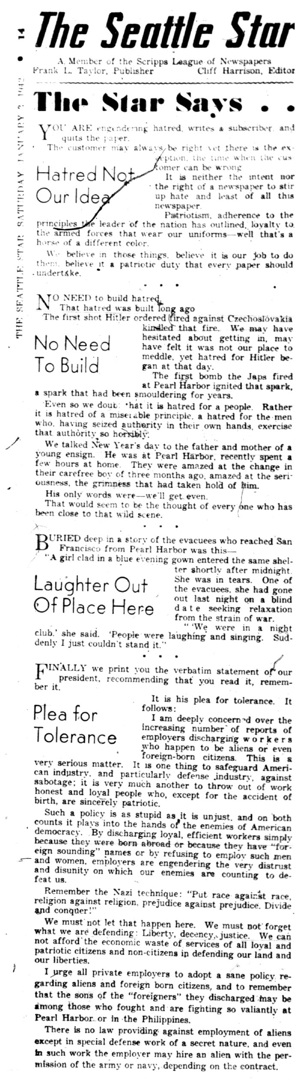

On January 14th the Seattle Star announced it had been sold to Howard Parish and Associates. The policy of the paper, Parish stated, “will be directed by Abe Hurwitz and myself.”45 The ownership change had a dramatic impact on the newspaper’s coverage of Japanese Americans and the war. After the sale strikingly different “Star Readers Say” articles were printed and revealing new sections were added to the paper such as “Japan Unmasked” by Hallet Abend. Gone were the mostly temperate letters and articles calling for tolerance. In their place, the Star became more aggressively anti-Japanese and made fewer distinctions between the Japanese government and military and people of Japanese descent living in the United States. An example of the new type of letters to the editors is showcased in Virginia Scott’s comment:

Let us to be able to say ‘We did it,’ instead of ‘We should have done it’! Let’s move the West Coast Japs inland before they move us! (that would be a good slogan) Canada decided on this move, and Russia used this plan to help her defeat fifth columnist activities on her borders. It would be a big job, no doubt and would be very expensive, but we have such a beautiful country, and so many precious lives at stake – we just can’t afford to over look any bets.

Another letter to the editor, this one by a Ruby L. Salmon, shared this sentiment, arguing that “all foreign born American-citizens … [and] school-children should be asked to speak American … on the streets. When in America do as the Americans.”46 Contrast this with the earlier letters, quoted above, praising the contribution of Japanese residents to America’s celebrated diversity.

III. February 1942

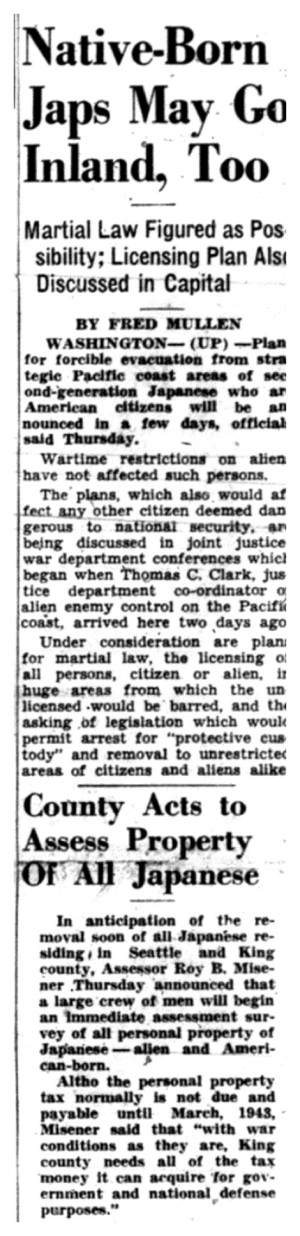

On February 19th, 1942 President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which allowed Japanese nationals and U.S. citizens of Japanese descent to be sent to internment camps for the duration of the war. According to the Star, Seattleites agreed with the order. “Seattle individuals and groups are continuing to urge mass removal of all Japanese, whether aliens or American-born,” the paper reported.47“Seattle sentiment in favor of the removal… rose to a high pitch here.”48 Seattle American Legion posts Magnolia No. 123 and Walter Akeley No. 29 were among a number of local groups that announced adoption of a Bellingham American Legion resolution asking for immediate expulsion of all Japanese and other enemy aliens from the Pacific Coast for the duration of the war, and the Kiwanis agreed.49 Later, American Legion posts in Spokane, Elma, Yakima, Seattle, Wenatchee, Wapato, Naches, Toppenish, Richland, and Seattle University voiced their support for the removal of Japanese residents.50

There were a few dissenters though, and the persons and organizations friendly towards American-born Japanese and alien Japanese made every effort to save them from undue hardships. One such group was the American Friends Service Committee. The AFSC’s Seattle representative, Floyd Schmore, issue a statement that “The state, county, and city church councils are among those who by telegrams and letters to the department of justice are seeking to save [the Japanese] from evacuation.” Floyd M. Oles, manger of the Washington Produce Shipper’s Association, appeared before a government committee and highlighted the monetary losses that would be felt if Japanese and Italian labor was forced to leave. James Sakamoto also appeared before the committee as a witness. However, by February 16th, it was decided that all Japanese were to leave Seattle without exception. Seattle had been designated a “Class A” enemy alien prohibition zone. Japanese residents were given two weeks to report to the interment camps.51

Raids were still being carried out. The _Seattle Star_reported a Bainbridge Island raid involving fifteen Japanese who were jailed at an immigration station after being found with firearms and weapons.52 As a large-scale exodus of Japanese began in California and all along the West Coast, it was debated if martial law could be used to speed up the process and force reluctant Japanese to leave.53 District Director of the US Immigration and Naturalization Service Raphael P. Bonham stated that “quasi-martial law clauses makes it possible to order [American-born Japanese] to leave the prohibited areas along with those whose citizenship status is definitely defined.”54 On February 24th the _Seattle Star_finally ran the total number Japanese sent to internment camps – it was near 2,000 in Fort Missoula and Bismarck, North Dakota.55 The paper also reported that Japanese aliens who were evacuated could work at the 20,000 jobs offered at sugar refineries in Idaho and California.56

Japanese citizens’ rights become more restricted as Governor Arthur B. Langlie’s order included provisions for the Seattle FBI to seize firearms from any Japanese citizen.57Furthermore, the prohibited areas from which Japanese were barred were extended58 and included City Light’s Skagit project, Grand Coulee and Bonneville dams, and the Long Lake hydroelectric plant.59

As the Japanese awaited evacuation, they were photographed, fingerprinted, and interviewed by both immigration authorities and the FBI and often subjected to harsh treatment and excessive regulation.60 Designated re-registered aliens, Japanese were required to carry different certificates of identification and carry three photographs of themselves two by two inches in size, taken within thirty days since the date of application, on a light background.61

One striking story reported by the Star was that of a group of Gatewood mothers who sought to dismiss the female Japanese clerks who worked in the school district. The mothers, members of the Parent Teacher Association (PTA) collected signatures to petition the school board. Mrs. Dale J. Marble, President of the Seattle PTA council confirmed that the council representatives had twice protested the employment of Japanese girls.62 The twenty-six girls finally resigned, declaring in their blanket resignation, “we take this step to prove our loyalty to the school and to the United States by not becoming a contributing factor to dissention and disunity when national unity in spirit and deed is vitally necessary to the defense of and complete victory for America.” The Seattle Star deserves credit for posting the girls’ opinion and the reasons why they resigned.

As for letters to the editor, they appeared very similar to the ones that ran in January. For example, W.L. of Seattle writes,

[I]n regards to the removal of all Japanese and their allies on the Pacific coast, if we don’t [move them], they are liable to move all of us.

My wife and I have raised a family of boys and girls here in the northwest who are now raising their own families and buying their own homes. All the boys are of draft age, registered and ready to go and fight to preserve the freedom of our country and what it stands for.

As a citizen and taxpayer who has a stake in these United States, I believe it would be best for the welfare of our people that all enemy aliens be removed to a place inland where they could do no harm.

Fear of offending has cost our country plenty especially in regard to Japan. We are inveterate appeasers, and sentimental and the Japanese and their allies have not the word sentimentality in their vocabulary. Germany proclaimed the death penalty for anyone helping an American or their allies.

When we put our enemies in a safe spot inland we will be safe from within. Don’t let us be sentimental fools all our lives, remember what the Japs did to our 30,000 Americans in the Far East so they lost all business and families ties. Also what they did when they conquered Manchuria in 1932. For heaven’s sake don’t let that happen here.

V. Conclusion

Although the Seattle Star is just one newspaper, and Seattle is just one city, this analysis of the Star’s coverage of the Pacific War and the issue of Japanese interment offers an interesting vantage point from which to view of evolution of both the newspaper’s and the general public’s views of Japanese Americans over the first two months after Pearl Harbor. The letters to the editor give perhaps the clearest indication of this evolution, which corresponded with the change in ownership of the Seattle Star in January 1942. Overall, the letters went from asking for tolerance towards Japanese residents to calling outright for internment camps and expressing increasing alarm about the threat of Japanese people in the United States. It was this fear, a fear that was directed toward Japanese people in ways that it was not directed toward either German-Americans or Italian-Americans, that led Seattle officials to abridge the rights of Japanese immigrants and Japanese-American citizens and, on a national level, led to Roosevelt’s executive order authorizing wartime internment camps.

Copyright © Rochelle Krona 2008

HSTAA 498 Winter 2007

1 Kenneth B. Pyle The Making of Modern Japan (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996), 183

2 Pyle, The Making of Modern Japan, 184

3 John. W. Dower, War without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (New York: Pantheon, 1986), 205

4 “Seven jailed, 20 stores hit,” The Seattle Star, December 9, 1941, pg. 4

5 The Seattle Star, December 8th, 1941, pg. 10

6 Raymond Clapper, The Seattle Star, December 2, 1941, pg 3

7 “Saburo Kurusu Modern Day Judas,” The Seattle Star, December 8, 1941, pg. 17

8 “Speed Action by Congress,” The Seattle Star, December 8, 1941, pg. 1

9 Raymond Clapper, “America can be proud we tried to avoid war,” The Seattle Star, December 8, 1941, pg. 3

10 “736 Japan Nationals held in custody,” The Seattle Star, December 8, 1941, pg. 1

11 “’We are loyal to the US’ – pledge of American-born Japanese voiced by blind Seattle publisher,” The Seattle Star, December 8, 1941, pg. 4

12 “Japanese to Aid Defense,” The Seattle Star, December 18, 1941, pg. 28

13 “’We are loyal to the US’ – pledge of American-born Japanese voiced by blind Seattle publisher,” The Seattle Star, December 8, 1941, pg. 4

14 “’We are loyal to the US’ – pledge of American-born Japanese voiced by blind Seattle publisher,” The Seattle Star, December 8, 1941, pg. 4

15 “Attacking Japs knew Honolulu’s strategic points. Loyalty praised,” The Seattle Star, December 12, 1941, pg. 3

16 “War comes to Seattle,” The Seattle Star, December 10, 1941, pg. 10

17 “300 Guns turned in by Axis Aliens,” The Seattle Star, December 31, 1941, pg. 6

18 “Not from Nippon,” The Seattle Star, December 13, 1941, pg. 5

19 “Chinese boy tell ‘em he’s not a Jap,” The Seattle Star, December 17, 1941, pg. 6

20 “USA and war – how the nation reacted,” The Seattle Star, December 8, 1941, pg. 4

21 “Special passports,” The Seattle Star, December 8, 1941, pg. 4

22 “Seattle assumes wartime pace; 51 Japs held,” The Seattle Star, December 8, 1941, pg. 6

23 “Seattle assumes wartime pace; 51 Japs held,” The Seattle Star, December 8, 1941, pg. 6

24 “Seattle assumes wartime pace; 51 Japs held,” The Seattle Star, December 8, 1941, pg. 6

25 “Ask Tolerance,” The Seattle Star, December 11, 1941, pg. 7

26 “400 axis, 900 Japs rounded up by FBI,” The Seattle Star, December 9, 1941, pg. 5

27 “FBI arrests 156,” The Seattle Star, December 10, 1941, pg. 10

28 “Name ‘Enemy Alien’ Boards,” The Seattle Star, December 20, 1941, pg. 3

29 ‘FBI agents seized nearly 400 German and Italian aliens in nationwide raids Monday night,” The Seattle Star, December 8, 1941, pg. 5

30 “ARP Officials investing a charge…” The Seattle Star, December 12, 1941, pg. 28

31 “To be investigated,” The Seattle Star, December 30, 1941, pg. 31

32 “Star Readers Say,” The Seattle Star, December 8, 1941, pg. 10

33 “Star Readers Say,” The Seattle Star, December 12, 1941, pg. 14

34 January 2nd, pg. 3 “Be just says FR”

35 ibid

36 January 7th, pg. 7 “What’s in a Name” in Star Readers Say by Joseph E. Mackinsly

37 January 10th, pg. 14 “More tolerance” in Star Readers Say by Mrs. C. E. Baum

38 “Reregister Aliens,” The Seattle Star, January 7, 1942, pg. 21

39 “Axis Aliens to register in Seattle,” The Seattle Star, January 31, 1942, pg. 1

40 “Ask Ban on Japs along B.C. coast,” The Seattle Star, January 5, 1942, pg. 6

41 “Urge delay on law affecting Japanese,” The Seattle Star, January 8, 1942, pg. 12

42 “Canada clears coast of Japs,” The Seattle Star, January 14, 1942, pg. 1

43 “Alaska Japs treated well,” The Seattle Star, January 12, 1942, pg. 5

44 “3 Americans, 3 Japs Indicted,” The Seattle Star, January 28, 1942, pg. 2

45 “Star Sold: Howard Parish and Associates purchase Seattle Newspaper,” The Seattle Star, January 14, 1942, pg. 1

46 “Star Readers Say,” The Seattle Star, January 19, 1942, pg. 4

47 “Will study Jap removal issue here,” The Seattle Star, February 23, 1942, pg. 8

48 “Japs face still more restrictions,” The Seattle Star, February 26, 1942, pg. 3

49 “Japs face still more restrictions,” The Seattle Star, February 26, 1942, pg. 3

50 February 20th, pg. 5 “Move for Evacuation”; February 17th, pg. 5 “Legion Post for Japanese ouster”

51 February 16th, pg. 1 “Coast to be closed by army”

52 February 5th, pg. 1 “Bainbridge Japs Jailed, Gun seized”

53 February 9th, pg. 1 “Alien Exodus in South”

54 “Wait word on removal of aliens,” The Seattle Star, February 17, 1942, pg. 12

55 “12 more Seattle Japanese sent to Interment Camps,” The Seattle Star, February 24, 1942, pg. 1

56 “Jap Aliens get tentative offer of 20,000 jobs,” The Seattle Star, February 24, 1942, pg. 5

57 “State to disarm all Japs,” The Seattle Star, February 21, 1942, pg. 1

58 “Japs face still more restrictions,” The Seattle Star, February 26, 1942, pg. 3

59 “Bainbridge Japs Jailed, Guns seized,” The Seattle Star, February 15, 1942, pg. 1

60 “Quiz Japanese-Americans as evacuation awaited,” The Seattle Star, February 23, 1942, pg. 4

61 “Axis Aliens Register,” The Seattle Star, February 2, 1942, pg. 4

62 “Japanese clerks in school hit,” The Seattle Star, February 24, 1942, pg. 5