Mount Baker Park, overlooking Lake Washington, was developed by J. C. Hunter of the Hunter Tract Improvement Company in 1907. Hunter and associates bought the land and decided to subdivide it based on the recommendation of the Olmstead Brothers who proposed that a public park named “Mount Baker Park" be established near Lake Washington to complete their plan for Seattle’s parks and boulevards. Hunter used the label Mount Baker Park Addition for his planned neighborhood of single-family homes, which is now known simply as Mount Baker. After purchasing the land, he hired the Cotterill and Whitworth engineering firm to design the initial layout of the subdivision. The plat covered a 70-block area, spanning over 200 acres, and was completed by July 1907. In 1908, the company donated land to the city for the public park.

In her neighborhood historic context study, Carolyn Tobin reports that the "new subdivision was one of the largest planned neighborhoods in Seattle at the time of its platting," and the first subdivision to be included in the city's Olmstead-designed plan for parks and boulevards. Soon after sales began, the Hunter Company encouraged homeowners to launch the Mount Baker Park Improvement Club in 1909. Now known as the Mount Baker Community Club, it has represented Mount Baker residents ever since.

From the beginning, the Hunter Tract Improvement Company intended an “exclusive upper-income community” and a “high-class residential section of the city.” Most of the lots and homes in Mount Baker Park were sold between 1907 and 1922 and in newspapers they were advertised as being in a “highly restricted district.” This language was often used to signal to potential homeowners that the neighborhood was for Whites only. The Hunter Company was so adamant about enforcing these racial restrictions, that they twice filed lawsuits to prevent Black families from moving into the neighborhood. Because the development company's original declaration of restrictions had not included a racial restriction, the court refused to intervene. The company appealed to the Washington State Supreme Court in 1910 seeking to annul contracts of sale for properties in Mount Baker Park that had been bought by Black families.

The first case to reach the State Supreme Court was Hunter Tract Improvement Co. v. Stone (1910). Marguerite Foy (a White woman) had bought a lot in block 18 of Mount Baker Park Addition for a Black woman and her husband, Susie and S. H. Stone. When the company found out that the Stone family was going to be moving into the residence, and not Marguerite Foy, they went to court to try to cancel the contract of sale. They maintained that the contract was intended for Ms. Foy, and they would not have sold the house to the Stone family because they were of the “Negro” race and Susie Stone wrongfully concealed her race from them. The company further argued in court that Mount Baker Park would become less valuable and popular if Black people were to start living there and that they already sold and advertised the neighborhood as Whites-only to other homebuyers. But the State Supreme court ruled in favor of Susie Stone, deciding that she and her husband’s contract was valid and that they could continue to reside in their home in Mount Baker.

Despite losing the Stone case, Hunter Company brought another case to the Washington State Supreme Court on similar grounds on December 29th, 1910: Cole v. Hunter Tract Improvement Co.(1910). In 1907, the company had issued a contract of sale to David Cole, via his attorney. Hunter did not find out that David Cole was Black until almost a year after the execution date of the contract, and after all payments for the land had already been made. The company used the same argument as in the previous case, claiming that they needed to maintain the value and prosperity of their subdivision by keeping it Whites-only, but again the court rejected the reasoning, ruling in favor of David Cole, allowing him to keep owning his property in the neighbohood. The company may have lost both judgements, but their persistence in filing lawsuits demonstrated that the developers were determined to maintain an all-White neighborhood and would spare no expense to do so.

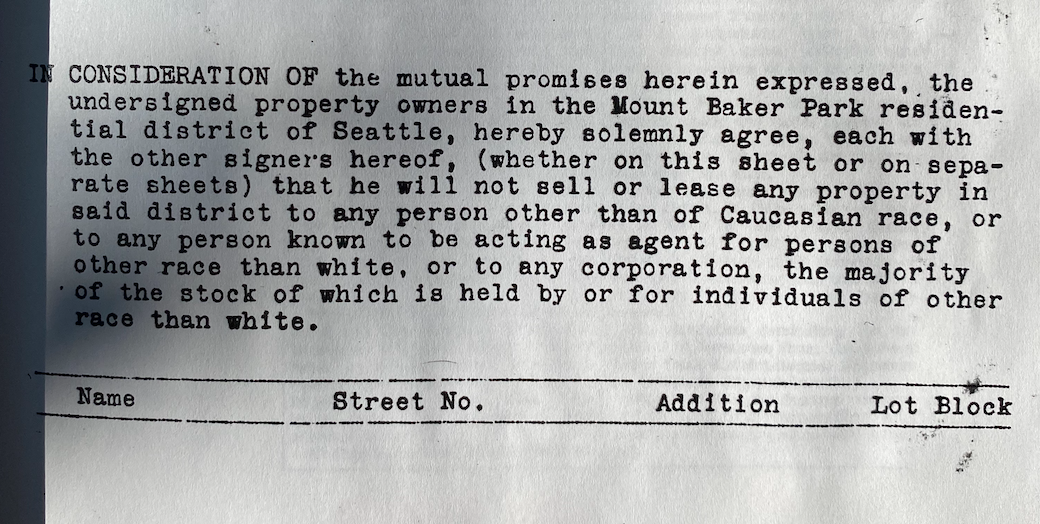

Despite two documented instances of failing to legally enforce racial segregation in Mount Baker Park, the neighborhood continued to restrict on the basis of race for decades. In this the company found a determined ally in the Mount Baker Improvement Club. The Improvement club acted as a neighborhood association for Mount Baker residents, and in 1915 they formed a restrictions committee. In 1926, the President of the Mount Baker Improvement Club, Henry F. Dailey stated,

"The most valuable element of the club's work has been in compelling adherence to the building restrictions imposed upon the property in this subdivision. The observation of these restrictions has given the subdivision much of its attractiveness."

As mentioned earlier, the subdivision's list of original restrictions had not included an explicit mention of race. But there were detailed rules about the kinds of buildings that were allowed and their uses, all intended to maintain a wealthy neighborhood of single-family homes. The restriction committee zealously enforced rules against business activities and multifamily structures. Another document that the Mount Baker Improvement Club produced stated, “Adequate building restrictions ensure a desirable class of homes, and business houses and apartments are prohibited.” Even though race was not explicitly mentioned, it was an important part of committee's effort to keep their neighborhood “desirable.”

Mount Baker discriminated against all non-White people, and the Mount Baker Improvement Club had a long history of anti-Japanese actions. In 1919, in addition to the Club’s restriction committee, they also formed a Japanese Investigation Committee. That committee came to the conclusion that “the Japanese already had the best bottom farmlands and should be kept out of Mount Baker District. The club's 1919 scrapbook records that there was a fear of ‘Japanese invasion of the district” (Tobin, 28).

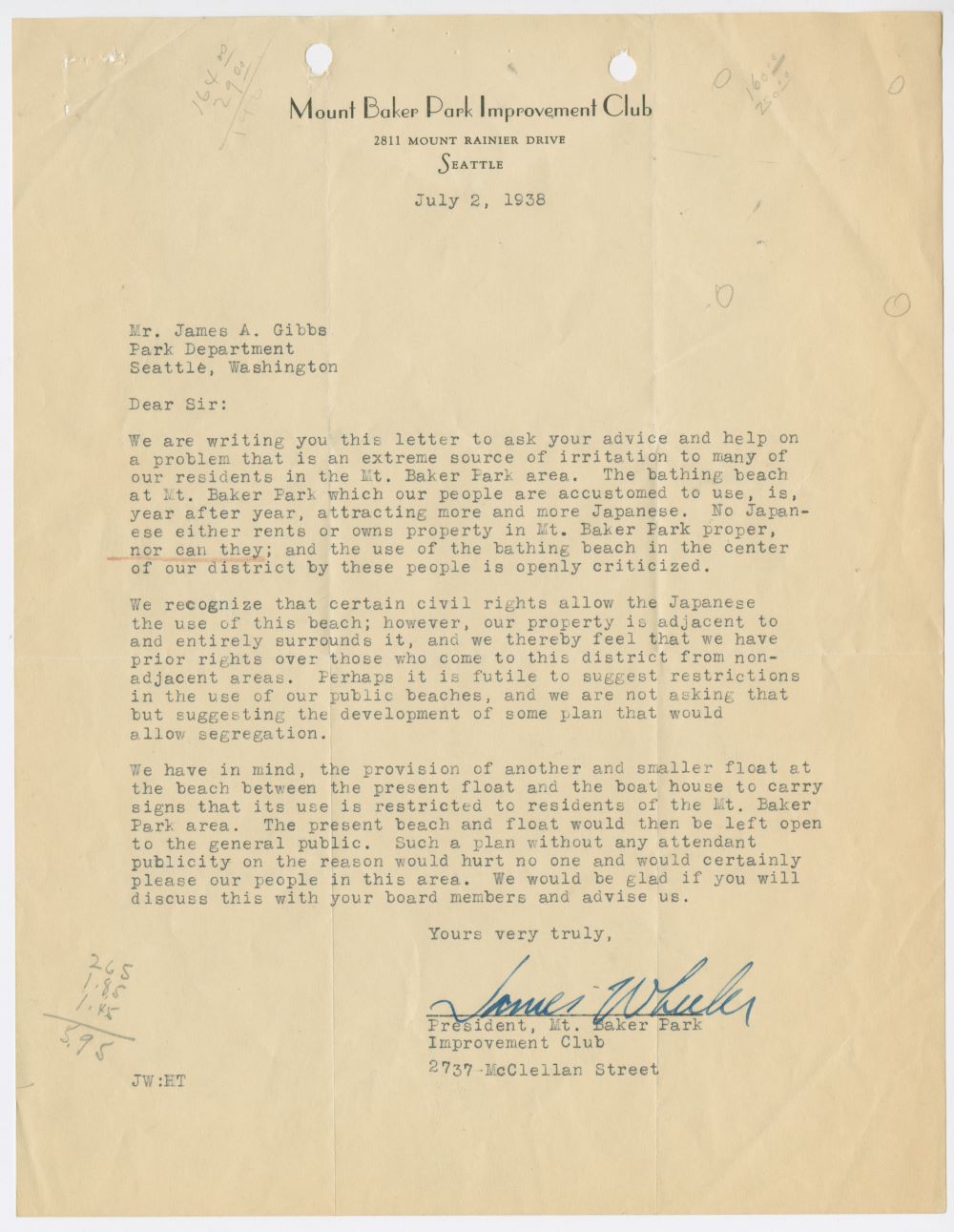

The anti-Japanese actions did not stop there. In 1938, the president of the Mount Baker Improvement Club, James Wheeler, sent a letter to the Seattle Parks Department, requesting that the public beach near Mount Baker Park be restricted to Mount Baker residents only. He wanted to keep Mount Baker segregated and limit the number of Japanese Americans in proximity to his community. Mr. Wheeler states, “The bathing Beach at Mt. Baker Park which our people are accustomed to use, is, year after year, attracting more and more Japanese. No Japanese either rents or owns property in Mt. Baker Park proper, nor can they.”

This is significant for a couple of reasons. Firstly, it shows the extreme arrogance of the community association which not only enforced racial exclusion in their neighborhood but felt that it was their right to ban Japanese Americans (and presumably other people of color) from a public beach. Secondly, the statement that "No Japanese either rents or owns property in Mt. Baker Park proper, nor can they” suggests very powerful methods of exclusion. It implies the existence of legal tools of exclusion (racial restrictive covenants).

We know that the neighborhood association mounted a petition campaign, probably in the late 1920s at the same time as Capitol Hill, Queen Anne, and other campaigns that imposed racial restrictions retroactively when hundreds of White residents filed notarized petitions binding their properties. We don't yet know whether petitions were actually filed for Mount Baker Park. Our research has so far identified deeds for four properties filed in the 1920s imposing racist restrictions on future occupants on those homes. We expect to find more as our research continues.

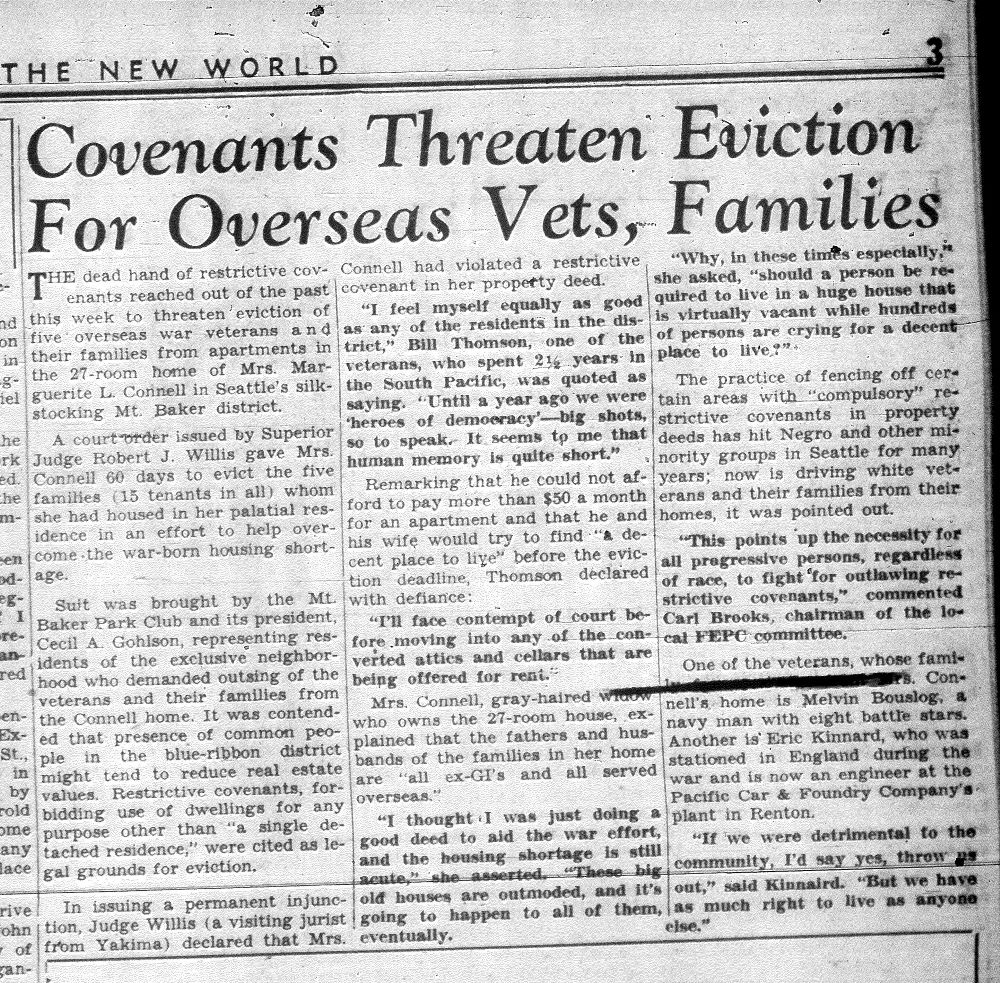

The barrier against non-White people moving into Mount Baker continued for decades. In 1950 there is a record of concern regarding a “colored” family moving into the neighborhood, but residents backed off when they discovered that the family was Brazilian and supposedly not Black. Discrimination towards Asian Americans also continued. Following World War II and the internment of Japanese Americans, strong anti-Japanese rhetoric and discrimination continued in Mount Baker into the 1950s (Tobin, 40).

Due to its exclusionary origins and the many efforts of White residents to ensure no people of color could live there, Mount Baker remained White and upper-income until the 1960s. A period of White flight took place in the early 1960s, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 made housing discrimination on the basis of race illegal. In 1967 the Mount Baker Improvement Club formed a committee to revitalize Mount Baker, and part of that process included trying to undo the earlier racial discrimination that the Improvement Club played such a large role in. By the 1990s, however, housing prices in Seattle began to soar, and although the area is more racially and ethnically diverse than it once was, it is still an upper-income, exclusive community.

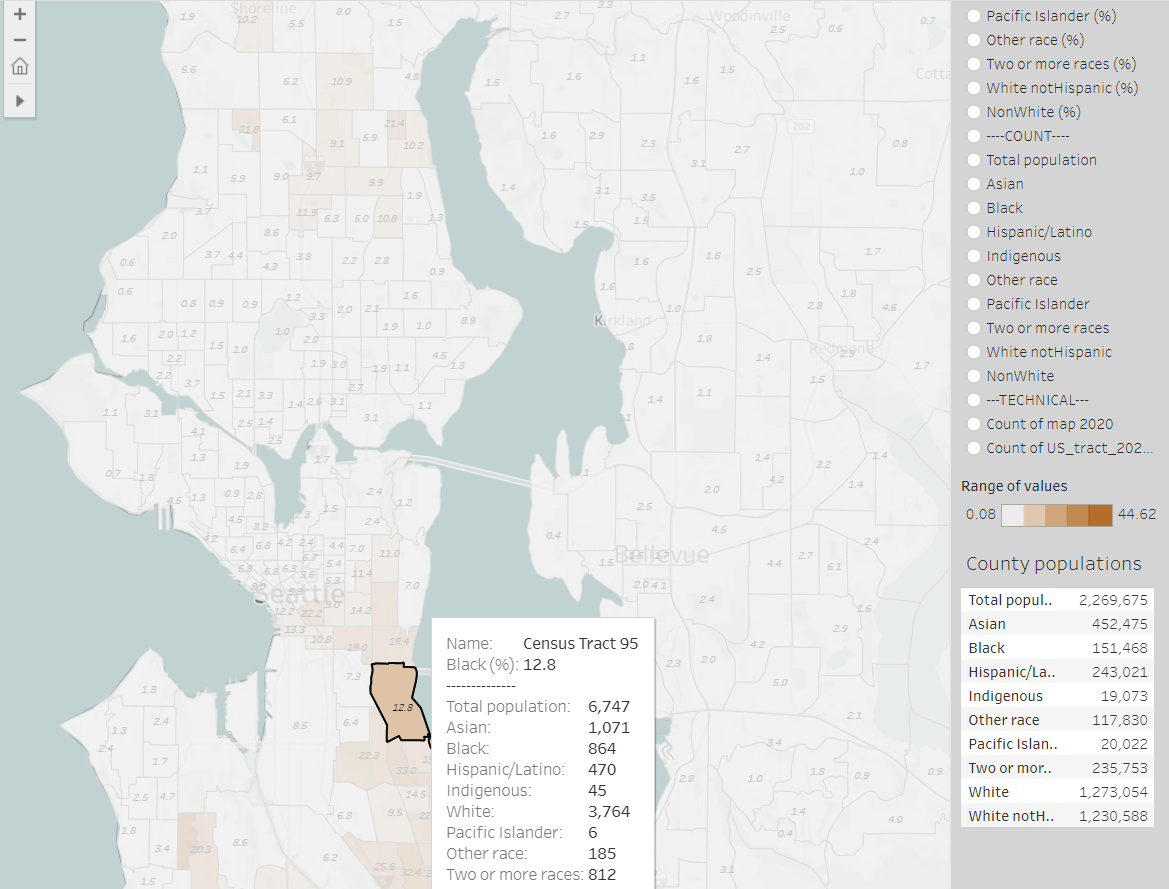

According to 2020 census data, the Mount Baker District had a median household income of $128,996 and 67.7% of residents had an education level of bachelor's degree or higher. Residents were 56% White, 16% Asian, 13% Black, and about 15% multiracial or "other race." Today (2023), the Mount Baker Community Club’s website goes to great lengths to talk about the ways in which they have included people of different racial groups into their community but fails to mention the neighborhood's deep history of racial exclusion. It is clear that current Mount Baker residents take pride in the ways in which their community has made improvements in diversifying racially and ethnically. Despite this, Mount Baker will continue to fail its community members of color until it has the courage to reckon with its deep history of racial exclusion and discrimination.

Explore our map of racial change

Below is a screenshot of our interactive map showing the 2020 population of the census tract encompassing Mount Baker. Click to visit the interactive version which shows population changes for each decade from 1950-2020. Use the filters to show number counts and percentages for various racial groups.

Sources:

Carolyn Tobin, "Mount Baker Park Historic Context Study,"City of Seattle Department of Neighborhoods, 2004

Judith Yarrow, "Mount Baker Park Improvement Club Clubhouse," Mount Baker Community Club, 2018

Kathleen Kemezis, "Samuel and Susie Stone win legal battle for right to live in Seattle's exclusive Mount Baker District on June 7, 1910," HistoryLink.org

"Hunter Tract Improvement Co. v. Stone, 58 Wash. 661 (1910)" Case Law Access Project, Harvard Law School

"Mt. Baker Park Club, Inc. v. Colcock", Justia US Law

Articles of Incorporation for Blue Ridge Club, Inc. (courtesy Doug Dunham)