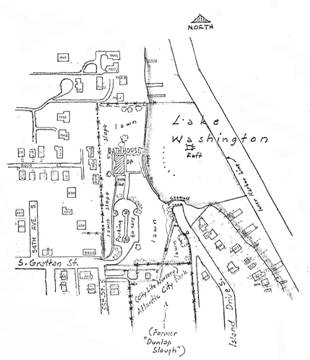

SITE HISTORY Pritchard Beach was originally known as the Dunlap Slough. The City of Seattle acquired Pritchard Beach in 1910. The opening of the Ship Canal in 1917 lowered Lake Washington and as a result drained the slough, exposing the lake bottom. Culverts were placed among the remnants of the slough to drain runoff to the south end of the beach. Eventually, the site became soggy and unusable. In 1954, the City of Seattle leased the marshland to Seattle City Light for use as a plant nursery and equipment storage. (See image 1.)

Over the years, it became abandoned and overgrown with blackberry. In 1996, the land returned to the jurisdiction of the City of Seattle’s Department of Parks and Recreation. Residents of the neighborhood organized and collaborated with community agencies and organizations to reclaim the site as a natural wetland/learning environment. The community approached the Starflower Foundation for support, and Starflower Foundation, having worked with landscape architect Charles Anderson on similar projects, approached his firm Anderson and Ray to design the site. In addition to securing funding from the Starflower Foundation for design and construction, the community pursued and received financial support form the City of Seattle’s Department of Neighborhoods Matching Fund Grant, King County Water Quality Block Grant, and King County Urban Reforestation and Habitat Restoration Grant.

PROJECT DESIGN Landscape Architect Charles Anderson used the hydrology and buried physiology of the site to guide the design of five urban wetland habitats: an informal Wet Meadow in traditional park-space , an Alder Gallery, a Gateway of scrub-shrub thicket, a model for an urban Wet Meadow, and an Upland Overlook of a wooded, forested edge. Each of the five habitats reintroduces native plants to the abandoned site. A variety of plant textures and compositions distinguish the experience, sensory qualities, and educational opportunities of each wetland habitat.

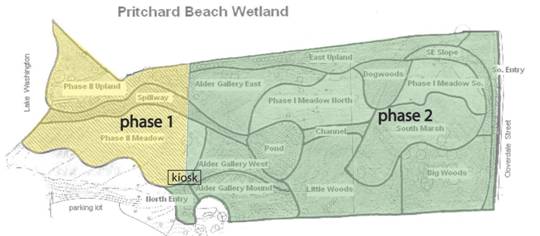

CONSTRUCTION PROCESS Overview A key to the success of the construction process was effective communication of with residents in the neighborhood. The construction crew notified residents when and what type of construction activities would occur. Keeping residents informed eliminated complaints and helped to keep them supportive of the project. The construction of the site was completed in two phases. (See image 2.) The first phase focused on the area south of the kiosk and included the initial reshaping of the site, the removal of a greenhouse the removal of fill material, and the creation of the pond, amphitheater and pathways. The second phase focused on the area north of the kiosk and included the creation of the wet meadow, and finished work not yet completed from phase one, the construction of the boardwalk and completion of the amphitheater. A third phase of construction has yet to be completed due to lack of funding but would include the construction of viewing piers, educational signage, a rocks/logs play area, the installation of donor plaques along the delineation strip between the meadow and park turf areas, and the construction of a pedestrian boardwalk to the south of the pond.

Site Preparation and Erosion Control The demolition firm Nuprecon performed the first tasks on site, stripping the top eight inches of the soil to remove invasives, and removing layers of gravel used in the equipment storage area. They completed the excavation and grading of the site during the dry season (early summer), which reduced the potential amount of surface runoff and erosion. Silt fences, mulch, coir logs, and a cover crop of sterile wheat and barley were used during the site preparation and construction process to prevent erosion and sedimentation.

Highlight: Reuse of Materials The layers of gravel removed during the excavation of the site were reused to build pathway ramps and in the uplands area. Non native vegetation that was cleared and grubbed was used in the creation of the mound upon which the amphitheater is built. Soil removed during the construction of the pond was transported to nearby Genesee Park and used to build Mound #3 at Genesee Meadow. Rocks collected from the site were added to those used to construct the “box of rocks” amphitheater. (See image 3.)

Grading and Earth Work After the excavation/site preparation phase, landscape contractor, Head First, graded the site to create the five wetland areas. Head First reused the soil graded from the wetlands to construct the uplands areas. The landscape architect performed the fine grading of the ponds and the stream connecting the wetlands to Lake Washington.

Highlight: the Battle Over the Nine-foot Deep Pond

One of the major challenges during the construction process was the depth of the main wetland pond. (See image 4). The approved construction documents called for a nine-foot deep pond as designed by the landscape architect. It wasn’t until after its excavation that the parks department ordered the pond be no greater than eighteen inches deep due to safety reasons. The landscape architect successfully defended the design and functions of the pond’s depth to manage and filter runoff and create high quality habitat for birds and frogs.

Planting practices With the entire site cleared, it was necessary to replant in a cost-effective manner and prevent the reestablishment of invasive species. Fast-growing alder and maple species were densely planted to quickly establish a canopy layer to shade out invasive under-story plants. Smaller slower-growing conifers were planted amongst the alders and maples to establish a conifer under-story. The landscape architect also experimented with establishing native plant communities in ‘islands’ and by using a grid pattern in the meadow area. A significant resource to the planting of the site was the commitment of community volunteers. Over the years, they have planted more than 1500 native plants. Highlight: Island/Grid Planting Due to a limited budget, it was not feasible to densely plant the entire site. In the areas without dense over story plantings, the landscape architect created a grid with landscape fabric and densely planted the remaining exposed “islands” (see image 5). Each island contains a combination of native plant species appropriate for upland and lowland wetlands. Serving as an experiment, the success or failure of the various plant communities will provide feedback on how to establish wetland vegetation communities.

The landscape architect’s and client’s views differed in their restoration planting methodologies. The landscape architect’s approach is to set up a foundation/framework that supports and allows the desired native plant communities to establish themselves. Alternatively, his client’s approach is to establish the desired native plants as soon as possible. An example: cattails have begun to compete with the desired native bulrushes around the main wetland area. The landscape architect has accepted the cattails, and concludes that the bulrushes have had a few years to establish themselves with little success. However, the client would prefer that the cattails be removed and the bulrushes replanted.

Maintenance Since its completion, the Starflower Foundation has maintained and monitored Pritchard Beach Wetland. In addition, the non-profit organization, Friends of Pritchard Beach, organizes volunteer planting parties and leads educational programs in the park. In 2007, Starflower Foundation will complete their oversight responsibilities and turn the wetland maintenance over to the parks department. Given the current financial constraints of the parks department, there are concerns that it will be difficult for them to provide the necessary resources to maintain the site as the Starflower Foundation is doing currently. Additionally, community volunteers and resources have diminished over the past year.

Highlight: Starflower Foundation Founded in 1996, the mission of the Starflower Foundation is to assist the “creation rehabilitation and stewardship of Pacific Northwest native plant communities by supporting citizen-driven restoration and education projects that inspire understanding, appreciation and preservation of Pacific Northwest native ecosystems with humans as an integral part of these ecosystems” (www.starflower.org). The Starflower Foundation funded the design and construction of Pritchard Beach Wetlands, maintained restoration efforts since its construction in 1996, and offered technical assistance to Friends of Pritchard Beach. The Starflower Foundation has funded similar community projects such as Roxhill Bog and Greg Davis Park.

Conclusion With all projects, there are challenges. Despite a few challenges - defending the depth of the main pond, differing restoration approaches, and limited and uncertain resources for future maintenance of the site – there are indications that Pritchard Beach Wetland is a successful model for wetland habitats in the urban landscape. The design of the site reflects the community’s desire for a natural wetland/learning environment. The construction of the site is true to the design. The wetlands were successfully constructed and are functioning as they were designed. The sequence of wetland pools slows and filters runoff before it enters Lake Washington. The native vegetation has successfully established itself despite lack of an irrigation system. With the establishment of native plant communities, the wetland habitats have supported a burgeoning population of birds, amphibians, and small mammals. A concert of chorus tree frogs, the recent sighting of a green heron, and the antics of a pair of muskrats reflect the quality of habitat that is evolving at Pritchard Beach Wetland. As envisioned, the wetland habitats have become outdoor classrooms for neighborhood schools and community groups. A return visit to Pritchard Beach Wetland in a few years will hopefully reveal that these urban wetland habitats can resist the threat from invasive plants, flourish despite limited maintenance resources, and support a diversity of wildlife. |

||