July 30, 2021

Researchers share latest science at 2021 International AIDS Society Conference

Transitioning integrated antenatal PrEP delivery from research projects to routine clinic staff at 16 clinics in Western Kenya

F. Abuna1 , B. Odhiambo1 , N. Mwongeli1 , J. Dettinger2 , L. Gómez2 , J. Sila1 , M. Marwa1 , S. Watoyi1 , J. Pintye2 , J. Baeten2 , G. John-Stewart2 , J. Kinuthia1 , A. Wagner2 1 Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya, 2 University of Washington, Seattle, United States

Background: The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for pregnant and postpartum women at high risk for HIV acquisition. PrEP studies among Kenyan pregnant and postpartum women have found high PrEP acceptance within routine maternal and child health (MCH) settings. Transitioning demonstration projects from dedicated research teams to routine clinic staff not employed by studies is a common challenge in scale up and sustainability.

Methods: Following a cluster randomized trial (NCT03070600) comparing approaches for PrEP delivery to pregnant and postpartum women, we documented the active transition process from research teams to routine clinic staff. We utilized the WHO Health Systems Building Blocks Framework to actively transition care and qualitatively summarized the process through debrief checklists and matrices with study staff. Results: At 16 health facilities in Western Kenya that transitioned from research to routine clinic team delivery of antenatal PrEP in 2020-2021, all 16 successfully continued PrEP delivery for pregnant and postpartum women. The unique contexts at each clinic influenced heterogeneous solutions to how PrEP was successfully continued; at 6, PrEP delivery shifted to HIV care clinics, while at 10 PrEP remained integrated within MCH clinics. At all facilities, active transfer of medical commodities and tracking systems (PrEP medication, HIV testing kits, health records and registers) and transition of MCH PrEP users from research to routine health staff providers were successful with few noted challenges. Some facilities actively introduced MCH clients to HIV care clinics while others made a passive referral. Processes for ordering PrEP commodities were heterogeneous across facilities through existing procurement mechanisms, but were not impacted by departing study staff. Challenges arose around how existing health workforce absorbed new PrEP provision duties, adding to already overloaded responsibility lists. Many facilities identified a new PrEP point person to be mentored by departing research staff, typically the nurse in charge of preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV. At facilities with donor-supported HIV implementing partners (N=11), implementing partner staff generally assumed PrEP delivery roles.

Conclusions: Transitioning PrEP delivery from research to routine clinic teams was successful and yielded heterogeneous solutions to match local context. Health workforce burden remains a challenge.

Incidence and co-factors of Mtb infection in first 2 years of life: observational follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of INH to prevent primary Mtb infection among HIV-exposed uninfected children

S. LaCourse1 , J. Escudero1 , N. Carimo1 , B. Richardson1 , L. Cranmer2 , A. Warr3 , E. Maleche-Obimbo4 , J. Mecha5 , D. Matemo5 , J. Kinuthia5 , T. Hawn1 , G. John-Stewart1 , infant TB Prevention Study (iTIPS) 1 University of Washington, Seattle, United States, 2 Emory University, Atlanta, United States, 3 Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, United States, 4 University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 5 Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya

Background: In the infant TB Infection Prevention Study there was a trend for decreased TST-positivity after 12-months INH among Kenyan HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU) infants. We present 24-month observational follow-up.

Methods: Infants age 6 weeks without known TB exposure were randomized to 12-months INH vs. no INH. Mtb infection was measured at 12 months by interferon gamma release assay (IGRA, QFT-Plus), with tuberculin skin test (TST, positive ≥10 mm) added 6 months after first study exit due to low accrued endpoints. Follow-up was extended with repeat TST placed at 24 months. Observational outcome was cumulative Mtb infection by 24 months with any positive Mtb infection test considered ‘ever positive’. Correlates of Mtb infection were evaluated by generalized linear models and risk of conversions/reversions by multinomial regression.

Results: As previously reported, among 300 HEU infants enrolled (150/ arm), 28/265 (11%) with 12-month Mtb infection endpoints were positive, with a trend for lower 12-month Mtb infection among infants randomized to INH (HR 0.53 [95%CI 0.24-1.14], p=0.11]) driven by TST-positivity (RR 0.48 [95%CI 0.22-1.05], p=0.07). Among 228 children completing 24-month follow-up, 25 (13.3%) were TST-positive. Overall, 39/275 (14%) infants with Mtb infection outcome at 12 or 24 months were positive; cumulative Mtb infection incidence was 9.8/100 PY (INH 7.5 vs no INH 9.8/100 PY, HR 0.75 [95%CI 0.40-1.42], p=0.37] and associated with lack of flush toilet or r running water (p<0.001 and p=0.02, respectively). Among 162 infants with TST at 12 and 24 months, 68% (17/25) with 12-month TST-positivity reverted; 5.4% (7/137) TST-negative converted. While post-trial TST conversions were similar among no INH and INH (2/83 [2.4%] vs 5/79 [6.3%], RR 0.4 [95% CI 0.08-2.2], p=0.30), children not receiving INH were more likely to have TST reversions (No><0.001 and p=0.02, respectively). Among 162 infants with TST at 12 and 24 months, 68% (17/25) with 12-month TST-positivity reverted; 5.4% (7/137) TST-negative converted. While post-trial TST conversions were similar among no INH and INH (2/83 [2.4%] vs 5/79 [6.3%], RR 0.4 [95% CI 0.08-2.2], p=0.30), children not receiving INH were more likely to have TST reversions (No INH [13/83, 15.7%] vs. INH [4/79, 5.1%], RR 3.4 [95% CI 1.03-10.8], p=0.04).

Conclusions: In post-RCT follow-up, 24-month cumulative Mtb infection incidence measured primarily by TST was high and associated with poorer household conditions in this cohort of HEU children. Trend for decreased TST-positivity after 12 months of INH was not sustained. TST reversions occurred frequently; fewer reversions among INH recipients may reflect INH potential to delay the timing of primary infection.

A randomized trial of a standardized patient actor training intervention to improve adolescent engagement in HIV care in Kenya

P. Kohler1 , K. Wilson1 , C. Mugo2 , A. Onyango2 , B. Richardson1 , H. Moraa2 , I. Inwani2 , D. Bukusi2 , T. Owens3 , B. Guthrie1 , J. Slyker1 , G. John-Stewart1 , D. Wamalwa2 1 University of Washington, Seattle, United States, 2 University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 3 Howard University, Washington DC, United States

Background: Adolescents and young adults living with HIV (ALHIV) report that negative interactions with health care workers (HCWS) affected their willingness to return to care. We evaluated effectiveness of a standardized patient actor (SP) HCW training intervention on adolescent engagement in care.

Methods: We conducted a stepped wedge randomized trial of the SP intervention during 2016-2020. HCWs caring for ALHIV at 24 clinics in Kenya received training in adolescent care, values clarification, communication skills, and motivational interviewing, then rotated through seven SP encounters, followed by individual feedback and group debriefing. Facilities were randomized to four waves of timing of the intervention. The primary outcome, early engagement, was abstracted from electronic medical records and defined as return after first visit within 3 months among newly enrolled ALHIV, or ALHIV who returned after >3 months out of care. Generalized linear mixed models adjusted for time, newly enrolled, with clustering by facility calculated adjusted odds ratios (aORs).

Results: Overall, 139 HCWs were trained. HCWs reported significant improvement in competence in communication, empathy, clinical skills, and overall confidence comparing pre-and post-training (all p<0.001). Medical records were abstracted for 4,645 ALHIV with 45,422 visits. Most ALHIV (64%) were age 20-24, 25% were 15-19, and 11% were 10-14; 82% were female, 76% were newly enrolled in care, and 75% returned for care within 3 months of their first visit. Across all sites, ALHIV engagement significantly improved over time (global Wald test=0.05). In adjusted models, the intervention showed no significant effect on engagement [aOR=0.81, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 0.59-1.12]. There was high turnover of trained HCWs: 58% of wave 1 providers were in their position 9-months posttraining. Newly enrolled ALHIV had significantly higher engagement than those with prior lapses in care (aOR=1.80, 95%CI: 1.19-2.71). Conclusions: SP training resulted in higher confidence of HCWs providing ALHIV care. However, there was no statistically significant effect of SP training on ALHIV care engagement, likely due to high diffusion of the trained workforce and temporal improvements in engagement in care, reflecting program efforts. Strategies to retain SP-training benefits need to address HCW turnover. ALHIV with prior gaps in care may need more intensive support. ><0.001). Medical records were abstracted for 4,645 ALHIV with 45,422 visits. Most ALHIV (64%) were age 20-24, 25% were 15-19, and 11% were 10-14; 82% were female, 76% were newly enrolled in care, and 75% returned for care within 3 months of their first visit. Across all sites, ALHIV engagement significantly improved over time (global Wald test=0.05). In adjusted models, the intervention showed no significant effect on engagement [aOR=0.81, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 0.59-1.12]. There was high turnover of trained HCWs: 58% of wave 1 providers were in their position 9-months post training. Newly enrolled ALHIV had significantly higher engagement than those with prior lapses in care (aOR=1.80, 95%CI: 1.19-2.71).

Conclusions: SP training resulted in higher confidence of HCWs providing ALHIV care. However, there was no statistically significant effect of SP training on ALHIV care engagement, likely due to high diffusion of the trained workforce and temporal improvements in engagement in care, reflecting program efforts. Strategies to retain SP-training benefits need to address HCW turnover. ALHIV with prior gaps in care may need more intensive support.

No association between prenatal PrEP exposure and adverse growth outcomes among Kenyan infants: a prospective study

L. Gómez1 , J. Pintye1 , J. Stern1 , N. Ngumbau2 , B. Ochieng2 , M. Marwa2 , S. Watoyi2 , J. Dettinger1 , B. Richardson1 , F. Abuna2 , G. John-Stewart1 , J. Baeten1 , J. Kinuthia2 1 University of Washington, Seattle, United States, 2 Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya

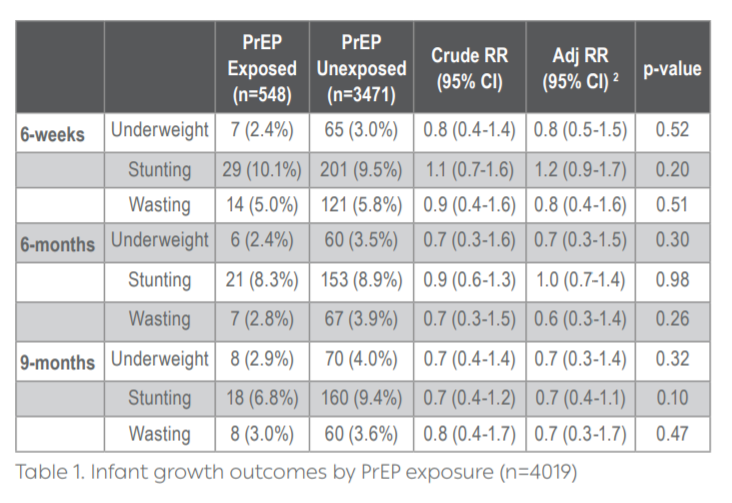

Background: The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends PrEP for pregnant women at-risk for HIV, yet calls for longer-term safety evaluations. We evaluated infant growth outcomes through 9 months following prenatal PrEP exposure.

Methods: Longitudinal data were analyzed from the PrEP Implementation for Mothers in Antenatal Care (PrIMA) study (NCT03070600). Women enrolled during pregnancy and infant anthropometry was conducted by trained nurses at 6-weeks, 6-months, and 9-months. WHO weight for-age, height-for-age, and weight-for-height z-scores were calculated; underweight, stunting, and wasting were defined as z-score<-2. This analysis included singleton pregnancies, with a live birth and documented gestational age. Women who initiated PrEP postpartum or HIV seroconverted were excluded. Infants with prenatal PrEP exposure were compared with PrEP-unexposed infants using multivariate GEE models, adjusting for gestational age, maternal syphilis, and age.

Results: In total, 4019 mother-infant pairs were analyzed (90% of total PrIMA participants). At enrollment, median maternal age was 24 years (IQR 21-28) and median gestational age was 24 weeks (IQR 20-30). Overall, 548 (13.6%) women used PrEP during pregnancy, initiating PrEP at a median of 26 weeks gestation (IQR 22-30); median duration of PrEP use during pregnancy was 11.9 weeks (IQR 7.1-17). Median weight was similar at 6-weeks (5.0 vs. 5.0 kg, p=0.80), 6-months (7.7 vs. 7.8 kg, p=0.04), and 9-months (8.6 vs. 8.6 kg, p=0.50) between groups. There were no differences in median infant length at 6-weeks (55.2 vs 55.0 cm, p=0.70), 6-months (66.0 vs. 66.0 cm, p=0.35), and 9-months (70.5 vs 70.0 cm, p=0.30). Prenatal PrEP exposure was not associated with underweight, stunting, or wasting at any timepoint (Table 1). Results were similar when analyzed separately by trimester of PrEP initiation.

Conclusions: In the largest safety study of PrEP in pregnancy to date, infant growth outcomes through 9 months did not differ by prenatal PrEP exposure.

Health systems-level barriers and strategies for improved PrEP delivery for pregnant and postpartum women in Western Kenya

A. Wagner1 , J. Dettinger1 , F. Abuna2 , B. Odhiambo2 , N. Mwongeli2 , L. Gómex1 , J. Sila2 , G. Oketch2 , E. Sifuna2 , J. Pintye1 , B.J Weiner1 , G. John-Stewart1 , J. Kinuthia2

1 University of Washington, Seattle, United States, 2 Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya

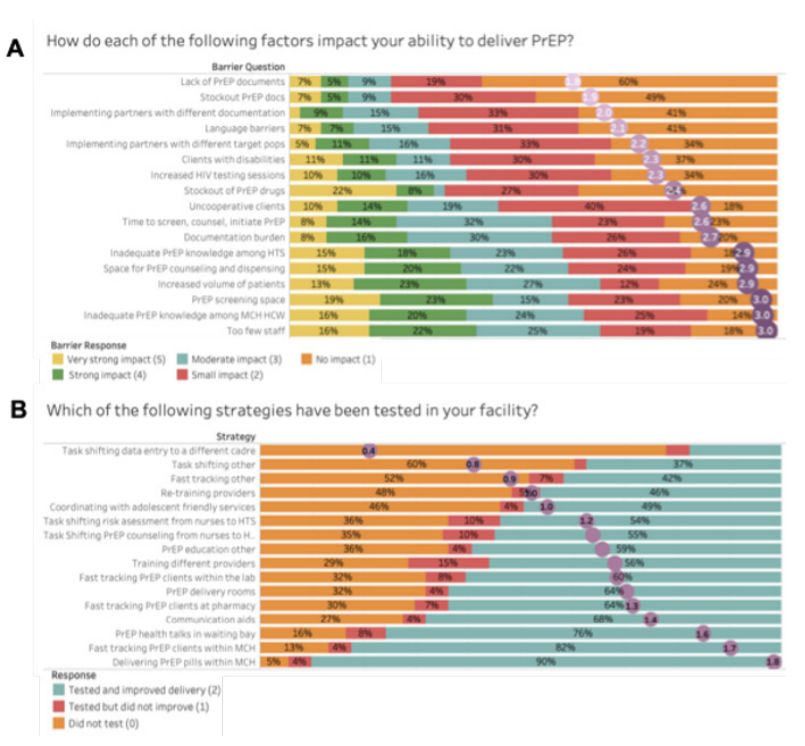

Background: Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is recommended for pregnant and postpartum women at high risk of HIV acquisition within maternal child health (MCH) systems. Identifying health system barriers to PrEP delivery and strategies to overcome barriers could optimize PrEP delivery within MCH systems.

Methods: We recruited health care workers (HCW) with experience delivering PrEP within MCH clinics in two large-scale projects in western Kenya (>25,000 MCH clients offered PrEP at 36 sites). Two surveys (a self-administered and a phone survey) were used to assess barriers to PrEP delivery and strategies to overcome barriers, based on previous qualitative work grounded in the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research.

Results: Among 101 HCW recruited, 91 completed the electronic survey and 88 the phone survey. Most (54%) were nurses, female (65%), had PrEP training specific to MCH (93%), and 4.3 years (IQR: 2.2, 6.5) providing PrEP. The strongest reported barriers to PrEP delivery were insufficient number of providers and inadequate training; increased volume of patients and time needed; insufficient physical PrEP services space; and documentation burden. Less impactful barriers included stockouts of PrEP drugs and documents; multiple implementing partners with competing priorities; increased HIV testing; and clients with challenges (Figure 1A). Strategies most frequently reported to have been tried and improved delivery included dispensing PrEP in MCH (90%); fast-tracking PrEP clients at MCH (82%), pharmacy (64%) or lab (60%); delivering PrEP education in waiting bays (76%) or other locations (59%); providing communication aids (68%); dedicating space for PrEP (64%); and task-shifting PrEP counseling (55%) and risk assessment (54%) from nurses to HIV testing services providers (Figure 1B).

Conclusions: Common barriers to service provision—including client-toprovider ratios, space, and documentation—hinder PrEP delivery. Strategies for co-location, fast-tracking, training, and task-shifting are useful for integrating PrEP provision within MCH care.

Influences on healthcare worker acceptability, feasibility and sustainability of an Adolescent Transition Package in Kenya

D. Mangale1 , I. Njuguna1 , C. Mugo1 , A. Price1 , C. Mburu1 , H. Moraa1 , J. Itindi2 , D. Wamalwa2 , G. John-Stewart1 , K. Beima-Sofie1

1 University of Washington, Global Health, Seattle, United States, 2 Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya

Background: Successfully preparing and transitioning adolescents living with HIV (ALHIV) from pediatric to adult care is critical for ensuring adherence and retention in care. We developed and implemented an Adolescent Transition Package (ATP), which combines HIV disclosure and transition tools, in 10 clinics in Kenya as part of a cluster randomized clinical trial. Understanding healthcare worker (HCW) experiences with implementation of the ATP can identify influences on acceptability and feasibility that inform future scale-up and scale out of the ATP intervention.

Methods: Guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), we conducted 10 semi-structured focus group discussions (FGDs) (one per clinic) with 76 HCWs to evaluate factors influencing ATP implementation. FGDs were recorded and transcribed verbatim. An analysis of FGD debrief reports and a subset of full transcripts was conducted to identify key influences on implementation.

Results: HCWs believed the ATP intervention was acceptable, feasible and improved the transition process for HCWs and ALHIV. HCWs described how ATP tools met the needs of adolescents, and resulted in improved viral suppression, ART adherence, and retention. The ATP provided a relative advantage when compared to existing tools because it was 1) systematic and provided a step-by-step guide, 2) simple and easy for any provider, including peer educators, to use, and 3) comprehensive, covering both medical and psychological components. The Taking Charge booklet was the most valuable component, providing relevant content in multiple languages and including well-liked illustrations. Feasibility and acceptability were enhanced through systematic study-facilitated adaptations including designated roles for staff and group delivery of book chapters, through which HCWs optimized delivery within their clinic. Flexibility in ATP tools enabled HCWs to expand use to include adolescents and pregnant women outside the study. This underscores broad acceptability and potential for scalability of the intervention. While HCWs were enthusiastic about continuing and scaling implementation post-trial, barriers to perceived sustainability included HCW time and workload.

Conclusions: The ATP intervention improved HCW experiences with preparing ALHIV to transition to adult care. Strategies that support intervention scale-up should address identified barriers to implementation, and incorporate new ways to enhance ATP reach and versatility.

Risk factors for adverse birth outcomes among women living with HIV on ART in pregnancy

W. Jiang1 , L. Osborn2 , A. L. Drake1 , J. A. Unger1 , D. Matemo2 , J. Kinuthia2 , K. Ronen1 , G. John-Stewart1

1 University of Washington, Seattle, United States, 2 Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya

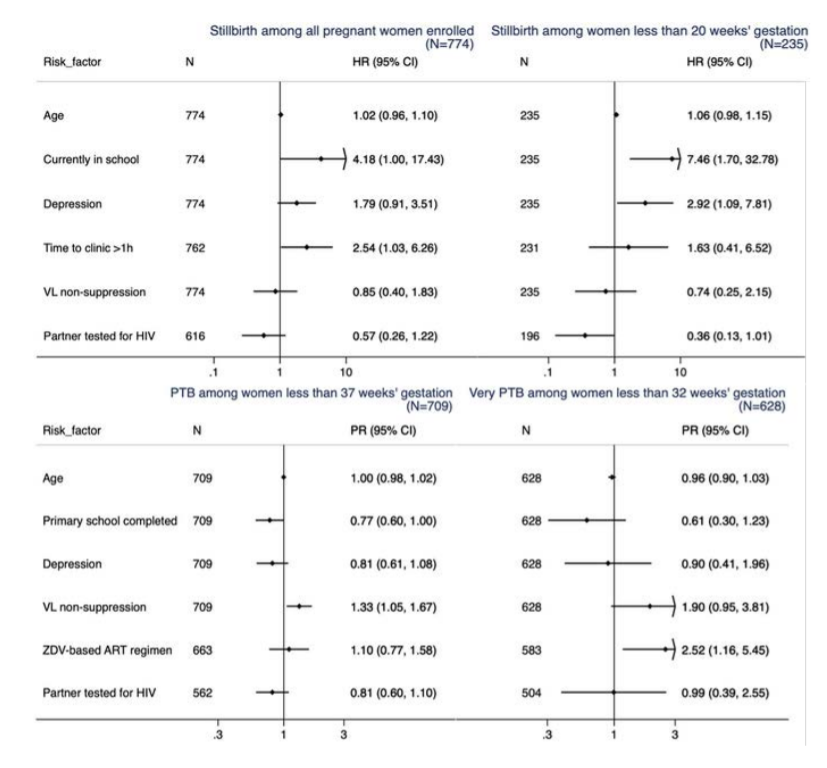

Background: It is important to understand predictors of adverse birth outcomes among women living with HIV on antiretroviral treatment (ART) to optimize prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) care.

Methods: This study evaluated adverse birth outcomes including stillbirth (fetal death at ≥20 weeks’ gestation), preterm birth (PTB, livebirth at ≤37 weeks; very PTB at ≤32 weeks) and neonatal death (≤28 days after birth), using data from a randomized clinical trial (NCT02400671). Gestational age was determined by last menstrual period. Women with miscarriage were excluded. Potential correlates were determined by site adjusted Cox PH models and log-binomial models. Results: Among 774 pregnant women at enrollment, median age was 27 years, median gestational age was 24 weeks (IQR 18-30), and 226 (29.0%) were virally unsuppressed (VL ≥1000 copies/mL). Half of women (55.1%) started ART pre-pregnancy. Most (89.1%) received tenofovir (TDF) with the remainder on zidovudine (ZDV)-based regimens. During 211.5 person-years of follow-up until delivery, 34 women had stillbirth (incidence rate 16.1 per 100 person-years). Stillbirth was associated with being in school and living >1 hour from clinic. Among women enrolled at <20 weeks’ gestation, those whose partner tested for HIV had lower risk (HR 0.36; p=0.05) and those with depression (PHQ9>5) had higher risk (HR 2.92; p=0.03). Among 740 live births, 201 (27.2%) were PTB (31 vPTB) and 22 (3.0%) neonatal deaths occurred. PTB was associated with unsuppressed VL in pregnancy (PR 1.33; p=0.02) and non-completion of primary school (PR 1.30; p=0.05). vPTB was more frequent with ZDV- than TDF-based ART (12.9% vs. 4.4%, p=0.005). Neonatal death was associated with PTB (PR 2.46, 95%CI 1.10-5.51; p=0.03).

Conclusions: PTB risk was substantial and associated with VL non-suppression, ART regimen and neonatal death. Pre-pregnancy ART may decrease HIV transmission and PTB; underlying regimen-effects should be explored. Supporting education, depression counseling and partner involvement may help prevent adverse birth outcomes.