For several of her teenage years in Ireland, Diana Beresford-Kroeger lived in fear of being sent by the government to one of the infamous Magdalene Laundries, where orphans like her and unwed mothers suffered abuse and maltreatment . Her second parent died when she was thirteen, and at first it seemed no one would care for her. Then Uncle Pat relented, leading to wonderful summers in the Irish countryside.

. Her second parent died when she was thirteen, and at first it seemed no one would care for her. Then Uncle Pat relented, leading to wonderful summers in the Irish countryside.

Numerous aged women there chose her as a vessel to receive beliefs, stories, and especially ways of healing, that went back to the Druids. Much of this knowledge had been hidden from the ruling British during what the author calls the penal period. In the process, Beresford-Kroeger learned to affirm herself after her traumatic childhood, and to love and honor nature, especially trees.

Beresford-Kroeger writes winningly about this period of her life. Especially given that her parents had not paid much attention to her when they were alive, she makes clear how much these women were responsible for enabling her to develop into the respected scientist and author she became.

After college in Ireland, Beresford-Kroeger came first to the U.S. for a few years, and then settled in Canada. There she completed at Ph.D. but opted out of an academic career after experiencing much discrimination because she was a woman. Instead, she found success as an independent scholar, though she says she fears the word “success” as associated with greed.

The first 186 pages of this 284-page book tell the above story. It brings together her own amazing history, her botanist’s outlook, and the often mystical understanding of the Druids. The final section is a Celtic alphabet of trees. The Celts assigned trees’ names to each letter of their Ogham alphabet. For example, the letter H was called “Huath,” and the tree is the hawthorn. A drawing of each letter is included, plus a description of the letter:” H is designated as a vertical line met by a single horizontal line to the left” (p. 227).

Along with each letter, Beresford-Kroeger gives information about the tree, the healing properties assigned to it by the Celts, and often, how modern scientists have discovered its medicinal value – sometimes the same as the Celts’, sometimes different. The ancients used extracts from hawthorns for “unspecified weakness.” Today medicines developed from that tree are used for hypertension associated with various heart problems.

Two of Beresford-Kroeger’s previous books – Arboretum America and The Global Forest – are also available at the Miller Library. This one adds background and context to them. About a year after her parents died, she remembers standing outside one of those Magdalene Laundries and smelling fear. This book shows how she channeled that fear into a powerful advocacy.

Published in the Leaflet, June 2022, Volume 9, Issue 6.

“Arboretum” is a new book this spring in the “Welcome to the Museum” series from Big Picture Press. The Miller Library has three titles in this series, all illustrated by Katie Scott, collaborating with different text authors.

“Arboretum” is a new book this spring in the “Welcome to the Museum” series from Big Picture Press. The Miller Library has three titles in this series, all illustrated by Katie Scott, collaborating with different text authors. In the preface of

In the preface of  Read this book to have fun with tales, myths, legends, and historical facts about British trees. Mark Hooper says the book aims “to explore the space where social history meets natural history” (p. 9). Along the way he ties events familiar and unfamiliar to many individual trees.

Read this book to have fun with tales, myths, legends, and historical facts about British trees. Mark Hooper says the book aims “to explore the space where social history meets natural history” (p. 9). Along the way he ties events familiar and unfamiliar to many individual trees. . Her second parent died when she was thirteen, and at first it seemed no one would care for her. Then Uncle Pat relented, leading to wonderful summers in the Irish countryside.

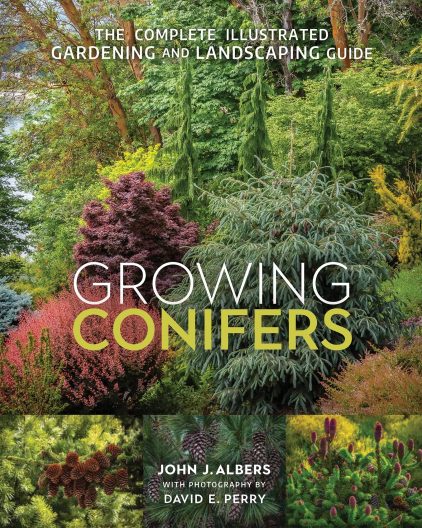

. Her second parent died when she was thirteen, and at first it seemed no one would care for her. Then Uncle Pat relented, leading to wonderful summers in the Irish countryside. John Albers has highlighted his garden of 20 years in Bremerton and his passion for sustainable gardening practices in two previous books. Now, he turns his attention to a favorite plant group: conifers, especially dwarf and small cultivars. He is very clear in his reasons for writing the book. “Given the horticultural and ecological importance of urban conifers, it is vital that all of us do our part to restore conifers to our urban environment.”

John Albers has highlighted his garden of 20 years in Bremerton and his passion for sustainable gardening practices in two previous books. Now, he turns his attention to a favorite plant group: conifers, especially dwarf and small cultivars. He is very clear in his reasons for writing the book. “Given the horticultural and ecological importance of urban conifers, it is vital that all of us do our part to restore conifers to our urban environment.”