The Filipino American-led cannery workers union has a marked history of conflict and tumult, from the assassination of the president Virgil Duyungan and secretary Aurelio Simon in the mid-19361 to another dual assassination of union leaders Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes in 19812. Historians have concentrated on the events and issues surrounding the two sets of assassinations, providing valuable accounts of union building in the 1930s and of the reform efforts initiated by Domingo and Viernes forty years later, but we know little about the intervening decades. This essay uses union records to explore the critical middle period in the history of Seattle’s Cannery and Farm Labor Union, affiliated in the early 1940s as Local 7 UCAPAWA and after 1950 as Local 37 ILWU.

During this period, the union dealt with a myriad of struggles. Political strife and leadership shifts dominated the 1940s. As the decade waned and the 1950s began, allegations of Communist activity took a heavy toll on the union, leading to reorganization under a new national and a new name: ILWU Local 37. Recovery from these events led to a stability of power that lasted throughout the 1950s but ultimately led to a less active union.

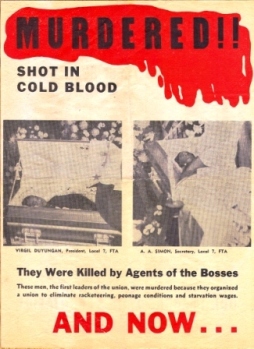

The cannery workers’ union was originally founded as the Cannery Workers’ and Farm Laborers’ Union (CWFLU) Local 18257 under the American Federation of Labor (AFL). From its birth, it was already rocked by conflict; in 1936, two of its leaders, Aurelio Simon and Virgil Duyungan, were shot and killed (presumably due to opposition from anti-union labor contractors). In 1937 the union left the AFL in favor of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) becoming United Cannery, Agricultural, Packinghouse, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA) Local 7. The local’s maturation into a powerful bargaining force was characterized by a constantly shifting leadership with a wide range of political beliefs. (The early history is covered in Crystal Fresco's essay "Cannery Worker's and Farm Laborers' Union 1933-39: Their Strength in Unity")

Wartime Challenges

The outbreak of World War II provided both opportunities and challenges for the young labor union. Membership declined as former cannery workers enlisted or took more stable jobs in defense industries. Internal disagreements seemed also for a time to threaten the union. But a new set of leaders and the intense bonds between the union and Filipino communities on the West Coast helped the union consolidate its position. By the war’s end Local 7 not only represented Seattle workers but had become the bargaining agent for cannery workers up and down the coast.

Struggles over leadership dominated the early years of the 1940s. In 1940 Vincent Navea won the election as President of Local 7. Navea’s past gave him a tenuous hold on the presidential office: he was respected as a hard-working union official (he had previously been the union’s business agent) and upstanding community member, but he had never worked in the canneries. A great deal of conflict and intrigue surrounded Navea, as his strong business sense was accompanied by constant accusations of being a “company man.” These accusations were supported by his personal history. He had previously worked for the Western Outfitting Company, which appears to have been associated with the pre-union labor contractors.3

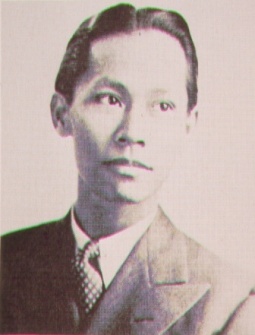

Navea’s successor, Trinidad Rojo, was elected President of Local 7 in October 1942. Wordy, intellectual, and often less than humble, he was active in union affairs from the 1940s through the 1950s. Rojo espoused efficiency and discipline in the union. In a 1975 interview he took credit for a series of innovations and reforms, such as introducing the time clock to the office, reducing gambling problems and concentrating the flow of union money in the offices of the treasurer and secretary.4

Like many young Filipino men, Rojo came to the United States in search of educational opportunities. In the Philippines high school was very expensive and it was not uncommon for a full family to spend a large amount of its resources to educate one child.5 The United States – to which Filipinos could immigrate freely until the passing of the Tydings-McDuffie Act in 1934 – offered young Filipinos the chance to be self-supporting students, taking a great weight off of their families. However, many found that after gaining an education there were few opportunities for Filipinos in America. This frustration led many highly educated individuals to become active in labor struggles. Rojo was one of them.

Rojo had succeeded Navea in 1942 but there was continuing conflict between the two men and their allies. In August 1943 an election dispute occurred relating to the validity of the nomination of Irineo Cabatit for the local’s annual presidential election. Membership meeting minutes show two distinct groups: one composed of Navea and Cabatit, and another led by Rojo and the secretary, Prudencio Mori. Cabatit had withdrawn from the election over the phone but still wanted to run for president. Arguing that votes should be thrown out because he was removed from the ballot, and that it was constitutionally required for withdrawals to be submitted in writing (and not over the phone), Cabatit was still given a chance to run as president for the remainder of the voting period.6 He did not win the presidency.

Following Cabatit’s defeat, Navea attempted to gain control of the union membership from the outside by filing a petition to the War Labor Board asking that the American Legion post that he headed (Rizal Post), be recognized as the sole bargaining agent to the Alaska cannery industry.7 Most of the canneries had been consolidated under one umbrella organization during the beginning of the war and they relied on the union to seasonally dispatch workers to Alaska for the two-month summer canning season. Thus, winning representation with the industry was the key to controlling the cannery labor base. Navea was unsuccessful and was charged with anti-union activities by the union. A small 1944 membership meeting vote on the matter revealed how split the membership was at the time: 38 voted him guilty while 32 voted him not guilty.8 The leadership was much different, however: an 8-1 vote by secret ballot in an executive board meeting two days earlier condemned Navea to a ten-year suspension.9

Consolidation

One can see by the small vote tally that the union membership decreased dramatically during the war. Between the dramatic fall of Bataan to the Japanese in April 1942, the draft, and the lure of non-seasonal work, the UCAPAWA locals lost over a thousand workers to various military services and even more to industries related to military production.10 The labor shortage had a drastic effect on the union and the salmon industry in general. The government exempted many Filipino workers from the draft because the supply of canned food was considered important to the war effort.

Faced with this challenge, Local 7 looked towards new fronts on which to represent workers. Alaska cannery workers shipped out of Portland and San Francisco as well as Seattle, and in those ports they were represented by affiliated unions: Local 5 in San Francisco and Local 266 in Portland, both of which dispatched predominantly Filipino workers to Alaska under the same agreed-upon contracts. According to various oral histories, Local 7 had the most sway with the UCAPAWA International. Since the union was in charge of dispatching, it also became heavily involved in the process of labor recruiting during the war, sending agents to Filipino communities around the west coast to get more workers. The Filipino community in Stockton, California was one of the most looked-on targets. By the summer of 1944, there was talk of setting up a year-round branch in Stockton and Local 7 President Rojo himself was asked to travel there to drum up more support.11 Even after war, when the labor shortage was dramatically ended, Stockton continued to remain an important to Local 7’s leaders and members, largely because the seasonal nature of Alaska cannery work fit well with the asparagus season in California.

As the union expanded outward in search of new members, it consolidated its three locals into the one Seattle-based Local 7 based on the argument that it was redundant to have three organizations negotiating with the single Alaska Salmon Industry organization. The level of hostility from the small southern locals to consolidation is difficult to gauge, as their own records no longer exist. Local 266 in Portland fought not for continued existence as a separate local but did demand the continued operation of the office. Upon hearing that the two southern locals were going to be absorbed by the Seattle one, the Portland local’s president Ernesto Mangaoang traveled to Seattle to request only that the Portland union hall retain some funding, explaining that it was an important community center. In the discussion, Rojo spoke up “not as president, but as one who has studied the problems of Filipinos in the United States” and made Local 266 a branch of Local 7. The Seattle local also killed two birds with one stone by mandating that the Portland branch officers must spend several months out of the year organizing labor in Stockton.12

The intersection of labor interests with Filipino community interests was not uncommon in this union. While it did cater to some other Asian-American interests (such as establishing a “Farm Committee” to aid interned Japanese-American farmers in holding their land for no profit13), it was becoming more and more a Filipino union. The Chinese-American populations in Portland and San Francisco lost power from the consolidation of the three locals and the Japanese Americans on the west coast lost all representation due to internment.14 While Filipinos had dominated the union since the beginning, the war-era dramatically eroded the role of other Asian Americans. .

By and large, the union and the Filipino community benefited from one another. Local 7 was considered the most militant and active Filipino union in the United States. Despite a large Filipino population that was dispersed throughout both the urban and rural Pacific coast, Local 7 was seen as the one place during the summer months where Filipinos in America could get a job en masse outside of farm work. Perhaps the most memorable photos of the union’s history are those of Main Street in Seattle, showing a massive crowd of Filipino men waiting outside the union hall to be dispatched. It would be incorrect to argue that the union was the sole community center. Fraternities such as the Caballeros de Dimas Alang and umbrella groups like Filipino Community of Seattle, Inc. held massive community events as early as the mid-1920s and continued to do so at least through the 1950s.15 However, the union hall was still a valuable tool for the Filipino community, between annual dances, various social functions, and, of course, the employment it promised.

Cold War Tensions

Communists had been involved in the union from its beginnings in the 1930s. As the Second World War ended and the Cold War began, the presence of Communists in the leadership of the union would usher in a decade of volatility. However, unlike many unions with Communist Party ties, the Cannery Workers Union would not be destroyed or severely weakened by outside forces.

The early postwar years saw continued intra-union political strife that led to the creation of a rival union. Immediately following the end of the war, the union was characterized by dull union meetings and a highly unsuccessful 1946 strike under the presidency of Prudencio Mori.16 Trinidad Rojo had left at the war’s end to resume his studies but was back by 1947 to witness (though not really participate in) a tense split in political differences between “the conservatives and the progressive”17 at Local 7 (now Local 7 of the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers Union of America, which replaced UCAPAWA that year). The “progressive” side (including Mori) accused some members of the union leadership of being associated with the canning industry while allegations of communism were already being prepared by the more “conservative” side. In early 1947, during one of the heated arguments resulting from this conflict, Max Gonzales, the vice president of the union and a staunch anti-Communist, pulled out a revolver and shot in the “general direction” of the more leftist Matias Lagunilla,18 who would later become a secretary at the union. The minutes of that particular meeting have disappeared, so it is difficult to ascertain what exactly catalyzed the shooting. The political divisions between Gonzales and Lagunilla were certainly apparent, however, and would be a disruptive issue for some time.

While Gonzales did not hurt anyone, he still submitted his resignation to the Executive Council three days later. It was rejected by Mori and the rest of the council on the grounds that Gonzales’ resignation would signify an undesirable lack of unity among the union. The Executive Board minutes also go on to exemplify Gonzales’ “excellent track record” of service for the union,19 but this added discussion appears to have taken place primarily to make the choice appear less political.

In early March, 1947 the FTA International’s president, Donald Henderson, came to Seattle and met with Local 7’s officers. He was not well-received. Stating that members were fearful of going to meetings because of Gonzales’ actions, Henderson sternly chastised the officers:

This Executive Council has not lifted its finger to condemn such an action to protect its members. You are violating your oath and office by not acting on this matter. You are giving the C.I.O. a black eye for refusing to act on this matter. You are also giving the Filipino people a black eye.20

In spite of Henderson’s condemnations, the council tabled the motion to expel Gonzales. By mid-June, he was still an active member in the council and, with the support of fellow officer Cornelio Briones, was trying to move Local 7 in the direction of secession from the Communist-linked FTA International. Mori was in staunch opposition, arguing that the International was vital to the union’s success. Gonzales was convinced that Local 7’s defiance against the International would result in Local 7’s charter being revoked.21Local 7 remained intact, however; instead of its dissolution, Gonzales was expelled and Briones followed him.

Gonzales and Briones then formed the independent Seafood Workers Union. They filed a suit against Local 7 in an attempt to dissolve it.22 During the court proceedings, the Local 7 leadership was held in contempt of court for failing to produce documents relating to alleged misuse of $6,000 from the union’s burial fund (this fund came from annual payments from members and was to be used to pay for a funeral in the case of a worker’s death).23 The contempt ruling effectively tied up the union’s treasury, making it difficult for Local 7 to apply its budget towards being effective against the cannery industry. However, the majority of the Filipino community and the workers remained with Local 7 and the case was decided in its favor in what Trinidad Rojo called a “technical knockout.” It turned out that Gonzales was working as a cannery foreman, thus making his Seafood Workers Union a company union and therefore illegal.24

Not long after the Gonzales challenge was resolved, another factional divide emerged between newly re-elected President Rojo, who positioned himself as a noncommunist moderate, and leftwing activist Chris Mensalvas. The issue was not radicalism but how to allocate resources and time. In 1949 Mensalvas would defeat Rojo and become President of the local, remaining in that office until 1959. Mensalvas was a newcomer to Seattle, having been initially involved in labor struggles in other areas of the Pacific Coast. He spent most of his early years in the United States going to school and working on farms, where he was exposed to Communism and involved himself in labor activism. He eventually became the business agent of the Portland cannery local before the locals merged.25 Due to his resistance against some amalgamation procedures, he resigned largely at the bidding of Gonzales and Briones26 only to resume involvement in union affairs upon returning to the Portland branch. After the death of his first wife in 1947, he became involved in the Seattle local as the publicity director but still had a marked interest in California. In late 1948, he left Seattle and moved to Stockton, where he served as a publicity director during attempts to organize asparagus workers. That effort ended in defeated and costly strike. (costly because of the civil and criminal cases that followe).27 Rojo later wrote that Mensalvas and those working with him spent an exorbitant amount of money (“The legal fees alone cost over $37,000”) for the strike despite Rojo’s warnings that it would fail.28It is difficult to ascertain how accurate Rojo’s report on Mensalvas is since there is little documentary evidence to corroborate it; on the contrary, letters from Mensalvas to the Local 7 Seattle headquarters in April 1949 indicate that some significant progress was made in Stockton.29 Whatever the case was, Rojo and Mensalvas never appeared to be on good terms with one another.

Confronting the Taft-Hartley Act

The inter-union strife was further complicated by the effects of the Taft-Hartley Act (also known as the Labor-Management Relations Act), passed in 1947 to outlaw closed shops and require union leaders to file affidavits declaring that they were not members of the Communist Party. While the union and its leadership did not publicly declare any sort of Communist affiliation, it was well-known within the community that Communist Party members had long been active in the politics of Local 7. According to Rojo, it was not uncommon for right-wing members of the politically diverse Filipino community to report alleged Communists to the Bureau of Immigration.30 With this new set of anti-Communist legislation, these reports became a major concern for the leftist union leadership.

The Seafood Workers Union merged with the Alaska Fish Cannery Workers (AFCW) of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and made another attempt to undermine the union… This amalgamated organization petitioned the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) for representation elections, which were subsequently approved and set for April of 1949. Local 7 was accused of being a Communist union, and the election was preceded by a raid from U.S. Immigration officials who arrested business agent Ernesto Mangaoang, newly-elected president Chris Mensalvas, and several others on accusations of being Communist.31

While Local 7 sustained the attacks quite well from an organizational standpoint-- winning the representation election in 1949,--the specter of Communist involvement haunted the union for the next decade. Later that year the FTA International was expelled by the CIO because of its ties to the Communist Party. That led to yet another attempt by conservative cannery workers to change the course of Local 7. Several Local 7 officers resigned and formed a “red-free” union, Local 77, UPAWA-CIO, under Vincent Navea,32who had been president of Local 7 ten years earlier.

Local 7 then gave up its affiliation with the wounded Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers Union of America, finding a new parent international union in the International Longshoremen and Warehousemen Union (ILWU). On March 26, 1950 the cannery workers affiliated with the ILWU and became Local 7-C. That summer, it won collective bargaining rights in another NLRB representative election , defeating Local 77 and the Alaska Fish Cannery Workers’ Union, SIU-AFL. The following year, Local 7-C signed a four year union shop contract with the canning industry and subsequently became Local 37 ILWU.33

Why did Local 7 succeed against these competing unions despite the constant threat of Communist accusations? One important factor is that Local 7 had the power of the union hall. In mid-1948, when Gonzales’ and Briones’ aggression was at its peak and the new Taft-Hartley law was in effect, attendance at May membership meetings was as high as 560 people.34 Meetings in 1949 were not as large but still reached almost 300 members near the end of May,35 right before the beginning of the dispatching season. This was a significant number out of a yearly dispatched force of several thousand workers, and it was exposed much more to Local 7’s leadership than it was to the voice of the opposition. Moreover, Local 7’s leaders still participated in community activities and were allowed to stand their ground and defend themselves in open letters, public discussions, and so on. While many community members whispered about rumors of Communism among the union leaders, the workers were still more familiar with Local 7’s leaders and unfalteringly supported them in NLRB elections.

Facing the Threat of Deportation

After 1950, the threat of breakaway unions and outside unions would recede. After affiliating with ILWU and becoming Local 37 some of the turmoil diminished, but the union and its leaders faced a new set of problems. On November 17, 1949 Ernesto Mangaoang was arrested and held for deportion under the order of District Director John P. Boyd (who would antagonize the union over this issue for some time) . He was released eleven days later under a ruling by the District Court that Boyd’s action was an abuse of discretion, but Mangaoang’s problems and the union’s problems were far from over. Deportation orders and court cases would dominate the next several years.36

In 1950, Congress passed the McCarran Internal Security Act), requiring communists and communist front organizations to register with the Attorney General and allowing immigration officials to make a case to deport “subversive” aliens. Under this act, Mangaoang and some thirty other Filipinos were placed in jail. Mangaoang’s attorneys were not notified so he was not allowed to cross-examine his witnesses. After 83 days jail, he was released, and a deportation order soon followed. The case worked its way up to the Supreme Court in 1953 and was concluded by an issue brought up by the famous defense attorney John Caughlan, who argued that Mangaoang never technically “entered” America as an alien because he traveled from the Philippines while it was still an American territory.37 This landmark ruling established residency rights for the thousands of Filipino Americans that had arrived before the Philippines established its independence in the mid-1930s.

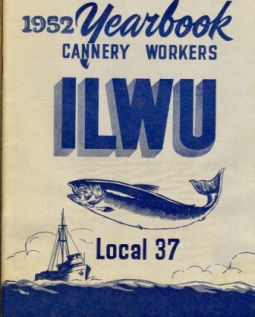

It can be argued that the intensity and strife created by the controversy over Communism and the hearings actually contributed to the union’s power and activity. Up until the mid-1950s, leaflets and publications by the union convey a strong sense of urgency to be involved and stand up for the union. During the initial arrests in 1949, Matias Lagunilla formed the Local 7 Defense Committee and released a large flier (click here) with pictures of five leaders facing deportation (including Mensalvas and Mangaoang). It proclaimed in bold text, “THEY TRY TO KILL OUR UNION”, juxtaposing the Communist trials with the murders of Duyungan and Simon in 1936. The first page ends with “YOU’RE NEXT, UNLESS…” followed by the top of the second page: “…YOU HALT THIS DRIVE AGAINST OUR UNIONS.”38 These sentiments were also exemplified in Local 37’s 1952 yearbook, wrought with powerful language. Headlines implore workers to “Know Your Rights” while various articles by the union leadership espouse a very victorious and tenacious approach to the union’s recent history, especially in relation to the deportation issues.39

The union also actively lobbied against deportation legislation and anything related to it. In early 1953, Local 37 filed for an injunction on the Walter-McCarran Act with strong support of the membership.40 The local also educated its members on the effects of the immigration laws through news bulletins.41 The International also provided some assistance by meeting with immigration officials,42 but the record provides little evidence of monetary assistance.

The newly renamed Local 37 found itself identifying strongly with the ILWU International. As the ILWU president Harry Bridges faced deportation and prison, parallels were drawn between him and Local 37’s own Ernesto Mangaoang. The local donated money out of its general budget for Bridges’ defense, promoted his cause in its publications, and even sold “Harry Bridges Defense Stamps” to raise money.43 However, there was little the ILWU could do for Local 37, and many of the members felt that they were not getting what they deserved from the International. One issue of particular importance to the executive council was that five months of dues had to be paid to the International per year despite the fact that Local 37’s members only worked a two month season. Although leaders of other locals involved in seasonal work were brought in to explain why they were willing to pay the same amount of dues, it remained a sore spot for Local 37.44

Dissention in the Board

Throughout the 1940s and early 1950s, Ernesto Mangaoang was a hero to the union. Respected as an incredibly shrewd negotiator, he was defended by the union all the way up to the Supreme Court. Yet in the fall of 1954, not long after winning his case, Mangaoang was ousted from the union. The events that lead to this political intrigue resulted from a general dissatisfaction in the leadership of Mensalvas and Lagunilla and the involvement of the well-known Filipino author and activist, Carlos Bulosan.

Bulosan came to the United States at the onset of the Great Depression to look for opportunities outside of his agrarian community. He wrote the best-selling pseudo-autobiographical novel America is in the Heart and published it as World War II began. He was well recognized as the premier Filipino-American writer and befriended Chris Mensalvas while Mensalvas was attempting to organize labor in California. In 1952, Mensalvas invited Bulosan up to Seattle to edit Local 37’s yearbook, which remains one of the most coveted pieces of the local’s history from this time period, and would have a profoundly inspirational effect on the activist student unionists in the 1970s45. The yearbook (which is reprinted in its entirety on this site) was significant not only because of Bulosan’s involvement, but also because it was published at a turning point in the union’s history: after the inter-union competition had been quelled and a string of victories had been won against government forces despite the Taft-Hartley and Walter-McCarran acts. As liberal organizations around the nation were disappearing or morphing into something more conservative, ILWU Local 37 celebrated its leftist commitments unabashedly in this yearbook, promoting strong positions against the Korean War, the “fascist” Walter-McCarran Act, and the “stooges” in the less liberal AFL.

However, behind this celebration of the union’s militancy was a growing discontent among the more moderate members. Trinidad Rojo, who was still active in the council as a trustee, attacked Mensalvas in August 1953 for improperly using union money as president instead of confining all monetary transfers to the office of the treasurer. Mensalvas had loaned union money to Bulosan and had not been paid back. Bulosan had chronic health issues and was hospitalized at the time. Defending him with Mensalvas was Matias Lagunilla, who stated that “an injury to one is an injury to all.” Mangaoang, still Business Agent, also came to his side, trying to use a technicality to show that Bulosan owed nothing. Rojo responded in his usually analogical manner by arguing “that is like stretching a fly to cover an elephant.”46 Between the costs of all the legal defenses, the strain the local had undergone fighting other unions and the lack of support from the ILWU International, Local 37 was very low on money and every dollar became an issue.

Rojo pinned the budget problems on the leftist leadership. In November, he wrote a resolution to call in the ILWU International to investigate and audit Local 37’s leadership. In a board meeting, Mensalvas stated that “with all its good intentions, the resolution will confuse the membership; and it will make a wedge for them to come and again inject dissension.” The executive board promptly condemned the resolution. Mangaoang, however, disagreed, arguing that it is dangerous for the officers of a democratic union to refuse to be publicly investigated. Lagunilla countered with his belief that the resolution had ulterior motives and was a “dirty way of eliminating officers that they cannot eliminate in the election.”47

By 1954, Mangaoang was in open disagreement with the other Local 37 officers. In a February membership meeting, he tried to read a speech on his stance and was promptly denied the floor by Mensalvas, who said that the reading of a minority opinion at a membership meeting was unprecedented (which was most certainly untrue).48 Mangaoang prepared a leaflet stating his problems with the union leadership (mainly with their lack of activity and proper budgeting) and was challenged by the executive council at the April meeting. The conflict is exemplified in the meeting’s minutes, prepared by the argumentative secretary Matt Lagunilla:

Lagunilla said that the Business Agent is like the monkey who said to the turtle that his tail is very long; yet the Business Agent failed to look back and see if he has any tail at all. He said that we have nothing to do here all winter, but getting drunk and solving the crossword puzzle. What is wrong with solving the puzzle if there is nothing to do. Drinking after office hours is not the business of anybody, much less the Business Agent he said. He fails to include in his leaflet that he stayed in the Casino all winter playing rummy, coming only to the office to claim his weekly check. No wonder the Business Agent has so many claims not settled. Now the Business Agent resort to arbitration which means the expenditure of a lot of money.49

The next day, Mangaoang finally had the chance to speak in a membership meeting on the topic, probably because his leaflet had already been well-circulated among the membership. The same arguments were expressed and hashed out. Directly following that Mensalvas called for the nomination of officers for the upcoming election. Mangaoang’s name did not appear in any category.50

A trial committee was formed among the membership to address the allegations about both Mangaoang (for creating dissension) and the other officers of Local 37. At the June meeting as the committee began presenting findings and resolutions, matters became so heated that members were shouting at one another and came close to exchanging blows…51

The International was ultimately kept out of Local 37 affairs, however, and Mangaoang was gone by autumn of that year. In the following January, the Trial Committee presented its findings, with Mangaoang found guilty and all other cases dropped.52 The Mensalvas faction had won out entirely.

Financial Problems

Regardless of whether Mensalvas and his cohorts were guilty of acting irresponsibly with the budget, the union was still having financial difficulties. It was constantly digging into the burial fund, taking out loans of five or six thousand dollars at a time. At the July 1954 meeting it was announced that the budget had a deficit of around $15,000.53 The union also received notice from the office of John Caughlan, who had represented Mensalvas and Mangaoang when they were under threat of deportation, that Mensalvas’ $5,000 bail had finally been refunded to the attorneys but would not be returned to the union until the attorneys themselves were paid by the union. A resolution was passed in a February membership meeting stating that the local did not make any commitment to pay and the money should be returned in full.54 By March, the executive council was mortgaging the union building because it was still in the red despite having already borrowed $15,000 from the burial fund.55The conflict with Caughlan was drawn out for the next few years as the union continued to borrow money. Another eighteen thousand dollars was borrowed from the burial fund in December 1956 as Mensalvas reported that only $700 of his $5000 bail had been refunded.56 Caughlan’s case against the union eventually reached the state Supreme Court in 1958, which affirmed that the union still owed money to the lawyers.57

Local 37’s records from 1957 are missing, and records from 1958 are very spotty; however, the records that remain point to some resolution, or at least a leveling out, of the budget crisis. The minutes that remain of the executive board meetings focus more on union involvement in community events than on the financial issues that dominated the mid-50s discussions.

While membership meeting records are spotty throughout the 1950s, a look at the member attendance for various 1955 meetings reveals only 134 members attending before the peak of the dispatching for the season.58 While there may be other factors involved (perhaps the dispatching became more staggered that year), the numbers still point to a less active membership.

A New Conservative Era

In 1959, Mensalvas went to Canada to meet with the Soviets at a labor conference. On the way back, the Department of Immigration challenged his return to the country, arguing that he lacked U.S. citizenship. He somehow made it to Seattle with the aid of his attorney, but then quickly left to Hawaii and stayed there for several years. The details of his departure are unclear. Years later when interviewed for an oral history, Mensalvas briefly touched on this part of his life, saying that the “political question” in Seattle affected his decision to go to Hawaii.59 What he meant by “political question” is not clear though this time was marked by a distinct change in organizational structure, which may have been what Mensalvas was referring to. The union had moved to consolidate the offices of the president and the business agent into one. Gene Navarro, who had been the business agent since Mangaoang’s departure, had become president by Mensalvas’ return to Seattle in 1963. Navarro would remain in office with a more moderate, or even conservative, ideology that would last until the 1980s.

Why Navarro and not Lagunilla or another individual closer to the political orientation of Mensalvas? Why, after years of staving off anticommunist assaults, did the union chose a more conservative leadership so late, in 1960? The records do not provide a clear answer. Perhaps Gene Navarro was simply in the right place at the right time to maneuver for a more powerful position. What few records of meetings or elections in 1960 remain discuss little more than day-to-day business, so it is difficult to tell.

Whatever the case, the Mensalvas era ended with this single event. Mensalvas would continue to play an advisory role to the union until his death in 197860, but he did not make significant direct contributions to union activity after 1959.

The Question of Stability

It is difficult to ascertain why Mensalvas was able to remain president of the local throughout the entirety of the 1950s. It is not uncommon to draw connections in labor history between Communist elements of a union and heightened participation among rank and file members. But once Mensalvas had established his power, the membership became less active, not more. This lack of activity may have kept him in power, but may have ultimately undermined the support he needed to sustain his progressive leadership agenda.

One might also argue that the stability of Mensalvas’ power lay in the fact that the union’s conflicts were less glamorous in the 1950s than in the 1940s. All CIO locals had to deal with the Taft-Hartley law and there was a sense that everyone was in it together. Moreover, Mensalvas was able to use the dissent caused by fighting with the Gonzales/Briones faction and, later, the “red-free” Navea faction, to portray himself as a hero who used his skilled oratory to stand up against the “AFL stooges.” The conflicts of the 1950s were dirty, and generated political controversy over Communist allegations and the heated personal dissension between old friends like Mensalvas and Mangaoang. Following 1952, union survival was no longer in doubt, and these struggles lost their life-and-death tone.

Conclusion

Local 37 was not a massive union, nor was it a very well-known union outside of the Filipino community at this time. ILWU histories pay little attention to it in comparison to other locals and its successes during this era are generally not celebrated in labor history. However, it was extremely significant to Filipino Americans in an era when discrimination prevented them access to most other jobs. Equal opportunity employment would not become government policy until the 1960s, but the labor union prevailed as a source of employment for the disenfranchised Filipino Americans for decades before that, The cannery union also played a very important role in the economics, politics, and social dynamics of the Seattle Filipino community, and beyond that the Filipino American community as a whole. The tone of its struggles, from the manner in which it settled infighting to its unique successes against Communist allegations, reveals a union solidified by ethnic identity. In contrast to the rest of American society, one’s status as Filipino American was an advantage in this organization, and it fostered a Filipino American identity that would be celebrated for decades to come in both Filipino American and labor history.

(c) Micah Ellison 2005

micahellison@gmail.com

(HIST 498, Fall 2004)

1 See Crystal Fresco, Cannery Workers’ and Farm Laborer’s Union: Their Strength in Unity, Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project website, also, Dorothy Fujita-Rony, American Workers, Colonial Power: Philippine Seattle and the Transpacific West, 1919-1941 and Chris Friday, Organizing Asian American Labor: The Pacific Coast Canned-Salmon Industry, 1870-1942.

2 See Bulosan.org, The Reform Movement of Local 37: The Work of Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes,http://www.bulosan.org/html/local_37.html; also, Han et al, Unknown Heroes, http://www.arc.org/C_Lines/CLArchive/story_web01_02.html

3 “Filipinos in the Labor Front”, The Philippine Yearbook: 1941, Vincent Navea Folder at FANHS, Seattle, WA.

4 Trinidad A. Rojo, interview by Carolina Koslosky, FIL-KNG75-17ck, 18 & 19 February 1975, Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS), Seattle, WA, p. 22.

5 Many interviews from the Demonstration Project for Asian Americans (DPAA) reflect on this theme and can be found at the National Pinoy Archives at the Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS), Seattle, WA.

6 Minutes of Membership Meeting, Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers Union, Local 7, 19 August 1943, UW Special Collections, Accession #3927-1, Box 3, Folder 8. (All membership and board meeting minutes are located in this collection)

7 George A. Valdez, “A Brief History of Local 37,” 1952 Yearbook, ILWU Local 37, Chris D. Mensalvas Papers, UW Special Collections, Accession #2361-1, Box 1, Folder 14, p. 12.

8 Minutes of Membership Meeting, 5 June 1944, Box 3, Folder 9.

9 Minutes of Executive Board Meeting, 3 June 1944, Box 2, Folder 7.

10 Friday, p. 188.

11 Minutes of Membership Meeting, 29 June 1944, Box 3, Folder 9.

12 Minutes of Executive Board Meeting, 27 March 1944, Box 2, Folder 7

13 Minutes of Membership Meeting, March 1942, Box 2, Folder 4.

14 Friday, pp. 186-188.

15 Cordova, 175-183.

16 Ernesto Mangaoang, Report of the Business Agent, 1952 Yearbook, ILWU Local 37, p. 7.

17 Rojo, 21.

18 “Unionist Says He Shot To Scare,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 1947. A photocopy of this news clipping was found in the Ernesto Mangaoang folder at FANHS. Only the year was recorded on the copy, so the exact date is not known. I have tried to find the minutes of the membership meeting during which this particular event took place (in February 9) but they do not seem to exist.

19 Minutes of Executive Council Meeting, 12 Feb 1947, Box 3, Folder 11.

20 Minutes of Executive Council Meeting, 2 March 1947, Box 3, Folder 11.

21 Minutes of Executive Council Meeting, 18 June 1947, Box 3, Folder 11.

22 Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers Union (CWFLU) Local 7, “Matias Lagunilla Again a Martyr,” 1948, Local 7 UCAWAPA-CIO file, FANHS, Seattle, WA

23 “Arrest Asked for 10 Cannery Union Aids,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer 1947. A photocopy of this news clipping is on the same sheet as the previous article mentioned in the Ernesto Mangaoang folder at FANHS in Seattle, with the same lack of information as to the exact date. However, the article mentions a future court appearance scheduled for April 2, so it must have been published early in the year.

24 Trinidad Rojo, “Food Tobacco and Allied Workers of America, CIO Local 7, Now, International Longshoremen and Warehouse Union (ILWU), Local 37,” unpublished, no date (though it was written after the murders of 1981 and before Rojo’s death in the early 1990s), Cannery Workers Union Local 7, CIO folder at FANHS, Seattle, WA

25 Chris D. Mensalvas and Jesse Yambao, interview by Carolina Koslosky, FIL-KNG75-1ck, 10 & 11 February 1975, FANHS, p. 31.

26 See Minutes of Executive Council Meeting, CWFLU Local 7, 4 Feb, 4-5 Mar, 1946, Box 3, Folder 10. Some of the headings on these records are incorrectly labeled as 1947: they were transcribed from audio recordings in 1947 but their content and structure clearly show that they took place in 1946.

27 Two letters from the Chris D. Mensalvas Papers, Accession #2361-1, University of Washington Special Collections.

28 Rojo, p. 13.

29 See UW Special Collections, CWFLU Local 7, Acc #3927, Box 21, Folder 80.

30 Rojo, p. 11.

31 University of Washington Libraries Manuscripts and University Archives Division, Inventory: Cannery Workers’ and Farm Laborers’ Union, Local 7, Accession #3927, Seattle, WA, 1989.

32 University of Washington Libraries Manuscripts and University Archives Division, Inventory: Cannery Workers’ and Farm Laborers’ Union, Local 7, Accession #3927, Seattle, WA, 1989.

33 Valdez, 12.

34 Membership Meetings, Box 4, Folder 4.

35 Membership Meetings, Box 4, Folder 7.

36 Juana Mana’o (de Mangaoang), Seattle: the McCarthy Era: the Chronology, 12 June 1999, http://www.capriotti.com/lawprof/(Accessed 17 November 2004).

37 Mana’o.

38 Ernesto Mangaoang folder, FANHS, Seattle, WA.

39 The 1952 yearbook can be found both in the Chris Mensalvas Papers (Box 1, Folder 14) of the Special Collections division of the University of Washington Libraries and at FANHS.

40 Executive Board Meetings, Box 4, Folder 8.

41 See Chris D. Mensalvas Papers, UW Special Collections, Accession #2361-1, Box 1, Folder 10.

42 See Chris D. Mensalvas Papers, Box 1, Folder 3.

43 Chris Mensalvas, Local 7-C ILWU Newsletter, 7 August 1951, UW Special Collections, CWFLU Local 7, Acc #3927, Box 24, Folder 41.

44 Executive Board Meetings, 26 February 1953, Box 4, Folder 8.

45 See Bulosan.org, The Reform Movement of Local 37: The Work of Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes,http://www.bulosan.org/html/local_37.html

46 Executive Board Meeting, 7 August 1953, Box 4, Folder 8.

47 Executive Board Meeting, 5 November 1953, Box 4, Folder 8.

48 Membership Meeting, 24 February 1954, Box 5, Folder 14.

49 Executive Board Meeting, 27 April 1954, Box 4, Folder 9.

50 Membership Meeting, 28 April, 1954, Box 5, Folder 14.

51 Membership Meeting, 30 June, 1954, Box 5, Folder 14.

52 Membership Meeting, 5 January 1955, Box 5, Folder 15.

53 Executive Board Meeting, 21 July 1954, Box 4, Folder 9.

54 Membership Meeting, 9 February 1955, Box 5, Folder 15.

55 Executive Board Meeting, 2 March 1955, Box 4, Folder 10.

56 Executive Board Meeting, 11 December 1956, Box 4, Folder 10.

57 52 Wn.2d 656, John Caughlan, Respondent, v. International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union, Local No. 37-C, Appellant, Supreme Court, July 31, 1958.

58 Membership Meeting, 17 May 1955, Box 5, Folder 15.

59 Chris D. Mensalvas and Jesse Yambao, p. 57-58.

60 For a fascinating reflection of the next generation of young cannery labor activists in the 1970s, see Gene Viernes’ article “Chris Mensalvas: daring to dream” in the May 1978 issue of the International Examiner, p. 6, available in UW Special Collections, #3927, Box 36, Folder 17.