Autumn 2010- Winter 2011

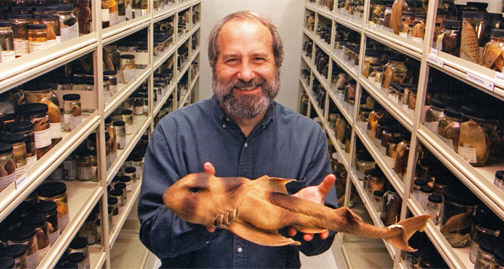

The Curious Case of Ted Pietsch

MS 1969, University of Southern California (USC)

PhD 1973, USC: The osteology and relationships of ceratioid anglerfishes of the family Oneirodidae with a review of the genus Oneirodes Lütken

Ted Pietsch joined the SAFS faculty in 1978. He conducts research on marine ichthyology, including biosystematics, zoogeography, and behavior of deep-sea fishes. He is also curator of the Fish Collection of the UW Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture (uwfishcollection.org).

Robin Layton, Seattle Post-Intelligencer

Ted was born in Royal Oak, Michigan, and earned a BS in Zoology at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor. He noted that his entrepreneurial activities as a youth, raising zebrafish and earthworms for local aquarium and bait shops, likely influenced his direction in college. Initially interested in herpetology, Ted found his true calling in graduate school at University of Southern California, where he discovered anglerfishes. He said, “I took one look and got hooked!”

Ted’s career took on an added dimension in the 1980s, when he started to pursue historical studies of aquatic organisms and the people who wrote about them, including Peter Artedi, Georges Cuvier, Carl Linnaeus, Charles Plumier, and Louis Renard. He has published numerous books that demonstrate his interest in the historical. This curiosity is particularly evident when you walk into his office, which is filled with bones, fossils, and artifacts dating back to early human history.

MD: Why are anglerfishes so interesting?

TP: Below 1,000 meters, they are the most species rich groupof vertebrates in the deep ocean (11 families and some160 species), yet they are extremely rare. Even where they are most concentrated, we estimate only one anglerfish every 30 meters.

Anglerfishes include species with males that are a fractionof the size of the females. To reproduce, the male bites onto the female, their tissues fuse, and he becomes a permanent parasite. The male feeds off the nutrients in her blood and she carries him around for life.

Yet, not all deep-sea anglerfishes exhibit this complex adaptation of sexual parasitism. It only occurs in 4 of the 11 families, and we’d always assumed that these 4 all evolved together. But, through phylogenetic analysis, we now know that this parasitism has evolved independently within the group as many as five times. This is really astounding!

No other animals share bodily fluids, a fact that has profound biomedical implications: For example, there isno tissue rejection. The male and female are of totally different parental lineages, yet they fuse tissue and blood…immunologically, this is amazing.

MD: You spent 10 years studying the biodiversity of the Kuril Islands in the Russian Far East.

TP: There was no information on plant and animal assemblages on these islands. With National Science Foundation (NSF) funding, we collaborated with Russian and Japanese scientists, conducting 10 annual summer expeditions with a staff of 35 people working from a Russian research vessel. Our work yielded more than 160 publications and an international symposium held in Sapporo, Japan, in 2001.

We discovered 46 species new to science. And we stumbled upon pottery, stone axes, arrowheads, and other relics in the sides of cliffs worn away by the ocean. The remains were attributed to human cultures dating back 50,000 years and more! This discovery launched a major NSF-funded project by the UW Department of Anthropology.

MD: There’s Ted Pietsch, the curator, taxonomist, and systematist. Then there’s also Ted Pietsch, the historian.

TP: I started to pursue historical research in the early 1980s. From deep-sea anglerfishes, I became interested in their relatives, shallow-water frogfishes. I discovered an old drawing of a frogfish (below), which really captivated me.

This led to my doing extensive research on Louis Renard—an 18th century bookdealer, seller of medicinals, and secret agent—and publishing a large volume titled Fishes, Crayfishes, and Crabs: Louis Renard and His Natural History of the Rarest Curiosities of the Seas of the Indies in 1995. More recently, I published a book on oceanic anglerfishes, another on fishes of the East Indies, and I’m just now finishing a book, with translation help from staff member, Beatrice Marx, on the history of the natural sciences.

MD: What motivated you to undertake these projects?

TP: It’s a lot of fun, and aside from the esthetic value, historical studies often contribute in unexpected ways. For example, there’s a species called Histrio histrio, named by Linnaeus in the first edition of his Systema Naturae of 1758. Through careful historical research, we’ve discovered that he based his description not on a single species but on a complex mix of different things. We were able to sort out all the different species—critical information to conservation and management related issues.

MD: Recently, you added a new dimension to your historical studies with the publication of a “hard fiction” book, The Curious Death of Peter Artedi: A Mystery in the History of Science.

TP: This book is 95% factual—I only added a few small twists and turns to support a history that might have been:

Linnaeus and Artedi met in college in the early 1700s. Given similar interests, they worked together, with Linnaeus studying plants and Artedi pursuing fishes. When Artedi was about to publish his monograph on fishes, he wound up dead in an Amsterdam canal.

Artedi and Linnaeus had promised that if anything happened to one of them, the other would see that their work was published. Linnaeus did publish all of Artedi’s manuscripts, but he waited three years to do so! In the interim, he published his own work, using Artedi’s approaches and methodology in his books on plants.

Understand, this was an implication, not proof of wrongdoing. Even so, why would Linnaeus wait so long to publish Artedi’s works? And why would he allow Artedi to be buried as a pauper, in an unmarked grave? The obvious answer is he wanted to be first to publish the innovative ideas that Artedi had come up with, and to make sure that Artedi was forgotten while his own legacy would be assured for future generations.

So there’s good reason to believe that Artedi’s death benefited Linnaeus enormously. And this creates a good premise for delving into some fiction. Every ichthyologist hears this story, and no one has ever suggested it was anything but an accident; yet, I really don’t think it was an accident.