On the morning of March 8, 1970, two half-mile long columns of vehicles began forming in a south Seattle neighborhood. The vehicles moved north towards Seattle’s Magnolia neighborhood and the recently decommissioned Fort Lawton Army installation. As the convoys headed north onlookers could see the red cloth banners streaming from the antennas of the automobiles. When the caravans reached their destinations, both the north and south sides of Fort Lawton, the occupants of the cars launched a coordinated effort to occupy the fort and establish it as a cultural and social services center for Seattle’s growing Native American population. In the midst of the ensuing struggle, the occupation’s principal organizer Bernie Whitebear stated, “We, the Native Americans, reclaim the land known as Fort Lawton in the name of all American Indians by right of discovery.”1

The Native activists who invaded Fort Lawton that day were ultimately successful in their goal of establishing an urban Indian cultural center at the site. While similar centers already existed in San Francisco, Minneapolis, and New York, what was to become Daybreak Star Center was the first to be established through militant protest. This paper tells the story of the United Indians of All Tribes Foundation’s (UIATF) unique success in its battle for Daybreak Star and, in a larger sense, for what Bernie Whitebear later described as “self-determination.”2

Urban Indians and the Impetus for Invasion

The Fort Lawton invasion was a response to the declining state of Native reservations and to the challenges faced by Seattle’s growing urban Indian population, as well as the government’s apparent lack of concern for either. In this sense, the invasion was years in the making. During the 1950s the federal government began what it termed the policies of Relocation and Termination in order to deal with the “Indian Problem.” This meant that in an attempt to “liquidate all tribal assets, the federal government set up relocation programs moving thousands of Indians into cities with promises of better employment and educational opportunities.”3 It was no coincidence that the reservations identified for termination were also those with the most wealth and natural resources. According to Fort Lawton occupier and current UIATF board member Randy Lewis, the result was that “overnight the richest reservations in the country became some of the poorest counties in the country.”4

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and the Indian Health Service developed a concurrent Relocation policy that worked in tandem with the policy of Termination to deprive Natives of government services. Many Natives found that living in the stagnant economy of the reservation had become impossible without the financial aid of the federal government and so moved to cities in order to gain access to burgeoning urban economies. Seattle’s Native population rose from 700 in 1950 to more than 4,000 in 1970.5 Under its Relocation policy, the federal government encouraged Natives to migrate to cities and then ensured that once Indians left the reservation, or the reservation was terminated, they were no longer under the jurisdiction of the Tribal Governments or under the administrative authority of the BIA. In effect, Relocation nullified the federal government’s longstanding treaty obligations and further decreased its commitment to Native populations. In doing so it dramatically reduced the amount of aid the federal government was responsible for administering. Thus the government could wash its hands of Native reliance on federal programs and funding.

For Natives in Seattle, there were few places to turn for help in an often new and unfamiliar urban setting. As there were no federal, state, county, or city funds available, Natives had to rely on volunteer social services. Most of these were provided by the American Indian Women’s Service League, which operated out of an old church downtown.6 A free health care clinic also operated three nights a week in space donated by the Marine Public Health Hospital. Volunteer doctors and nurses staffed the clinic, utilizing donated pharmaceuticals stored in a lady’s restroom.7

By the late sixties, the city of Seattle was at least marginally aware of the need to address the problems of urban Indians. In 1969, the city assigned Blair Paul, a young University of Washington Law School graduate who was working as a Seattle Human Rights Department officer, to address the problem. Paul, who would become a founding member of the UIATF board of trustees, recalls that the city and the Human Rights Department hired him in an attempt to become more relevant within the widening context of the Civil Rights Movement: “It was clear that other than blacks, by the late sixties early seventies [the Civil Rights Movement] had really touched very few other minority groups.”8 War on Poverty programs meant that millions of dollars were coming into Seattle for minorities, but Indians were receiving none of these funds. Neither the Service League nor Kinatechitapi, a Native American employment assistance collective formed in 1969, were successful in securing any federal funds. As one observer stated, the city “passed the buck” while “millions of dollars poured into the Central District.”9

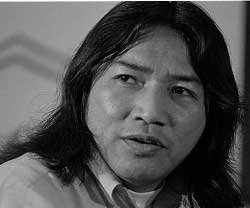

Paul felt that in order for Natives to be successful in the competition for public assistance funds floating around at the time they needed to organize. “Natives were not well organized,” he recalls. “They weren’t organized at all. I was hired by the Department to focus on the needs of urban Indians in Seattle. The first thing I did was to organize a meeting at Kinatechitapi. There were as many as sixty different Indian groups that showed up.”10 The meeting, held in September 1969, proved to be a success because it provided a forum for the emergence of new leadership. . According to Paul, that is where Bernie Whitebear began to show his abilities. “And the next two years with Bernie, it was full tilt to the wall. An amazing, amazing human being. I can’t speak highly enough of him.”11

Born Bernie Reyes in the small Eastern Washington town of Inchelium on September 27, 1937, Whitebear became aware of the problems facing urban Indians through first hand experience. He was by birth a member of the Colville Confederated Tribe, an amalgamation of eleven different Plateau bands – Colville, San Poil, Nespelem, Lakes, Southern Okanogan, Entiat, Methow, Columbia, Wenatchi, Palus, and Nez Perce – created in 1872 under executive order of President Grant. He was also half Filipino, an ethnic mix common enough that the term “Indipino” has entered the parlance of our time.12 Whitebear often had difficulty finding work and was aware of the racism that Indians faced in American cities. As a young man living in Tacoma, he fished the Puyallup River with his friend, Puyallup Native Bob Saticum. Both men were having trouble finding work and fishing was the one source of livelihood that racist hiring practices could not restrict Indians from engaging in.

In 1959 Whitebear began meeting regularly with other Natives in Tacoma, usually at Indian taverns, to discuss the problems they faced and possible solutions. The core group, consisting of Whitebear and Saticum, George Meachem, Robert Taylor, and Gary Kalapis, began referring to themselves as the “Skins.” According to Whitebear’s brother and biographer Lawney Reyes, “They spent most of their time drinking, talking, and trying to solve all the world’s needs. But Bernie knew that this was only a shallow exercise. He listened and became aware of the many problems Natives faced each day but felt it was time to move on with his life, to somehow help relieve the problems of his people instead of just talking about them.”13

In 1961 Whitebear moved to Seattle where he began organizing events to make Native concerns more visible to the White population and also creating cultural activities to help affirm traditional Native identity among urban Indians. He was aware of the political climate of Seattle during the mid to late sixties and saw it as an opportunity to press Native grievances. “Seattle had the Students of Democratic Society, the Black Panthers, United Black Contractors, Vietnam War and United Farm Workers protestors,” he wrote.14 Whitebear was not alone in thinking it was time for Native people to be more militant. At Western Washington University, Randy Lewis, also a Colville, was helping to establish the American Indian Student Union. The hosted a conference, The Right to be Indian Conference, “that drew together a lot of people from throughout the nation,” Lewis recalls. 15

On November 20, dozens of young Native American activists headed through San Francisco’s early morning fog toward the abandoned Alcatraz penitentiary and forever changed the way Native Americans would fight for their rights. Among them were a number of Northwest Natives, including Bernie Whitebear and Randy Lewis. The activists who occupied Alcatraz were for the most part young urban Indians who were either college students or recent college graduates. Their strategy was militant, confrontational, direct-action, non-violent protest. This was new in the Indian community and contrasted with the strategy of older tribal government officials, often referred to as “Uncle Tomahawks” by the new radical Indian youth, who advocated a gradualist approach and held their leadership positions through a perceived cozying up to non-Indian officials. The youth felt that they were being misrepresented by traditional leaders, and for the first time utilized their voices and stood in numbers behind such spokesmen as Clyde Warrior, who in testimony before the President’s Advisory Commission on Rural Poverty in 1967 illustrated the dissatisfaction of Indian youth: “We are not free. We do not make choices. Our choices are made for us; we are the poor. For those of us who live on reservations these choices and decisions are made by federal administrators, bureaucrats, and their ‘yes men,’ euphemistically called tribal governments.”16

The Alcatraz occupation lasted nearly eighteen months and was ultimately joined by over five thousand protesters. The young activists succeeded in capturing the attention of the national media and spotlighting the plight of urban Indians. Their ultimate goal was to establish a Native American university and cultural center on Alcatraz Island. Although unsuccessful in this regard, their methods influenced and inspired discontented and frustrated urban Indians around the country, including Seattle.

Whitebear returned from Alcatraz with an even stronger awareness of the need for a new, more radical approach in Seattle. This awareness was catalyzed in 1970 when Richard Nixon signed a bill into law, introduced by Washington Senators Henry Jackson and Warren G. Magnuson, which enabled non-federal entities to obtain surplus federal lands for 0-50 percent of fair market value.17 Under the new law, the city of Seattle was eligible to acquire Fort Lawton at little to no cost. The Service League and Kinatechitapi repeatedly petitioned to have a portion of the fort set aside to accommodate a Native cultural center. But the city denied their requests and suggested that they appeal to the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Of course, the city knew that under the policy of Relocation and Termination this would be pointless because the BIA had no authority over urban Indians. To Whitebear and his cohorts, the city’s actions displayed a complete lack of regard for its Native population.18Coming as it did on the heels of the Alcatraz occupation, Whitebear saw the new law as an opportunity for political action.

In March of 1970, Whitebear was the leader of a growing number of younger urban Indians who were tired of the misrepresentation of the American Indian in Seattle politics and frustrated by the city’s unwillingness to negotiate. Inspired by the success of the Black Power movement and by the birth of Red Power and the recent occupation of Alcatraz, and free from the older, more conservative Native leadership, Whitebear organized for an assault on Fort Lawton.” We felt he (Sen. Jackson) had channeled us into oblivion,” said Whitebear. “And that touched off the demonstrations at Fort Lawton.”19 Whitebear and the others felt the time was right to follow the path of those who acted on Alcatraz and attempt to physically occupy Fort Lawton. They sent out a national call for help. As he later wrote, the “‘Moccasin Telegraph’ worked surprisingly well and within days numbers of supporters began arriving in Seattle.”21 Among those pledging assistance were National Indian Youth Council members Clyde Warrior, Vine Deloria, Shirley Whithill, and fellow Colville Randy Lewis. When it became clear that members from the Indians of All Tribes on Alcatraz would be willing to help in the occupation of Fort Lawton, as would similar groups from Canada led by George Abbot, the decision to act was sealed.22

Phase One: Occupation

Whitebear didn’t see the breaching of the Fort’s defenses and gaining access to the area as much of an obstacle as he had spent plenty of time training on the grounds as both a paratrooper and as a special forces soldier, as did a Garry Brey another member of the invading group.23 The most challenging portion to him would be organizing all of the potential occupants that had no training. The night before the invasion, drawing on the connections of his heritage, Whitebear organized a powwow at the Filipino Community hall in south Seattle, both to celebrate the coming operations and to communicate to as many people as possible the plans for the invasion.24 At the powwow Whitebear addressed the potential participants with the message that, “it may get rough. I want you all to hold you temper, in spite of the difficulty and pain you might face. If any of you need alcohol or drugs to get you through this, forget it. I don’t want to make the same mistakes that were made at Alcatraz. I want to win this one.” 25

The efforts of the powwow were successful and on the following morning, March 8, 1970, more than 100 participants mustered into two half-mile long convoys and began the drive to opposite ends of the Fort.26 As the caravans drove towards the north and south ends of the Fort the vehicles made no efforts to maintain operational security as vehicles proudly displayed Native Pride banners from their aerials.27

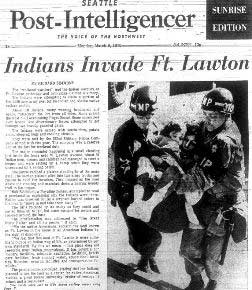

On the morning of March 8, 1970 more than one hundred protesters scaled the fences on both the north and south ends of Fort Lawton, draping blankets over the razor wire as they climbed over. They quickly set up tepees and drum circles and began singing traditional Native songs. A Reserve Military Police (MP) company completing its weekend drilling was surprised by the invasion and, in turn, surprised the invaders. “We didn’t realize there were still soldiers on the base,” Randy Lewis said later. The MPs requested help from Fort Lewis and armed troops soon arrived alongside squads of Seattle police officers. With bolstered numbers they descended on the occupiers and began marching or carrying them away through a blackberry patch toward awaiting trucks. This was done not out of malice said one soldier, but because “the Army always does everything the hard way.”28 While the papers reported little more than this, Randy Lewis recalls a much more violent removal:

“People were injured, MPs were injured, equipment was destroyed, jeeps were flipped over … barracks were torched. We had kids, little kids who came in with us who sought safety under some barracks and the MPs didn’t know who was under there, just that some were under there so they threw these … grenades in there. Tear gas grenades and the kids threw them back out. This continued and finally the kids just torched the barracks. The littlest of kids did the greatest damage; they torched three of the barracks here.”29

Lewis’s version is supported by Lawney Reyes in Reyes’s biography of his brother, Bernie Whitebear. “At times tempers were lost and fighting broke out,” Reyes writes. “The leaders Bernie had selected had to intervene more than once to maintain order. The Indians that were caught were put in the stockade.”30

While the occupiers were removed from inside the fort, the protest continued outside the gates. Indeed, the demonstrators who gathered en masse to continue the fight were a critical component of the invasion’s success. As Reyes recalls, “Outside the main gate of Fort Lawton, five hundred Indians and non-Indian allies assembled to show their support to the invading activists. The Media was there with their cameras.”31 There is considerable debate over the actual numbers of protesters outside the gates. Some estimates claim hundreds of participants while others remember the numbers ranging from fifty to ninety. Those who were outside carried lighthearted signs with messages such as “Custer Wore Arrow Shirts” and “Kill Our Women, Rape Our Buffalo.”32 The protesters remained outside of the front gates for three weeks, thanks in part to the support they received from community members who supplied the vigil, which became known as “Resurrection City,” with food and clothing. Hewlett’s Catering, owners of Tillicum Village, provided a catered meal each day.33 These protesters caused the Army such consternation that two active duty companies were sent to Fort Lawton from Fort Lewis to install nearly one mile of concertina wire around the entrance to prevent any further invasions.34

Despite the army’s new security measures, Indian leaders were anxious to maintain their momentum and the interest of the press, as well as to perhaps exorcise grudges over the rough treatment the protesters had received on March 8. “The beatings we took were not going to be forgotten,” said Lewis about the first invasion.35 Consequently, a second invasion was planned to take place four days later. The group found that the only viable access to the fort was from the least likely of approaches, the water. On March 12, complete with teepees, drums, elderly persons, and children, the group infiltrated the south end of the fort. They scaled the large bluffs abutting the fort by clinging to the root systems of the trees that grew out of the cliffs. They also shrewdly timed the foot patrols of the guards and were able to set up their teepees, build a fire, and begin a drum circle in between the rotation of the sentries. Randy Lewis remembers the reaction of the guard upon discovering the invasion: “The next time he comes by he goes, what the hell! There are a hundred Indians over there drumming and singing. What happened?”36 The MPs soon descended once again, coming in force and in full riot gear. Before they could see the MPs the occupiers heard the thumping of their black jacks as they advanced in unison. Lewis recounts climbing a ridge to get a better look. “I was with Douglas Remington, who was a Ute Indian from Utah of all places … We climbed this ridge and as far as the eye could see there were MPs marching. They crested the hill and we all figured this is it. It’s going to be Wounded Knee all over again.”37 This time the occupiers chose not fight back, but rather fell limp to the ground in nonviolent resistance. “We didn’t want to risk the old people or the Children,” Lewis said. Still, they did not go easily. Lewis remembers Grace Thorpe, the daughter of famed athlete Jim Thorpe saying, “‘I stand over six feet tall and it’s going to take eight of you to move me.’ And it did.”38 Eventually, the occupants were rounded up and once again taken to Fort Lawton’s stockade.

While the city’s general population seemed to be behind the Native group after the occupation, there was considerable dissent from within the Native community. After meeting with Army officials, Whitebear and his group felt compelled to defend their actions to the Native elements of the community who thought they were inappropriate and counterproductive. During a meeting held at the Alaska Native Services building the invaders were faced with strong opposition. Much of it stemmed from the American Indian Women’s Service League and especially its founder, Pearl Warren, who felt that militant action would jeopardize the modest funding the city was already granting to Natives.39Although he himself was a militant activist, Randy Lewis regrets the divisions caused by the invasion. “The old guard in the Service League in many ways felt they were being ignored, resented, and even displaced. If I could do one thing different I would honor those women for what they had done previously, and apologize to them for the ill will that was brought on to them because that was a lot of pain.” Thus, in Lewis’s words, the invasion “both galvanized and factionalized our community.”40

Resurrection City remained outside of the front gates of the fort for over three weeks, complete with functional teepees and continuous demonstrations to block and complicate the mission of the Army personnel attempting to operate in the area. By the end of March, Indian leaders faced a decision. According to Lewis, “We had to decide if we were going to stay or go, so we met again at the Filipino Community Center and decided to call it quits on April 1st. We decided to take down Resurrection City the next day. Frank White Buffaloman, an old Sioux medicine man that lived in the area told the press that there would be a message from the sky that day. Everybody poo pooed him of course and Frank was out there when we were holding our press conference and from up in the sky … Frank had hired a sky writer and it says, ‘Surrender Ft. Lawton.’”41As the teepees were being taken down about fifty Indians, accompanied by television crews and cameras, rushed past the guards for a third and final occupation on April 2, 1970.42 The Natives scattered throughout the base while MPs began making immediate arrests. When Seattle Times reporter Don Hannula reached Bernie Whitebear for comment, Whitebear said that the third occupation was “an effort to reaffirm Indian demands that surplus designated Fort Lawton land be turned over for a multipurpose and education center.”43 As Resurrection City came down and the trespassing Natives spent their last night in Fort Lawton’s stockade, Whitebear announced the transition from occupation to negotiation.44

Phase Two: Negotiation

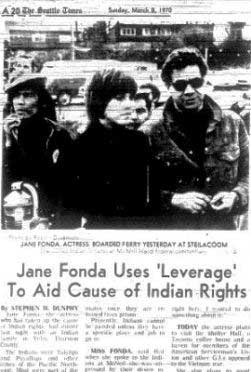

The most immediate success of the occupation of Fort Lawton was the effect it had on public opinion. As Whitebear wrote, “the invasions and occupations had achieved one major objective, gaining commitments of support from the local residents of Seattle.”45 Perhaps even more important than local support was the support of actress/activist Jane Fonda, whose impact on public opinion, not only locally but nationally and even internationally, cannot be understated. Fonda, perhaps more than anyone else, got Bernie Whitebear through the door and brought the politicians to the bargaining table.46 “She broadcast that face and that Barbarella body,” said Lewis of Fonda’s involvement. While she did little at the actual occupation her leverage and media presence granted Whitebear and others the foothold they needed to begin the bargaining process for the land they desired.

Whitebear was advised by attorneys Garry Bass and Blair Paul to form an organization that could be seen as representative of the Natives in Seattle during the negotiations to come. The new organization was named the United Indians of All Tribes Foundation and was sponsored by the National Congress of American Indians, the largest Indian organization in the United States at the time, in addition to more than forty non-Indian organizations throughout King County.47 This level of public support enabled a UIATF committee to gain an audience with BIA commissioner Louis Bruce. The committee, consisting of Whitebear, Randy Lewis, Dr. Frances Svensson and others, successfully convinced Bruce to place a hold on Fort Lawton lands, thereby preserving their status as “surplus” federal land, until further negotiations could be completed. Bruce was later pressured politically by the Department of the Interior to remove the hold because it represented a breach of the BIA’s policy of refusing to deal with urban Indians.48 In the meantime, the hold meant that the city could not acquire the land.

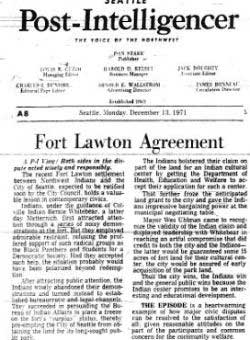

The temporary hold enabled the UIATF to make an application for part of the property prior to the city of Seattle’s application through the Department of the Interior. This early application put the UIATF on equal ground with the city of Seattle in the eyes of the General Services Administration, which was responsible for final disposal of federal surplus property. The early application reportedly enraged Mayor Uhlman, who had been lobbying for the property for years. Whitebear responded by stating that he could “understand how they felt after 10 years of work to get the property for the city, but I remember that we’ve had 300 years of injustice.”49 The move, in conjunction with pressure from Senator Jackson, forced Uhlman to negotiate with the UIATF. Senator Jackson was at the time a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination. As one negotiator pointed out to the Seattle Post Intelligencer, “Jackson turned on the Heat. He needed to improve his image with Indians, and the last thing in the world he wanted was to have a bunch of them here and elsewhere on the warpath.”50

Negotiations started in June of 1971 and were not completed until November when it was agreed that the UIATF would lease twenty acres for a 99-year period with options for successive 99-year leases without renegotiation. The agreement was approved, executed and incorporated on March 29, 1972 and the surplus land was transferred on August 30.51 Bernie Whitebear was sure to refer to the agreement as anything but a treaty: “it’s not a treaty. The white man doesn’t keep treaties. It’s a legal, binding, agreement.”52

With the agreement reached, the next task was to develop the program for the cultural center, to design the buildings, and to seek funds for their construction. In March of 1973 the city of Seattle designated $500,000 of its general revenue sharing funds for the development of the cultural center. An additional grant of $250,000 was awarded from the Economic Development Administration (EDA). Both the city and the EDA later contributed more funds to the project in addition to the timber the UIATF received form the Colville, Quinault, and Makah Tribes. In the end, the total construction cost reached $1.2 million.53 With the funding for the center secured, the groundbreaking occurred on September 27, 1975. Eighteen months later, on May 13, 1977, the building, which Lawney Reyes helped design, was dedicated.

The invasion of Fort Lawton was not a total victory. The activists had hoped to secure all ten thousand acres of surplus land and in the end received only forty.54 And the militant nature of the protest caused dissension within Seattle’s Indian community along generational lines. Yet in other important respects the invasion was a momentous success. Alongside the Alcatraz takeover, it signaled to the city of Seattle and the nation that urban Indians would fight for rights, redress, and respect by any means necessary. In this way, it is inseparable from other radical movements for social justice and civil rights involving persons of color, women, and the working-class that have defined the period between the late 1960s and mid 1970s. The invasion also resulted in the formation of the United Indians of All Tribes Foundation, a crucial institutional body that continues to unify the Native community across diverse tribal affiliations. Equally important, the Daybreak Star Center filled, and continues to fill, a vital place in Seattle’s Native community as both a provider of essential social services and a preserver of Native history and culture. The UIATF named the center Daybreak Star after a vision by Black Elk, a Sioux medicine man. According to the center’s official history, Black Elk’s vision foretold of “a ‘daybreak star herb,’ the herb of ‘understanding,’ falling to the ground and blossoming forth on one stem in four directions … a black, a white, a scarlet and a yellow. The four colors symbolize the four races of mankind united in four directions … spiritually, physically, mentally and emotionally. On March 8, 1970, the herb fell to the ground.”55

Copyright © Lossom Allen 2006

HSTAA 498 Fall 2005; HSTAA 499 Spring 2006

1 Lawney L. Reyes, Bernie Whitebear: An Urban Indian’s Quest for Justice(Tuscan Arizona: The University of Arizona Press, 2006), 100

2 Bernie Whitebear, “Self-Determination Taking Back Fort Lawton: Meeting the Needs of Seattle’s Native American Community Through Conversation” (Seattle, United Indians of All Tribes Foundation, 1994)

3 Whitebear, “Self-Determination Taking Back Fort Lawton,”3

4 Randy Lewis, interviewed by Teresa Brownwolf Powers, Daybreak Star, November 12, 2005

5 Coll-Peter Thrush, “The Crossing Over Place: Urban and Indian Histories in Seattle,” (PhD diss., University of Washington, 2002), 303 and 315

6 Thrush, “The Crossing Over Place,” 307

7 Whitebear, “Self-Determination,” 3

8 Blair Paul, interviewed by Lossom Allen and Trevor Griffey, April 26, 2006

9 Thrush, “The Crossing Over Place,” 314. The Central District is home to Seattle’s largest concentration of African Americans.

10 Blair Paul interview

11 Blair Paul interview

12 Kathleen Dahl, “The Battle Over Termination on the Colville Indian Reservation,” 32

13 Ibid, 81

14 Whitebear, “Self-Determination,” 5

15 Randy Lewis, 2nd interview

16 Collin Calloway, First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian History, 450

17 “Discovery Park 1972 Original Master Plan: Commemorative Edition Reissue 1992,” (Seattle: Friends of Discovery Park), 15

18 “The Indian Struggles,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 27, 1974, sec. A, p. 6

19 Shelby Scates, “Whitebear Leads the Indians to Victory in Ft. Lawton Battle,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, December 5, 1971, p.5

20 Reyes, Bernie Whitebear, 98

21 Whitebear, “Self-Determination,” 5

22 Randy Lewis, 1st interview

23 Randy Lewis, 1st interview.

24 Whitebear, “Self-Determination,” 5

25 Reyes, Bernie Whitebear, 100

26 Richard Simmons, “Indians Invade Ft. Lawton,” Seattle Times, March 10 1970

27 Whitebear, “Self-Determination,” 5

28 “Army Disrupts Indian Claim on Ft. Lawton,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer,

29 Randy Lewis, 1st interview

30 Reyes, Bernie Whitebear, 100

31 Reyes, Bernie Whitebear, 100

32 Don Hannula, “Indian Picket Line Remains at Ft. Lawton,” Seattle Times, March 11, 1970, sec. A, p. 1

33 Randy Lewis, 2nd interview

34 “Reinforcements for Ft. Lawton,” Seattle Times, sec. A

35 Randy Lewis, 2nd interview

36 Randy Lewis, 2nd interview

37 Randy Lewis, 2nd interview

38 Randy Lewis, 2nd interview

39 Reyes, Bernie Whitebear, 103

40 Randy Lewis, 2nd interview

41 Randy Lewis, 2nd interview

42 Don Hannula, “Indians Again Try to Occupy Fort Lawton; 80 Detained,”Seattle Times, April 2, 1970, sec. A, p. 1

43 Ibid

44 Whitebear, “Self-Determination,” 6

45 Whitebear, “Self-Determination,” 6

46 Stephen Dunphy, “Jane Fonda Uses ‘Leverage to Aid Cause of Indian Rights,” Seattle Times, March 8, 1970, sec, A, p. 20

47 “The Indian Struggles,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 27, 1974, sec. A, p.6

48 Ibid, 6

49 Shelby Scates, “Whitebear Leads the Indians to Victory in Ft. Lawton Battle,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, December 5, 1971, p.6

50 Ibid, 6

51 Summary History of Relationship Between the City of Seattle and the United Indians of All Tribes Foundations, (Seattle: United Indians of All Tribes Foundation), 1

52 Shelby Scates, “Whitebear Leads the Indians to Victory in Ft. Lawton Battle,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, December 5, 1971, p.5

53 “All of the people who are a part of the United Indians of All Tribes Foundation’s history, and all of their ancestors who endured and survived in order that the herb of understanding might blossom,” United Indians of All Tribes Foundation: A Ten Year History: March 8, 1970- March 8, 1980 (Seattle: United Indians of All Tribes, 1980), 4

54 Randy Lewis, 2nd interview

55 United Indians of All Tribes Foundation, “All of the people,” 2