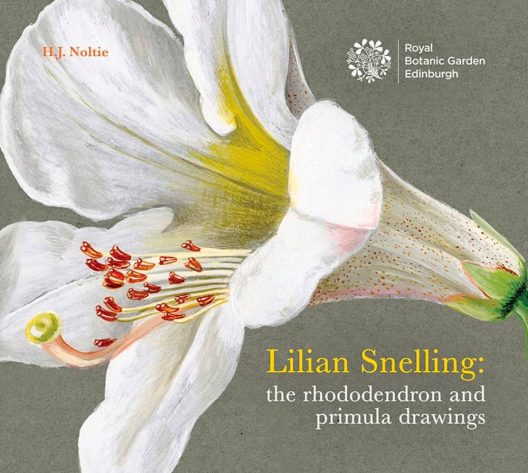

“Lilian Snelling (1879-1972) was probably the most important British botanical artist of the first half of the 20th century.” This bold statement was made by Brent Elliott, the long-standing Head Librarian and Historian for the Royal Horticultural Society, in an article for that society’s journal “The Garden” in July 2003.

This is especially surprising as very little is known about her until at the age of 36, she became the protégé of Henry John Elwes, a well-known English botanist and dendrologist, using her skills to draw plants from his extensive garden. At his recommendation, she spent five years at the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, honing her skills. Her precise work from that time is the basis for the 2020 book “Lilian Snelling: the Rhododendron and Primula Drawings” by Henry J. Noltie.

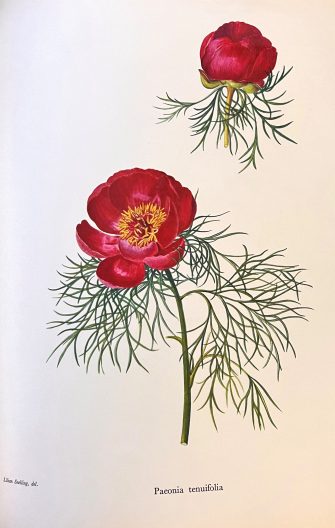

Snelling’s illustrations can also be found in the monograph on the genus Lilium by Elwes. Although the Miller Library does not have this book, her illustrations have been reproduced in other books on lilies in the collection. She also produced the exquisite color plates and drawings for “A Study of the Genus Paeonia” by Frederick Claude Stern (1946), including this illustration of Paeonia tenuifolia.

Snelling’s illustrations can also be found in the monograph on the genus Lilium by Elwes. Although the Miller Library does not have this book, her illustrations have been reproduced in other books on lilies in the collection. She also produced the exquisite color plates and drawings for “A Study of the Genus Paeonia” by Frederick Claude Stern (1946), including this illustration of Paeonia tenuifolia.

Snelling was appointed as an artist for “Curtis’s Botanical Magazine” and for 30 years was the principal artist. She also was a skilled lithographer, being able to transfer her work and those of others to zinc plates for reproduction. Upon her retirement, the November 1952 volume of “Curtis’s” was dedicated to her. The dedication describes how she “with remarkable delicacy of accurate outlines, brilliancy of colour, and intricate gradation of tone has faithfully portrayed most of the plants figured in this magazine from 1922 to 1952.”

Reviewed by: Brian Thompson on November 21, 2023

Excerpted from the Winter 2024 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

“Lilian Snelling (1879-1972) was probably the most important British botanical artist of the first half of the 20th century.” This bold statement was made by Brent Elliott, the long-standing Head Librarian and Historian for the Royal Horticultural Society, in an article for that society’s journal “

“Lilian Snelling (1879-1972) was probably the most important British botanical artist of the first half of the 20th century.” This bold statement was made by Brent Elliott, the long-standing Head Librarian and Historian for the Royal Horticultural Society, in an article for that society’s journal “ .

. The Panakanic Prairie is a vernally moist meadow amongst the coniferous forests north of White Salmon, Washington that turns blue each May with the flowers of camas (Camassia quamash). It has a rich human history, including that of the Klickitat people. From the 1880s through much of the 20th century, it was the home and ranch of the Markgraf family.

The Panakanic Prairie is a vernally moist meadow amongst the coniferous forests north of White Salmon, Washington that turns blue each May with the flowers of camas (Camassia quamash). It has a rich human history, including that of the Klickitat people. From the 1880s through much of the 20th century, it was the home and ranch of the Markgraf family. Molly Hashimoto is a good friend of the Miller Library, having exhibited in our space for many years, typically each November and December. Her books are a blend of engaging watercolors and block prints, while the text educates the reader about both art techniques and the subjects of the illustrations.

Molly Hashimoto is a good friend of the Miller Library, having exhibited in our space for many years, typically each November and December. Her books are a blend of engaging watercolors and block prints, while the text educates the reader about both art techniques and the subjects of the illustrations. After an especially difficult period in her life, Seattle gardener, author, and artist Lorene Edwards Forkner began a daily, meditative practice. She would pick something from her garden and using watercolors, paint a 3×3 pattern of distinct color squares, trying to capture each of the colors she saw in the subject.

After an especially difficult period in her life, Seattle gardener, author, and artist Lorene Edwards Forkner began a daily, meditative practice. She would pick something from her garden and using watercolors, paint a 3×3 pattern of distinct color squares, trying to capture each of the colors she saw in the subject. encouragement, Seattle author and artist Suzanne Brooker begins “Essential Techniques of Landscape Drawing.”

encouragement, Seattle author and artist Suzanne Brooker begins “Essential Techniques of Landscape Drawing.” Francisca Darts (1916-2012) had a wide range of interests. Born in the Netherlands, she loved winter sports, including skating and curling. The latter she learned at age nine when her family moved to Canada. She bred and raised Shetland sheepdogs, enjoyed traveling, and was an avid reader and buyer of books. She and her husband Ed Darts (1903-1994) were early adopters of a home audio system to listen to their large collection of classical and big band records.

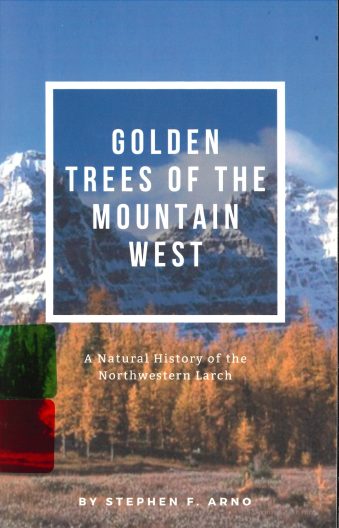

Francisca Darts (1916-2012) had a wide range of interests. Born in the Netherlands, she loved winter sports, including skating and curling. The latter she learned at age nine when her family moved to Canada. She bred and raised Shetland sheepdogs, enjoyed traveling, and was an avid reader and buyer of books. She and her husband Ed Darts (1903-1994) were early adopters of a home audio system to listen to their large collection of classical and big band records. Stephen Arno has been writing about Pacific Northwest trees since the 1970s. In 2021, he published “Golden Trees of the Mountain West,” a profile of the two species of larch found in the Pacific Northwest, Larix occidentalis, the western larch, and L. lyallii, the alpine larch. Unlike most conifers, these species are deciduous and achieve glorious fall color in shades of gold. I have been in the Cascades during October and marveled at the bright yellow, almost chartreuse, of the western Larch, standing in contrast to the surrounding dark greens of other conifers.

Stephen Arno has been writing about Pacific Northwest trees since the 1970s. In 2021, he published “Golden Trees of the Mountain West,” a profile of the two species of larch found in the Pacific Northwest, Larix occidentalis, the western larch, and L. lyallii, the alpine larch. Unlike most conifers, these species are deciduous and achieve glorious fall color in shades of gold. I have been in the Cascades during October and marveled at the bright yellow, almost chartreuse, of the western Larch, standing in contrast to the surrounding dark greens of other conifers.