UW MEChA was much more than a political action group. Its efforts on behalf of Chicano students and community members included a multifaceted focus on social and cultural matters, as well as educational and political objectives. Cultural organizations and initiatives sponsored or supported by MEChA had a significant impact throughout the Pacific Northwest. The cultural promotions of MEChA included Teatro Campesino, Chicano/Latino graduation, Christmas “posadas,” Cinco de Mayo celebrations and other social events to meet the needs of students who were often far removed from their respective communities.42

MEChA students also sponsored lecture and film series, rap sessions, food and clothing drives, dances featuring acts like Little Joe, Eligio Salinas, and Los Lobos, as well as numerous Latino festivities and workshops. In addition, MEChA invited national leaders to the UW campus to talk to students about events taking place in other parts of the country. Such speakers included Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta of the United Farm Workers of California, Reies Lopez Tijerina of the Alianza Federal de Mercedes in New Mexico, Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzalez of the Crusade for Justice in Colorado,43 Patricia Vasquez of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF),44and various other guests ranging from artists and poets to leaders of the La Raza Unida Party.45

The Puget Sound gave rise to a dance troupe called Los Bailadores de Bronce (The Bronze Dancers), which soon developed into a long-standing community institution.46 Established primarily by faculty and staff from the University of Washington in 1972, the group evolved to include community members. Its purpose was to share Mexican dance, music, and cultural traditions with the community. As the years progressed, the dance group performed all over the West Coast and established itself as one of the oldest groups of its kind in the Northwest. Los Bailadores de Bronce contributed to the cultural development of the Chicano community in the Northwest, much like numerous other cultural initiatives undertaken during this period.

El Teatro del Piojo was another key cultural entity that developed under MEChA. Established in 1970 with the help of former UW professor Tomas Ybarra-Frausto, the theatre collective reflected the reality most Chicano students encountered growing up in rural Central Washington. Inspired by El Teatro Campesino,47 the UW group was comprised of students involved in both Las Chicanas and the Brown Berets, including Epi Elizondo, Bea Maldonado, Rita Trujillo, Eseban Sambrano, Genaro Apodaca, Sid Gallegos, Art Gallegos, and Cathy Cantu, among others.

El Teatro del Piojo was the first so-called ‘guerrilla theatre’ group in the Northwest. Many of the short skits, or ‘actos,’ were emblematic of this period of the movement, which emphasized the struggle in the fields as well as the experience of alienation through interaction with the dominant power structure. Throughout its existence from 1970 to 1979, the group performed all over the West Coast and became a member of Teatros Nacionales de Aztlan or TENAZ (National Theatre [Collectives] of Aztlan). El Teatro del Piojo later spawned a more traditional acting troupe known as El Teatro Quetzalcoatl, formed in 1975, which performed politically charged plays. Often referred to as the "voice" of MEChA,48 the theatre collective was instrumental in the emergence of the new Chicano identity in the Northwest.

The journal Metamorfosis, produced out of El Centro de Estudios Chicanos at the University of Washington, was another important cultural component of the Chicano movement. Though it lasted only from 1977 to 1984, Metamorfosis was instrumental in providing a forum for academic work on Chicano/Latino arts and culture in the Northwest during a period when the movement at the national level was beginning to wane. The journal was especially important considering the relative isolation of Seattle from the Chicano cultural hubs of the southwest. Chicano scholarly work in the Northwest would make an impression that, coupled with the emergent muralist art movement, influenced the discourse on Chicano/Latino identity in the State of Washington.

The Chicano Art Movement in the Pacific Northwest

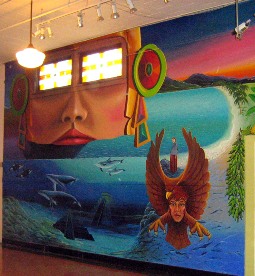

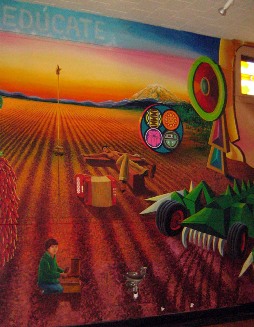

Seattle was the site of ground-breaking work in the field of Chicano art during the 1970s, with much of this work coming out of the University of Washington. Though Seattle lacked the cultural nutrients of cities in the Southwest, local painters Emilio Aguayo and Daniel Desiga became two of the most notable Chicano artists through their connections to artist collectives in California and the Southwest like the Rebel Chicano Art Front (RCAF), a Sacramento-based artists’ collective that served as a major link between Movimiento art in California and the Pacific Northwest. Seasoned artists from RCAF served as mentors for young Chicano artists in the Northwest and also produced three Pacific Northwest murals.49

This inspiration, infused with a distinct style centered in the Northwest, would be essential in the work done by Desiga. The only Chicano artist of this period who was native to the area, Desiga's work is emblematic of the Chicano experience in eastern Washington. Desiga’s personal history as a product of farm worker origins is reflected in his portrayal of male and female workers in rural eastern Washington. Some of his notable work includes the murals at El Centro de La Raza in Seattle,50 as well as a mural depicting Mexican farm workers, painted in 1990 in Toppenish, Washington. His style, distinct from his contemporaries, passionately engages the viewer in examining the socio-political context of Chicano life in the Northwest. Along with Aguayo, Desiga is perhaps the most influential Chicano muralist of the period.

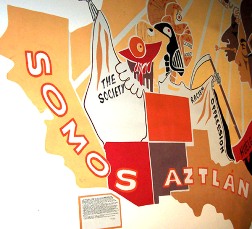

Originally from Denver, Colorado, Emilio Aguayo made his way to the Pacific Northwest in the early 1960’s. In 1971, while a student at the University of Washington, Aguayo painted Aztlán, the first Chicano mural in the region. The mural is now prominently displayed at the University of Washington's Ethnic Cultural Center.51 Upon completion of Aztlán, Aguayo wrote a description explaining the imagery and the color scheme used in producing the final piece:

This mural embodies the dawning of a new era for all the Spanish speaking people known as "LA RAZA." It is a cultural blend of past and present, of Indian heritage, of man struggling alongside women in the human conflict which is our drive for self-identity and self-determination. This painting is visual testimony that as part of this society, we are part of its past, its present and its future, something which as a people we will not be denied.

We are also a people with ideas in heart, mind, soul, and spirit who have lived a history of social oppression, yet…we have hopes for our future.

We are products of mankind--a composite of all races, all colors, yet more the blend of Spaniard and Indian which forms the mestizo precursor of the American Spanish-speaking, here 100 years and more before Columbus. We had a civilization which predates Christ.

Present and past symbols of our cultural history comprise this visual reality of early la raza art. Serpent and sun are symbols worshipped by our ancestors as gods of life and earth. Earth now is symbolic only of the nation within a nation we wish to build. The sun also symbolizes the dawn of our self-awareness, the revolution in the mind we so desperately need. The united farm workers flag is symbolic of first manifestations in 1965 of our current social movement. Man and woman symbolize the core of any society, the family unit. In this case, the Raza family is what kept us together in adversity.

Society is seen as a four-head monster of apocalypse, oppression and universal troubles of mankind. It is seen as we see it and live it. Society is thus a personification of oppressive evil now confront by social change which is good.

Aztlan is an Indian term for the land of the southwest, land of Spanish grants, area of our first beginnings, land of our greatest population concentration in five states.

Colors of this mural represents the five human races and the colors of earth in the southwest.52

The Chicano art movement of the 1970s produced the vast majority of the muralist imagery that is still around today. However, one key exception is a work painted in 1945 by world-renowned artist Pablo O’Higgins entitled, "The Struggle Against Racial Discrimination." O’Higgins moved to Mexico at the age of twenty and studied under the guidance of Diego Rivera.53 By the time he was commissioned to paint the mural in Seattle, he had already achieved status as one of the great muralists of the period. Although the O'Higgins mural predates the Chicano student movement, Chicano student activists played a key role in restoring it to public view during the 1970s, showing once again the importance of cultural politics in the Chicano movement.

The mural was commissioned by the Shipscalers, Drydock and Miscellaneous Workers Union in Seattle during a period when the union was involved in a number of civil rights campaigns, including protesting the police shooting of Eugene Mozee, a black service station owner, and supporting a fair employment practices law pending in the state legislature.54 Needless to say, this activism was ahead of its time. The civil rights movement would take another two decades to come to the forefront after the mural was completed in 1945. In addition to their progressive stance on civil rights, the Shipscalers were emblematic of the radical labor politics of the pre-World War II era. According to a UW Daily article written in 1977, "many of them were militant—drawing on the labor movements of the 1930’s. Seattle was a little more than 20 years away from its 1919 general strike and less than a dozen years away from a popular description of Washington state: ‘The 47 states and the Soviet Socialist Republic of Washington.’”55

Drawing upon this unique activity, O’Higgins coalesces both militant labor imagery and issues of civil rights. Staying true to his politics, he also incorporates Marxist imagery, much like his mentors did in the Mexican Muralist Movement of the previous decade. The painting is unique in the sense that it addresses the issue of social justice within a rights discourse and points at ideas that were before their time in the 1940s. As such, the O'Higgins mural is arguably the first of its kind in the Northwest, considering that few of the Mexican Muralists ventured to the region during that period.

The piece was first suppressed in 1955 during the McCarthy era and then forgotten due to institutional negligence. It remained in storage until 1975 when, as Lauro Flores observes, "the impetus of the Chicano movement forced its restoration and vindication."56 The politics of public art were evident as subject material deemed too controversial was set aside for a prolonged period until pressure from El Centro de La Raza and UW MEChA convinced the University of Washington to restore the mural. Now displayed in Kane Hall, the mural is invaluable not only as a part of the history of the Chicano community of this area, but also of the collective history of Washington State.

Even as the Chicano Movement subsided in the 1980s, the main contributions to the arts lived on through the imagery of the muralist movement. Despite the geographic isolation from cultural hubs in the Southwest, the Chicano/Latino community has forged an identity that is uniquely its own, that incorporates the geography of the Pacific Northwest into its art. As Tomas Ybarra-Frausto has written, the “acute sense of isolation and dislocation is tempered with a striving to generate new horizons and new mythologies with an aim to reflect through literature diverse aspects of Chicano life in the region.”57 This identity survives despite the distance from the longer established communities to the south; it is a reflection of La Raza’s relevance and appeal in the northwest corner of the U.S.

The Fight for Chicano Studies

The recruitment of increased numbers of Chicano/a grad students, faculty, and staff had been at the center of students' demands since the arrival of the first Chicanos to the UW campus. This battle between students and university administration would only intensify throughout the 1970s and early 1980s. At times, frustration at the slow pace of change led to demonstrations, the occupation of buildings, and the filing of complaints to state agencies dealing with civil rights.58

One of the first actions occurred in March of 1972 when students organized a moratorium to stress the importance of hiring Chicano/a faculty at the UW.59 Two years later the issue remained at the forefront of student grievances. In May of 1974, forty students led by UW MEChA occupied the office of the Chair of the Psychology Department at UW.60 The sit-in was in response to inaction by the Psychology Department in providing equal representation of Chicanos at the administrative, faculty, staff and graduate student levels.

As the month progressed, activity intensified as information about hiring practices came out. On the 13th of May, between 75-100 students occupied and ransacked the office of the Dean of the College of Arts & Sciences.61 The protest was a result of the college's decision not to hire Dr. Carlos Muñoz as a new professor at UW, as well as the university's general unwillingness to recruit Chicano faculty. The Munoz issue would be bitterly debated over the next several years. According to former student activist and current UW professor Erasmo Gamboa, “that incident is telling of the difficulty and the problems in working within the University for change. The University departments, faculty are not always accepting of change”62 Muñoz eventually joined the Department of Ethnic Studies at the University of California at Berkeley, becoming a world-class scholar and one of the most influential Chicano political scientists.

The decision to not hire Munoz was still fresh on the minds of many as the 1974-1975 academic y ear started. With the hiring issue still unresolved in the spring, a crisis developed when support for the student protests led to the firing of the head of the Chicano division of the Educational Opportunity Program. Then in May the UW fired two more Chicano administrators for their participation in activities protesting the university’s hiring practices.63 As the week progressed, Chicano staff and faculty members resigned in solidarity, leaving the Chicano Studies Program with an uncertain future.64 For its part, MEChA responded with a resolution condemning the firings. A week later, nearly 2,000 students converged on the administration building at the University of Washington.65 UW MEChA and the ASUW called for a two-day boycott of classes to protest the hiring practices of the University's affirmative action program.66 As with previous actions, this cause was met with support from various student groups who joined the boycott in solidarity.

Over the summer, the President of the University made an official apology and started dialogue with faculty who had resigned. In the end, many of the staff and faculty rescinded their letters of resignation and were reinstated.67 This put MEChA at odds with faculty as students felt they were marginalized during the talks and the primary issue was not addressed.

The animosity between students and faculty during the hiring debates further took shape in 1978 during what students deemed the transformation of the EOP programs. The reorganization of EOP was met by resistance from students who felt their voices were being silenced and that the high administration at the Office of Minority Affairs was making decisions without consulting students who would be affected by the proposed changes. UW MEChA occupied the Chicano Division of the Educational Opportunity Program and organized a ‘sick-out’ with counselors to protest the reorganization of the EOP program at UW.68

The struggle expanded over the next two years, culminating in the occupation of Schmitz Hall, the central administration building at the University of Washington. Twenty Asian and Chicano EOP students occupied the offices of EOP Vice-President Herman Lujan on May 21st, 1980, demanding his resignation and an end to the new restrictive admissions practices.69 Throughout the week's protests, over 78 students, staff and community members were arrested.

The 1980s signaled the end of many of the initiatives pushed by the student movement. An ideological shift away from cultural nationalism was one factor in the decline of movement activism. The internal fissures present in a student movement that included cultural nationalists, Chicano Marxists, as well as students who advocated for a moderate stance and the conversion of the group into a 'social' organization also hampered the movement in the 1980s. This process played out with various MEChA chapters in the Southwest as well.

Legacy of the Chicano Movement

Almost four decades after it began, the Chicano Movement still has a visible impact. As a result of activism at the grassroots level on the part of various communities of color, there has been a fundamental change in how people talk about race, which is a lasting effect of the broader Civil Rights Movement. The most visible results of the Chicano Movement are still primarily within academia, with the establishment of numerous student centers at college campuses all over the country that cater to students of color as well as the establishment of Chicano Studies Departments, research centers, academic journals, and so on.

The literary and art movements of the 1970s have also left an indelible mark on the Chicano/Latino community. The production of art centered on issues such as racism, human rights, and equal access to education and employment continues today. The discourse has also expanded to include issues of class, gender, nationality, and cultural identity.70 Though the Chicano art movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s has waned, the work these artists left behind continues to inspire today’s Chicano youth and influence the discourse on Chicano culture.

At the local level, the movement gave rise to community institutions, helping to build a Chicano community where none had existed before. Alliances with other communities of color were essential to the movement’s success. The broad alliance for civil rights that emerged allowed for further progress within the Chicano community at a time when the local population was miniscule in comparison to the urban Chicano communities of the Southwest. This collaboration across racial lines was a unique development in the Northwest, and is an integral part of the legacy of civil rights activism in the region. The development of the Chicano community was also a result of work that was done on both sides of the state, with activism in the Yakima Valley providing an impetus for much of the activist work in the Puget Sound region as people, especially students, migrated to western Washington.

Activist youth organizations are also still operating on many campuses. MEChA declined during the 1980s, with low numbers at many campuses and many chapters becoming inactive, but has experienced a revival since the mid 1990s, partly in response to the massive anti-immigrant backlash in California, as well as the attacks on affirmative action and other programs throughout the country.71 The first National MEChA Conference was organized in 1994 at Arizona State University. This was one of the first attempts to unite the various chapters from around the country under similar goals. A National Coordinating Committee was formed in the wake of the conference, as were regional bodies, such as the Pacific Northwest MEChA Region, to take on issues at the local level.72 Essentially, this meant that regions functioned as semi-autonomous chapters with the ability to formulate their own policies in accordance with what was needed. As such, the Pacific Northwest had a different focus than Southern California.

During this period, numerous colleges and high schools would establish MEChA chapters for the first time, making the student-led organization one of the largest in the country, with approximately 250 chapters from the West Coast all the way to the Northeast. It was also during this time that the organization re-evaluated its stance on key issues such as the struggle of indigenous peoples against neo-liberal economics and support for human rights and economic justice, among others. The new stance was outlined in the MEChA Philosophy Papers that were drafted in the late 1980s and early 1990s and officially adopted by the National Coordinating Body.73

The late 1990s witnessed renewed activist activity centered on opposition to I-200 on the UW Campus. The initiative was voted into law in November of 1998, officially removing the affirmative action policies instituted at the state level in the 1960s and 1970s. The opposition to I-200 echoed the concerns of the previous generation of Chicano student activists as the issue of access to education once again came to the forefront. An immediate impact was felt after the initiative passed with the dramatic drop in students of color accepted into public universities. As a result, MEChA joined forces with other organizations to organize and implement informational events to assist prospective students in the process of applying to schools. UW MEChA has organized the Adelante Con Educacion Conference every year for the last twelve years. The conference is geared toward the outreach and recruitment of prospective Chicano students from throughout Washington State.74

In 1999, the UW MEChA chapter once again mobilized students. This time the occasion was the World Trade Organization ministerial, held in Seattle in December of that year.75 The contingent based out of the UW dressed in black and red as a sign of solidarity with the Zapatistas in Chiapas, Mexico. Since 1994, the Zapatistas have waged a battle against neo-liberal economic policy, which not only makes living conditions worse for the poor and working classes, but also threatens the very existence of the indigenous people in Mexico’s poorest state.76 The “Battle in Seattle,” as the WTO demonstrations were called, disrupted the meetings and effectively ended the round of talks. More importantly, the demonstrations drew international attention to the negative ramifications of globalization for the world’s underclass.

Since the turn of the century, UW MEChA has been active in issues ranging from support for House Bill 1079 in 2003, which allows undocumented students to pay in-state tuition, to opposition to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as opposition to U.S. Intervention in Latin America. 77

The spring of 2006 saw the emergence of the Immigrants Rights Movement at the national level in opposition to proposed House Resolution 4437.78 A few days prior to the start of Spring Quarter at the UW, there were massive rallies organized in Los Angeles and other major urban centers,79 including mass walkouts from high schools throughout the Southwest. It took only a few days before the first protests were organized in the Yakima Valley, where 650-700 students walked out of Davis and Eisenhower High Schools, and in the Columbia Basin, where Pasco High students were aided by Columbia Basin College MEChA. Approximately a week after the Los Angeles rally a march was organized in Yakima.80 From there, the movement spread to colleges and universities as the Pacific Northwest MEChA Region (PNMR) organized three simultaneous demonstrations at Western Washington University, the University of Washington, and Central Washington University.

In organizing the event, the PNMR made it a point to emphasize human rights, not strictly Latino rights, and to resist attempts by the media to portray the protests as Latino-centric. It was especially important for demonstrators to be inclusive of other immigrant communities, as the immigration bill under consideration would also adversely affect emigrants from Asia, Africa, and Europe, in addition to the Americas. The action was a success, with the event making it onto the front page of the University of Washington Daily and sparking widespread discussion on campus.

At the City level, an organization called Comite Pro-Amnistia y Justicia Social (Committee for Amnesty & Social Justice) took the lead in organizing various events. The Committee, formed in 1999, was created with the intent of organizing Latino immigrant communities around issues of civil, labor, and human rights.81 The group organizes many events throughout the year, including an annual march on May 1st in solidarity with immigrant workers. The first major immigration rights march was organized on March 18, 2006. The march received little attention in the press, despite having over 5,000 participants. This demonstration preceded the massive movement that would evolve later on that month.

On the first National Day of Action that was called for by organizers, massive marches were organized simultaneously across the country.82 On April 10th, Seattle hosted one of the largest non-violent marches in its history, with approximately 50,000 participants filling the streets.83 According to the Seattle Times, the march registered zero arrests.84 The second march on May 1st had similar results as it registered approximately 60,000 participants and coincided with a national one-day boycott of all goods. The boycott received support in Latin America as news of the movement made the international press. The massive groundswell of opposition to H.R. 4437 has stalled the bill’s progress through Congress for now. It appears as though there will be no action until after the 2006 elections.

The immigration rights movement still lacks direction as to what strategy it will employ and what objectives it will seek. It emerged organically as many people became aware of the implications associated with the anti-immigrant backlash. However, the fact that the movement did emerge highlights the importance of the issue and the need to address it in most communities. The idea of the instant criminalization of millions of people forced millions more to take a strong stance for the rights of all individuals regardless of race, ethnicity, national origin, or legal status.

There is hope for the future. The student walkouts this spring surpassed the L.A. Blowouts of 1968 as the largest mass demonstration of high school students in American history. The marches also stand as one of the largest mobilizations of people for a non-violent movement. It remains to be seen what will happen next, but as many of the marchers pointed out this spring, “today we march, tomorrow we vote.”

Copyright(c) Oscar Rosales Castañeda 2006

McNair Scholarship project 2005-06

42 La Historia de MEChA, Internal Document for MEChA Executive Board, 1987, MEChA de UW Archives.

43 The Crusade for Justice was a community organization founded by Gonzalez in Denver, Colorado in 1966. The organization operated a school, a curio shop, a bookstore and a social center. It was most notable for introducing the Chicano urban struggle and incorporating youth into the emergent Chicano Movement.

44 In 1968 the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF) was organized in San Antonio, Texas. It was modeled after the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

45 La Raza Unida Party’s platform touched on economic development, the system of justice in the United States, the role of women, immigration, the selective service system, international affairs, natural resources, transportation, health, welfare, and housing among others (see Carlos Muñoz. Youth, Identity, Power: The Chicano Movement. New York, N.Y.: Verso, 1989. p. 99-126).

46 The Bailadores de Bronce was one of the few groups founded during the early 1970’s that is still in existence. The group performs at various events throughout western Washington; see, http://www.bailadoresdebronce.org/

47 Initiated as a farmworker group, El Teatro Campesino was established by Luis Valdez in 1965. It publicized the struggle of the farm workers and Chicanos in one-act plays. The collective was also instrumental in helping to establish other theatre groups.

48Jesus Rodriguez Interview. 3 March 2006.

49 Sid White, Pat Maheny-White “Recent Developments: Chicano and Latino Artists in the Pacific Northwest in the 1970s and 1980s.” The Evergreen State College Library | Chicano/Latino Archive. 2004, p. 24,

<http://www.evergreen.edu/library/chicanolatino/docs/exhibitcatalog04.pdf>.

50 Chicano and Latino Artists of the Northwest Project at The Evergreen State College. <http://www.evergreen.edu/library/chicanolatino/>

51 Brief description of the Aztlan mural at the UW Ethnic Cultural Center’s Chicano Room, <http://depts.washington.edu/ecc/rooms_chicano.htm>

52 Emilio Aguayo, 1972, UW Ethnic Cultural Center; The Ethnic Cultural Center and Theatre (ECC/T) opened its doors in the fall of 1972 at the University of Washington. It was the first center of its kind in the nation, making it the first building owned by a university to serve primarily people of color and one of the first to be a hub for cross-cultural exchange (For additional information, see < http://depts.washington.edu/ecc/aboutus.htm>).

53 Diego Rivera was one of the leading figures in 20th Century Art. Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros are know as ‘los tres grandes,’ and were at the forefront of the Mexican Muralist Movement during the cultural renaissance of post-revolutionary Mexico. The social realist style employed by the muralists would have a profound impact on Latin America Art and would serve as inspiration for the Chicano Art Movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

54Bruce Johanson, “Mural still controversial 30 years later.” University of Washington Daily. 2 Dec. 1977, p. 12.

55 Johanson, “Mural still controversial 30 years later.”

56 Lauro Flores, “A Two Hundred Year Presence: Chicano and Other Latin American Artists in the Pacific Northwest.” The Evergreen State College Library| Chicano/Latino Archive. 2004, p. 7

57TomasYbarra-Frausto.” Chicano Culture: Everyday Life in the Pacific Northwest.” The Evergreen State College Library | Chicano/Latino Archive.2004, p. 19<http://www.evergreen.edu/library/chicanolatino/docs/exhibitcatalog04.pdf>.

58 Rodriguez, MEChA Newsletter University of Washington, 1981, p. 1-2, Jesus Rodriguez Papers, MEChA de UW Archives.

59 “Chicanos ask for moratorium support,” U of W Daily. 3 Mar. 1972

61 Dean Beckmann's office trashed during sit-in (for Carlos Munoz) U of W Daily 14 May 1974

62Erasmo Gamboa Interview, Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. 1 November by 2006 Trevor Griffey and Angelita Chavez

63 UW fires two Chicano administrators U of W Daily 7 May 1975

64 20 Chicanos resign in wake of firings U of W Daily 8 May 1975

65 Huge crowd attends demonstration against UW hiring practices U of W Daily 14 May 1975

66 ASUW calls for strike in support of Chicanos U of W Daily 9 May 1975

67 Chicanos plan summer talks with University U of W Daily 23 July 1975

68 The Daily Jalapeño, EOP Take-Over Edition, UW MEChA Newsletter, 21 May 1980, MEChA de UW Archives.

69 The Daily Jalapeño, 21 May 1980, MEChA de UW Archives.

70 The Philosophy of M.E.Ch.A. last revised at 1999 National MEChA Conference in Phoenix, Arizona.

71Acuña, Occupied America, p. 391-95

72 The Pacific Northwest MEChA Region (PNMR) is a student organization that is coordinated by all the active MEChA chapters in Washington and Idaho, including universities such as the UW, WSU, WWU, EWU, CWU, and the various community colleges and high schools that are affiliated and recognized by the member organizations.

73 The Philosophy of M.E.Ch.A.

74 See, http://students.washington.edu/mecha/ace.html

75 Interview with Miguel Bocanegra and Randy Nuñez, The WTO History Project, <http://depts.washington.edu/wtohist/interviews/Bocanegra,%20Nunez.pdf>

76 Acuña, p. 380

77Josh Fredman, MEChA Rallies for Legislation, UW Daily 23 Jan. 2003, Online Edition,

78 H.R. 4437 is available at <http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/z?c109:H.R.4437.RFS:>

79 The first major march took place in Chicago, Illinois on March 10, 2006. The Chicago march attracted approximately 300,000 participants. The movement would take off in Los Angeles with one of the largest demonstrations in the city’s history which brought 700,000-1 Million people to the steps of L.A.’s city hall.

80 The march in Yakima held on April 2, 2006 attracted over 4,000 participants.

81 For more information, see <http://www.comiteproamnistia.org/eng.html>

82 There were two major events calling for National Action which took place April 10, 2006 and May 1, 2006. Both events were organized on a scale previously unseen as marches were held all over the United States, from the major urban centers, to small towns.

83 Estimate varies from a conservative 45,000 to 65,000.

84Lornet Turnbull, “Immigration Rally floods the Streets.” The Seattle Times. 11 April. 2006, p. 1, 10.

_Page_1_Image_0001-250.jpg)