The Miller Library receives many donations of books each year, and sometimes we open a box and a particular book enchants us. A recent example is a small volume entitled Wild Flowers of the Undercliff, Isle of Wight, published in London in 1881. It is a field guide to a small area of the southern coast of the Isle of Wight, England. The region is prone to landslides and possesses a unique microclimate, as it is protected beneath an escarpment, facing south. The authors, Charlotte O’Brien and C. Parkinson, hoped the book would enable temporary residents of the Undercliff to acquaint themselves with the various plants blooming throughout the year. “As a rule, they are very timid, these ‘wildings of Nature,’ and recede before the advances of man and his bricks and mortar,” and this book seeks to help “seekers after one of the purest of earthly pleasures” [wildflowers] find them.

The Miller Library receives many donations of books each year, and sometimes we open a box and a particular book enchants us. A recent example is a small volume entitled Wild Flowers of the Undercliff, Isle of Wight, published in London in 1881. It is a field guide to a small area of the southern coast of the Isle of Wight, England. The region is prone to landslides and possesses a unique microclimate, as it is protected beneath an escarpment, facing south. The authors, Charlotte O’Brien and C. Parkinson, hoped the book would enable temporary residents of the Undercliff to acquaint themselves with the various plants blooming throughout the year. “As a rule, they are very timid, these ‘wildings of Nature,’ and recede before the advances of man and his bricks and mortar,” and this book seeks to help “seekers after one of the purest of earthly pleasures” [wildflowers] find them.

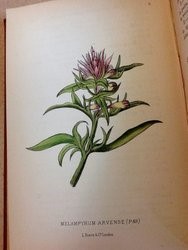

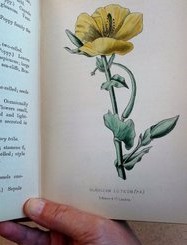

As a librarian, I have absorbed a concern for ‘bibliographic control,’ the attention to details that help people find the information they need. I was troubled by the lack of a first name for the co-author, and curious about the note in the preface in which the two authors thank “Miss Parkinson” for her colored drawings [8 plates] that illustrate the book. Our copy of the book was inscribed by M. Parkinson, with a dedication to “Miss Prince.” Who were these nameless Parkinsons, I wondered, wanting to give bibliographic credit where it was due.

I asked assistance from a friend who is a gardener and genealogist in England, and she found a reference to an article by David E. Allen (affiliated with the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland), “C. Parkinson, A mystery Wight Botanist identified,” which was published in the 2009 proceedings of the Isle of Wight Natural History & Archaeological Society. We could not obtain a copy, and that made both of us even more eager to solve the mystery.

The initials F.G.S. after Parkinson’s name on the book’s title page might stand for ‘Fellow of the Geological Society,’ and that led to a discovery of an obituary for a “Cyril Parkinson” in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London Vol 26 (1920): “Cyril Parkinson was born at Hesgreave [Hexgreave] Park, near Southwell (Nottinghamshire), and died in London on August 20th, 1919, at the age of 65. During five years’ residence in the Isle of Wight (1875-¬80) he made a collection of fossils, which was acquired by the British Museum (Natural History). He became a Fellow of our Society in 1880. He was a member of the Worcester Naturalists’ Club, and an occasional contributor to ‘Borrow’s [Berrow’s] Worcester Journal’ on natural history subjects. He also contributed articles to various periodicals on natural history, geology, and botany, and brought out a handbook of the Isle of Wight Marine Algae in collaboration with Mrs. O’Brien, of Ventnor.”

Now that I had birth and death dates and a first name, I used genealogy resources like Ancestry.com and found that Cyril had a sister Marian who lived with him for a time, and she was undoubtedly the illustrator whose signature is in our copy. Census records indicate that she was a woman of “private means,” and this squares with the family’s history as landed gentry with their own coat of arms. At the time of the book’s publication, the 1881 census lists Cyril as a tile manufacturer living with his unmarried sister Marian in Bournemouth, not terribly distant from the Isle of Wight. Their parents were John and Catherine Parkinson of Southwell, Nottinghamshire.

Now that I had birth and death dates and a first name, I used genealogy resources like Ancestry.com and found that Cyril had a sister Marian who lived with him for a time, and she was undoubtedly the illustrator whose signature is in our copy. Census records indicate that she was a woman of “private means,” and this squares with the family’s history as landed gentry with their own coat of arms. At the time of the book’s publication, the 1881 census lists Cyril as a tile manufacturer living with his unmarried sister Marian in Bournemouth, not terribly distant from the Isle of Wight. Their parents were John and Catherine Parkinson of Southwell, Nottinghamshire.

A review of Wild Flowers of the Undercliff appeared in the October 11, 1901 edition of The British Architect and it makes special note of the illustrations: “There are eleven different species of the orchid tribe growing in the Undercliff, and this guide helps one to find these ‘wildings of Nature.’ The beautiful coloured drawings were executed by Miss Parkinson.”

It is very satisfying to list the full names of the co-author and illustrator in the bibliographic record for this book. I would love to discover whether Marian Parkinson illustrated any other botany books, but that is still a mystery.

The UW Farm is a great example of the increasing interest in urban agriculture, but this is not a new movement.

The UW Farm is a great example of the increasing interest in urban agriculture, but this is not a new movement.

New on our shelves this month you’ll find Richard Louv’s new book,

New on our shelves this month you’ll find Richard Louv’s new book,