It’s hard to imagine a more botanical novel than Katy Simpson-Smith’s The Weeds, which takes its narrative structure from Richard Deakin’s 1855 book Flora of the Colosseum of Rome, or, Illustrations and Descriptions of Four Hundred and Twenty Plants Growing Spontaneously upon the Ruins of the Colosseum of Rome. The primary characters are two intentionally unnamed women, one in 2018 and the other in 1854, and the occasional refrain of a ghost, the unsettled spirit of Richard Deakin hovering over the Colosseum.

The contemporary woman is a graduate student from Mississippi, gathering plant observations for her thesis advisor. She is a keen observer of plants and people, and we soon learn she has recently lost her mother (who also had a strong connection with plants). As she works on the Rome Colosseum project, she develops an idea for a thesis exploring climate change through the plant life in Jackson’s Mississippi Coliseum. The 19th century woman has transgressed the norms of society: she is eager to avoid an arranged marriage and takes up petty thievery to make herself unmarriageable. The “you” addressed in her narrative is her lover, a woman. She works as Deakin’s indentured assistant, observing and describing the plants.

Both women consider the wild plants in context (how are they used by humans and animals, how they fit in an ecosystem, how climate affects them). For this, both are rebuked. The thesis advisor is dismissive, telling his student she has “an anecdotal mind,” whereas true scientists (men) are rational, and do not allow sentiment to intrude. Her role is to record and learn, his role is to interpret and author. The fictional Deakin tells his assistant that science is knowledge freed from emotion, and she wonders “how many days or centuries it will take for him to be proven wrong.” Whenever either woman mentions mystical, medical, or agricultural associations of the plants, they are told these things are irrelevant. But the 19th century woman believes “there is a bias against time here, and I must fault science for its disregard of history. Does it think knowledge is not accumulated but sudden?”

By turns furious, hilarious, and botanically erudite, this deeply feminist novel shines a light on the relative invisibility of women’s contributions to botany in particular and science in general. The women characters are never named because that has so often been the case in real life. Nothing in the historical record suggests a resemblance between the fictional Richard Deakin and the real one, but there are undoubtedly many instances of women overlooked and omitted as co-authors and researchers, whose contributions to the pool of knowledge remain unrecognized. Their absence from the record is a ghost that should haunt us.

The book includes a dozen exquisite graphite drawings by Kathy Schermer-Gramm, depicting selected plants of the character’s proposed Flora Colisea Mississippiana. If you want to explore Deakin’s book, a digitized copy is linked here and in the catalog record.

Reviewed by Rebecca Alexander, published in the Leaflet for Scholars, Volume 10, Issue 10, October 2023.

John Evelyn (1620-1706) was one of the great diarists of 17th century England. His observations written over 65 years give historians keen insights to turbulent times that included a civil war, the execution of a king (Charles I), an outbreak of plague, and the Great Fire of London.

John Evelyn (1620-1706) was one of the great diarists of 17th century England. His observations written over 65 years give historians keen insights to turbulent times that included a civil war, the execution of a king (Charles I), an outbreak of plague, and the Great Fire of London. John Evelyn (1620-1706) was one of the great diarists of 17th century England. His observations written over 65 years give historians keen insights to turbulent times that included a civil war, the execution of a king (Charles I), an outbreak of plague, and the Great Fire of London.

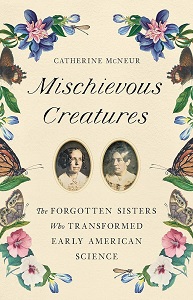

John Evelyn (1620-1706) was one of the great diarists of 17th century England. His observations written over 65 years give historians keen insights to turbulent times that included a civil war, the execution of a king (Charles I), an outbreak of plague, and the Great Fire of London. When I was very small, my mother often called me “Little Miss Mischief.” It meant I had once again done something wrong, but not terribly wrong, and maybe a little bit cute. I was happy with the title. Elizabeth and Margaretta Morris, the sisters of the title of Catherine McNeur’s book, were not so fortunate. Their mischief was seen as serious; they were challenging the exclusive male 19th century science establishment as they sought opportunity and recognition for their work.

When I was very small, my mother often called me “Little Miss Mischief.” It meant I had once again done something wrong, but not terribly wrong, and maybe a little bit cute. I was happy with the title. Elizabeth and Margaretta Morris, the sisters of the title of Catherine McNeur’s book, were not so fortunate. Their mischief was seen as serious; they were challenging the exclusive male 19th century science establishment as they sought opportunity and recognition for their work.

In

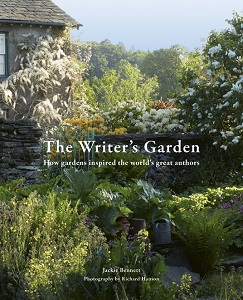

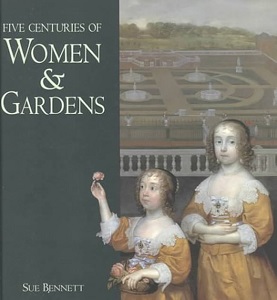

In  The National Portrait Gallery in London reopened this June after three years of closure due to Covid (and refurbishing). To celebrate, readers can pick up this excellent book from 2000, written to support an exhibition at the Gallery.

The National Portrait Gallery in London reopened this June after three years of closure due to Covid (and refurbishing). To celebrate, readers can pick up this excellent book from 2000, written to support an exhibition at the Gallery. Today raft trips through the Grand Canyon are common. Several companies offer choices of a few or many days. One specifies that the client must be at least nine years old. These trips differ greatly from the one Elzada Clover and Lois Jotter took in 1938. One difference is the Hoover Dam. Before the dam, the Colorado River challenged travelers with extreme rapids, rapids now slowed and sometimes covered by the water that rose behind the dam.

Today raft trips through the Grand Canyon are common. Several companies offer choices of a few or many days. One specifies that the client must be at least nine years old. These trips differ greatly from the one Elzada Clover and Lois Jotter took in 1938. One difference is the Hoover Dam. Before the dam, the Colorado River challenged travelers with extreme rapids, rapids now slowed and sometimes covered by the water that rose behind the dam.

The National Herbarium of New South Wales, Australia, acts as setting and springboard for Prudence Gibson’s narratives about and descriptions of preserved plants. Gibson holds in admirable tension the wonders of the herbarium and the troubling colonialism that assumed authority over Australia’s plants, collecting them without permission, naming and organizing them by European standards. The question of who owns plants hovers in the background.

The National Herbarium of New South Wales, Australia, acts as setting and springboard for Prudence Gibson’s narratives about and descriptions of preserved plants. Gibson holds in admirable tension the wonders of the herbarium and the troubling colonialism that assumed authority over Australia’s plants, collecting them without permission, naming and organizing them by European standards. The question of who owns plants hovers in the background.