As the summer of 1891 drew to a close, John N. Conna walked into the New York Kitchen in downtown Tacoma—an establishment he knew would not serve him—and politely ordered supper. Conna’s assumption was correct. The waiter refused to serve him. The owner of the New York Kitchen, L.C. Riggs had instructed his staff not to serve any “colored” people. Within a few weeks, Conna filed criminal action against Riggs in Justice Arnston’s court, arguing “on account of his race, Riggs had refused to furnish him eating accommodation.”[1] Conna’s case was a test.

The year prior, Conna—who, because of his political influence in Tacoma, had served as Assistant Sergeant-at-Arms during the 1889 and 1890 Washington State Senate sessions—helped campaign for, write, and lobby the Public Accommodations Act.[2] The act entitled all citizens, regardless of race, color, or nationality, to equal enjoyment of “public accommodations, advantages, facilities and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters and other places of public amusement, and restaurants.”[3] When the law went into effect upon the ratification of the Washington State Constitution in 1890, Conna wanted to see if it worked—and it did. The case was prosecuted, and Conna won.

The Connas were one of the first Black families to arrive in Tacoma. John Conna was born enslaved in San Augustine, Texas in 1843. At twenty, Conna escaped to New Orleans, enlisted in the Union Army, and fought in several battles in an all-Black regiment. After the war, he moved to Hartford, Connecticut and then to Kansas City before moving west to Tacoma in 1883 when the continental railroad reached the city. Conna used his Civil War benefits to purchase his family a 160-acre homestead in what was then North Tacoma.

By the time Washington gained statehood in 1889, Conna had established himself as an integral figure in the state. He placed advertisements in East Coast newspapers to recruit Black laborers to move west to Tacoma, led the Black voting bloc in the city, served as the first president of both the John Brown Republican Club and the Washington State Protective League and a he was a member of the NAACP’s predecessor, the Afro-American League.[4] Six years after his family moved to The City of Destiny, on Christmas Eve, 1889, John Conna and his wife Mary left the city they loved a gift: The Conna Addition—40 acres of land on what is now the 5400 block of 41st Avenue North, donated and dedicated for “public use forever.”[5]

John N. Conna’s victory in Conna v. Riggs seemed to signal progress—a case proving Washington’s newly ratified Public Accommodations Act could protect residents of color from racial discrimination. But the success of one man’s legal battle did not guarantee equality. As Tacoma grew, racial prejudice took on new, more insidious forms. Over the following decades, segregation would become embedded not just in public accommodations but in the geography of the city itself—enforced by real estate practices, restrictive covenants, and racialized federal housing policies shaped Pierce County’s neighborhoods.

A City Founded on Exclusion

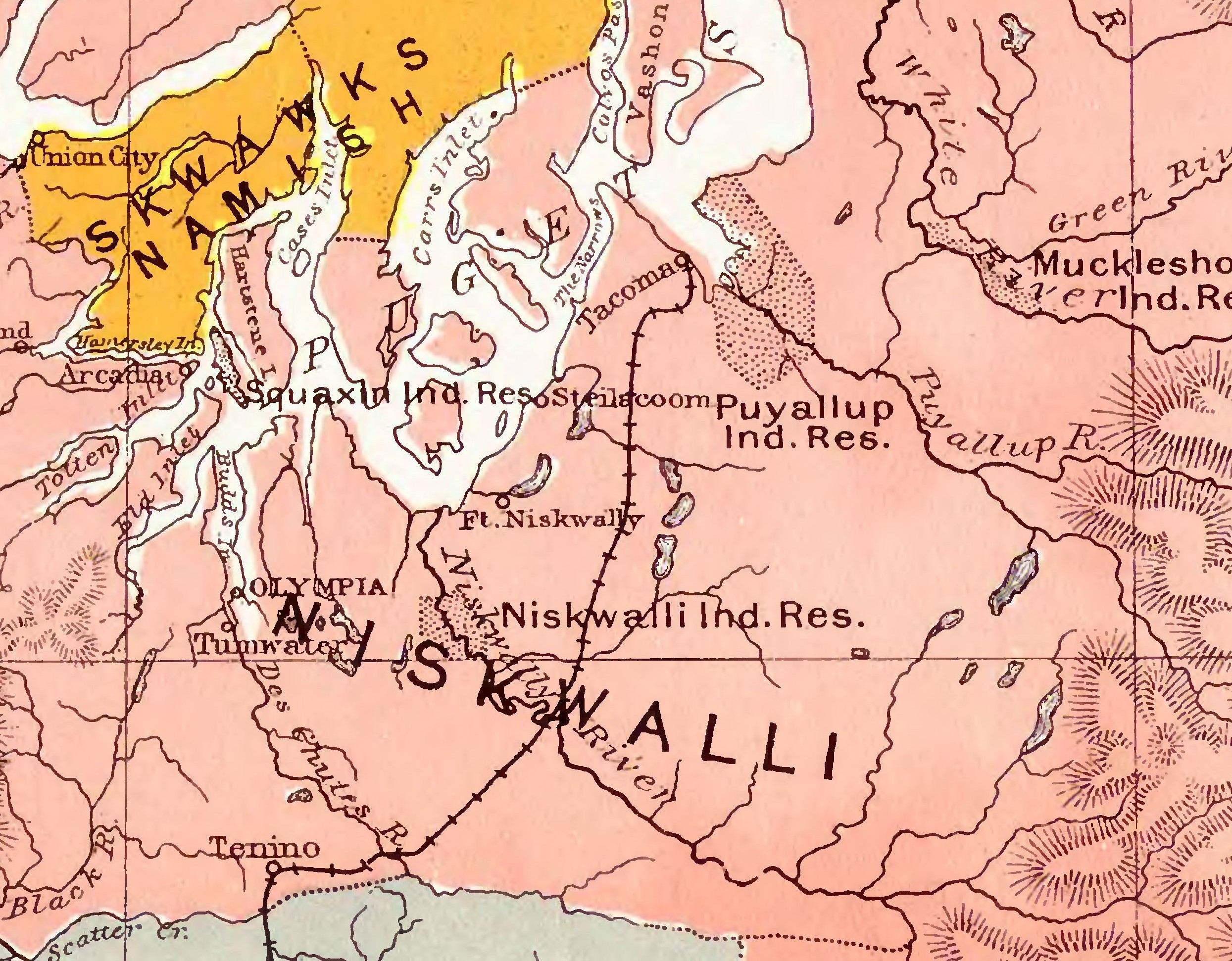

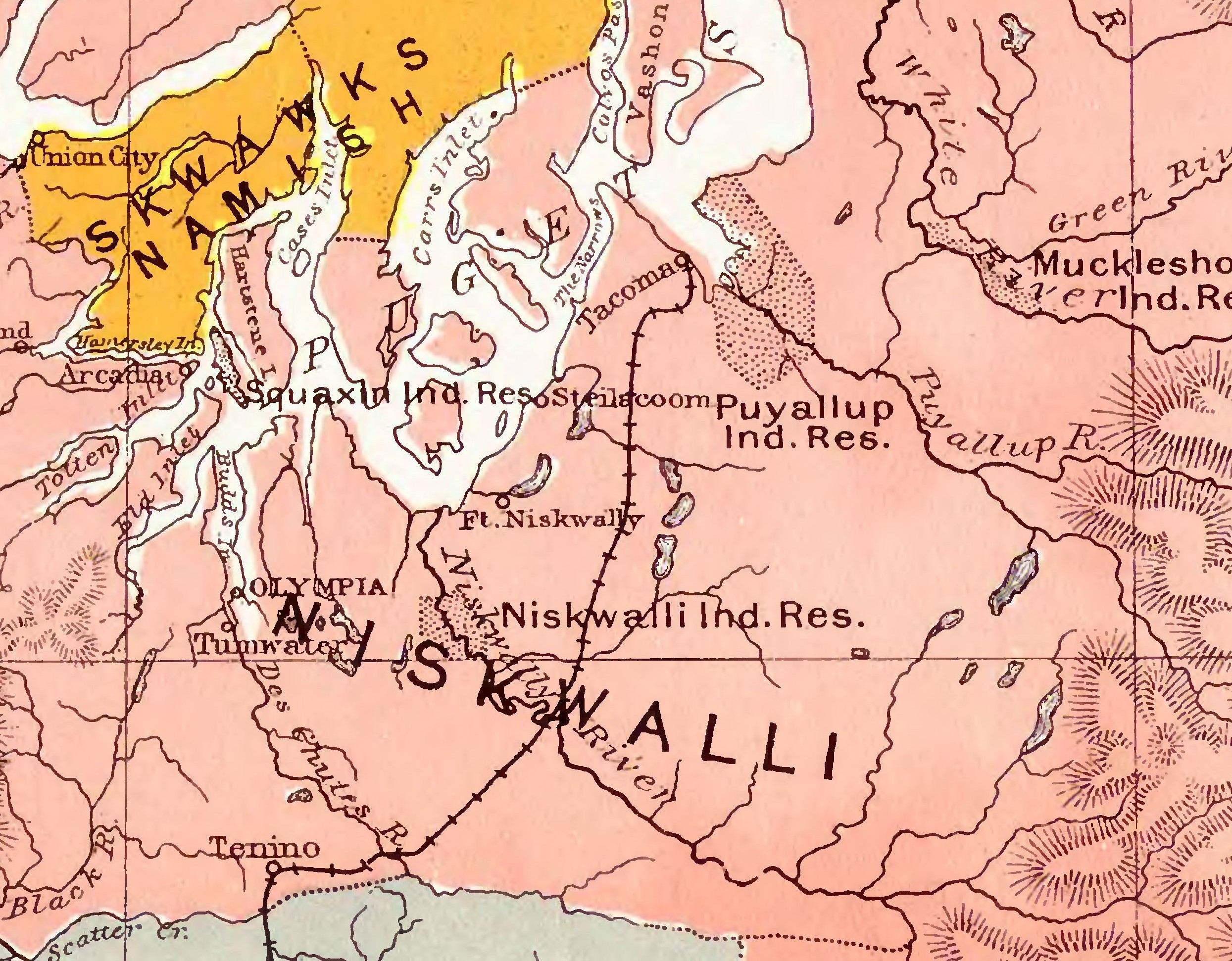

selection from 1876 map by Department of the Interior shows tribal reservations and original tribal territories. Notice the area designated for the Puyallup reservation which includes much of present-day Tacoma and Fife. Despite the treaty, these lands would later be seized.

selection from 1876 map by Department of the Interior shows tribal reservations and original tribal territories. Notice the area designated for the Puyallup reservation which includes much of present-day Tacoma and Fife. Despite the treaty, these lands would later be seized.

When John Conna and his family moved to Tacoma in 1883, they arrived in a city that was only a decade old but built on land from which the Puyallup Tribe had been systematically displaced thirty years prior. Tacoma was founded on the traditional land of the Puyallup Tribe–whose name means "people from the bend at the bottom of the river" and who maintained several villages spanning outward from the mouth of the Puyallup River.[6] The Puyallup Tribe and all of the other tribes around Puget Sound including the Nisqually, Puyallup, Steilacoom, Squaxin were systematically displaced from their traditional lands by settlers.

In 1850, the Donation Land Law encouraged settlement in the area by offering land to early settlers. Congress allowed Americans who had occupied and cultivated land for four years before the law’s enactment to claim 320 acres of land and their wives were able to do the same, one square mile in total. Settlers who came after the five years after enactment could claim half that amount. However, titles could not be secured until treaties removed Indigenous claims to the territory.[7] Territorial governor and Superintendent of Indian affairs, Isaac Stevens, aggressively pursued treaties that would cede nearly all Indigenous lands to the Federal government.[8] On December 26, 1854, sixty two leaders of Western Washington tribes gathered at Medicine Creek with Governor Isaac Stevens to sign the Treaty of Medicine Creek. The treaty transferred 2.24 million acres of land to the United States government and confined the Puyallup tribe and other tribes to small reservations, severing their connection to ancestral lands.[9]

The displacement of Indigenous peoples through the Medicine Creek Treaty created the conditions for settlers like John Conna to claim land in Tacoma. This process of settlement accelerated dramatically after July 1873, when the Northern Pacific Railroad Board selected the area as its western terminus.[10] Newcomers flocked to the burgeoning city from all over the country – between 1880 and 1890, Tacoma’s population exploded from 1,098 to 36,006 residents.[11] Some of the new residents were Chinese laborers who came to work on the railroad. Between 1873 and 1885, the Chinese population grew from 250 to 532.[12] Tacoma’s growth was quickly permeated by racial violence and exclusion. In 1882, following the completion of the railroad, the United States Congress enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act, which suspended the immigration of Chinese laborers. This was the first significant law restricting immigration based on race and set a precedent for future exclusionary policies.[13] Anti-Chinese sentiment in the city was growing just as quickly as the city itself.

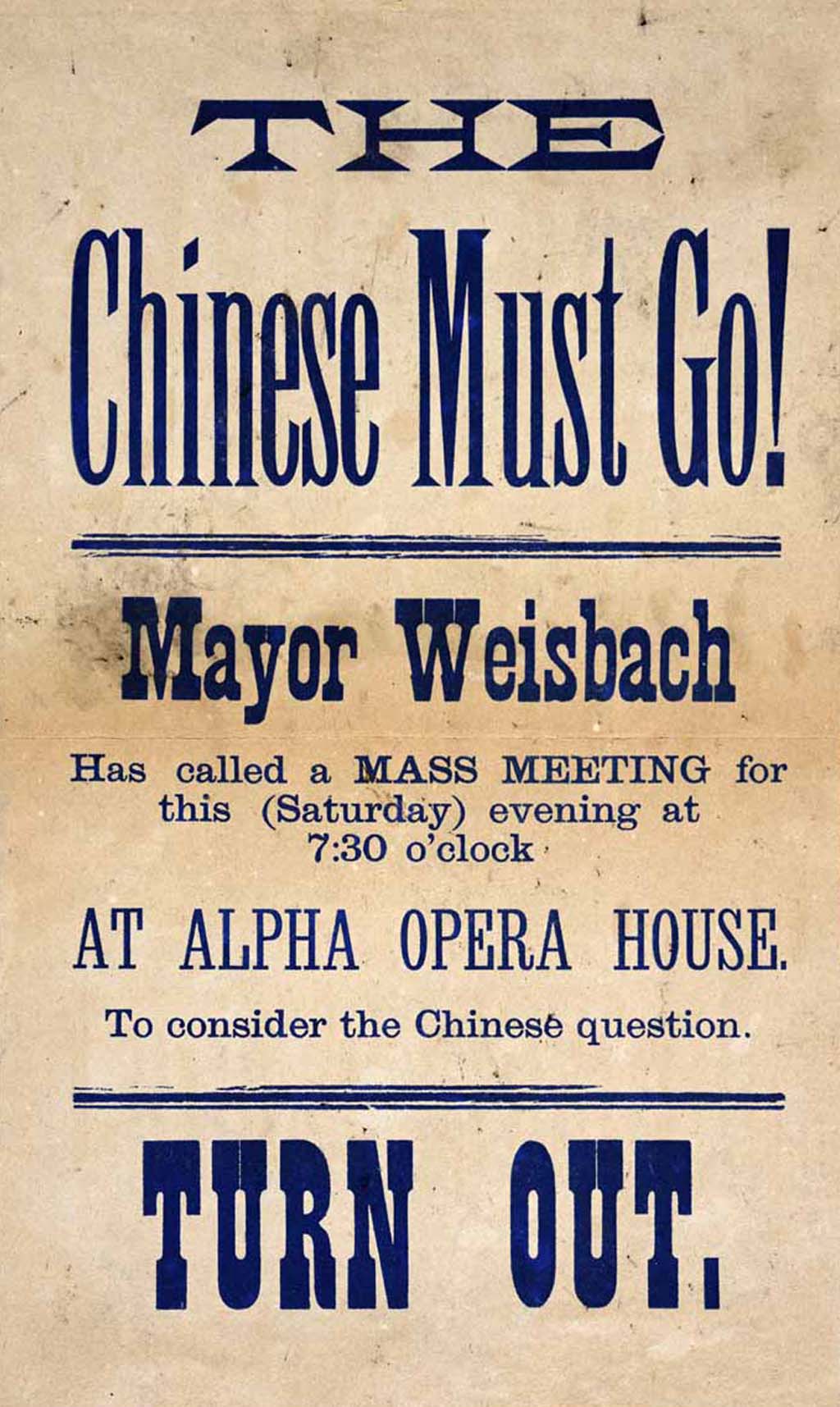

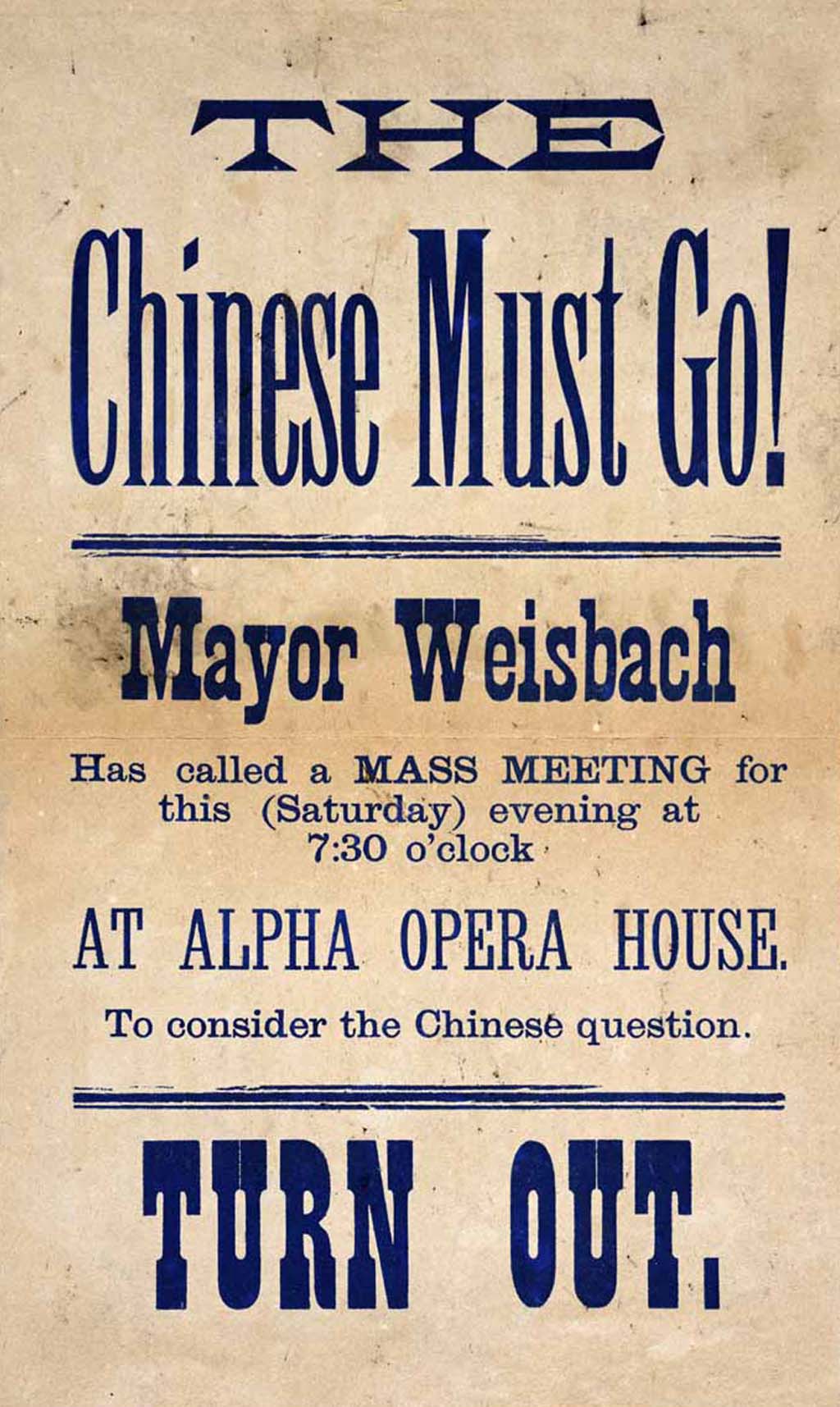

Mayor Jacob Weisbach led the "driving out" actions in Tacoma that destroyed the Chinese settlement.

Mayor Jacob Weisbach led the "driving out" actions in Tacoma that destroyed the Chinese settlement.

In early 1885, the Tacoma City Council attempted to drive out Chinese laborers through legislative means, passing an ordinance requiring 500 cubic feet of air space per person in boarding houses, a measure which purposely targeted Chinese laborers who mostly lived in crowded rooming houses.[14] When Mayor Jacob Weisbach personally inspected the Chinese residences, he declared them out of compliance. The air space ordinance functioned as a thinly veiled strategy to force Chinese people out under the guise of public health.

Anti-Chinese sentiment continued to grow in the following months, organized by a group of white men known as the Committee of Fifteen. The committee set a deadline of November 1st.[15] Many Chinese laborers left before they could be forced out. On November 3, 1885, a mob of 500 white men led by Mayor Weisbach marched through Tacoma’s streets.[16] Every Chinese person in the city was forced onto wagons and trains and removed from the city. Their homes were looted, burned, and destroyed. City officials had not only allowed the expulsion —they promoted it.

In the 1890s, following the horrific expulsion of Chinese laborers, Japanese people began to settle on the west coast, including Tacoma. Most of these early immigrants worked on the railroads, the lumber industry, or in canneries and agriculture.[17] As Japanese immigrants arrived, they were greeted with the same kind of enmity that Chinese people had faced. But the nativists were starting to use new tools, blocking access to property and housing. On March 20, 1907, Seattle-based real estate developer Clarence Dayton (C.D.) Hillman imposed the first known racial restrictive covenant in Pierce County; indeed, the earliest that this project has found in Washington State. Hillman had recently begun plating the City of Pacific, located on the border of King and Pierce counties. Each deed of sale included this restriction intended to be binding on current and future owners: “This contract is transferable to anybody but a colored man, a Japanese or a Chinaman.”[18] Hillman, one of the most prolific developers in the Puget Sound region, would later serve a prison sentence for mail fraud in connection with land sales in Snohomish County.

Racial Restrictive Covenants

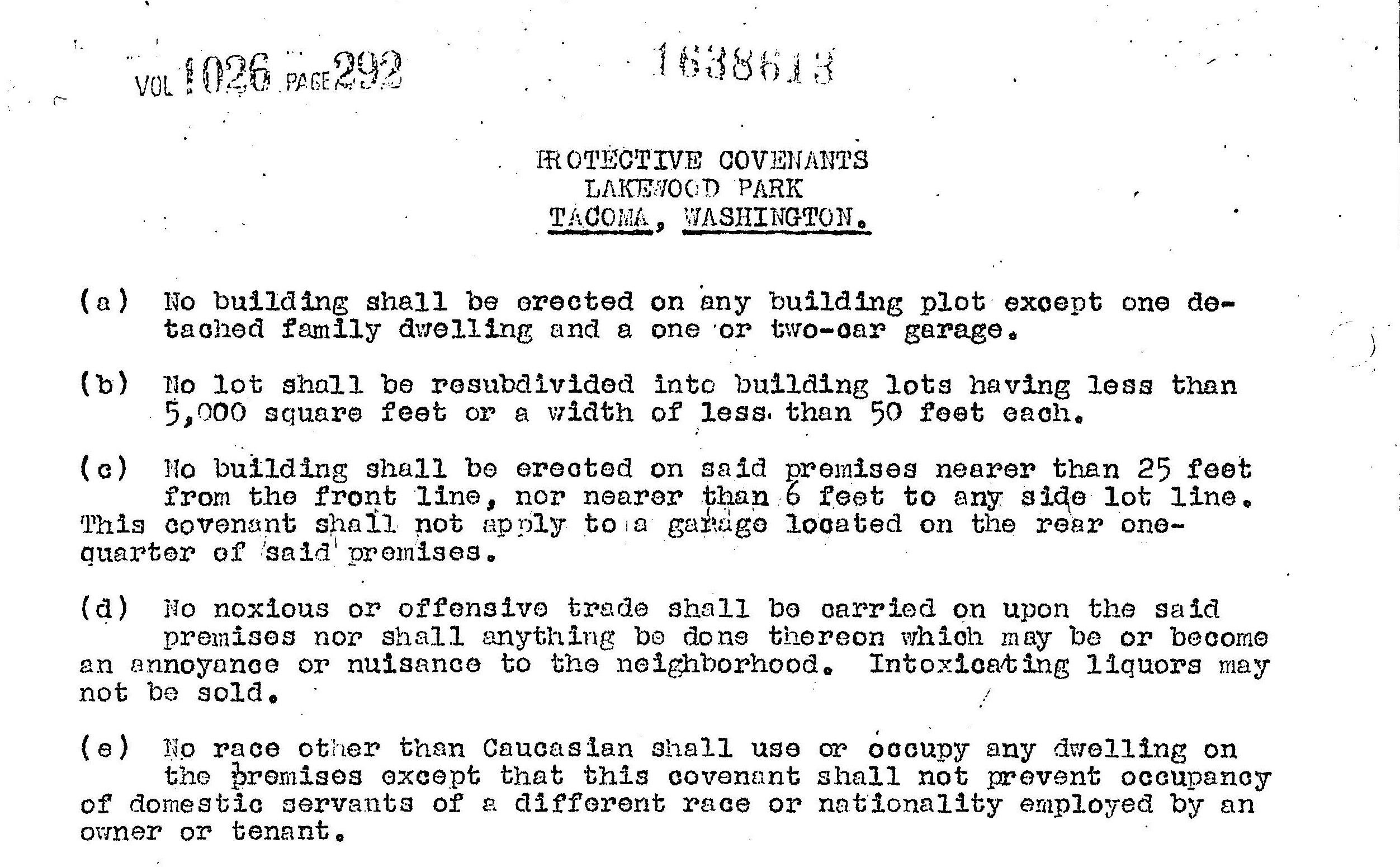

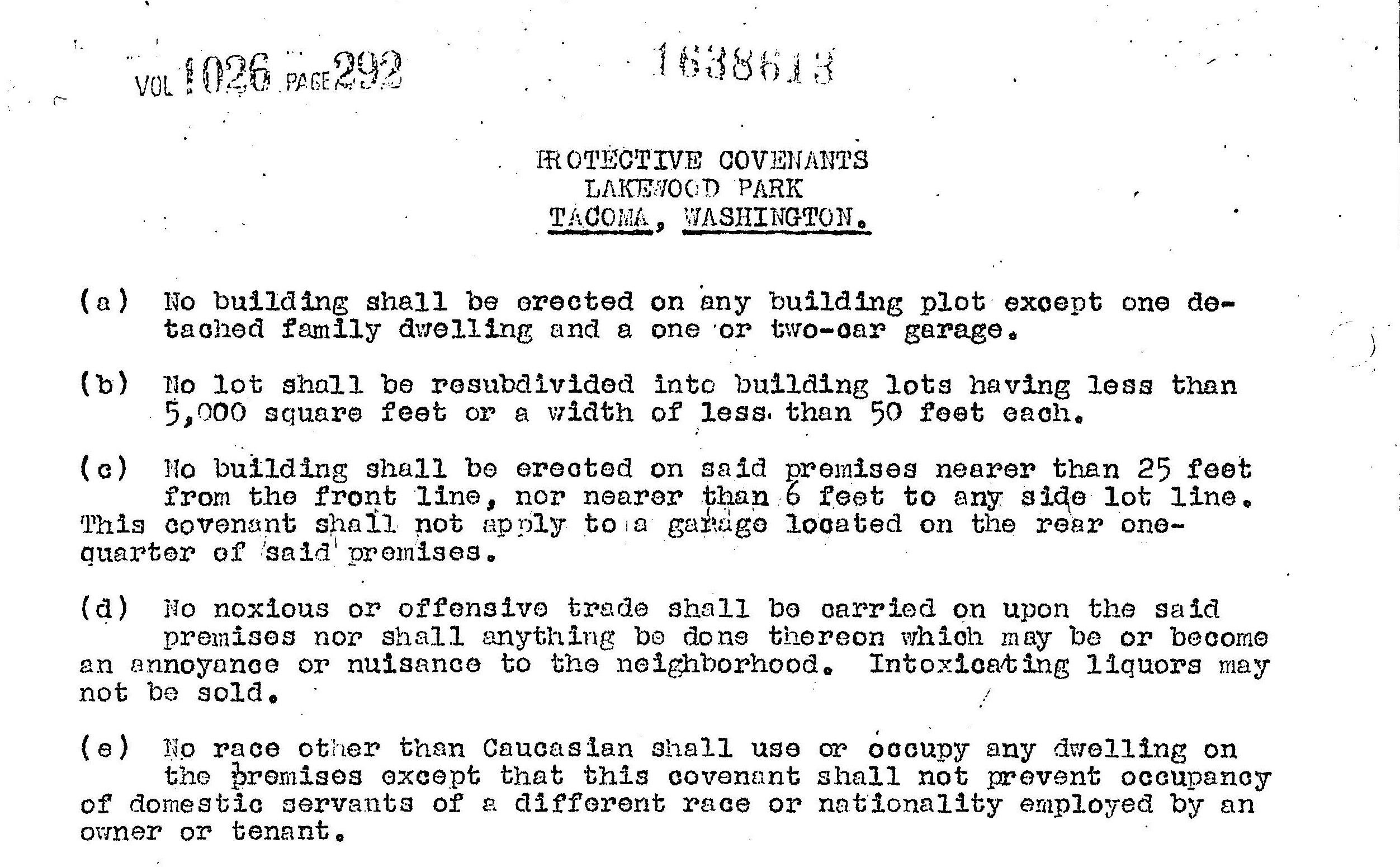

an example of a set of restrictions. Click to see the full document

an example of a set of restrictions. Click to see the full document

Restrictive covenants were recorded by developers and property owners to legally bind future owners not to sell, lease, or allow properties to be occupied by specified racial or religious groups. While Hillman and others began to use them in the first decades of the century, their legal status remained uncertain until the Supreme Court ruled in the 1926 Corrigan v. Buckley case that courts should enforce them as valid contracts. That meant that an owner who rented or sold to a person of color could be sued by neighbors and forced to reverse the sale and potentially pay damages.

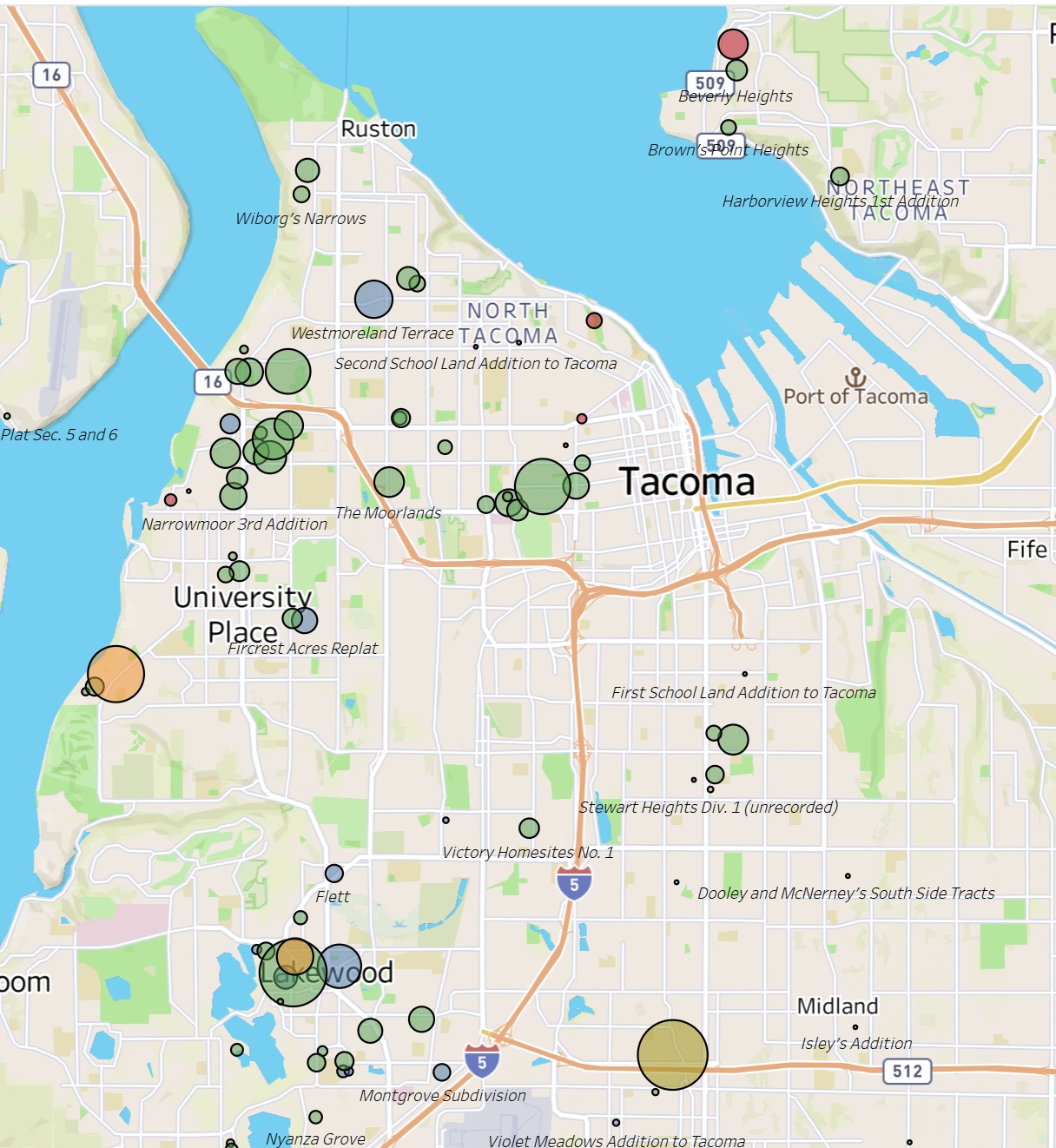

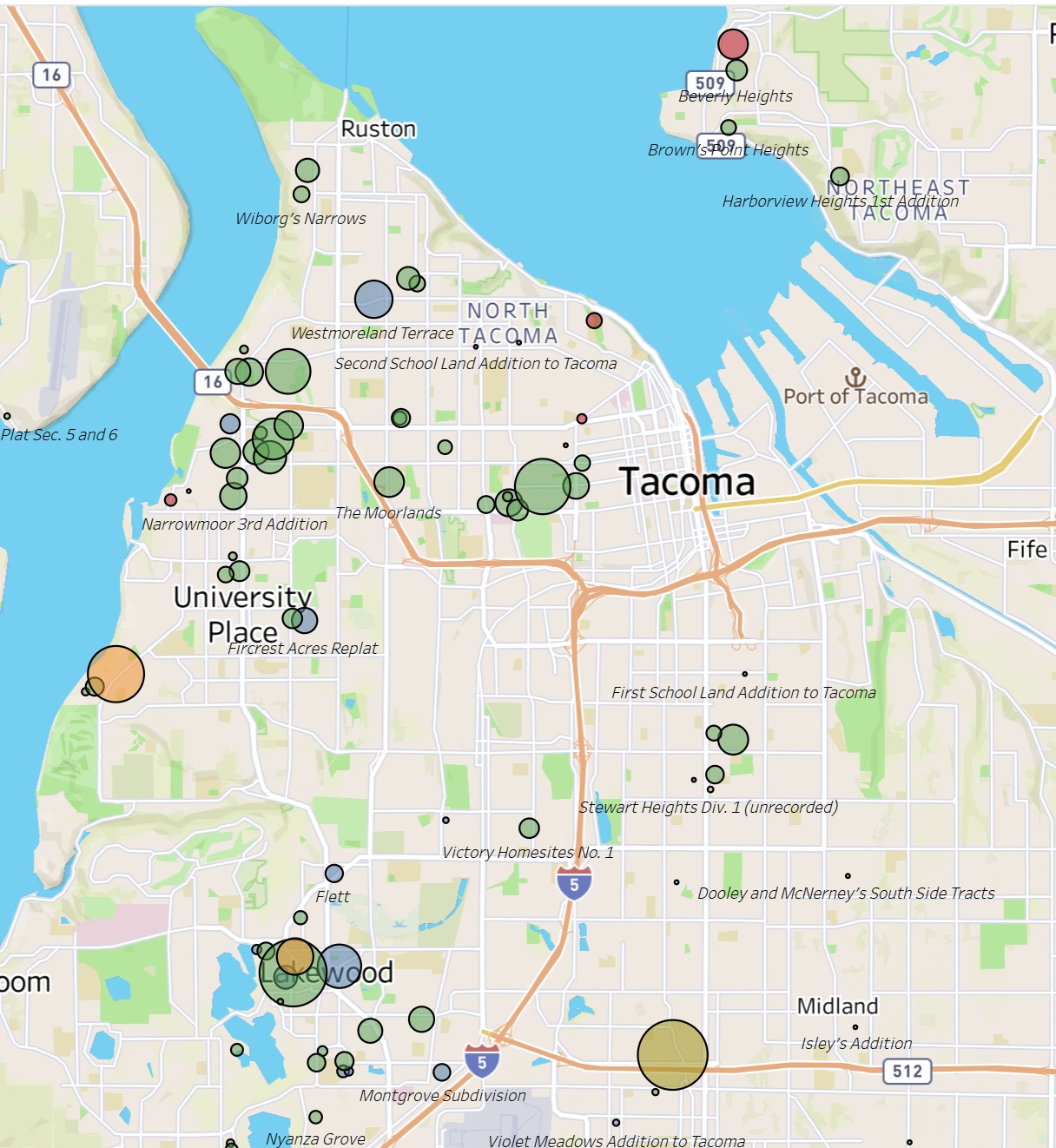

After 1926, the real estate industry promoted the use of restrictive covenants in cities and towns across the country. In Pierce County, a substantial percentage of new subdivisions introduced between 1926 and 1948 would carry racial restrictions, and the practice continued through the 1950s and into the early 1960s. This project has identified more than 6,000 restricted properties in 87 subdivisions in Pierce County.[19]

Click to see documents and our interactive map of subdivisions restricted in Pierce County.

Click to see documents and our interactive map of subdivisions restricted in Pierce County.

The effort to segregate Tacoma was spearheaded by the Tacoma Real Estate Board (TREB). For decades, TREB actively promoted racial segregation in Tacoma and Pierce County. As affiliates of the National Association of Realtors, the Tacoma Real Estate Board adhered to the National code of ethics. In 1924, the National Association of Realtors adopted a by-law clause that explicitly forbade members from selling properties to a person whose presence would be detrimental to the property values of the neighborhood––”A Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in the neighborhood.”[20] This clause provided an economic rationale for racial discrimination which framed segregation as a matter of protecting private property while enabling real estate agents in Tacoma and across the country to use the code of ethics as a tool to enforce racial segregation.

Ward Smith served as president of the Tacoma Board of Realtors as well as many other influential positions. His company routinely imposed racist restrictions in deeds while refusing to show properties to families of color. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

Ward Smith served as president of the Tacoma Board of Realtors as well as many other influential positions. His company routinely imposed racist restrictions in deeds while refusing to show properties to families of color. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

Officers of the Tacoma Real Estate board praised the importance of racist restrictions to enhance sales and preserve property values. Most of the Board presidents were active restrictors themselves, including HA Briggs, who developed numerous subdivisions under several company names and sometimes in connection with the Puget Sound National Bank. Frank Gillette, Ward Smith, and James March were other TREB leaders who developed numerous subdivisions in Tacoma and in the Lakewood area in the 1940s. Another busy restrictor, Louis Muscek, was active in the Real Estate Board while also serving in the City Planning Department.

Indeed, a quick look at the names of developers in our maps reveals a Who’s Who of important figures in the interlocking networks of real estate, banking and savings and loans, and the Chamber of Commerce. This amplifies a critical observation about the role of racial restrictive covenants. They represented governmental forms of racial discrimination, authorized by county recording agencies, enforced by courts, and promoted by the real estate and business elite of Tacoma.

But it is important to understand that covenants were not the principal mechanism of exclusion and segregation. It was difficult to impose deed restrictions on already developed neighborhoods, so properties in neighborhoods developed before 1926 were rarely restricted by property records. Instead, they were restricted by social means. Realtors, abiding by the Code of Ethics, refused to show properties to families of color. If that was not enough, intimidation tactics and violence greeted any Black or Asian family who dared rent or buy in a white neighborhood.

Redlining

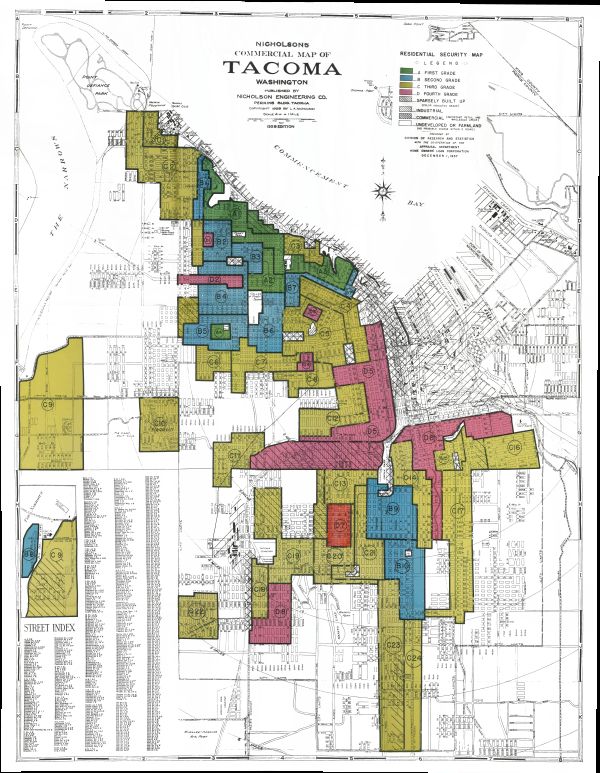

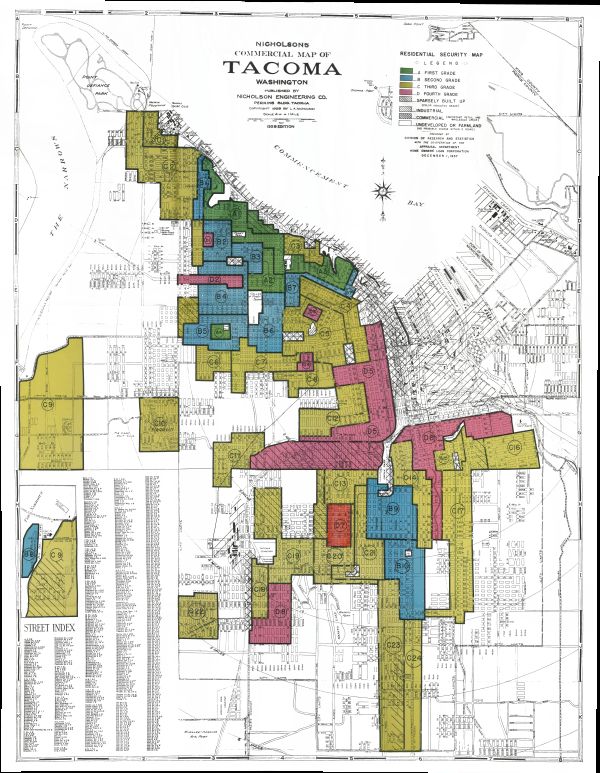

1937 redlining map produced by the Home Owners Loan Corporation. Click to see map details

1937 redlining map produced by the Home Owners Loan Corporation. Click to see map details

The spread of restrictive covenants after Corrigan was complemented by redlining discrimination by banks and mortgage lenders encouraged by federal agencies beginning in the mid-1930s. The Roosevelt Administration created the Homeowners Loan Corporation (HOLC) and the Federal Housing Agency (FHA) as part of the New Deal plan to rescue the housing market that had collapsed in the Great Depression. The two agencies encouraged banks to resume lending while rescuing homeowners facing foreclosure. The HOLC purchased existing mortgages and issued new ones with longer repayment schedules.[21] But to minimize risk, the HOLC hired realtors to create color-coded residential security maps of urban areas across the country, to show lenders where investments were safe and where they were not.

Neighborhoods were assigned a green, blue, yellow, or red color grade based on factors such as proximity to industry, housing conditions, and the racial composition of the area. Areas with Black residents were automatically given a red, or “hazardous,” grade. The map of Tacoma, created in 1937, reflected these grim discriminatory practices. Only 4% of the city received a green grade, designated for neighborhoods with a homogenous white population. Thirteen percent of the city was graded as “still desirable” (blue), while 51% was classified as “definitely declining” (yellow). Thirteen percent of the city was deemed “hazardous” (red). The historically Black Hilltop neighborhood and Japantown were lumped together in the grading. The area was specifically downgraded for its “cheap apartment complexes” and what the map’s creators described as an “inharmonious population, much of which is in the lower strata.”[22]

These racist designations severely limited access to homeownership and wealth building opportunities for people in redlined areas for generations to come. Even though redlining practices were banned under federal and state law in the 1970s, discriminatory lending practices remain a problem still today.

War and Postwar

Founded in 1928, the Japanese American Citizens League was modeled after the NAACP. Members of the Tacoma chapter meet in 1937. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

Founded in 1928, the Japanese American Citizens League was modeled after the NAACP. Members of the Tacoma chapter meet in 1937. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

By the time the HOLC created their map of Tacoma in 1937, the Japanese community had already created a robust community downtown concentrated in eight blocks between Tacoma and Pacific Avenue between 11th and 19th street.[23] In 1920, the city counted 168 Japanese-run businesses. By 1940, that number had grown to 251.[24]

The community’s prosperity was abruptly disrupted in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Between March and August of 1942, the United States sent 112,000 Japanese people to internment camps. On March 28th, 1942, Caucasian carpenters started construction on a temporary barracks structure on the Puyallup Fair Ground. Seventeen days later, the fairgrounds had been completely transformed – 380 buildings were erected to house 8,000 Japanese people. On May 9th, soldiers hung posters outlining Exclusion Order 58 all around the city.

The devastation for Tacoma's Japanese community was irreversible. When internees returned after the war, they found their lives had been systematically dismantled. Their homes were looted, their businesses were destroyed, and the social fabric of their community was gone. Very few of the 169 business owners in the community had enough capital to restart. By 1950, only 174 of the 872 Japanese residents who had called Tacoma home before the war had returned.[25] Many families restarted their lives in other states. The community's infrastructure – its school, newspaper, card houses, social gathering places, and economic networks – was completely gone.

Black troops based at Fort Lewis were segregated into separate units and accomodations. Couples dance at the segregated USO facility in downtown Tacoma in 1944. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

Black troops based at Fort Lewis were segregated into separate units and accomodations. Couples dance at the segregated USO facility in downtown Tacoma in 1944. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

The Black population of Tacoma and Pierce was growing as the Japanese community disappeared. Jobs in shipyards and other defense industry attracted migrants, and Black soldiers stationed in Fort Lewis and Base McCord sometimes brought families and decided to remain in the area after the war. But white resistance and housing exclusions made this difficult.

As a result of decades of racial restrictive covenants, redlining, and the actions of realtors, most of Tacoma’s population of color was segregated into a few select areas. In 1950, the population of Pierce County was 226,649, 97% of whom were white. The city was home to only 3,633 Black residents and 2,005 persons who were identified in the 1950 census as “other races.” The Black population was concentrated to three main places – the Hilltop neighborhood and area around the shipyard, Salishan – the public housing project created for the war effort, and the McChord military base. “Other races” which included both Indigenous Americans and Asian Americans, were similarly concentrated around Hilltop and the shipyard, Salishan and the Puyallup reservation around Fife.

Resistance/Enforcement

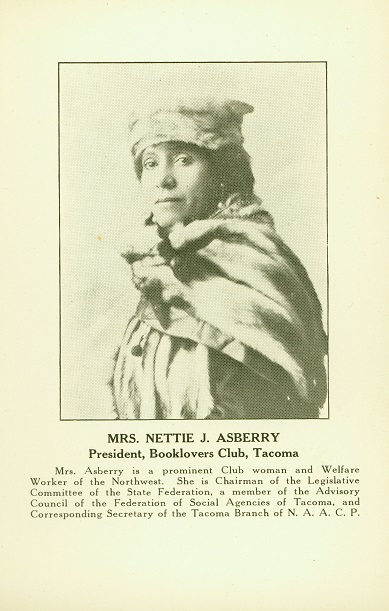

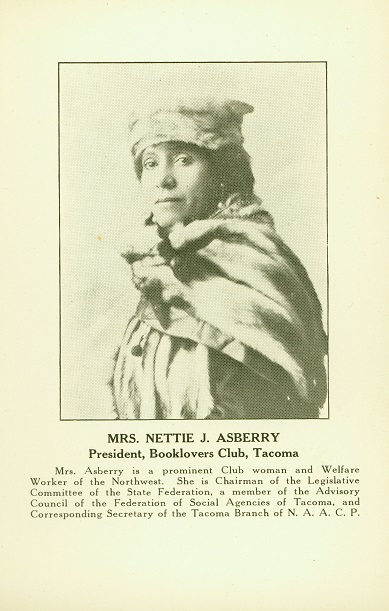

Nettie Asberry led Tacoma's NAACP chapter (the first on the west coast) after its founding in 1913.(photo: Washington State Archives)

Nettie Asberry led Tacoma's NAACP chapter (the first on the west coast) after its founding in 1913.(photo: Washington State Archives)

Black residents of Tacoma had founded an NAACP chapter in 1913, one of the first chapters in the country. Led by Nettie J. Asberry, the chapter contested discrimination through public campaigns and lobbying city officials, trying to enforce the 1890 Public Accommodations Act that John Conna had fought for. It is not clear whether the chapter filed lawsuits of the sort that Conna won in 1891. But the chapter’s proximity to Olympia meant that members could lobby and testify before the state legislature. In 1935 and again in 1937, Tacoma and Seattle NAACP members and other progressive organizations managed to defeat two bills that would have made racial intermarriage illegal in Washington.[26]

In 1949, after several years of lobbying by Black activists and their allies, the state legislature passed the Washington Law Against Employment Discrimination declaring that “The opportunity to obtain employment without discrimination

because of race, creed, color declared national to be origin is hereby

recognized as and declared to be a civil right.” Modeled after legislation in New York and several other states, the law established the Washington State Board Against Discrimination to monitor compliance but unfortunately provided no significant penalties or enforcement mechanisms. Nor did it address the issue of housing discrimination.

The US Supreme Court had adjusted the legality of racial restrictive covenants in 1948. In the Shelley v. Kramer case brought by the national NAACP concerning properties restricted in St. Louis, the court decided that covenants remained legal as private agreements but could not be enforced in courts of law because that would violate the 14th amendment provision requiring states to insure “equal protection” under state laws.

The Shelley decision did little to ease systematic housing discrimination in Tacoma. On April 30th, 1949, at the Washington State Conference of Branches of the NAACP, Tacoma Board of Directors member Mrs. Worther G. Hamilton discussed the housing crisis in Tacoma, explaining, “In Tacoma, minorities can now only buy in undesirable areas, and can get into good areas only on rare occasions. A minority can phone into a real estate dealer and get a promise of a home at a certain price. But, when that person arrives to complete the sale or arrangement, various excuses are given as to why they cannot have the house.”[27]

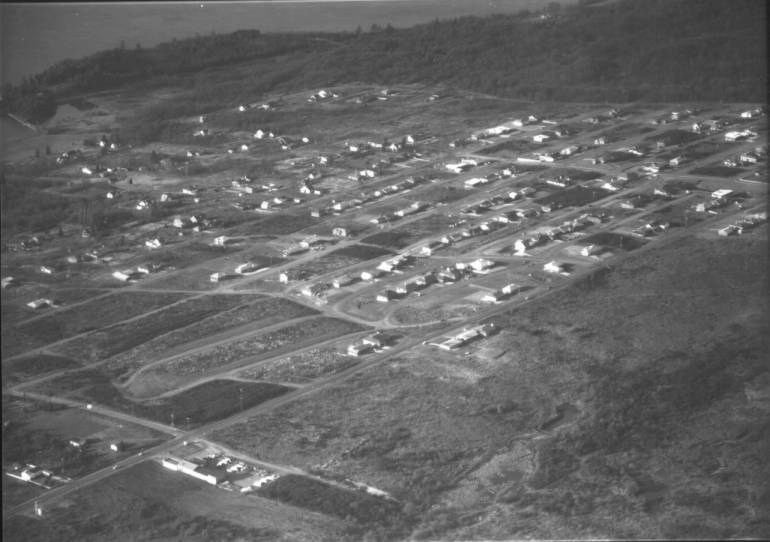

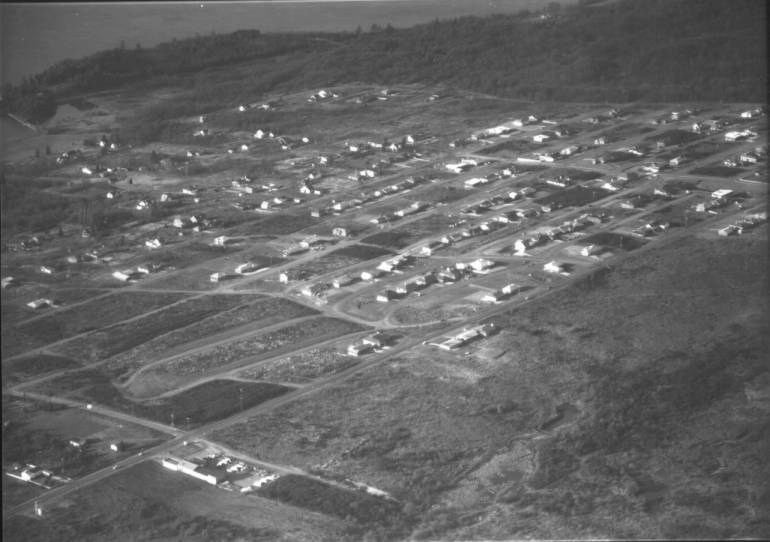

Narrowmoor from the air 1951. The subdivisions were developed and sold by Elvind and Aslaug Anderson with restrictions aimed at Black and Asian Americans. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

Narrowmoor from the air 1951. The subdivisions were developed and sold by Elvind and Aslaug Anderson with restrictions aimed at Black and Asian Americans. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)-

"The street of Dreams" in a Lakewood subdivision developed by the March Company in 1952. Much of Lakewood was developed with racist restrictions. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

"The street of Dreams" in a Lakewood subdivision developed by the March Company in 1952. Much of Lakewood was developed with racist restrictions. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

Moreover, developers continued to add new racial restrictive covenants. Norton Clapp, a developer who specialized in the Lakewood area, added several new subdivisions in the 1950s, each declaring that “No persons except persons who shall be of the Caucasian race shall be allowed to purchase, nor allowed to use or occupy said property or any part thereof, except in the capacity of domestic servants, chauffeurs or employees of the occupants thereof.” H.A. Briggs joined with Puget Sound National Bank to develop 170 parcels in north Tacoma in 1950 using the same restriction. Elvind and Aslaug Anderson had begun developing Narrowmoor subdivisions in the 1940s, advertising them as “Tacoma’s Finest Exclusive Residential Area.” In 1955, they added a fourth subdivision again with a provision that prevented sale or occupancy to anyone of “Asiatic or African” descent.[28]

In the 1950s as the climate of legal and public opinion began to shift, leaders of the Tacoma Board of Realtors discussed how to proceed. At their weekly meeting on September 20th, 1957, Attorney Clarence E. Layton came to discuss the legality of restrictive covenants. Of the 1948 Shelley v. Kramer Supreme Court case, he explained, racial restrictive covenants are valid but are not enforceable through the state courts and are only valid if agreed to voluntarily. His advice: to leave them out whenever possible and instead to enforce exclusion by other means such as telling “undesirable” prospective buyers that “somebody else signed the earnest money agreement first.”[29] Mr. Layton’s advice is telling of the culture of real estate in Tacoma and the covert manner in which TREB continued to enforce segregation. Even after Layon spoke to the Tacoma Real Estate Board, new restrictions were added in Pierce County throughout the early 1960s.

A Discouraging Fight for Open Housing

In 1968, after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, 1,000 Tacomans marched to the County-City Building in his honor and calling for Tacoma to pass an open housing law. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

In 1968, after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, 1,000 Tacomans marched to the County-City Building in his honor and calling for Tacoma to pass an open housing law. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

By 1960, the racial inequity in Tacoma was painfully evident. Most of Tacoma’s Black population was concentrated between two neighborhoods, Hilltop and Downtown (The McCarver District) and the Salishan Public Housing Project on the Eastside. Census data revealed alarming disparities: The residents in the McCarver District had the lowest level of education in the city (a median of nine years for residents over 25), the lowest family income in the city (less than $4,000 annually) and between 25% and 50% of the houses were deemed “deteriorated or dilapidated” by census takers.[30] The dire situation set the state for the tumultuous fight for Open Housing.

In 1960, Clara Goering proposed Tacoma’s first Open Housing Ordinance, but it failed to gain enough support to make it to the City Council.[31] Undeterred, the NAACP continued to press forward. On February 25th, 1961, before the Washington State Legislature’s 37th Session, the NAACP organized a statewide rally for Open Housing at the Capitol Building. They invited everyone who could come to join them and urged people to carpool with their friends and neighbors.[32] Despite these efforts, a proposed statewide open housing bill was defeated in the legislature. By the end of November 1961, the NAACP declared that Open Housing was one of their principal concerns and that Open Housing should be pursued in all areas of the city and state.

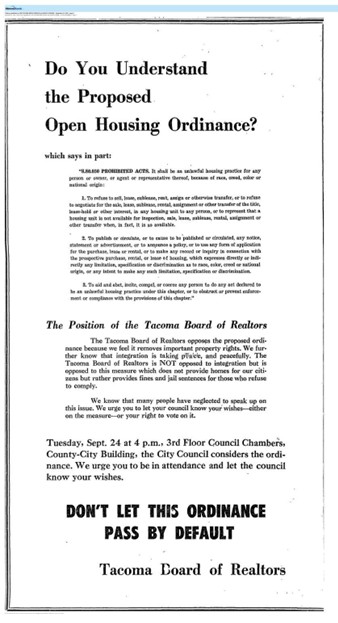

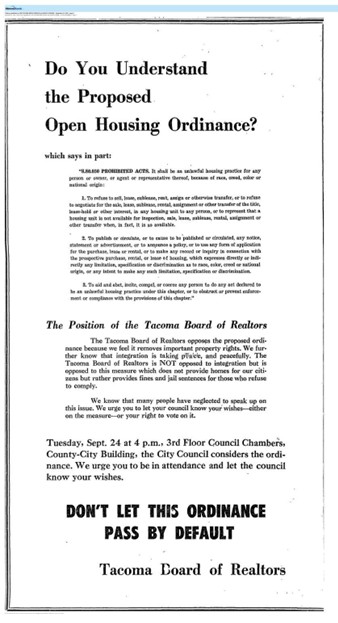

Tacoma Real Estate Board advertisement against the proposed Open Housing ordinance, September 22, 1963

Tacoma Real Estate Board advertisement against the proposed Open Housing ordinance, September 22, 1963

From the outset, the Tacoma Real Estate Board (TREB) ardently opposed Open Housing proposals. At a 1963 fact-finding session held by the Washington State Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, TREB President Gordon C. Fors described Tacoma’s racial situation as “not too bad.”[33] This was in stark contrast to the NAACP's President Jack Tanner, who presented grim evidence of systemic discrimination and economic exclusion faced by Tacoma’s Black residents.

The debate came to a head in September 1963 when Tacoma’s City Council prepared to vote on a landmark Open Housing Ordinance. In a last-ditch effort to block the legislation, TREB took out a nearly full-page advertisement in The News Tribune framing the ordinance as an attack on free speech and private property rights and urging citizens to oppose the ordinance.

On the evening of September 24th, 1963, Tacoma’s City Council passed the landmark Open Housing Ordinance in a 7-2 vote, but the victory was short-lived. As the last vote was cast, Fors announced TREB was contemplating a referendum to reverse the legislation.[34] The next day, the realtors met behind closed doors and unanimously voted to pursue a referendum.

The Real Estate Board’s campaign was extraordinarily effective. By October 2nd, 11,495 Tacomans had signed the petition and by October 5th, the petition had 15,534 signatures – well over the 4,257 needed to put the ordinance on the ballot.[35] Tacoma’s Open Housing Ordinance would now face a public vote. On February 12, 1964, voters rejected Open Housing by a three to one margin.[36]

Cross Burnings in the City of Destiny

In the aftermath, realtors and white neighborhoods continued to enforce exclusion and segregation. Indeed, violence as a tool of segregation escalated. In 1965 and 1966, a series of cross-burnings shook the city. On October 10th, the Tacoma News Tribune reported a gasoline-soaked cross was burned on the lawn of a Black Sergeant and his family in the South End.[37] Earlier that summer a cross was set on fire on the lawn of a home in University Place. On May 22nd, 1966, the Tribune reported a cross burning on the lawn of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Baker at 3015 N. Proctor St.[38] Both white, Mr. Baker was on the executive Board of the NAACP and his wife was the Branch’s Direct Action Coordinator. It was the fifth of seven cross-burnings in seven weeks. The Tacoma NAACP accused City officials of not being proactive enough, an accusation Tacoma Mayor Harold M. Tollefson adamantly denied and stated the city “had no real racial problem.”[39]

Three days after the report of the cross burning on the Baker lawn, seven teenage boys admitted to the incident of terror, one cross-burning on the grounds of the predominantly Black Lowell Elementary School and two separate burnings on the lawn of a black family at South 70th and Clement.[40] Two weeks later, an unrelated 16 year old boy confessed to orchestrating two cross burnings in the previous year.[41] Tacoma City officials, the Police department and the Tacoma News Tribune promptly dismissed the cross-burnings as pranks by the teenage boys. Several more went unaccounted for including one later that summer on the lawn of Maurice Ivery at 6616 48th St. W in University Place.

In Tacoma, in 1965, in a city with a population of 7,500 Black people, there were less than 10 Black businessmen, less than 10 skilled laborers, 3 black policemen, no firemen, school principals, government administrators and assistants, college professors and city inspectors.[42] The lack of representation in Tacoma not only illustrates the barriers Black residents faced in gaining certain types of employment but the consensus of racism in the County – especially in the face of incidents of race terror like cross burnings.

A Victory for Open Housing

The fight for open housing in Tacoma regained momentum after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in April 1968. On the Sunday after his death, 1,000 Tacomans marched to the County-City Building in his honor. On the steps, Frank Russell, president of Tacoma’s NAACP chapter, urged the City Council to immediately adopt an open housing ordinance.[43] Just days later, on April 11, Congress passed the 1968 Fair Housing Act, a three-stage federal law set to take full effect in 1970 that prohibited housing discrimination on the basis of race, religion, national origin, and sex.

Mayor Rasmussen believed Tacoma needed an open housing ordinance, but City Council meetings in the following weeks shifted focus. The debate no longer centered on individual liberties like it had four years prior but on whether an emergency clause was necessary, given the new federal law. In a surprising turn, even Earl Manlock, president of the Tacoma Real Estate Board, publicly supported immediate action.[44]

Seattle passed its open housing ordinance with an emergency clause just a week after Congress passed the federal act.[45] Tacoma soon followed. On April 31, after six hours of debate, the City Council voted 6-3 to pass an emergency open housing ordinance.[46] The law, which officially banned housing discrimination based on race, creed, or color, took effect two days later, on May 2.

Conclusion

The passage of Tacoma’s Open Housing ordinance was a significant legal victory for the city, but it came nearly 80 years after John N. Conna tested Washington’s Public Accommodations Act. Conna’s legal battle against discrimination at the New York Kitchen represented a fleeting moment of progress. In the intervening decades, discrimination evolved into insidious forms– embedded into exclusionary federal policies, property deeds, and real estate practices. The same city that celebrated Conna’s political position and accepted his family’s gift of land would systematically exclude families like him from most neighborhoods through redlining and restrictive covenants.

Sophia Dowling was Project Manager for the Racial Restrictive Covenants Project 2022-2024

[1] Gary Fuller Reese, Who We Are: An Informal History of Tacoma’s Black Community before World War One, (Tacoma: Tacoma Public Library, 1992), 17.

[2] Fuller Reese, Who We Are, 15.

[5] Plat filed by Joseph Conna with the Pierce County Auditor’s Office, 24 December 1889.

[6] Kit Oldham, “South Puget Sound Tribes Sign Treaty of Medicine Creek on December 26,” HistoryLink, September 12, 2022, https://www.historylink.org/file/5254.

[7] Murray Morgan, Puget’s Sound: A Narrative of Early Tacoma and the Southern Sound (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2018), 117.

[8] Morgan,Puget’s Sound, 117.

[9] Miguel Douglas, “Puyallup Land Claims Settlement (1990)”, HistoryLink, October 12, 2016,

[10] Caroline Gallacci, “Planning the City of Destiny: An Urban History of Tacoma to 1930” PhD diss., (University of Washington, 1999), 128.

[11]Ronald Magden, >Furusato: Tacoma-Pierce County Japanese, 1888-1977 (Tacoma, Wash.: Tacoma Longshore Book & Research Committee, 1998), 9.

[12] Gallacci, “Planning the City of Destiny,” 173.

[13] Morgan, Puget’s Sound, 287.

[16] Charles Williams, “Labor Radicalism and the Local Politics of Chinese Exclusion: Mayor Jacob Weisbach and the Tacoma Chinese Expulsion of 1885,” Labor History 60 (6): 685.

[17]Lisa M Hoffman and Mary L Hanneman, Becoming Nisei: Japanese American Urban Lives in Prewar Tacoma, 1st ed. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2020).

[18] Covenant for Pacific City, 20 March 1907. Database of Racial Restrictive Covenants.

[19] Clement E. Vose, Caucasians Only: The Supreme Court, the NAACP, and the Restrictive Covenants Cases, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1959), 17-19.

[20]National Association of Real Estate Boards. Code of Ethics. Chicago, IL: National Association of Real Estate Boards, 1924.

[21] Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, (New York London: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2018), 63-64.

[22] Robert K. Nelson and LaDale Winling, Map of Tacoma, Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America,” accessed February 23, 2025,

[23] Hoffman and Hanneman, Becoming Nisei, 17.

[26] Stephanie Johnson, “Blocking Racial Intermarriage Laws in 1935 and 1937,” Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project.

[27] Reports from Group Discussion Sessions, 30 April 1949, NAACP Papers, Part 26: Selected Branch Files, 1940-1955, Library of Congress,

[28] Covenant for Narrowmoor, 1944. Database of Racial Restrictive Covenants.

[29] “Realtors Hear Restriction Talk,” The Tacoma News Tribune, September 21, 1957.

[30] Murray Morgan, “Tacoma’s Hilltop Ghetto: Lovely Vista, Lousy Housing,” Seattle Magazine, October 1965, 17.

[31] Anthony Long, “Redlining, Racial Covenants, and Housing Discrimination in Tacoma,” HistoryLink, 12 June 2024,

[32] “Civil Rights Rally at Rotunda of State Capitol”, 25 February 1961, NAACP Papers, Part 25: Branch Department Files, 1941-1965; Newsletters, Branches (by State). Library of Congress,

[33] “Disagreement Shown at Hearing On Rights,” Tacoma News Tribune, January 22, 1963.

[34] “Fors Expects 5,000 Names on Petition,” Tacoma News Tribune, September 27, 1963.

[35] “11,495 Sign Petitions For Referendum,” Tacoma News Tribune, October 2, 1963.

[36] “Tacoma Voters Reject Open Housing Measure,” Los Angeles Times, February 13, 1964.

[37] “Police Report Cross Burning,” Tacoma News Tribune, October 20, 1965.

[38] “Evans Blasts ‘Bigots’ In Cross-Burning,” Tacoma News Tribune, May 24, 1966.

[39] “Mayor Denies Charges On Racial Problems,” Tacoma News Tribune, May 23, 1966.

[40] “7 Students Admit to Cross-Burning,” Tacoma News Tribune, May 25, 1966.

[41] “Youth Accused in Cross Burnings,” Tacoma News Tribune, June 9, 1966.

[42] Tacoma Branch Newsletter, December 1965, NAACP Papers, Part 25: Branch Department Files, 1941-1965, Washington, Seattle, Tacoma branch newsletters and printed materials, 1961-1965. Library of Congress,

[43] Rod Cardwell, “Tacoma Marchers Pay Tribute to Dr. King,” Tacoma News Tribune, April 8, 1968.

[44] Rod Cardwell, “City Delays Housing; Realtors Ask for Law,” Tacoma News Tribune, April 24, 1968.

[45] “Seattle Votes Emergency Housing,” Tacoma News Tribune, April 20, 1968.

[46] Rod Cardwell, “Housing Law Goes on Books; Emergency Control Passes” Tacoma News Tribune, May 1, 1968.

Notice how affordable homes were for White families in the decades after WW2. A $285 down paymment in 1950 is equivalent to about $4,000 in 2025. Albert Balch developed many subdivisions in Pierce, King, and Snohomish counties that were bound by restrictive covenants preventing the sale, lease, or occupation by anyone other than "Caucasians". (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

Notice how affordable homes were for White families in the decades after WW2. A $285 down paymment in 1950 is equivalent to about $4,000 in 2025. Albert Balch developed many subdivisions in Pierce, King, and Snohomish counties that were bound by restrictive covenants preventing the sale, lease, or occupation by anyone other than "Caucasians". (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)  selection from 1876 map by Department of the Interior shows tribal reservations and original tribal territories. Notice the area designated for the Puyallup reservation which includes much of present-day Tacoma and Fife. Despite the treaty, these lands would later be seized.

selection from 1876 map by Department of the Interior shows tribal reservations and original tribal territories. Notice the area designated for the Puyallup reservation which includes much of present-day Tacoma and Fife. Despite the treaty, these lands would later be seized.  Mayor Jacob Weisbach led the "driving out" actions in Tacoma that destroyed the Chinese settlement.

Mayor Jacob Weisbach led the "driving out" actions in Tacoma that destroyed the Chinese settlement.

Ward Smith served as president of the Tacoma Board of Realtors as well as many other influential positions. His company routinely imposed racist restrictions in deeds while refusing to show properties to families of color. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

Ward Smith served as president of the Tacoma Board of Realtors as well as many other influential positions. His company routinely imposed racist restrictions in deeds while refusing to show properties to families of color. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

Founded in 1928, the Japanese American Citizens League was modeled after the NAACP. Members of the Tacoma chapter meet in 1937. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

Founded in 1928, the Japanese American Citizens League was modeled after the NAACP. Members of the Tacoma chapter meet in 1937. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections) Black troops based at Fort Lewis were segregated into separate units and accomodations. Couples dance at the segregated USO facility in downtown Tacoma in 1944. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

Black troops based at Fort Lewis were segregated into separate units and accomodations. Couples dance at the segregated USO facility in downtown Tacoma in 1944. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections) Nettie Asberry led Tacoma's NAACP chapter (the first on the west coast) after its founding in 1913.(photo: Washington State Archives)

Nettie Asberry led Tacoma's NAACP chapter (the first on the west coast) after its founding in 1913.(photo: Washington State Archives) Narrowmoor from the air 1951. The subdivisions were developed and sold by Elvind and Aslaug Anderson with restrictions aimed at Black and Asian Americans. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

Narrowmoor from the air 1951. The subdivisions were developed and sold by Elvind and Aslaug Anderson with restrictions aimed at Black and Asian Americans. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections) "The street of Dreams" in a Lakewood subdivision developed by the March Company in 1952. Much of Lakewood was developed with racist restrictions. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

"The street of Dreams" in a Lakewood subdivision developed by the March Company in 1952. Much of Lakewood was developed with racist restrictions. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections) In 1968, after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, 1,000 Tacomans marched to the County-City Building in his honor and calling for Tacoma to pass an open housing law. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections)

In 1968, after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, 1,000 Tacomans marched to the County-City Building in his honor and calling for Tacoma to pass an open housing law. (photo: Tacoma Public Library digital collections) Tacoma Real Estate Board advertisement against the proposed Open Housing ordinance, September 22, 1963

Tacoma Real Estate Board advertisement against the proposed Open Housing ordinance, September 22, 1963