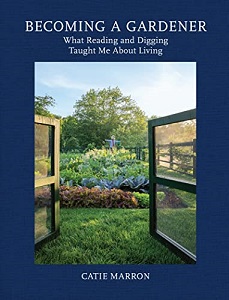

First off, this book is a feast for the eyes. Big glossy photographs of Marron’s garden are combined with charming gouaches from the Copenhagen collective studio All the Way to Paris, plus an array of painting reproductions ranging from Beatrix Potter to Cy Twombly. The visual experience is rich.

Marron, with a background of success in business and journalism, assigned herself the task of learning to garden in eighteen months. She and her husband had bought a house in Connecticut, but she needed to put down literal as well as figurative roots to feel she belonged to this land. This book is an account of that journey.

An impressive amount of gardening research preceded and intertwined with the development of the garden itself. Marron includes memories of gardens in children’s books like “The Secret Garden” and the visit to the Luxembourg Garden in “Madeline.” As she read classic gardening books, she learned there are many kinds of gardeners, and they all have strong opinions, often differing with each other. From Alexander Pope’s idea of a “spirit of the place” she learned that she wanted her garden to echo its own surroundings. And after reading about famed gardens and recalling those she had visited, she realized she had to build something smaller and simpler than any of them.

In her learning process, Marron watched carefully to see how even cut flowers changed over a few days. She put aside her conviction that she did not have a green thumb and sought out hands-on mentors, who taught her what to do and that persistence and hard work can lead to gardening success for anyone. With a landscape architect she developed a plan and turned a 48 x 54-foot space into a walled garden.

One notable discovery from her research was that gardeners make mistakes, learn to accept them, and start over. She describes several of those she made, seeing them as part of the learning process.

In the section on “Building My Garden” Marron describes working to create a garden that fit her goal of relative simplicity and comfort in its surroundings. She struggled with fencing, replacing one design that turned out to look like “a corral fence from the Wild West” with a more pleasing one. She developed a layout with rectangular beds and wide paths. She spent many hours choosing flowers and vegetables and then deciding where to plant them. She considered color and scent, even choosing to paint cold frames “a happy yellow” and the door frames of the garage bay “bright grass green,” the same green Monet used for his own door and window frames.

In the middle of the project Marron’s husband died. Grieving, she came to learn how digging in the dirt can help heal pain. She describes five kinds of gardeners: “scene setters, plantspeople, colorists, collectors, and dirt gardeners” (p. 78). Dirt gardening was her choice. As she returned to dig in the garden after her loss, she felt connected to soil and roots.

At the back of the book Marron includes a list of “Literary Mentors in the Garden,” with a paragraph about each. A page of “Recommended Reading and Viewing” and a very thorough bibliography provide further research opportunities for those who aspire to the title of “gardener.” For herself, Marron still considers herself an “urban dweller,” but she attests to the power of her gardening project to make a major difference in her life.

Reviewed by Priscilla Grundy for The Leaflet, Volume 9, Issue 12 (December 2022).