|

|

|

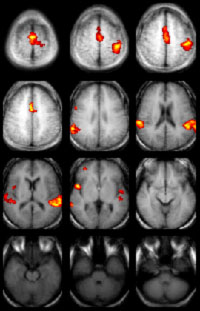

Deaf People Sense Vibrations in Auditory Cortex

|

|

|

|

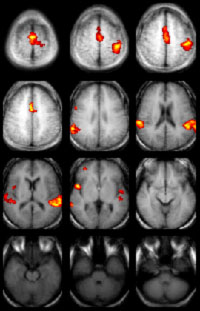

Bright colors show areas of brain activation in these functional magnetic resonance images.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Deaf people sense vibrations in their auditory cortex, a golf ball-sized area of the brain, active during auditory stimulation in hearing people. If sounds and musical vibrations are processed in the same part of the brain in deaf and hearing people, this may explain how deaf musicians can sense music, and how deaf people can enjoy concerts and other musical events.

“Vibrational information has essentially the same features as sound information. It makes sense that in the deaf, one modality may replace the other modality in the same processing area of the brain,” said Dr. Dean Shibata, assistant professor of radiology. “It’s the nature of the information, not the modality of the information, that seems to be important to the developing brain.”

Shibata used functional magnetic resonance imaging to compare brain activity between 10 deaf volunteers and 11 volunteers with normal hearing. They agreed to let Shibata scan their brains while subjected to intermittent vibrations on their hands. Both groups showed brain activity in the part of the brain that normally processes vibrations. In addition, the deaf participants showed brain activity in the superior temporal gyrus. This activity often extended into the anatomic regions of the secondary and sometimes primary auditory cortex. People with normal hearing did not usually show temporal lobe activity.

“It was once thought that brains were hard-wired at birth, and particular areas of the brain always did one function, no matter what else happened,” said Shibata. “It turns out that, fortunately, our genes do not directly dictate the wiring of our brains. Our genes do provide a developmental strategy: All the parts of the brain will be used to maximal efficiency.”

Shibata presented his findings at the 87th Scientific Assembly and Annual Meeting of the Radiological Society of North America in Chicago. He conducted this research while on the faculty at the University of Rochester School of Medicine in New York before joining the University of Washington in fall 2001.

|