From humble beginnings on the Colville reservation in the 1930s to the Fort Lawton protests in 1970, Bernie Whitebear dedicated his life to Indian activism and the advancement of urban Indian communities and urban Indian politics. “No one helped more Indians in need in the last century than Bernie Whitebear,” said Vine Deloria Jr., the distinguished Lakota author and educator.1 In the 1950s, Whitebear supported Indian fishers in the Nisqually area. In the 1970s, he helped engineer a victory at Fort Lawton and opened the Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center on land that Indians had sought to reclaim from the United States government. Continuing the fight for urban Indian justice, Whitebear remained the most influential Native leader in the region until his death in 2000. In 2011, the city that is named for one Indian leader renamed one of its streets to honor another.

In His Elders’ Footsteps

Old Cashmere St. Paul was one of the elders of the tribe and a rich source of information about the traditions of the Sin-Aikst people and their history.2 Lawney Reyes describes Old Cashmere’s reaction to the sight of young Bernie as prophetic; he saw in Whitebear the hope of his ancestors, including Whitebear’s uncle and namesake, Chief Bernard, and his grandfather, White Grizzly Bear. “I hope you grow strong and are smart enough to deal with the white man… Don’t forget they are the trespassers on our land. They do not own it.”3

Bernie Whitebear (born Bernard Reyes) came into the world on September 27, 1937 at the Colville Indian Agency Hospital in the town of Nespelem on the Colville Reservation.4 The third child born to Julian and Mary Reyes, Whitebear was born during a time of great change for the tribes who lived on the Colville Reservation. His mother was a Sin-Aikst whose tribe made the Colville reservation home. His father was an immigrant from the Philippines who had arrived in America in 1912.5 With his parents always searching for steady work, sometimes harvesting apples on an orchard or working for a lumber mill, Whitebear spent his early years traveling around upper eastern Washington, on and off the reservation. Lawney Reyes, Whitebear’s older brother, described their upbringing on the reservation as being extremely impoverished.6 “If you could survive the reservation, you could survive anything.”7 Recalling his childhood, Reyes noted that growing up on a reservation was in some ways akin to a concentration camp; the small size and poverty of the reservation prevented the Native tribes from living in their accustomed ways and while at the same time depriving them of the knowledge they needed to be successful in the surrounding society. Although they grew up in a home without running water or electricity, and hunted for their supper, the Reyes siblings thought little of it because they thought everyone lived like that.8

The poverty of the reservation was exacerbated by the completion of the Grand Coulee Dam and the resulting cultural and physical destruction that followed. For non-Native Americans, the dam stood as a symbol of progress; the electric turbines would power shipbuilding and plane construction industries west of the Cascades and the reservoir created by the 550ft high concrete embankment would give irrigation to hundreds of thousands of acres of farmland. For the local tribes including the Sin-Aikst of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, however, the dam stood as a symbol of destruction and another reminder that the American government did not respect or care about Indian peoples. With the completion of the dam came the flooding of Kettle Falls, the flooding of their usual and accustomed grounds for berry picking and hunting, and even the flooding of their towns and ancestral grave sites.

The Grand Coulee Dam changed everything. Before the completion of the dam and the large reservoir that filled up behind it, now known as Franklin Delano Roosevelt Lake, the Sin-Aikst spent a significant part of their lives harvesting and processing salmon at traditional sites such as Kettle Falls. Because the dam did not include a fish ladder and thus prevented salmon from making it upstream, the Sin-Aikst and other members of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation lost one of their central cultural and economic tenets; their cultural identity came into crisis and their already fragile economy became even more rigid and destined for poverty. In addition, the tribe was forced to relocate Bernie Whitebear’s hometown, Inchelium. Houses, communities, and even their ancestors’ graves had to be relocated to higher, less productive land.9 Old Cashmere’s blessing was not given to Whitebear in order to fight against inequalities of the past, but to fight against the inequalities that he witnessed in his own lifetime. Whitebear learned the cultural, communal, and economic importance of land from an early age.

Bernie Reyes also learned the importance of personal relationships. In the absence of his mom, who divorced his father when Bernie was two years old, his older sister Luana stepped in and acted as a motherly figure, helping with his daily needs and preparing him for school, while Lawney taught Whitebear how to read the forest and fish for trout.10 During the time his siblings were off at school, his father regularly took time from his busy schedule of looking for work as a day laborer or migrant worker to raise Whitebear to be self-sufficient on the land and to uphold the values of fairness and justice. Despite his mother’s absence, his father continued to raise him on the reservation, as he was well liked in the community and accepted as one of their own. “Because we were accustomed to hard times, we were able to survive. We had learned many times before what it was like to go without,” Lawney recalls of the extreme condition of poverty in which they grew up.11 The cold winters were the hardest and the longest; the creeks froze over preventing them from fishing for trout and winter was also the hardest part of the year for their father to find work. Lawney remembers that during the winter of 1942, when Whitebear was 5 years old, they had to ration their food once the creeks froze over until a friend of their father was able to shoot a deer and give them a hindquarter.12That following spring, their father taught Lawney and Bernie how to plant and irrigate a garden, a task that Whitebear took up with much enthusiasm and curiosity, excited at the ability of tiny seeds to become large amounts of fresh food. Lawney describes that through the garden Whitebear began to “appreciate the results of hard work.”13 After eating at a restaurant and being curious when his father paid with money for the first time, his father explained, “You have to pay someone if he gives you something. Nothing is free.”14 Lawney recalls that this sentiment of valuing what people own, especially land, resonated with Whitebear and helped shape his future activism for Indian land rights.

Fishing wars

After completing high school, Bernie Reyes moved to Seattle where he enrolled in in the University of Washington in the fall of 1955.15Not knowing what to study and feeling a strong need to find work to support himself, he withdrew from college the following spring and moved to Tacoma to live with his mother, who had married Harry Wong and had several more children. Bernie looked for work. Laura Wong-Whitebear, Whitebear’s younger half sibling, recalls how Whitebear, despite how busy he may have been, always took time to care for his family. With a soft laugh she said that based on how many times she got Whitebear to drive her around to school events and places around town she felt like she was “abusing” him.16She recalls how he never failed to help out at home however he could and that he always did it with a smile and sense of humor. While the rent was free, his job search proved unsuccessful until one day in the summer of 1956 he ran into Bob Satiacum, a Puyallup Indian, who offered to give him job fishing on the Puyallup River.

Bob Satiacum, like many other Puyallup and Nisqually Indians, relied on salmon fishing in the Nisqually river basin using canoes and drift nets as a form of subsistence, just like his ancestors had done for countless generations before him. Salmon fishing was such a vital component of Pacific Northwest Indian food and culture that during the signing of Indian Treaties in the 1850s by Washington tribes and Governor Stevens, tribes were adamant in including the “right of taking fish at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations”17. By the mid-20th century, however, those rights had been lost as the state established conservation policies, licensing, and regulations governing fishing. Deforestation, urban development, and dam construction for irrigation and hydroelectric power, combined with unsustainable commercial salmon harvest placed a large strain on the various species of salmon’s ability to reproduce and thrive. While the number of salmon caught by Indian fishers was far lower than the number caught by commercial fisheries, game wardens routinely harrassed and arrested Indians for violating fishing regulations.18

During the late 1950s, some Indians began to take an activist approach towards protecting their fishing rights, conducting “fish-ins.” When Bernie started his summer job of catching salmon with Bob Satiacum, he found himself in the middle of this campaign. Lawney recalls that Bernie wore feathers and traditional clothing during various fish-in protests, and often tried to infuse his humor and imagination into the potentially dangerous events.19 Victories and setbacks for the Indian fishers ebbed and flowed in the courtroom during the ‘50s and ‘60s with conflicting judicial policies in cases such as 1957’s Washington v. Satiacum and 1963’s Washington v. McCoy20 which favored and disapproved of, respectively, the rights of the Indian fishers to catch their fish in manners guaranteed by their treaty rights. Until celebrities such as Marlon Brando lent their fame to support activists in 196421, much of the press portrayed the Indian fishers in a negative light, such as the Seattle Times January 8th 1963 article with the headline “Skagits on the Warpath?”22 Not until the 1974 _U.S. v. Washington,_commonly known as the “Boldt Decision,” in which Indians were given access to 50% of the harvestable catch of salmon and made co-managers in the state’s hatcheries, did Indians see real victory and vindication of their treaty rights.23

After a year of fishing and protesting with Bob Satiacum, in the fall of 1957 Whitebear decided to join the army.24 He received his basic training at Fort Ord, California and then was transferred to Fort Campbell in Kentucky to become a radio operator25 and paratrooper, eventually earning the qualifications to become a green beret.26 When his tour of service ended in 1959, he received an honorable discharge and found work at Boeing assembling parts for aircraft. He enlisted in the Army Reserve Special Forces and continued to train in the Wasatch Mountains in Utah in the summers.

While working full-time at Boeing, Whitebear still made time to visit with his family and the urban Indian community in Tacoma. He maintained his friendship with Bob Satiacum and continued to support the Puyallup and Nisqually Indians fighting for treaty and fishing rights. Satiacum and Billy Frank Jr., Nisqually, took the lead in advocating for their treaty-protected rights to fish through increased protests and events to catch the public eye and gain popular opinion. Not taking a lead role in the protests, Whitebear however did notice the power the Indian community had when it worked together to fight for civil rights issues. This inter-tribal Indian community that formed during the 1950s in Tacoma and many other cities throughout the United States was a relatively new phenomenon and a by-product of mid-century federal termination policy.

Reservation termination and Indian relocation projects were the central policies adopted by the federal government under Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) Commissioner, Dylan S. Meyer, after 1950. Tribes across the country were targeted for termination, where jurisdiction of tribal lands would fall under the state and county where they were located, effectively eliminating tribal sovereignty. At the same time, government programs encouraged tribal members to relocate to cities where it was thought they would be forced to assimilate to Western culture.27 BIA propaganda of the time showed Native Americans proudly working in factories and enjoying all the luxuries of the modern 50s life. In return for giving up reservation life, the BIA offered free job training,medical care, and housing for one year.28

The promise of the propaganda posters rarely held up in real life, however. Many found the job training programs inadequate and steady employment hard to find. The resulting poverty led many Indians to congregate in districts of low-income housing.29 Job insecurity, poverty, and a lack of the cultural support system cumulatively had an adverse effect on divorce rates and education levels.30 Many found no escape from societal pressures aside from the Indian taverns.31 Lawney recalls that Whitebear was not satisfied with the social and cultural corner urban Indians had been forced into by termination and relocation policies. Having seen the power of the united Indian community at Tacoma and Frank’s Landing, he was convinced that the urban Indian community needed to work together. Bernie was on the verge of becoming an urban Indian activist.

Becoming Bernie Whitebear

In order to show his commitment to Indian activism and to honor his grandfather, White Grizzly Bear, Bernie changed his name from Bernard Reyes to Bernie Whitebear in the summer of 1959.32 He shortened his name to Whitebear so that it would fit on his Boeing ID tags. In addition to honoring his grandfather, it also gave him a distinctly Indian name and reflected his commitment to the Indian community and the advancement of their social conditions. He never forgot his Filipino roots, however, and throughout his life he lent support to Filipino American causes and local Asian American leaders like Bob Santos.

The tribal mixing that resulted in the urban communities from the termination and relocation policies had the side effect of exposing urban Indians to different Native American cultures from across the country. In Tacoma, on Portland Avenue one day Whitebear was introduced to a Powwow, a culturally important festival to Plateau and Plains Indian tribes.33 In it, he witnessed not just Plateau and Plains Indians, but Indians from all over the country celebrating in a way that honored their respective cultures and a new pan-Indianism. He saw the power pan-Indian events could have to help remedy the physical and emotional hardships placed on urban Indians. When he moved permanently to Seattle in 1966 to be closer to work, he sought to mobilize the urban Indian community there in a way he had experienced in Tacoma.34

Within a year of living in Seattle, Whitebear had organized a “National Indian War Dance competition” powwow held at the Seattle Center on May 21st, 1967.35 The powwow featured Indian dancers from tribes across the country and cash prizes totaling more than $1000 to be used for “education purposes” and to “aid needy Indian families.” A piece of Lawney’s artwork, a cedar wood carving, was also awarded to a top dancer. Through the powwow, Whitebear had found a way not just to bring together the urban pan-Indian community, but also a way to express Indian culture and help remedy some of the social and economic problems they were facing. Whitebear held the powwow again in March of 1968 and 1969, attended by members of the Sioux, Nez Perce, Pawnee, Lummi, Makah, and Colville tribes, hosting promotional events, such as rummage sales, to raise community awareness and funds for the powwows.36

In addition to his community involvement in the powwows, Whitebear also took the lead in the campaign against the termination of the Colville tribe in 1969, when valuable timber assets on tribal lands motivated government officials to push for termination to make the timber publicly available. The government offered each Colville Indian $60,000 in exchange for relinquishing their rights to the land, and their tribal identities.37 For many who lived in poverty on the reservation, this was a difficult decision. Whitebear and other Colville leaders saw the priceless value of their heritage, however, and lobbied against termination. What they needed was a firm legal voice protecting the reservation. “They ask, ‘why improve?’ if termination is just around the corner,” Whitebear said in a Seattle Times interview in 1969.38 Through his perseverance the Colville tribe voted unanimously against termination and retained the right to their land and cultural identity.

Fort Lawton and the quest for an Urban Indian Land Base

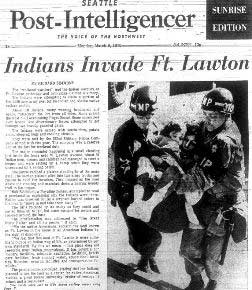

March 8, 1970 marked a new chapter in the ongoing dialogue between the city of Seattle and its urban Indians. “We the Native Americans reclaim the land known as Fort Lawton in the name of all American Indians by right of discovery,” bellowed out Satiacum as he stood next to Whitebear, actress Jane Fonda, and 100 other members of the Seattle urban Indian community as they marched through the entrance of the Army base that the federal government had decided to decommission, now the site of Discovery Park. 39Over the ensuing months, Whitebear, Satiacum, and their newly founded United Indians of all Tribes Federation (UIATF) fought to regain ownership of the land for use as a Native American center. They did so through protests, peaceful invasions, media coverage, and law suits, invoking both the right to the land as designated in their treaties and the need for space and facilities for the growing urban Indian population in Seattle. 40

The Seattle urban Indian population had grown from 700 in 1950 to over 4,000 in 1970, outgrowing the thin social support networks available to them. Ignored by governmental organizations such as the BIA because they no longer lived on reservations41 and marginalized by the City of Seattle due to their smaller population and wider dispersal in comparison to other minority groups,42 they were left to rely on several small charity based organizations such as the American Indian Women’s Service League (AIWSL), led by Pearl Warren, and the newly formed Seattle Indian Health Board, of which Bernie Whitebear stood as the first executive director in 1969.43Bernie writes that the AIWSL was supported “primarily [through] donations and volunteer help” and that the SIHB at the time used “donated space on the 2nd floor of the Marine Public Health Hospital on Beacon Hill… and [was] staffed by volunteer doctors, nurses, and donated pharmaceuticals.”44 Lack of social support systems exacerbated medical and educational problems within the community, and suppressed cultural representation and notions of identity.

When news of Fort Lawton’s surplus status reached Whitebear and Satiacum in 1969, they immediately had the idea of using the land as a cultural center to provide community services to the urban Indian population. They hosted meetings with other leaders of the Indian community and eventually took their case straight to the mayor of Seattle, Wes Uhlman.45 The city, however, seemed set on turning the surplus land into a large natural park, and a recent bill introduced by Washington senators Henry “Scoop” Jackson and Warren G. Magnuson signed into law by President Nixon allowed non-government entities to buy surplus land at 0-50% of the land’s fair market value.46 This would allow the city to acquire the land at zero cost; and powerful community organizations, such as the Magnolia Community Club, worked hard to ensure that an environmental park would be established in the fort’s place.47

The Indian community suddenly found themselves divided. While everyone agreed that building an Indian cultural and heritage center on the surplus fort’s land would benefit the community, leaders favored two distinct approaches to acquire the land. One group, led by Pearl Warren, favored obtaining the land through passive negotiations with city council members after the city of Seattle had been granted the land. Others, led by Whitebear and Satiacum, influenced by the recent takeover of Alcatraz Island by San Francisco urban Indians the previous November of 1969, favored a more militant approach.

Student activist Richard Oakes led the 1969 occupation of Alcatraz Island, also government surplus land, and set the precedent for which Whitebear and Satiacum would follow. Amid the jagged rocks and cold November fog, Oakes read the Alcatraz Proclamation after he and nearly 80 other Indian activists, many students, used boats to reach the island that would be their home for the next several months. “We, the Native Americans, reclaim the land known as Alcatraz Island in the name of all American Indians by right of discovery,” the proclamation began.48 Although neither Whitebear nor Satiacum were present on the island during the takeover, their subsequent near identical proclamation on March 8th at Fort Lawton, and creation of their own United Indians of All Tribes Foundation, named after Oakes’ Indians of All Tribes, revealed their respect for Oakes’ takeover and the precedent he set for invoking treaty rights in the return of surplus government land.

Richard Oakes and the San Francisco urban Indians occupied the island of Alcatraz, sleeping, eating, and bonding with one another, for several months. After an accidental fire burned down their Indian center, they intended to recall an article from their original treaty with the U.S. government that entitled them to any public surplus land previously owned by the tribes to receive title to the island for the creation of a new urban Indian cultural and educational center. The press gobbled up the urban Indian occupation. All over the country and across the Atlantic, newspapers published headlines about the pioneering urban Indian community struggling to preserve their heritage and take care of their community in the hostile urban setting. It didn’t take Whitebear or Satiacum long to catch the headlines and realize the similarities between their situation and that of Alcatraz. They realized that if they wanted to turn Fort Lawton into an Indian cultural center they were going to have to do it through similar militant protests. They had tried negotiations with mayor Uhlman and the Seattle city council and their voice was not heard. In their minds the only way to be heard would be through ‘storming the fort.’ They spent several months planning with other Seattle Indian leaders such as Joe DeLaCruz and Randy Johnson, working out the details of the invasion. By March of 1970, they were organized and ready.49

Responding to the call of the “Moccasin Telegraph,” Satiacum and Whitebear held an informational powwow Sunday evening, the night before the invasion, at the Filipino community hall in south Seattle.50 The crowd was tense but excited. Indians and Indian supporters had traveled from throughout the Pacific Northwest, including Richard Oakes from Alcatraz and the actress Jane Fonda, nationally known for her anti-Vietnam war protests. Whitebear laid out the plans and rules for the next day’s action: “If any of you need alcohol or drugs to get you through this, forget it,” He told the crowd. “I don’t want to make the same mistakes that were made at Alcatraz. I want to win this one.”51

The surf waxed and waned along the rocky beach. The lighthouse stood out among the drab gray military complex, watching over the shores and the forest, holding back in silence the events it saw unfold as the Military Police went about their morning routine. Suddenly, a group of Indian protestors, teepee poles in hand, scrambled over the north fence, making quick work of the barbed wire barrier then pouring into an open field to set up their insurgent base camp. Across the fort at the front entrance another group rushed in, shouting Red Power chants and beating their drums, after being deployed from two half-mile long caravans.52 Within minutes the teepees were erect and Whitebear’s invasion was in full force. Over a hundred activists invaded the fort on the morning of March 8th 1970, with several hundred supporters, Indian and non-Indian, cheering them on and providing food and support, joining in from outside the main entrance. Jane Fonda and Grace Thorpe, daughter of athlete Jim Thorpe, were also there to lend a hand and bring media attention to the takeover.53 But the army moved swiftly. In a coordinated counterattack, troops and MPs moved against the protestors with brute force and intimidation, scattering many and arresting dozens. Whitebear was among those arrested, gaining his freedom the next day.

While the initial insurgency had been broken, the movement was just beginning to blossom. Thanks in part to the support of Jane Fonda and other high profile celebrities, the United Indians of All Tribes invasion received lots of media attention, and awareness about the urban Indians’ bleak plight in Seattle came to light. Whitebear claims that over the ensuing months, over 40 non-Indian organizations in King County came to support the UIATF’s claim to surplus fort land.54 Once released, Whitebear and Satiacum immediately went back to work planning a second invasion. Four days later on March 12, a second wave of Indian activists stormed past the front gate into the fort only to be met with the same resistance by MPs and army soldiers as before.55 Regrouping, for the next three weeks the urban Indians occupied the area just outside the front entrance to Fort Lawton, setting up what they called “Resurrection City,” stocked with food, clothes, and supplies.56 Then on April 2, Whitebear once again led a group of Indian activists beyond the barbed wire fences and into the guarded compound to “reaffirm Indian demands that surplus designated Fort Lawton land be turned over for a multipurpose and education center.”57

Attorneys Gary Bass and Blair Paul encouraged Bernie to open a second front in Washington DC. With their assistance, Whitebear was able to get his United Indians of All Tribes Foundation sponsored by the National Congress of American Indians, the largest national organization of American Indians in the US.58Whitebear then took his case directly to the Bureau of Indian Affairs and to Congress. Flying to the Capitol, he and a small group of UIATF members presented their case to a congressional committee that was considering Senator Jackson’s Fort Lawton Bill. 59

With support from the National Congress of American Indians, Whitebear was able to get a temporary freeze on the Fort Lawton land in November of 1970, which prevented the City of Seattle from obtaining it outright. This forced the city into negotiations with Whitebear and the UIATF and finally gave the Indians a legal footing for their assertion of the property. From July through November of 1971 meetings took place between the two groups as they negotiated who would control the surplus land. On March 29, 1972, two years after the original invasion, the UIATF was granted 20 acres of land on a 99-year lease, renewable at the end of the contract.60 Lawney said that his brother’s victory was the first time in history land had been given back to Indians from the US government.61 Bernie was careful not to call his new agreement with the city a treaty. “It’s not a treaty. The white man doesn’t keep treaties. It’s a legal, binding, agreement.”62

With his Fort Lawton victory, Whitebear had proven the power of a united urban Indian community. For two years the UIATF fought to better the conditions of the urban Indian community through peaceful protests, media awareness, and legal representation. Finally with the land from Fort Lawton, the United Indians of All Tribes could start to build a multi-use cultural center. The end of the battle for the land, however, did not signify the end of the government’s close eye on Whitebear and his Indian activist agenda.

Armed Communist or Pacifist Protestor?

With his newfound fame after the Fort Lawton takeover, Bernie Whitebear also caught the attention of the FBI. The Bureau decided to investigate whether he was “involved in new Left or other militant activities or may merely be sympathetic to Indian Causes.”63 The result was an FBI file 182 pages long that spans from early 1970 through mid- 1975, containing photographs, eye witness testimony, agent reports, newspaper clippings, and UIAT leaflets. Obtained by Trevor Griffey as part of his project on FBI surveillance, the file suggests that the FBI was concerned and confused over whom Whitebear was and what he and his UIATF stood for. In particular federal authorities wanted to know about possible connections to American Indian Movement (AIM) and the Communists Party. 64

“On March 8, 1970,” the FBI file begins, “about 100 Indian demonstrators led by BERNARD WHITE BEAR and ROBERT SATIACUM attempted to peacefully take over Fort Lawton.”65 The FBI had already tracked similar events, notably the previous November 1969’s takeover of Alcatraz Island led by Richard Oakes66. As informants and secret agents tracked Whitebear’s movements over the subsequent months, they wanted to know two things: was he a communist? And was he dangerous?

Their confusion about Whitebear is evident in the conflicting information received from informants, some of whom characterized the protesters as “peaceful”67, while a few alleged otherwise. In one report filed as the Fort Lawton negotiations were underway, an informant made unsubstantiated claims that Whitebear had researched how to build home-made explosive devices in the months preceding the takeover.68 A report from several months later described a meeting of activists who were planning a new round of fish-ins. “He said that this has to be different from other Indian demonstrations,” the secret informant writes of an unidentified Indian leader (not Whitebear) who took part in Alcatraz. “He said that bloodshed is necessary in order to unite the Indians together…[and] if confrontation does not come about, they would have to make one out of necessity.” 69[](whitebear.htm#_edn69) On the next page of the report, the informant writes that Whitebear collected supplies for the Indians who were planning to protest in Puyallup. However, as fall came around and no news articles or reports made it into the FBI file, it appears as if this informant, just like the one who attempted to link Whitebear to a plot to use homemade explosives during the Fort Lawton take-over, may have exaggerated the potential threat in order to pique the FBI’s interest. Most of the reports in the months after Fort Lawton are mundane descriptions of peaceful protests and meetings along with newspaper clippings and leaflets. By mid-1970 a lack of new reports in the file suggests that the FBI concluded that Whitebear and UIAT posed no threat for national security.

The FBI file also records dissent and rivalries within the Seattle urban Indian population during this time. In several reports, informants are quick to write off Whitebear as a mere “publicity speaker”70 who had been rejected by his ethnic Colville Tribe and thus “had to create his own Indian identity through ‘United Indians of All Tribes’ which in effect has been an organization attractive to other Indians like [Whitebear] who have been rejected by their tribes.”71 There is a tone of rivalry in this assessment that suggests that this informant was a tribal member at odds with the pan-Indian strategy UIAT and jealous of the attention that Whitebear was receiving.

In spring 1973, the American Indian Movement (AIM) seized the site of the historical battle of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, beginning an armed standoff with federal authorities that lasted one hundred days and took several lives. The FBI once again investigated Whitebear to discover any possible connections he may have had with AIM. “Around two hundred people attended the rally for Wounded Knee held at Pioneer Square on March 24,” begins a secret agent’s report, listing Whitebear as one of the identified attendees.72 While the report specifically lists “donations of clothing, food, medical supplies, and money… for Wounded Knee participants”73 as the objective of the downtown rally, once again conflicting reports hint at the FBI’s confusion surrounding Whitebear. Some reports listed Whitebear as the leader of the local AIM chapter74, while other informants declared that no local AIM chapter existed75.

Although he was followed at various public events, from a March 8, 1973 Wounded Knee rally in the UW’s Husky Union Building76 to the March 24, 1973 protest in Pioneer Square,77 the lack of any reports on his personal business or interactions with the UIAT seem to hint that the FBI were not very concerned about Whitebear. It is evident from the focus of the reports that the FBI’s main concern during this time was the possible formation of a militant AIM chapter in the Puget Sound Region, training to defend Puyallup and Frank’s landing with bunkers and weapons. Whitebear is only mentioned in the reports due to his Native American heritage, not due to any actions involving him or the UIAT. “On 4-17-73 _________ who is attempting to establish the Seattle Chapter of AIM… is anticipated to enlist up to 100 men and are going to receive training in guerilla warfare, self defense, and how to deal with police anti-riot squads,” reads a secret agent report about the alleged formation of a militant Seattle AIM chapter from information collected from unnamed informants.78 “It has been decided by the people in AIM that Frank’s Landing at Nisqually will be one of the next targets similar to Wounded Knee,” the report continues.79 Given the violence that occurred at Wounded Knee, it should be no surprise that the FBI took any leads on potential future violent outbreaks seriously. However, Whitebear is only mentioned in this report for hosting an Easter ceremony at Fort Lawton, of which two of the participants were Indians from Frank’s Landing.80While the FBI file reveals little about the actions of Whitebear during the 1970s, it serves as an indicator of the US government’s interest in Indian rights activists.

Daybreak Star and the UIATF

Seven years and two months after Bernie Whitebear and over 100 Indian activists and supporters tried to take over the fort, the Daybreak Star cultural and educational center was opened on May 13th 1977.81 The fruition of their hard work, Daybreak Star provided the land base for Whitebear and the United Indians of All Tribes Foundation to execute a number of social, educational, and cultural programs designed to advance the Indian community and increase awareness about Indian culture. The building itself incorporated many Indian artistic elements, such as prominent cedar posts, through the contributions of Lawney Reyes, Bernie’s brother and a nationally acclaimed Indian artist. Reyes also gave the center its name, inspired by the words of Lakota Black Elk,

Then as I stood there two men were coming from the East head first like arrows flying and between them rose the Daybreak Star. They came and gave an herb to me and said ‘with this on earth you shall undertake anything and do it.’ It was the Daybreak Star herb, the herb of understanding…82

The center soon offered programs for adult education, child daycare, cultural development through festivals, heritage workshops, art displays, and technical assistance training.83 By 1985, the UIATF’s capacity had grown to 14 federally funded programs running on a budget of $1.8 million that served more than 1,000 urban Indians.84 Bernie’s love of children and passion for art came through especially with the programs they offered at Daybreak Star.

Although Whitebear never married, Laura always remembered him surrounded by kids. He would frequently take the time to pick at-risk youth off the streets at night, bring them to his house, feed them, and give them a place to sleep.85 Laura remarked that he was everyone’s “dad” and “best friend.”86 At Daybreak Star through programs such as childhood daycare, head start, and GED completion, he sought to meet the needs of the urban Indian youth in Seattle. His culmination of youth support, however, happened off of UIATF grounds in North Seattle through the Labateyah and I’WA’Sil youth homes, which translates from Coast Salish as “positive change.”87

Labateyah and I’WA’SIL offered urban Indian youth a safe place to stay in situations when going home was not an option. Youth suffering from poverty, broken families, and alcohol and drug addictions could go to the shelters to receive a room to live in and any medical care and therapy they needed. Jamie Garner, who worked for the UIATF from the mid- 1980s to the early 2000s as the general consul and a lead grant writer recalled the program’s humble beginnings. After working with Whitebear until the very last moment to finish up the grant for the youth home, Garner got it to the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) office just minutes before the 5:30PM deadline.88 Their stress and worry over the program quickly subdued once they were approved for the several million-dollar grant to be able to purchase a property in Seattle and operate the 24-hour youth home. Garner recalled that at the time it was one of the largest awards in the nation for youth development.89 In addition to substance abuse treatments, the youth homes also offered educational and job training programs as well. Through their years of operation Labateyah and I’WA’Sil helped put thousands of urban Indian youth back on their feet and out of harm’s way.

Indian artwork also featured prominently in UIATF programs and events. Whitebear not only wanted to curate and spread awareness about Indian art—traditional and contemporary— in the larger community, he also wanted to create venues of revenue for Indian artists. Daybreak Star regularly offered drum making, woodcarving, and other artistic workshops open to Indians and the general public. Its nationally acclaimed Sacred Circle art gallery, comprised of traditional and contemporary pieces of Indian art, was boasted by Whitebear as “the largest collection of contemporary major Indian artwork in the nation.”90 The center also hosted an “art mart” on the second Saturday of every month in which artists could sell their work to the public.91 At the time Indian artists were limited in the number of venues available for them to sell their authentic artwork, because much “Native American” art sold had non-Indian origins. Through constant publicity Whitebear was able to extend the art mart’s customer base to include international markets in East Asian countries such as Hong Kong and Japan.92

Dinner Theatre cultural performances were also hosted every first and third Fridays of the month. These programs offered traditional Indian food dinners such as salmon and buffalo bakes and musical and dance performances put on by members of various tribes.93In building relationships with tribes across the country Whitebear and the UIATF also founded the American Indian Tour & Travel agency in 1984 that offered authentic Indian cultural tourism packages to foreign and domestic travelers.94 For centuries, the US government and local state organizations had taken upon themselves to define the cultures of the various North American Indian tribes. But through programs like the UIATF’s art mart and American Indian Tour & Travel, Whitebear sought to place tribal representation back in the hands of tribal members. The travel agency worked with tribes to create tourist packages that included “teepee encampments, salmon and buffalo barbeques, sport fishing, hiking, trail rides, canoe outings, river rafting, Indian foods, archaeological digs” and more.95 In the first year alone, Whitebear noted that it generated more than a quarter of a million dollars in revenue for the tribes. These artwork and cultural programs therefore not only gave tribes and artists newfound recognition, but also helped them earn money and support themselves.

The People’s Lodge

The original plans for the development of the UIATF complex in Discovery Park called for a six-building complex. None received as much media attention as the three building complex People’s Lodge. A grand events and performance hall, the People’s Lodge was to have a 4,500 person auditorium, banquet hall for potlatch ceremonies, an archival storage facility, and a Hall of Ancestors, a place for Indian leaders to be commemorated for all of time.96 As soon as funding began to pour in for the lodge, with the UIATF receiving a million dollar grant from the city in 1976,97 so did complaints from the neighboring Magnolia community.

The Magnolia community wanted to maintain the park’s environmental and natural aesthetics and thought that the 123,000 square foot structure would ruin the park. As the park itself had less than 400 parking spaces they worried that the large events put on at the People’s Lodge would cause a parking overflow into their neighborhood. They also questioned the fiscal viability of the project, worried that a lack of future funding would put a strain on Seattle parks funds and thus taxpayer dollars.98 At times rumors about an Indian casino on the premises also spread through the Magnolia community.99 Whitebear countered by reminding them that the lodge’s construction had been approved by the city in their original land grant, funding for the building would be secured through various state and federal grants, and that it would only be used for 6-8 large cultural events every year.100 Nonetheless, through their negative publicity campaign and hiring of powerful lawyers the Magnolia community was able to freeze construction and funding campaigns under the pretense of a need for a traffic and environmental study.101 A last-minute compromise to reduce the size of the main auditorium from 4,500 seats to 1,500 still had no effect on the Magnolia community’s position and eventually the People’s Lodge lost its one million dollar grant and was prevented from applying for any more at the federal level.

Although disappointed, Whitebear did not give up hope. When a plot of land became available for purchase by the city two years later in south Rainier, the UIATF reworked their original People’s Lodge proposal and expanded it into Tahoma Park, an urban complex that contained office and retail space as well as the cultural amenities of the People’s Lodge. In July of that year, however, their Tahoma Park lost out to the competing company’s plans to turn the area into industrial development when the city council unanimously voted to sell the land to CX Corp.102 Despite the “aesthetically pleasing” and “cultural importance” of Tahoma Park, the city cited CX Corp’s more secure funding, higher offering price, and their promise of creating just under 1,000 new jobs as the reasons they decided to vote against the People’s Lodge.

Still not willing to abandon his plans for the People’s Lodge, Whitebear found an opportunity once again the following year in 1979 when city land near Gasworks Park became available for purchase. This time Tahoma Park was reworked into an urban center complete with a restaurant featuring Indian food, retail shops, a banquet hall, fish hatchery, and small amphitheater, all built with architecture mimicking a Northwest costal village.103 Once again, however, the city voted against Tahoma Park saying that the proposed center’s plans violated park and waterfront usage regulations and instead encouraged UIATF to once again pursue the building of the People’s Lodge on their land at Discovery Park. This ruling put the lodge’s plans on an inescapable hiatus despite Whitebear’s continued lobbying up until his death in 2000.

Gang of Four

Whitebear had a knack for community organization. A concise and pragmatic speaker, he could effectively organize and unite groups of people under his leadership. But his real value as a leader came in knowing his place in the community and recognizing the importance of being a team player and maintaining close personal relationships with as many people as possible. His hard work and humility advanced the social and cultural needs of the urban Indian community not through confrontation and quarrels, but through compromise and understanding. This peaceful approach proved effective in lobbying for UIATF causes and garnering funds to carry out its programs.

The big brother attitude that Laura remembers Bernie having when she grew up stuck with him his whole life. At a time when pan-Indianism was in its infancy and ancient tribal feuds still ran deep, Whitebear often acted as a mediator between tribes in order to achieve tribal unity within the urban Indian community.104 His happy go lucky personality used humor and a smile to work out agreements between different parties and to maintain close ties to many influential local and regional leaders. Laura remembered him as the “go-to” guy within the Indian community, for jobs, family problems, or just to have a friendly lunch. Garner remembers him as being easy to work with and a positive influence in the workplace.105 Daybreak Star became his second home and until his death he could be found working there, well beyond normal office hours. Laura recalls that just months before his death in 2000 from cancer he would leave his doctor’s office with explicit instructions to go home and rest.106 Once in the car however, he would demand to be taken back to Daybreak Star to continue working on new plans for the People’s Lodge or finish up last minute budget details. And because he was her big brother, she had to agree.

His financial lobbying was just as persistent. He understood that in order to maintain the funds UIATF needed to support the urban Indian community he would need to maintain close personal ties with as many influential leaders as possible. He frequently made trips to and campaigned for funds in Seattle, Olympia, and Washington D.C. lobbying for regional and national grants. He also put on a multitude of fundraisers and community events to raise publicity and money for the foundation.

One of the fundraisers his brother Lawney remembers particularly well was when Whitebear came across July 1970 Playboy playmate Carol Willis at a conference in Chicago on problems facing minorities.107 After he learned that she was half-Indian he spoke with her and Hugh Hefner to get her to come out and lend support to the Seattle Indian community. Bernie got Carol to agree to put on a show in Seattle where half of the event’s profits would go towards benefiting the urban Indian community. Lawney was proud of his brother’s hard work to win money for the community and glad that Bernie’s house was too small so that Carol had to stay at his house for the few nights she was in Seattle.

Whitebear’s civic engagement and commitment to peaceful solutions to social problems is also impressive. In late 1979, the YMCA ran into trouble with Indian leaders through their Indian Guide and Indian Princess program.108 The program, promoted by the YMCA as a mentoring program, was criticized for ignorantly imitating Indians and their culture through the use of headbands and war-whoops in the classroom. Instead of calling for the outright removal of the program, Bernie led other minority leaders and met with the YMCA in a series of discussions aimed to culturally sensitize the program so that Indian students would not be offended. In the end, he was able to work with the YMCA to eliminate the Indian stereotypes and turned the experience into a tool for teaching about the various Indian cultures of the United States. Whitebear even provided the YMCA with UIATF educational materials. His compromising approach served to strike harmony in the community between the Indian and non-Indian populations and increased the number of venues in the city’s education system that spread awareness of Indian culture.

In the decades after Fort Lawton, Whitebear took part in a number of task forces and initiatives in the school system aimed at producing fair representation of Indians and Indian culture in Seattle. In 1980 Whitebear joined a 12-person task force to review admission policies for minorities at the UW after critics noted that new policies excluded the fair admission of minorities.109 When West Seattle High School voted to keep their mascot as the “Indians” in 1988, Whitebear urged the school to be careful. “We are talking about symbols of races, of people. If they decide to keep the name, then they are challenged to develop a representation of that culture with dignity,” commented Whitebear.110 Over the years he also took part in several task forces and conferences for Indian art, the Filipino community and other minorities in Seattle, anti-war protests in Latin America under the Reagan administration as well as giving numerous lectures at local schools and colleges about Indian culture and the urban Indian experience.

The culmination of his partnership with other minority leaders in Seattle came in the 1980s with the creation of the Minority Executive Directions Coalition.111 Known informally as the “Gang of Four,” the coalition was formed by a number of minority activists in Seattle and led by Bob Santos, executive director of Inter*Im, an Asian American social service agency, Larry Gossett, executive director of Central Area Motivation Program, an African American social service agency, Roberto Maestas, executive director of El Centro de la Raza, a Latino social service agency, and Bernie Whitebear, executive director of UIATF. Together with the other minority leaders, Whitebear learned that much could be accomplished through unity. The coalition sought to work together to bring common hardships and grievances to the attention of city officials and mass media. They worked together with over 70 community organizations to secure grants for the funding of social services, to carry out programs, and to spread knowledge about the various minorities living in Seattle.112 Bernie Whitebear’s death in 2000 was grieved not just by the Indian community, but by all of the minority communities in Seattle

Legacy

Bernie Whitebear died on Sunday July 16, 2000 after losing a 3-year battle with colon cancer. After he was diagnosed, Governor Gary Locke proclaimed Whitebear “citizen of the decade” and declared the month of October as “Bernie Whitebear Month.”113 His activism on behalf of urban Indians didn’t stop until his last breath and his legacy continues to ignite passion in the minority communities of Seattle to this day. His march on Fort Lawton, development of UIATF and many social services and programs for children and adults, and endless community involvement have changed the way urban Indians live in Seattle. Old Cashmere’s blessing, given when Bernie was only a young child on the reservation, certainly followed him his whole life as he peacefully fought against the multitude of problems facing the urban Indian during his lifetime. In a news article from 1997 he used an image from Star Trek telling the Seattle Times reporter that when he dies, “I’ll become an Indian trekkie, and I’ll go where no Indian trekkie has gone before. And I’ll be looking for other Fort Lawtons out there.”[114

**copyright © Joseph Madsen 2013

**HSTAA 498 Autumn 2012

HSTAA 499 Spring 2013

Special thanks to Laura Wong-Whitebear, Lawney Reyes, and Jamie Garner for sharing memories of Bernie Whitebear, to Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center for allowing access to their archives, and to Trevor Griffey for sharing the FBI file.

1 Reyes, Lawney. Bernie Whitebear: An Urban Indian’s Quest For Justice pp. 164

2Ibid. pp. 11-15. Reyes describes the history of the tribe as having been negatively influenced by American and Canadian mining, logging, fishing and other resource extract industries, legislation and treaties that shrunk the size of their land and prevented their migration to tradition hunting grounds, smallpox and other diseases which their tribe had no immunity to, and early Christian missionary attempts that criticized and prevented them from practicing their traditional beliefs and ceremonies.

3 Ibid. pp. 14.

4 Ibid. pp. 3.

5 Ibid. pp. 8

6 Personal Interview with Lawney Reyes, November 12, 2012. Note: his interview and the others I conducted with Laura Wong-Whitebear and Jamie Garner were recorded with written notes and any emphasis given is my own.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid. pp. 19

10 Ibid. pp. 38

11 Ibid. pp. 39

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid. pp. 40

14 Ibid. pp. 42

15 Ibid. pp. 61

16 Personal Interview with Laura Wong-Whitebear, October 31, 2012

17 “The Fish-in Protests at Frank’s Landing” by Gabriel Chrisman. Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project.

18 Ibid.

19 Personal Interview with Lawney Reyes, November 12, 2012.

20 Gabriel Chrisman, “The Fish-in Protests at Frank’s Landing”Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project.

21 Reyes Bernie Whitebear An Urban Indian’s Quest for Justice pp. 75

22 Gabriel Chrisman, “The Fish-in Protests at Frank’s Landing”Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid. 71

25 Police report dated to June 18, 1973 FBI file

26 Reyes, _Bernie Whitebear An Urban Indian’s Quest for Justice_pp. 72

27 Like a Hurricane pp. 7

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid pp. 8

30 Reyes, _Bernie Whitebear An Urban Indian’s Quest for Justice_pp. 83

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid. Pp. 73

33 Ibid. Pp. 83

34 Ibid. Pp. 86

35 “Indian-Dance Winner to Get Whale Carving” Seattle Times May 5, 1967

36 “Indians Plan Rummage Sale” Seattle Times February 16 1968 and “War Dance Presented” Seattle Times March 10th 1969

37 Reyes, _Bernie Whitebear An Urban Indian’s Quest for Justice_pp. 87

38 “Jackson’s Bill For Indians is Criticized” Seattle Times May 4, 1969

39 “Indians ‘Invade’ Army Posts” Seattle Times March 9, 1970

40 Coll-Peter Thrush, The Crossing Over Place: Urban and Indian Histories in Seattle. PhD diss. University of Washington, 2002. pp 305, 315

41 Whitebear, Bernie “A Historical Perspective” 1994 http://www.unitedindians.org/about_history_bernie.html

42 Thrush writes that in 1970 Seattle African Americans outnumbered urban Indians by almost 10 to 1 and that their concentration in the central district eased the implementation of social services. Pp. 315

43 Whitebear “A Historical Perspective” 1994

44 Ibid.

45 Reyes, _Bernie Whitebear An Urban Indian’s Quest For Justice_pp. 99

46 Lossom Allen, “By Right of Discovery: United Indians of All Tribes Retakes Fort Lawton, 1970”. Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project.

47 Reyes, _Bernie Whitebear An Urban Indian’s Quest For Justice_pp. 99

48 Like a Hurricane pp. 28

49 Reyes, _Bernie Whitebear An Urban Indian’s Quest For Justice_pp. 98

50 Whitebear, “A Historical Perspective” 1994

51 Reyes, _Bernie Whitebear An Urban Indian’s Quest For Justice_pp. 100

52 Whitebear, “A Historical Perspective” 1994 and Lossom Allen, “By Right of Discovery: United Indians of All Tribes Retakes Fort Lawton, 1970”. Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project.

53 Reyes, _Bernie Whitebear An Urban Indian’s Quest For Justice_pp. 100

54 Whitebear, “A Historical Perspective” 1994

55 Lossom Allen, “By Right of Discovery: United Indians of All Tribes Retakes Fort Lawton, 1970”. Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project.

56 Ibid.

57 Don Hannula, “Indians Again Try to Occupy Fort Lawton; 80 Detained,” Seattle Times, April 2, 1970, sec. A, p. 1

58 Lossom Allen, “By Right of Discovery: United Indians of All Tribes Retakes Fort Lawton, 1970”. Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project.

59 Whitebear, “A Historical Perspective” 1994

60 Whitebear, “A Historical Perspective” 1994

61 Personal Interview with Lawney Reyes, November 12, 2012.

62 Shelby Scates, “Whitebear Leads the Indians to Victory in Ft. Lawton Battle,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, December 5, 1971, p.5

63 Search Warrant of Bernie Whitebear to SAC, Seattle dated 7/9/73 FBI file

64 Bernard Reyes FBI file (100-SE-30352), courtesy Trevor Griffey.

65 “RE Demonstration By Indians Fort Lawton” dated March 11, 1970 FBI file

66 For more information on the occupation of Alcatraz, see “Like a Hurricane” (1996)

67 “RE Demonstration By Indians Fort Lawton” dated March 11, 1970 FBI file

68 “UNSUB; Series of Bombings Seattle, Washington” dated 5/4/70 FBI file

69 Informant meeting letter beginning “On Sunday August 23, 1970” dated Monday August 24 1970 FBI file

70 “Planned Protest March On Washington DC By American Indians October 29- November 7, 1972” FBI file

71 “To SAC, Seattle” dated 1/11/73 FBI file

72 “Wounded Knee Rally. Pioneer Square Seattle Washington” dated March 25, 1973 FBI file

73 Ibid.

74 “UW Rally for Wounded Knee” dated March 10, 1973 FBI file

75 “American Indian Movement (AIM) Extremist Matters – American Indian Activities” dated 1/9/73 FBI file

76“UW Rally for Wounded Knee” dated March 10, 1973 FBI file

77“Wounded Knee Rally. Pioneer Square Seattle Washington” dated March 25, 1973 FBI file

78 “Information Concerning Organization of AIM, Seattle, Washington” dated April 23, 1973 FBI file

79 Ibid. Pp. 2

80 Ibid. Pp. 6

81 “Indian Center to be Dedicated” Seattle Times May 11, 1977

82 Reyes, Bernie Whitebear An Urban Indian’s Quest For Justice. pp. 112-113

83 “Indian Center to be Dedicated” Seattle Times May 11, 1977

84 “Tribes Travel Upwards From Fort Lawton” Seattle Times March 4, 1985

85 Personal Interview with Laura Wong-Whitebear October 31, 2012.

86 Ibid.

87 Personal Interview with Jamie Garner November 16, 2012.

88 Ibid.

89 Ibid.

90 “Tribes Travel Upwards From Fort Lawton” Seattle Times March 4, 1985

91 “Giving a Gift of Indian Crafts” Seattle Times December 21, 1985

92 “Indians Selling In Asia” Seattle Times October 26, 1978

93 “Going to Dinner at Daybreak Star” Seattle Times June 8, 1980

94 “Indians Hope to Guide Guests to Reservations” Seattle Times June 12, 1984

95 Ibid.

96 “$48 Million Discovery Park Lodge Put On Hold” Seattle Times February 24, 2006

97 “Evans signs measure for Indian Cultural Center at Discovery Park” Seattle Times April 16,1976

98 “Will Indians Be Allowed To Put Arena In Park?” Seattle Times November 2, 1976

99 Personal Interview with Laura Wong-Whitebear October 31, 2012

100 “Indians Denied Grant for Discovery Park Arena” Seattle Times December 14,1976

101 “Action Delayed on Discovery Park Arena” Seattle Times December 2, 1976

102 “Council Votes to Sell Stadium to Photo Firm” Seattle Times July 18, 1978

103 “City’s Commitment to aid 20,000 Indians” Seattle Times November 16, 1979

104 Personal Interview Laura Wong-Whitebear October 31, 2012

105 Personal Interview Jamie Garner November 16, 2012

106 Personal Interview Laura Wong-Whitebear October 31, 2012

107 Personal Interview with Lawney Reyes November 12, 2012.

108 “‘Indian Guide’ Program Offensive, says Indian Group” Seattle Times December 7, 1979

109 “Task Force to Look at Minority Policies” Seattle Times August 21, 1980

110 “West Seattle May Lose ‘Indians’” Seattle Times November 8, 1988

111 Santos Humbows, Not Hotdogs! pp. 64

112 Ibid. pp. 65

113 Congressional Senate Record S12056 November 7, 1997

114 “Facing End, Activist Reflects on Life’s Victories” Seattle Times December 2, 1997