|

|

|

|

The Christian Basilica |

|

written

by leahs2 / 09.29.2005 |

|

|

| |

Introduction |

| |

| |

|

| Rowland, p191 |

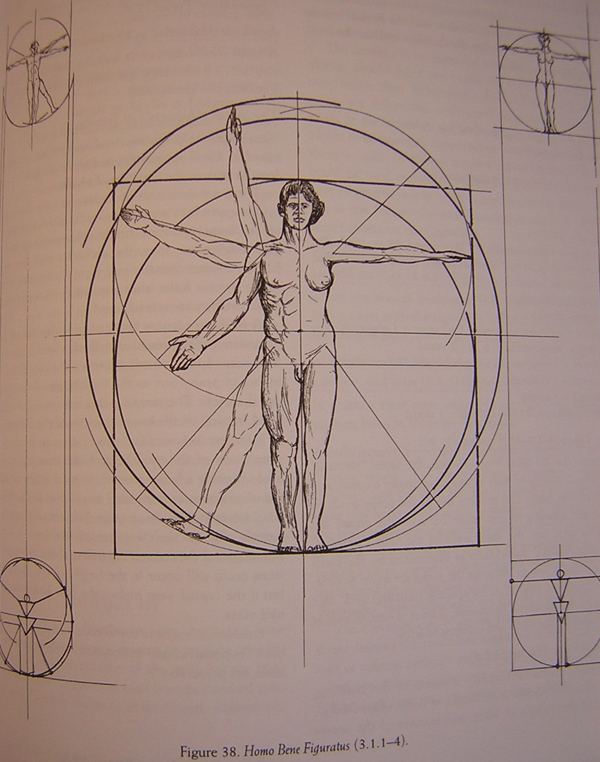

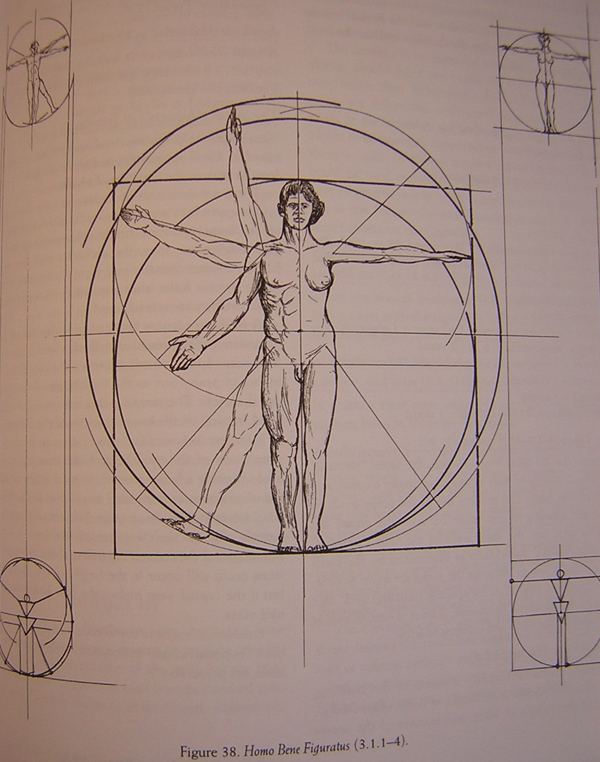

| Homo Bene Figuratus (Figure 1) |

| "Symmetria" of the human body according to Vitruvius. |

| |

|

ROMAN AESTHETICS: VITRUVIUS AND "SYMMETRIA"

Attention to proportion and “symmetria” in the human body and Roman architecture is evident in the Greco-Roman tradition in architectural treatises, basilical structure, and philosophical discourse. Vitruvius’ “De architectura” is the only surviving ancient treatise on architecture, likely written between 28 and 23 BCE. In it Vitruvius outlines six fundamental principles of architecture, of which two primary ones are “symmetria” and “eurthymia.” “Eurythmia” means gracefulness that leads to visual harmony and is most often achieved through “symmetria.” Following is a quote translated from Vitruvius’ treatise: “Symmetria is the proportioned correspondence of the elements of the work itself, a response, in any given part, of the separate parts to the appearance of the entire figure as a whole. Just as in the human body there is a harmonious quality of shapeliness expressed in terms of the cubit, palm, digit, and other small units, so it is in completing works of architecture.” (Rowland, 25; Figure 1) Plotinus, a Roman philosopher who lived from 204 – 270 CE, is considered to be the founder of Neoplatonism. He said that, “we see something as beautiful when it matches the beautiful form that is ourselves, that is, soul. We detect beauty by kinship, whether beauty in bodies or beauty in ideas, virtues, or ways of life.” (Miles, 40) Awareness of symmetry and proportion in the kinship of the human body and architecture forms an inextricable link.

The term “basilica” refers to the function of a building as that of a meeting hall and in early Roman society was a symbol of authority and social order. Architecturally, a basilica typically had a rectangular base that was split into aisles by columns and covered by a roof. There was an immense central aisle, colonnades, windows above the central aisle, and often a niche at the end. Basilicas were often constructed according to strict proportional guidelines; for example, “the columns of basilicas ought to be made as tall as the porticoes are going to be wide. The porticoes should be one-third the area of the central space. . .” (Rowland, 64) Upon entering a massive basilica the individual will feel tiny in comparison to the state, yet connected to the empire because each body and meeting hall was defined by similar tastes of symmetry. “Symmetria” is thus one of the most deeply rooted and continuous features of Greco-Roman thought, philosophically, artistically and aesthetically; it forms the basis for the Roman’s aesthetic sense of form, beauty, and harmony.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|