January 25, 2022

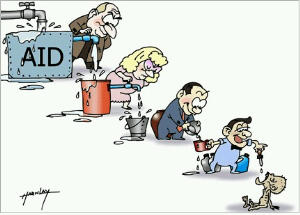

[VIDEO] Phantom Aid: Money allocated to countries that ends up funding INGOs

International NGOs are expensive. They are usually run from their headquarters in expensive cities in high income countries like Washington DC, New York, Boston or Seattle, where the costs are very high compared to low-income countries. They charge overhead and indirect costs for their offices and overall organizational administration which are not related to the specific grant or contract. And the overhead can be more than half the entire project budget with an average of about 15-30% of these total budgets. The INGO offices are often quite expensive, and the administrative staff typically earn high salaries for the overall management of the NGO.

In addition to the overhead, the NGOs have substantial headquarter staff who provide either technical or financial management support just for the specific project. They are also highly paid and take additional funds from the project budget. They supervise the extensive and stringent programmatic and financial reporting requirements from the donors. These staff consume another 15-30% of the total grant substantially allocated to be given to low and middle-income countries. So, overall, between 30-60% of the total budget of many global health aid projects never even leave the headquarters of the INGO.

See video:

Furthermore, within the low-income country which is supposed to be the beneficiary of the aid, the INGO typically has well-appointed, nicely equipped offices with technical and administrative staff whose salaries and benefits greatly exceed that of the government counterparts, often about 10 times the government salaries. They typically have fleets of new and expensive 4×4 vehicles to oversee project activities and attend meetings with their government counterparts and other NGOs. And a big piece of INGO activities involves short term trainings of government health workers including paying per diems to these government health workers that amount to up to a third of their monthly salary per day of training. The INGOs also need an army of financial human resources and data analysts to manage the projects and some of these trainings are quite effective, but others are less so, especially because the ministry of health budgets are so grossly inadequate that they result in poor working conditions, poverty salaries and low morale. It is no surprise that the ministry of health officers often struggle to do the activities that they are trained to do by the INGOs.

In Mozambique, for instance, the total PEPFAR budget during 2016 was approximately $450M, almost as equal as the ministry of health budget of $472M. And although the PEPFAR budget covered the cost of the much needed and expensive HIV viral load testing, and equipment and medicines and supplies, all used by the MOH, the bulk of the 450M went to the INGOs into the very large PEPFAR technical & administrative staff and their associated cost. Many highly trained technical staff from the ministry of health left their jobs to take benefit of the much higher salaries and benefits and other working conditions of the INGOs and the PEPFAR offices, creating huge gaps within the critical positions in the MOH throughout the country. The MOH leadership has complained bitterly about this internal brain drain, but little has been done.

According to my sources within the MOH, less than 5% of the total PEPFAR budget went directly to the ministry of health where the funding needs has been the greatest. The exact amount of phantom aid in a country like Mozambique is difficult to ascertain. But my guess is that the true value of the aid to the MOH calculated by the proportion of what the total program budget would likely have been funded had it been managed by the MOH is about 20-40%. So, even if the MOH lost 10-20% of the donor money through, say, mismanagement and corruption (which by the way also happens in INGOs), this would be far-far less than the legal loss of 60-80% of the value of this through the phantom aid process.

Phantom aid also perpetuates inequality by creating a class of elite nationals and ex-patriots whose donor funded salaries push up the overall cost of housing, food, vehicles. The INGO vehicles are a big contributor to the traffic jam and environmental crises. So, these characteristics of global health aid are apparent o many well-intentioned INGOs and global health workers but they are reluctant to examine this diversion of funds in their agencies or to themselves; or to examine their own roles in perpetuating inequality. This is not an argument to reduce global health aid to the low-income countries, they need support and solidarity and financial resources from the global North. But there are much better ways to work with the MOH to improve systems for the poor and disadvantaged. We could start with direct contributions to the MOH whose capable staff are likely to use these contributions in a much more efficient manner including hiring out NGOs and then they can decide which NGOs to work with.

By: Steve Gloyd