By the early 1970s, Chicano/a civil rights activism through war on poverty efforts and the genesis of the Chicana/o youth movement in Washington set the conditions for the modern incarnations of the farm worker movement in the Yakima valley region. Through their activist and educational efforts, many Chicanos/as now had the political organizing skills to combat farm worker exploitation. UFW or UFWOC organizers used these skills in their organizing efforts in the Yakima Valley hop strikes of 1971.

As strike organizer Guadalupe Gamboa recalled, “the first organizing efforts actually took place in the valley, [led by] a couple [of] students, Roberto Trevino and his brother, Carlos Trevino….The Trevinos had gone down [to the Yakima Valley]. They were all students at that time at the University of Washington and had been involved in the grape boycott and had heard all about Cesar Chavez. So when they went down, they were drinking and talking to some of their buddies, who were complaining that they were being paid very bad at this hop farm – it was in the fall – and that they were all planning to quit, so they said, ‘Well, instead of quitting, why don’t you organize strike like they did in California? Ask for better wages.’ In fact, that’s what they did.”1 They formed the first strike organizing committee and led wildcat strikes in the hop fields of Yakima Valley in 1970.

When asked “why hops?” by one newspaper, Gamboa responded by maintaining that the working conditions are the worst for farm workers in the hop fields. According to Trevino, farmers offered employees “bad facilities”and seven-day work weeks without overtime pay.2

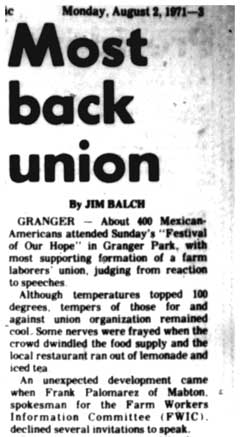

Many Chicana/o activists assisted in the strikes, including Loupe Gamboa, who left an internship at the state Attorney General’s Office to become the strike’s legal advisor.3 The first strike originated in Granger, Washington, and soon reached the small town of Matson. The UFW also organized workers to strike at the Big Chief and Little Chief Hop ranches in the lower Yakima Valley.4 As Gamboa notes, “eventually the hop strike spread to about fourteen or fifteen different ranches. We caught the growers by surprise and they were in the middle of harvest, which has to be done right on time; otherwise the hops lose their value.”5

Strike activity in the hop fields was run through the United Farm Workers Co-op and Service Center, because of the center’s support for the grape boycott. On weekends there were hundreds of advocates surrounding the Safeway stores throughout the Yakima Valley to prevent the sale of grapes. Growers reacted by attempting to enact House Bill 550, a measure that would give them protection against harvest-time strikes.6They also reacted with violence and firearms. In one case, Gamboa and Trevino brought court action against the growers alleged to have brandished firearms and assaulted employees who were seeking to organize a union.7

In the end, the growers succeeded in miring the UFW hop boycotters in surface bargaining. The following season, growers blackballed laborers, refusing to hire those who were prominently engaged in union activity. Despite this setback, the group was successful in achieving higher wages for workers, but not in forming a union.

After these strikes, UFW efforts continued under the direction of Gamboa and the Trevinos, but after a while the efforts died down. According to Gamboa, “that had to do with two things: one is that there were a lot of Mexican foremen that did not like the union and they gave the growers good advice on how to stop the union movement. They convinced growers that the best way to get rid of the union (1) was to raise the wages in general and (2) to treat the workers right, and they said that workers loved to have caritas (barbecues outside) and beer, so it got customary for a little while that they would drink beer and eat caritas on payday.” Many people previously engaged in the fight for a farm worker’s union forgot the reason for their struggle. As Gamboa states, people started to think “We don’t need a union. Why should we join a union while the farmers are becoming our friends? They’re treating us right. They’re even providing us free beer and free carnitas.”8

Impediments to organizing also led to the dissolution of farm worker’s efforts to unionize. According to Yolanda Alaniz and Megan Cornish, “Some ranches required no picketing and others gave in after a few days. But many owners attacked strikers with guns, dogs and fists; the owners preferred to risk their crops and their ranches rather than give in.”9 In addition to violence, more conservative Chicanas/os were chosen by farmers to form a company union called the Agricultural Working People’s Committee (AWPC) as an “alternative” to UFW. There were as many as 22 members of AWPC. Most were either labor contractors, foremen, or other supervisory personnel. Often times, AWPC sent these “farm workers” to testify for anti-labor legislation at the state capitol.10Supported by local news media, AWPC smeared the UFW, accusing it of charging enormous dues. One newspaper article maintained that the UFW did not represent the majority of farm workers.11

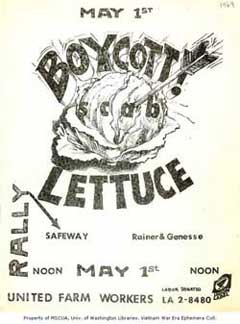

Despite the odds, the UFW union continued its work, becoming more visible from 1970 through 1972. Perhaps what attributed to the movement’s decline were the demands of the UFWOC, with organizers being called to California in the summer of 1972 to fight the anti-labor legislation known as Proposition 22. The shift in focus to organizing work in California and the overall lack of resources slowed activity in the Yakima Valley by 1972. Gamboa was gone for most of the decade as were other organizers, leaving few to sustain local campaigns. “So in my absence, Roberto Trevino stayed here and continued organizing…but, as I understand it, most of the efforts were directed at keeping the boycott going in Washington. It was the lettuce boycott, and then it turned into a grape and lettuce boycott, where they had to go and organize people to go and picket in front of the Safeways and in front of Luckys and the stores that sold the lettuce and the grapes.”12

Trevino’s organizing work helped to maintain a constant UFW presence in the valley. El Movimiento, though temporarily dormant in the fields, continued elsewhere in Washington, as Chicanos solidified their institutions to protect the gains made in the 1960s and 1970s. The birth of Radio KDNA was perhaps the most notable of the institutions created. The station would prove instrumental in reviving the UFW union in the 1980s.

Next: Ch. 8, Radio KDNA: The Voice of the Farm Worker, 1975-1985

“A History of Farm Labor Organizing, 1890-2009” includes the following chapters:

- Toward a History of Farm Workers in Washington State

- The IWW in the Fields,1905-1925

- The 1933 Battle at Congdon Orchards

- Asians and Latinos Enter the Fields

- Mexican-American Struggles to Organize, Post-WWII[](kkk_yakima.htm)

- El Movimiento and Farm Labor Organizing in the 1960s

- UFW’s Yakima Hop Strikes, 1971

- Radio KDNA: The Voice of the Farm Worker

- Resurgence of the UFW of WA State in the 1980s

- The Struggle Continues, 1997-2006

- Bibliography

Copyright (©) Oscar Rosales Castañeda

1 Guadalupe Gamboa Interview, 9 April 2003 by Anne O’Neill.

2 Bill Harris, “Hops Heads List of Chavez’ Union,” Tri-City Herald, 25 April 1971.

3 Yolanda Alaniz and Megan Cornish, Viva La Raza, A History of Chicano Identity & Resistance (Seattle: Red Letter Press, 2008), 298.

4 For more on the growers’ perspective of the strikes in Mabton and at the Yakima Chief ranches, see Bill Harris, “Hop Ranch Wants Chavez Pact,” Tri-City Herald, 28 April 1971. For news on the continued strikes on the Yakima Chief ranches, see “Chavez Halts Talks, Hop Strike Expected,” Tri-City Herald, 27 June 1971.

5 Guadalupe Gamboa Interview.

6 Kirk Smith, “Farm Strike Bill Debated,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 26 February 1971. Trevino, Gamboa, and other farm workers fought against the bill in court. By 1972, this proposed farm labor bill did not pass through legislation. Shelby Scates, “Farm Workers Organizing, Bill Meets Virtual Death,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 1 February 1972.

7 Dixie Koenig, “Hops Labor Trial Underway,” 13 January 1971.

8 Ibid

9 Alaniz and Cornish, 299.

10 In one newspaper article, the UFWOC quizzed the leaders of the AWPC. Ted Escobar, “UFWOC Men Quiz Leaders of AWPC,” Tri-City Herald, 27 February 1972.

11 Bill Harris, “Hop Workers Deny Chavez Tie,” Tri-City Herald, 18 July 1971.

12 Guadalupe Gamboa Interview.