I received at an early age a birthday present of a dozen gladiolus corms. The results – plants taller than I was, with brilliant colors – were enthralling and made me a life-long bulb (more accurately: geophyte) enthusiast. For author Chris Wiesinger, it started with a single red tulip bulb. He planted “his little rock” in his Central Valley of California home and forgot it. The next spring “something magical had occurred; my living rock had turned into the most striking red tulip.”

I received at an early age a birthday present of a dozen gladiolus corms. The results – plants taller than I was, with brilliant colors – were enthralling and made me a life-long bulb (more accurately: geophyte) enthusiast. For author Chris Wiesinger, it started with a single red tulip bulb. He planted “his little rock” in his Central Valley of California home and forgot it. The next spring “something magical had occurred; my living rock had turned into the most striking red tulip.”

Sadly, this was a one-and-done experience. The next year, only leaves appeared. A year later, he dug down to find the remains of a rotted bulb. But it lit a spark, and for Wiesinger, this experience turned into a combination business and consuming passion. He wrote his story in “The Bulb Hunter,” co-written with William Welch.

Wiesinger was only a temporary Californian. He returned to his southern roots in Louisiana and now Texas, searching for bulbs who have long out-survived the demise of the house they surrounded. This includes an elusive, perennial red tulip (Tulipa praecox), but it is found only where there is gritty black clay, so hard that it bends shovels. This quality protects the bulbs from their natural enemies, gophers and voles, and the good drainage allows drying out in the summer, much like the tulip’s central Asian homelands.

The book is divided into two halves, with the second being author Welch’s story. His is more typical garden memoir, recounting the bulbs and companion plants that thrive in each season for Texas and the Gulf South. While it is a stretch to use this as guidance for Pacific Northwest gardening, there are some interesting possibilities here, and I’m looking forward to trying them.

I was pleased that gladiolus species are prominent in both halves of the book. Gladiolus byzantinus (syn. G. communis var. byzantinus) is found in old cottage style gardens and Wiesinger considers it one of the most valuable bulbs he sells. Unfortunately, it is also a favorite of gophers and voles. The challenges of thwarting these “glad lovers” will amuse every gardener.

Excerpted from the Fall 2019 Arboretum Bulletin.

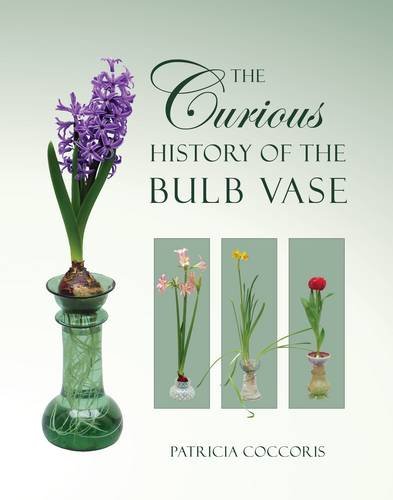

Bulb season is upon us—time to consider forcing a few for winter indoor color. Amongst the many bulb books in the Miller Library are a handful that focus on this delightful art.

Bulb season is upon us—time to consider forcing a few for winter indoor color. Amongst the many bulb books in the Miller Library are a handful that focus on this delightful art.