Organized by the Communist Party as the Cold War was getting underway, the Seattle Civil Rights Congress tried to advance the struggle for racial equality while defending radical organizations and leftwing unions from attacks by anti-communist crusaders and prosecutors. A legal defense organization that provided attorneys and raised money for defendants, the CRC also engaged in public education and protest campaigns, winning some important victories on both fronts. The Cold War marked a key turning point in civil rights politics. It marked the end of a labor-based civil rights movement that combined campaigns for worker’s rights and racial justice, and the end of a broad coalition in which the Communist Party and left-wing unions played important roles. That coalition was torn apart by the Red Scare politics of the late 1940s and early 1950s, replaced by a more singularly focused civil rights movement led by the NAACP and other organizations that rejected links to radicalism and often to labor. The Civil Rights Congress emerged at that transition point and for a time kept alive the dream of a radical labor-based civil rights movement.

Aubrey Grossmen, West Coast Director of the Civil Rights Congress, spoke to that vision at a 1949 meeting of the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union on the Seattle waterfront. "The people with the most interest in breaking unions also have the greatest interest in attacking the Negro people and minority political parties, because only they can profit from such attacks. The purpose of these attacks is to split and divide the working people to prevent them from fighting as effectively as possible for better conditions."1 Grossmen went on to discuss the Cold War realities of Seattle, stating: "They know that the workers are more clearly realizing the necessity of Negro-white unity to win their demands. So they are now attacking progressive ideas themselves. They fire professors for their political beliefs. They frame up six Negroes in Trenton. They place a minority political party on trial…"2 This link between union politics, civil rights and civil liberties encapsulates the underlying ideological aims of the Civil Rights Congress. Workers rights and civil rights were indivisible. Fighting for both was the key to racial justice.

Launched in Detroit in 1946, the Civil Rights Congress represented a merger of three Communist-linked organizations: the National Negro Congress, International Labor Defense, and the National Federation for Constitutional Liberties. William L. Patterson, a black communist attorney who had led the ILD, became the Executive Secretary of the Civil Rights Congress and guided it until its demise in 1955. Seattle was one of the cities where the CRC proved most effective. Described by Patterson as one of strongest chapters in the nation, the Seattle Chapter of the CRC combined impressive membership numbers with aggressive mobilization of that membership.3 At its peak in 1952, Washington State CRC Chapters boasted 500 members. Seattle's chapter led the state with 350 members, 75 of which were black. It was one of three national chapters that consistently paid dues, no small achievement during the difficult Red Scare years.4

Background

Communists had been doing civil rights work in Seattle since the 1930s and the CRC was not so much a new organization as a renamed and refocused one. The Communist Party (CP) had been one of the first political parties to openly champion racial equality in Washington State. In the early 1930s, the Party elevated several black members to leadership positions, including Revels Cayton, son of former newspaper publishers Horace and Susie Cayton. Revels Cayton ran on the CP ticket for Seattle City Council in 1934 while serving as district secretary of the International Labor Defense, a CP legal defense and civil rights organization. That same year he founded a chapter of the League of Struggle for Negro Rights, another predecessor to the Civil Rights Congress.5

Starting in the mid 1930s, the CP had cooperated with other organizations working for civil rights, including the NAACP and later the Seattle Civic Unity Committee(CUC). Before 1946, Seattle's civil rights movement functioned in an atmosphere of tacit cooperation across political lines, with the Communist Party being one of many groups struggling for civil rights.

The Washington Commonwealth Federation (WCF) and the Washington Pension Union (WPU) were important to the CP's coalition strategy. Both played crucial roles in Seattle's civil rights scene, the former as a Democratic Party caucus group, the latter as an advocacy group for pensioners and underprivileged children. Though branded as "Communist fronts" by detractors, both groups mobilized a wide range of supporters. The WCF became highly influential in the late 1930s, electing dozens of left-wing democrats to local office, some of them Communists.6

Jennifer Phipps explains that by the "late 1930s, Party members were in key positions and mostly able to control these mass organizations with their broad spectrum of activists and supporters behind initiatives, candidates, and issues that advocated a diverse reform agenda."7 Phipps goes on to state, "Communists constituted a clearly identifiable segment on the left wing of the Democratic Party. Through such a solid institutional base they functioned as a very strong and visible political pressure group."8 This aggressive visibility did much to establish the CP as a champion of social reform. On the votes of this caucus conglomerate, WPU president William Pennock won a Washington State House of Representatives seat from 1938-1944, representing a massive lobbying base.9

By the time the WCF disbanded in 1945, the WPU had replaced it as the most effective popular front, remaining active well into the Cold War years. The WPU existed ostensibly to reform pension law in Washington State, but it also represented a successful union and civil rights coalition with heavy CP involvement. The WPU's primary aims–raising pensions and funds for underprivileged children–were two welfare issues that resonated with a broad social base. Margaret Miller argues in her dissertation on labor and pension politics in Washington State that the WPU "tied pension politics to a variety of issues, causes, and communities seemingly remote from Old Age Assistance advocacy. This 'nexus' between labor, the aged, women, and African-Americans, among others, became the hallmark of Popular Front and Pension Union politics."10 A high degree of mobilization around these issues resulted in serious lobbying power and legitimacy for the WPU, despite its radical ideology.

Even among more conservative civil rights groups, efforts towards cooperative action persisted in Seattle through the early 1940s. In 1944, Seattle Mayor William F. Devin founded the Seattle Civic Unity Committee (CUC) to promote better relations between the races. A very moderate organization, the CUC became involved in efforts to counter racial discrimination and win rights for minorities, including a campaign for the passage of a Fair Employment Practice law in Washington Legislation.11 Although most board members were anything but radical, the inclusion of the leftist attorney John Caughlan as well as CP member and Seattle National Negro Congress leader Carl Brooks demonstrated the spirit of cooperation that prevailed in the pre-Cold War civil rights movement.12

Cold War Isolation

After World War II and Churchill's emphatic warning that an "iron curtain" had descended across Europe, the global political climate underwent a drastic change. In Seattle, CP members found old partners suddenly reticent to pursue previously common goals. Old coalitions failed to command cooperation and the political atmosphere became increasingly hostile for Communists. By June of 1946, the Civic Unity Committee (CUC) had purged both Caughlan and Brooks from their ranks. It was a move that would characterize the next decade of civil rights engagement. The CUC claimed to have never "had the problem of left-wing infiltration which has been a threat to many comparable committees in other parts of the country." With a tidily conservative committee, the CUC achieved a state Fair Employment Practice law in 1949, attributing earlier failures to the presence of leftists on the Executive Board.13

As the political left found itself increasingly isolated, the state legislature approved the creation of the Canwell Committee in 1947, charged with investigating Communist influence in Washington State. In advocating the formation of the committee, State Representative Albert Canwell argued:

These are times of public danger; subversive persons and groups are endangering our domestic unity, so as to leave us unprepared to meet aggression, and under cover of protection afforded by the Bill of Rights, these persons and groups seek to destroy our liberties and our freedom by force, threats and sabotage, and to subject us to domination of foreign powers.14

The Canwell Committee, also known as the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), launched an aggressive investigation of organizations including the Communist Party, the Seattle Repertory Theater, the University of Washington, and the WPU.15

Launching the Seattle CRC

The Canwell Committee created a crisis for the CP and its allies, as did the announcement of federal investigations and prosecutions of CP members under the Smith Act. The Seattle chapter of the Civil Rights Congress (CRC) was created in part to respond to the threat. The CRC would lower the visibility of the official Communist Party while providing a vehicle for aggressive opposition to the witch-hunts.

In 1948, two years after the formation of the national CRC, The New World, a weekly newspaper published by the WPU and Seattle Communist Party, ran an article declaring: "Clearly the people must quickly forge an effective weapon. It seems to _The_ _New World_ that a Washington State Chapter of the American Civil Rights Congress is needed right now. Such an organization is needed to assist in the national defense of the 12 communist leaders who will go on trial Oct. 15th."16 WPU Vice President John Caughlan soon announced the formation of Washington chapters. Caughlan and other WPU leaders saw the need for a legal and publicity minded organization to defend WPU interests. As Margaret Miller observes, in June of 1948, "the WPU state board arranged to have the CRC's bulletin sent to every WPU local each month and recommended that the bulletin be read at local meetings."17 Longtime WPU Vice President John Caughlan was instrumental in launching the Seattle CRC. Margaret Miller argues that

[the] close relationship between the WPU, with its much larger membership, and the CRC helps explain its vitality. Sympathetic Pension Union Stalwarts, whether CP members or not, spread the CRC message widely in the pages of the Pension Builder, at local meetings, and in remarkably prolific letter- writing campaigns. Pension Unioners could also be counted on to attend various CRC boycotts, protests, and fund-raisers.18

The Washington CRC expanded quickly, with chapters forming out of existing WPU groups across the state. With the WPU as a parent organization, the CRC found wide support, access to thousands of signatures and a membership ready to donate to a multiplicity of causes. In effect, the Seattle CRC served as the legal arm for the much larger WPU.

The Seattle CRC outlined itself "as an educational and political association" and in 1948 established headquarters at 215 Bay Building.19 John Daschbach, founder and acting secretary of the Seattle CRC, and John Caughlan, principal attorney to the Seattle CRC and Vice President of the WPU, penned the mission of the local chapter:

To affect public policy with respect to, and oppose, discrimination against, or prosecution or persecution of, persons, by reason of their race, creed, color, nationality or national origin or political persuasion or affiliation, and at the present time, especially, to oppose such discrimination or persecution with respect to the Negro people, and to affect public policy to assure full participation of Negro people in the political, economic, civic and cultural life of the community, state and nation.20

This comprehensive affirmation of civil rights, with its emphasis on race and political persuasion, positioned the CRC as a form of legal, social and financial aid to a broad constituency. Its main goal was to fight discrimination and to affect civil rights change in public policy. The Seattle chapter managed to make these goals part of community life in a dynamic and aggressive way achieved by few other chapters of its size.

Daschbach and Caughlan were the backbone of the Seattle CRC. Daschbach, a graduate of the University of Washington with a degree in political science, helped found the Pacific Northwest Labor School and was heavily involved in both the left and the labor social scene.21 Originally from Missouri, John Caughlan earned a degree at Harvard Law School in 1935 and moved to Seattle shortly thereafter.22 As early as 1937 Caughlan began defending CP members, earning a reputation as a "commie lawyer."23 Historian Gerald Horne argues that locally the Seattle chapter "was often the most organized, if not the only force fighting back militantly."24 This militancy was chiefly a product of the fluidity of CRC membership and the aggressive leadership of Daschbach and Caughlan.

Operations and Membership

As indicated above, CRC growth depended largely on the WPU. In rural chapters, both CRC and WPU meetings were conducted by the same people in the same spaces, making it difficult to track CRC membership. The number of signatures collected by the WPU is staggering during this period; in May 1948, minutes from the WPU general board meeting record 72,542 signatures for the passing of Initiative 172, a bill increasing the state social security cap from sixty to sixty-five dollars.25 Though the WPU had broader appeal and less radical aims than the CRC, access to this membership pool afforded the CRC massive signature drives and a vast fundraising potential. Perhaps more importantly, ties to the WPU created greater flexibility for CRC membership by minimizing political risks associated with the smaller, more aggressive organization.

Though the WPU was by far the largest base, the CRC also drew heavily from the rank and file of other unions, especially waterfront unions, where issues of race, political affiliation, and labor rights converged with more immediacy than anywhere else in the city. The Marine Cooks and Stewards Union, the Cannery Workers Union, and International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) locals provided key support for the CRC. Both Marine Cooks and Cannery Workers had large African-American and Filipino-American membership, as did Local 9 of the ILWU.

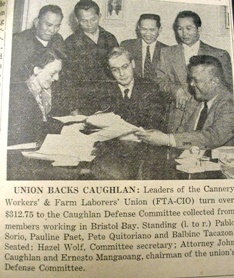

John Caughlan handled legal affairs for Cannery Workers Local 7 from the 1930's to the 1950's, suggesting a strong link to the CRC. The John Daschbach papers provide a record of correspondence between the CRC and ILWU Local 9 that suggests joint membership and shared concerns between the two organizations.26 While the CRC provided affordable and effective legal backing for these and other unions, union members supported CRC actions generously, both socially and financially.

The Marine Cooks and Stewards (MSC) responded to the CRC with more enthusiasm and commitment than most unions, providing strong backing for the local Chapter. In 1949, MCS’ newspaper _The Voice_ promoted a signature drive in which the "newly formed Maritime Committee of CRC [had a] goal of 10,000 signatures" protesting the arrest of twelve high-ranking CP members.27 Other signature drives helped the CRC contest the Mundt Bill, the Canwell Committee, and the treatment of the "Scottsboro Boys," a group of nine black men charged in a rape case central to the formation of the national CRC. The Seattle MCS local was heavily involved in CRC functions, hosting fundraiser dances and evening speeches in the union hall. _The Voice_ consistently ran articles promoting CRC actions and fund drives, informing members at sea about progress on pertinent CRC court cases.

Social change through dissemination of information and education, as in the case of The Voice, was one of the primary aims of the CRC. The national CRC office ran a publication campaign that the Seattle Chapter pushed militantly and with great success. From We Charge Genocide,an indictment of US racial discrimination that was presented to the United Nations, to the Seattle CRC's bi-monthly magazine, the Washington Liberator, which reached a readership of eleven hundred, CRC publications were widely circulated.28 These publications, along with the nationally produced monthly CRC Action Bulletin, provided a crucial sense of unity for CRC members. As members from chapters across the country signed petitions for high profile cases like the 12 Communist Smith Act Defendants, the Trenton Six, and Willie McGee, the _Action Bulletin_ kept local members aware of these national campaigns.

In July 1948, following the arrest of twelve top leaders of the CPUSA, the Seattle CRC sent scores of telegraphs bearing signatures of local members and sympathizers. The telegrams, addressed to President Truman read:

This is the first time since American people repudiated alien and sedition acts that an administration has sought to take away from the people their inalienable right to pass judgment at the poll on any political party, including the communist. We are exercising our right of petition by demanding that his threat to the rights and liberties of all be repaired through the immediate dismissal of these unprecedented indictments.29

Hundreds of donations ranging from fourteen to twenty-five cents, from people across the state, accompanied the signatures. While the donations might have been humble, these contributions serve as an indicator of the CRC's widespread support. The signature campaign was the first of many.

Fighting for Civil Rights

Despite its increasing isolation from other civil rights organizations, the CRC was determined to take a leading role in the struggle for racial equality. The founding charter committed the Seattle organization to "oppose such discrimination or persecution with respect to the Negro people, and to affect public policy to assure full participation of Negro people in the political, economic, civic and cultural life of the community, state, and nation."30 Most local CRC civil rights work involved spreading awareness and raising funds for national campaigns, as Seattle lacked a high profile race case for the local chapter to rally around. National cases such as the Trenton Six, Willie McGee, and the Martinsville Seven were well represented in the _Action Bulletins_ and Washington Liberators.

In November of 1949, the CRC sponsored a fundraising event at the Marine Cooks and Stewards hall with Bessie Mitchell, sister in law to one of the Trenton Six.31 _The Voice_ quoted Mrs. Mitchell as stating that she had "contacted the Justice Department, Civil Liberties Union, NAACP, and 'None of them offered any help.' Finally she contacted the CRC, which took up the case and brought the story of the Trenton Six to the public," winning a re-trial.32 The CRC's agreement to publicize the Trenton Six at Bessie Smith's request combined the primary tactics the Seattle CRC employed in the struggle for civil rights--fundraising, education, and legal aid.

The Seattle CRC also played an important role in publicizing local violent attacks on black community members. _The Voice_ reported the CRC as the only organization willing to "fight the case of Brother Henry Griffin, former MCS member blinded on a torpedoed shop during the war, who, according to evidence obtained by the CRC, was beaten in the Seattle Jail."33 Cases like these earned the CRC a local reputation for aggressive legal action where other organizations shied away from certain cases, particularly those with left-leaning minority plaintiffs.

In February 1950, "Adolf Samuels, unemployed building laborer, was arrested while quietly drinking beer and beaten insensible."34 The jury promptly acquitted the officers involved. The CRC tried to intervene, publicizing the incident in its Action Letter. Daschbach visited Police Chief Eastman and promised legal aid to anyone victimized by the police.35

When "dixiecrat hoodlums" broke the windows of the Washington State Labor Council for Negro Rights office in May 1951, the Seattle CRC posted a $1,000 reward for "information leading to arrest and conviction of the night-riding vandals guilty of the sneak stoning."36 This consistent and visible commitment to both publicize and subsidize legal help for local abuse cases positioned the Seattle CRC as a viable civil rights organization long after it had been branded a "Communist front."

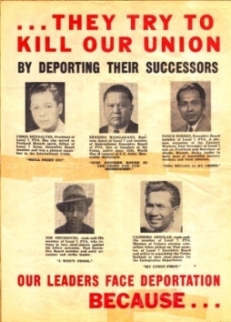

The McCarran Act of 1950--which mandated the revocation of citizenship and deportation of "subversive" naturalized citizens--had serious implications for some local unions. With its passage, the predominantly Filipino Local 7 Cannery Workers Union faced the deportation of many of their leaders, such as Ernesto Mangaoang. Caughlan took the case with CRC backing. Micah Ellison writes, "The case worked its way up to the Supreme Court in 1953 and was concluded by an issue brought up by the famous defense attorney John Caughlan, who argued that Mangaoang never technically "entered" America as an alien because he traveled from the Philippines while it was still an American territory."37 Caughlan's successful defense of Mangaoang and other Filipino union leaders was a decisive victory for the CRC, and solidified the implicit link between unions, civil rights, and civil liberties.

While the CRC was consistently involved in legal battles, equal emphasis was placed on raising local civil rights awareness. Some of the most significant local victories occurred not in courtrooms, but in civic settings. In 1951 the Seattle CRC and the WPU petitioned the Seattle City Council to pronounce the week of February 8-15 Negro History Week--and won. The CRC sponsored an evening to celebrate the victory, with a lecture on the writings of Frederick Douglass at MCS Hall by former University of Washington Professor Joseph Butterworth of Canwell Hearing infamy.38

In 1952, the Seattle CRC also protested a minstrel show slated for March at the Monroe Reform School, describing blackface as a "reactionary drive to insult the Negro people by 'jokes' and ridicule."39 A month later, _The_ Washington Liberator, a local CRC publication, reported that the show had been canceled due to a "Civil Rights Congress protest campaign.Negro and white delegations representing 7 Washington counties brought the evil of such shows forcibly to the attention of Harold Van Eaton, state director of public institutions, and Earl Lee, Supt. of the Monroe Reform School."40

After protesting and preventing the minstrel show, the CRC then won the right for Paul Robeson to sing in the Seattle Civil Auditorium in May of 1952. Robeson, the famous black singer, actor, activist, and communist, was slated to sing at a CRC fundraiser. When "certain bigoted city officials, pressured by self-appointed 'paytriots' moved to revoke the agreement, on grounds that Robeson's presence would engender racial hatred," the CRC quickly mobilized the black community, gathering support from local religious and labor leaders. The King County Democratic Convention voted 731 to 1 in support of Robeson's right to sing.41

These cultural victories, more subtle than court rulings, were ultimately indicative of a return to coalition politics among African-Americans and CP members. The degree of mobilization implied by various campaigns, and the success of well-publicized cases like Robeson's, implies a social base willing to turn out in numbers far greater than the CRC's five hundred card-carrying members. The Seattle CRC served as a channel for focusing community action, briefly bridging the widening gap between civil rights constituencies.

Defending the Civil Liberties of Communists

Critics of the CRC often charged that it was so preoccupied with the defense of Communists that it did relatively little to help African Americans. This tension between civil rights and civil liberties, blacks and reds, would concern the CRC throughout its brief history, especially the national organization. In his book _The Forging of a Black Community_ (1994), historian Quintard Taylor maintains that "Seattle ultimately proved to be the crucible for 'black and red coalition politics.'"42 And he credits the CRC as important to this coalition politics. As we have seen, black civil rights were in fact a major focus of the Seattle chapter of the CRC, but it also true that much of the chapter's energy went into defending Communists. In this endeavor the CRC stood alone. Whereas the NAACP and the CUC championed civil rights, no one was eager to defend Communists in the midst of the Red Scare. As one CRC newsletter stated,

we have refused to be drawn and quartered over the question of defending civil rights for Communists. We say that if the people of Japan, Germany and Italy had protected the civil rights of Communists, they would have beaten fascism, they would have prevented WWII and they would have saved scores of millions of lives. We make no bones about it--we will defend the civil rights of communists here in the United States. That is the most important contribution to democracy today.43

In 1948, a CRC advertisement in The New World invited others to join them: "TIRED OF GETTING PUSHED AROUND? How about getting together and fighting back? The Civil Rights Congress is an organization for Americans who believe freedom is worth fighting for. They are the people who believe with Thomas Jefferson that 'resistance to tyranny is obedience to God.'"44 Couched in the rhetoric of the constitution, this communist invitation to resist the tyranny of Cold War hysteria met with substantial support in Seattle.

In February of 1948, John Caughlan brought a case against the Washington State Supreme Court protesting the formation of the Canwell Committee. Representing John Daschbach, William Pennock, David Cochran and others, Caughlan accused legislators of illegally blocking efforts to collect signatures on a referendum that would have halted the Canwell Committee.45 Caughlan's accusation was ignored, the writ denied.

Three months later, Caughlan was indicted for perjury, accused of lying in an earlier case. _The_ _New World_ announced the formation of a "Caughlan Defense Fund" and urged its readers to contribute, reporting: "The indictment charges Caughlan with perjury in connection with his testimony in the naturalization case almost two years ago of Alex Knaisky of Seattle. The government contends that the attorney testified at that time that he was not a member of the Communist Party."46 The specifics of the perjury charge involved two sentences spoken while Caughlan was not under oath. The Seattle CRC insisted: "It is our opinion that the indictment is purely political. If it is possible to silence, even imprison, a person because he has for years given his legal services to preserve the civil rights of the people and to better their conditions in life, than the liberty of all citizens is endangered."47 The CRC rallied around Caughlan. Donations poured in from chapters across the state.

At a WPU meeting, Caughlan described his indictment as systemic, rather than personal, stating:

It is not only an attack upon me, but what is more important, it is an attack on all the progressive forces in our state to whom I have been privileged to give my legal services for many years. In fact, it is generally known that I have devoted my energies to the defense of the rights of the people, pensioners, social security recipients, the Negro people, political minorities, labor unions, the foreign born--the people who are most in need of legal services. As an attorney I have also represented the Communist Party as well as individual members to the party whose constitutional rights were violated. All of this is a matter of public record--a record of which I am proud.48

Here, Caughlan articulated a frustration that would trouble the CRC throughout its duration. The CRC felt scrutinized not because of its ideology, but because of its lack of efficacy. Testifying at the Canwell hearings, informant Sarah Keller reported Caughlan during his WPU days as a "very vicious talker," who urged pensioners to "put the heat of hell on all those reactionary legislators and put it on hot."49 Caughlan and the CRC vocalized opposition to the Canwell Committee in a political climate where silence was the modus operandi.

Caughlan's perjury charge was a serious setback for the fledgling CRC chapter. The court acquitted Caughlan in September 1948 in what was lauded by The New World as "the beginning of the end of the Canwell Committee" and "a telling blow at an entire stable of Canwell Committee 'witnesses.'"50 Once its legal arms were freed, the Seattle CRC was able to renew its assault against the Canwell Committee.

Within weeks of Caughlan's acquittal, he took on Professor Ralph Grundlach's case in the Canwell hearings at the University of Washington, fighting against the State-sponsored attempt to scout out the radicals of academe.51 The state investigated six professors, including Garland Ethel, Harold Eby, Melville Jacobs, Joseph Butterworth, Hebert Phillips, and Ralph Gundlach Three of the six professors acknowledged current or former CP membership and the other three (Eby, Phillips, Butterworth and Grundlach) had all taught classes in 1947 at the Pacific Northwest Labor School, an institution both Daschbach and Caughlan had been heavily involved in.52

While much of the public sector remained complacent and cowed in the face of communist allegations, the CRC swung into action. _The New World_ reports,

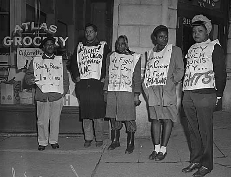

A Civil Rights Congress picket line was crossed by Rep. A.F. Canwell as he went to the speaker engagement before the Seattle Rotary Club at the Olympic Hotel. Pickets demanded abolition of the committee, called for dismissal of the charges against 12 indicted Communist Party leaders, and demanded no arms for Franco Spain. Progressive Party co-sponsored the demonstration.53

Not only did the Seattle CRC picket Canwell Committee meetings, they also continued to send petitions and collect signatures condemning the closed hearings, organizing a "2,500-strong rally on the University of Washington campus in the spring of 1949."54 Despite these efforts, three professors lost their jobs after the Canwell hearings.

However unsuccessful the protests, it is important to emphasize the importance of a vocal and unequivocal voice of dissent in the face of the Canwell Committee. In a political climate where Communist Party members were beginning to go underground, the Seattle CRC was able to publicly denounce the unconstitutionality of the Canwell investigations.

By 1949, public opinion showed increasing hostility towards communist ideology and a growing concern with fifth column infiltration. A 1949 _Seattle PI_ article entitled "Loyalty to America" insisted: "Communism should not be taught in the classrooms of the United States any more than thievery and arson and rapine are taught, for it is not only a from of criminality as vicious as any of these but worse than all of them."55 Anti-communist hyperbole continued to escalate with little opposition.

Despite ongoing frustration with closed hearings against any alleged communists, the spirits of the Seattle CRC remained high. In a January 1950 letter issued to all members of the Washington State Civil Rights Congress, John Daschbach, acting secretary announced:

The past year has seen stepped up struggles in defense of civil liberties. Important victories have been won: Dr. Phillips won acquittal from a charge of contempt of the Canwell Committee ; O'Connell and Crumply successfully defeated a charge of Disorderly Conduct for picketing the Canwell committee; Rachmiel Forschmiedt won back his post as a Seattle City Employee following his dismissal resulting from witch- hunting; and the Canwell Committee was not continued by the 1949 legislature. Nor was a single proposal by the defunct committee enacted into law. Important unfinished business faces us. Complete freedom must be won for the Seattle Five, convicted of Contempt of the Canwell Committee, who have just presented their case to the State Supreme Court. Police brutality, especially against minorities must be ended everywhere in the State, along with all forms of Jim Crow. The CRC is the first permanent organization fighting for the civil rights of the American people. We must build it stronger in members, in activity and in influence.56

In focusing on a few meaningful victories, Daschbach framed the "unfinished business" of the Seattle CRC in terms of small local battles.

For the CRC, the next few years would be characterized by seemingly endless struggles against a deluge of oppressive legislation and court cases at the state and federal level, court decisions that would back the CRC into a tight legal corner. The CRC continued to couch its rhetoric in the spirit of democracy, insisting in the _Action Bulletin_ that "American Freedom was born in the struggle to overcome a law--the Stamp Act. The American people today need to know the danger, as other Americans saw the dangers before, and then acted in unity to sweep away the dangers and restore liberty."57

There were further victories. After months of letter writing, signature drives, and law suits, the CRC overturned a state law requiring that political candidates sign a loyalty oath. The May,1952 _The Liberator_ exulted that "five leaders of the Washington State Progressive Party successfully challenged the so-called loyalty oath for political candidates set forth in . the little state McCarran Act. Thurston County Judge Wright ruled that this so called loyalty oath was unconstitutional."58 A month later the Seattle CRC begged readers to:

[Do] everything you can in defense of constitutional liberties--write letters, speak to your neighbors and shopmates, sponsor resolutions in your unions of club. every letter or card, every petition, every resolution speaking for democratic liberties and against Smith Acts, Jim Crow, McCarran Acts, and segregation will be more powerful than ever in this election year… Keep the pressure on. Make every candidate declare himself.59

This injunction to "keep the pressure on" is one the CRC followed vigilantly. In court, campaign, and committee room, the CRC aggressively pushed for a return to the constitution and its promises of equality. In defending both civil rights and civil liberties, Seattle CRC activity was a final gesture to the heyday of coalition tactics. However, despite high spirits and hard work, the effects of the Cold War would prove intractable.

Statewide Crackdown on Communism and the CRC

On September 17, 1952, a statewide crackdown on communist-affiliated leaders saw the arrests of the "Seattle Six," a move that effectively robbed the most active local civil rights organizations of their leadership. _The Liberator_ reported those arrested:

John Daschbach, State Director of the Civil Rights Congress; Karly Larsen, a founder of the CIO International Woodworkers of America, member of its international executive board.; Henry Huff, Washington State Chairman of the Communist Party and veteran of decades of struggle on behalf of labor in our state; William Pennock, Phi Beta Kappa, President of the Washington State Pension Union and former state legislator; Paul Bowen, Negro leader who helped organize and fight for FEPC and Independent Party candidate for congress in 1950; Barbra Hartle, Phi Beta Kappa and Communist women's leader; and Terry Pettus, Northwest editor of the Daily People's World.60

Attorney John Caughlan took on the case of the Seattle Six, charged with intent to overthrow the government under the Smith Act.

CRC members across the nation expressed support for the Seattle Chapter while it was under seige. In frustration, _The Liberator_ concluded that "the war makers and the Justice Department are trying.to sell the people the big lie.that says, 'all who fight for peace, for the betterment of the working people, for Negro rights, for women, for the aged and for civil rights, are the enemies of your country.'"61 Bail was set at an obscene $10,000 or $20,000 per person, which the CRC insisted was a clear violation of eighth amendment rights.62 At the height of Cold War paranoia, state incompetence and vague charges created an atmosphere of absurdity characterized in a story run by the Seattle PI:

Deputy United States marshals accidentally freed an important prisoner. John S. Daschbach, a 38 year old, 185 pound 5 foot 9-inch, round-faced alleged Communist, charged with conspiracy under the Smith Act.

He telephoned the marshal's office. Who posted his bail?

"Ah,er. Why no one did," he was told.

"Has there been a mistake made, then?," Daschbach asked.

"Indeed," was the reply.

"What shall I do?"

"Please come back."

Daschbach did. 63

Daschbach later said: "the one thing the Justice Department has done in these Washington Smith Act cases is to release me on no bail, finally getting the bail to match the evidence."64

The local CRC chapters struggled to raise bail for their leaders and still carry out the goals of the organization. Daschbach's wife Marjory Daschbach, with the aid of Harriet Pierce, secretary of the Smith Act Appeal Committee of Seattle's CRC, set up fundraisers for their bail. By November of 1953, all but Daschbach and Barbara Hartle had been released. However, the Seattle chapter of the CRC disintegrated as Cold War pressure mounted.

Another tragedy resulting from the Seattle Six trial was the suicide of William Pennock. After admitting to CP membership during the trial, he died from an overdose of sleeping pills in August 1953. Over one thousand people attended the funeral of the longtime CP member, WPU president, and activist.65 Of his membership in the party, Pennock had stated: "It was the Communists who gave the most energetic, effective, fearless leadership, in fighting, not for socialism but. for the immediate, concrete essentials of existence for the people under capitalism."66

The Seattle Six, charged as Communist dissidents, were some of the most important labor and civil rights activist leaders in Washington State. Without the cohesion and energy Daschbach brought to his work, the local CRC floundered. Signature counts dwindled as affiliation with the besieged chapter became more and more dangerous.

Dissolution

The situation in Seattle read like a litmus test for the rest of the country. By the mid-1950s, the CRC was spending its funds in expensive court case battles, to protect their leaders from the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) investigations and allegations of tax fraud.67 At the national Civil Rights Congress Convention in New York, in December 1955, the CRC passed a resolution to dissolve the CRC as an organization. The resolution read:

Whereas, as a result of the successes of its legal and education and organizing activities the reactionary forces in government have intensified their legal persecution of Civil Rights Congress, utilizing and abusing the powers of the Department of Justice. Whereas the intensification of the fight against these attacks would absorb the efforts, energies and funds of large numbers of people, thus diverting these forces from the growing broadest offensive against reaction in general, against the McCarran Act, Smith Act and sedition acts, against the current Dixiecrat genocidal attacks on the Negro People, and for the restoration of the constitutional liberties and the bill of rights for all. the Civil Rights Congress is hereby resolved.68

Seattle was the only chapter to vote against dissolution. General sentiment seemed to validate the need to distance the civil rights movement from the civil liberties movement. In the coming decade, the more singularly-aimed civil rights movements achieved more success than the coalition movements of the late forties and early fifties.

A victim of McCarthyism and the hysteria of the Cold War communist scare, the national CRC disbanded in 1955. The dissolution of the Seattle chapter ended one of the most focused CRC groups in the nation. During its seven active years, the Seattle CRC maintained an active voice of dissent in an era of uneasy quiet on the subject of civil rights and liberties. In a re-assertion of coalition politics made possible by the WPU, the CRC provided a means for focused community activism. Though brief, their swan song of cooperative political action achieved small but meaningful local victories and laid the groundwork for subsequent civil rights activism in Seattle.

**© Copyright Lucy Burnett 2009

**HSTAA 498D Fall 2008; 499 Winter 2009

1 The Voice, 28 March 1949, pg. 8.

2 Ibid.

3 Gerald Horne, _Communist Front?" The Civil Rights Congress, 1946- 1956_ (Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press,1988), 348.

4 Quintard Taylor, _The Forging of a Black Community_ (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994), 184.

5 Richard Hobbs, _The Cayton Family Legacy: Two Generations of a Black Family, 1859-1976_ (Seattle: University of Washington, 1989), 223-300.

6 A few major studies of these organizations include: Albert Anthony Acena, "The Washington Commonwealth Federation: Reform Politics and the Popular Front," Ph.D dissertation, University of Washington, 1975; Margaret Miller, "The Left's Turn: Labor, Welfare Politics and Social Movements in Washington State, 1937-1973," Ph.D dissertation, University of Washington, 2000; Jennifer Phipps, "Washington Commonwealth Federation and Washington Pension Union" Communism in Washington State History and Memory Project:http://depts.washington.edu/labhist/cpproject/phipps.htm

7 Phipps, Chapter 4 of the "Washington Commonwealth Federation and Washington Pension Union."

8 Ibid.

9 Miller, "The Left's Turn," 79.

10 Miller, "The Left's Turn," 122-123.

11 "History of Seattle Civic Unity Committee: February 1944 to January 1952," by the Red Feather Service of Community Chest and Council for Seattle and King County.

12 The Seattle National Negro Congress would later be absorbed by the CRC. See The Seattle Civic Unity Committee, "The History of FEPC in the State of Washington," in Seattle Civic Unity Committee Records, 1938-1965, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, Box 1, Folder 1.

13 Ibid.

14 Resolution to the House No. 10.

15 Greg Lange, "Washington State Legislature Passes the Un-American Activities Bill on March 8, 1947," _History Link,_10 July 1999. Electronic edition available online at: http://www.historylink.org/ index.cfm? DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=1484.

16 "Need Rights Group, " _The_ New World, 30 September 1948, 9. A year earlier, the Washington Pension Union had begun sending copies of the national CRC Bulletin to every WPU local in the state, recommending that it be read to the membership. Also see Miller, "Left's Turn," 170.

17 Miller, "The Left's Turn," 171.

18 Ibid.,172.

19 "Affidavit and Application for Writ of Mandate," 1949, The Caughlan Papers, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, Box 4, Folder 10.

20 Ibid., 2.

21 Horne, 346.

22 "John Caughlan Video Interview," Communism in Washington State History and Memory Project, available online at: http://depts.washington.edu/labhist/cpproject/caughlan_interview.htm.

[23] John Caughlan Papers, Box 4, Folder 11.

24 Horne, 350.

25 "Minutes," Washington Pension Union Papers, May 1948, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, Box 4, Folder 4.

26 "To the Washington Congressional Delegation," 28 June 1949, John Daschbach Papers, Box 1, Folder 3.

27 _The Voice,_ Volume 6, 19 August 1948, p. 8.

28 Horne, 348.

29 John Daschbach Papers, Box 1, Folder 8.

30 Ibid.,2.

31 The Trenton Six was a case in which an all-white jury convicted six African-American defendants for the murder of an elderly white shopkeeper. In the appeal, the CP revealed trumped-up charges. See Jon Blackwell, "1948: A Cry for Justice," _The Trentonian_ [no date], electronic edition available online at: http:// www.capitalcentury.com/1948.html.

32 _The Voice,_ Volume 6, 10 November 1949, 8.

33 _The Voice,_ 17 March 1949, 9.

34 "Action Letter," 21 February 1950, Naomi Benson Papers, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, Accession 204, Box 5, Folder 11.

35 Ibid.

36 Daily People's World, 4 May 1951.

37 Micah Ellison, "The Local 7/ Local 37 Story: Filipino American Cannery Unionism in Seattle 1940-1959," http://depts.washington.edu /civilr/local_7.htm

38 Action Bulletin, 12 February 1951, Naomi Benson Papers, Box 5, Folder 10.

39 _The Washington Liberator,_ February 1952, Naomi Benson Papers, Box 5, Folder 11.

40 Ibid.

41 _The Washington Liberator,_ May 1952, Naomi Benson Papers, Box 5, Folder 5-10.

42 Taylor, 184.

43 "CRC Newsletter," 18 August 1949, John Daschbach Papers, Box 1, Folder 21.

44 The New World, 4 November 1948, p. 7.

45 _The New World,_ 26 February 1948, p. 3.

46 Ibid.

47 "CRC Defends Caughlan," _The New World,_ 13 May 1948, p. 3.

48 Ibid.

49 UNAMERICAN Activities Committee--Canwell Hearings 1948, Report of Joint Fact Finding Committee on Un-American Activities, Established by the Thirtieth Legislature under House Concurrent Resolution No. 1, p. 505.

50 _The New World,_ 30 September 1948, p. 1, 4.

51 For more on the Canwell hearing, see "The Canwell UnAmerican Activities Hearings and Mark Jenkins' All Powers Necessary and Convenient," Communism in Washington State History and Memory Project, available online at: http://depts. washington.edu/labhist/cpproject/allpowers.htm.

52 "Communist Activities in the Seattle, Washington, Area," Hearings, House of Representatives Part I, "Pacific Northwest Labor School Pamphlet," 1955.

53 _The New World,_ 21 October 1948, p. 2.

54 Horne, 351.

55 "Loyalty to America," _Seattle Post Intelligencer,_ 21 February 1949, John Daschbach Papers, Box 2, Folder 3.

56 Naomi Benson Papers, Box 5, Folder 5-10.

57 Action Bulletin, 19 October 1950, Naomi Benson Papers, Box 5, Folder 5-10.

58 Ibid.

59 The Washington Liberator, November 1950, Naomi Benson Papers, Box 5, Folder 5-10.

60 Hartle would later testify against the others in an effort to lighten her sentence. The Washington Liberator, September 1952, Naomi Benson Papers, Box 5, Folder 10.

61 Ibid.

62 Ibid.

63 "'Please come back to Jail:' Marshal's Aid Asks in Red Suspect Freed in Error," The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 20 September 1952.

[64] _The Washington Liberator,_ September 1952, Naomi Benson Papers, Box 5, Folder 10.

65 Horne, 353.

[66] Miller, "The Left's Turn," 66-67.

67 Ibid., 357.

[68] "Resolution of Dissolution of the Civil Rights Congress," John Daschbach Papers, Box 1, Folder 1.