In the 1720s, the 3rd Earl of Burlington planted orange trees at Chiswick House to show his unhappiness with the current Whig Party. Orange trees were associated with William of Orange, whose accession to the English throne in 1689 had been engineered by the Whigs Burlington favored. Politics in the garden. Think of a Republican now placing a statue of Eisenhower in her garden to show she liked Republicans from that era as opposed to the present party.

Later in the century political elements disappear from these gardens. Richardson shows the changes in garden design from an easing of formality in the first part of the century to the even less formal designs of Lancelot Brown in midcentury to the curated wildness of the Picturesque style at the end.

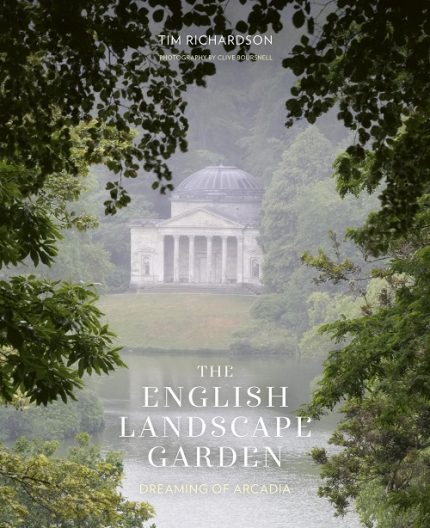

A landscape garden includes “episodes,” various areas with a particular focus, often a statue or a structure such as a temple or hermitage. Our current concept of garden may be stretched by knowing that dozens of buildings were integral to the design of some of these gardens.

Part of the change of design over the years was from an episode that was intended to be experienced for itself to, in the picturesque era, a location framed so one could look out to a distant vista or a nearby “natural” scene such as a carefully engineered waterfall.

Juicy biographical tidbits about the owners of these gardens add to the flavor. John Aislabie, for instance, turned his attention to developing Studley Royal, his marvelous Yorkshire garden, only after he was disgraced for financial shenanigans leading to the South Sea Bubble in 1720, which caused an international financial crisis.