Meet the Board tours have been a mainstay of the NHS summer for many years. Private gardens showcase the passion and dedication of their creators, often including unusual quirks of interests.

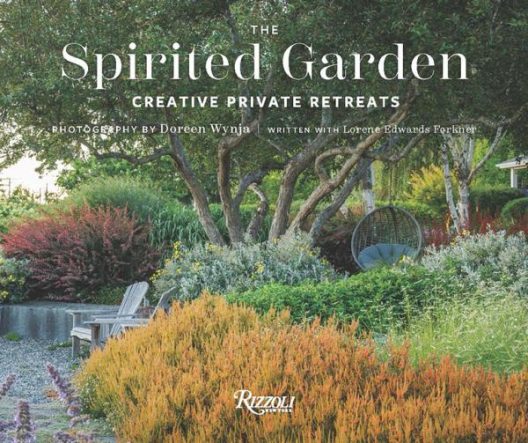

Capturing this fervor and the distinctive visions of several Washington and Oregon gardens is The Spirited Garden: Creative Private Retreats. Photographed by Doreen L. Wynja, and written with Lorene Edwards Forkner, this is one of the most engaging private garden tour books I’ve seen.

The photographs are stunning as you would expect. But they also tell stories. This can be a gardener peeking through foliage, another resting in a hammock while playing with a frisky cat, or the borrowed landscape of a meadow, distant forest, and lone hiker on a two-page, full bleed spread.

The photographs are stunning as you would expect. But they also tell stories. This can be a gardener peeking through foliage, another resting in a hammock while playing with a frisky cat, or the borrowed landscape of a meadow, distant forest, and lone hiker on a two-page, full bleed spread.

The text, both as an introduction to each chapter, and as caption to the photographs, was the real surprise. Wynja and Forkner create a lively discourse with their subjects, teasing out little snippets of story that make you want to know the gardeners, not just their gardens.

For long-time NHS members, some of these gardeners will be familiar. Most poignant is the chapter about the late Pat Riehl, former president of NHS, who with her husband Walt established a stumpery and fern garden on Vashon Island. Gillian Mathews also has a long history with the NHS, and her cozy garden makes you want to stop in for tea – or maybe a glass of wine.

Ann Amato’s exuberant garden blurs the distinction between indoors and out with over five hundred houseplants, many spending their summers outside. There is vibrant plant energy in almost every space from kitchen to bathroom to basement. At the time of this writing (early August 2025), I’m looking forward to her upcoming NHS webinar on hardy begonias.

Wynja’s selection of this and other overflowing gardens is understandable after seeing her own home in the final chapter. Having a “need for visual stimulation,” she collects foliage plants (only a few with flowers), many pots (some intended for that purpose, while others not), and the many, many tools of the gardener. As described in one caption, this is “cramscaping!”

Reviewed by: Brian Thompson on August 12, 2025

Published in Garden Notes: Northwest Horticultural Society, Fall 2025

She is very proud of the order she brings to a garden, “acculturating the unruly flowers” and is often found edging gardens of all types. Because of slow growth, she rarely outgrows her intended size. The use of boxwood for topiary dates back to antiquity and has been especially popular in European cultures since the Renaissance.

She is very proud of the order she brings to a garden, “acculturating the unruly flowers” and is often found edging gardens of all types. Because of slow growth, she rarely outgrows her intended size. The use of boxwood for topiary dates back to antiquity and has been especially popular in European cultures since the Renaissance. In the last 10 years, the publishing of houseplant books has boomed; this is one of the best. The many selections are skillfully described in both text and photos. Each entry, and the extensive introduction (100 pages!), provide all the details you’ll need. Lighting, temperature, feeding, water, soil or substrate are precisely and easily explained. It’s hard to go wrong.

In the last 10 years, the publishing of houseplant books has boomed; this is one of the best. The many selections are skillfully described in both text and photos. Each entry, and the extensive introduction (100 pages!), provide all the details you’ll need. Lighting, temperature, feeding, water, soil or substrate are precisely and easily explained. It’s hard to go wrong. Many contemporary people and places already doing that work appear in this book. Each chapter describes challenges and successes relating to a different plant, mostly vegetables. Throughout Alexander argues against the planting of monocultures, which are particularly likely to be afflicted by disease, and against the practices of the giant seed companies that promote those monocultures and control new cultivars by patenting them.

Many contemporary people and places already doing that work appear in this book. Each chapter describes challenges and successes relating to a different plant, mostly vegetables. Throughout Alexander argues against the planting of monocultures, which are particularly likely to be afflicted by disease, and against the practices of the giant seed companies that promote those monocultures and control new cultivars by patenting them. Some of these were known in ancient times but forgotten, only to be rediscovered much later. For example, the famous Fibonacci sequence, named after a 13th century Italian, is really much older, dating back to Sanskrit poets in India in the 3rd century BCE.

Some of these were known in ancient times but forgotten, only to be rediscovered much later. For example, the famous Fibonacci sequence, named after a 13th century Italian, is really much older, dating back to Sanskrit poets in India in the 3rd century BCE. Wild in Seattle is a collection of the Street Smart Naturalist newsletters Williams writes weekly, each two or three pages long. Its three sections – “Geology,” “Fauna,” and “Flora and Habitat” – lay out various discoveries Williams has made patrolling the city on foot. He emphasizes that one need not be a professional scientist to enjoy these encounters.

Wild in Seattle is a collection of the Street Smart Naturalist newsletters Williams writes weekly, each two or three pages long. Its three sections – “Geology,” “Fauna,” and “Flora and Habitat” – lay out various discoveries Williams has made patrolling the city on foot. He emphasizes that one need not be a professional scientist to enjoy these encounters. One of the newest and most unusual books in the Miller Library is The Vasculum or Botanical Collecting Box, which tells the history of these scientific tools, beginning in the 1700s. Makers of early examples experimented with different construction materials, with tinplate becoming the most common, although some were made of wood, canvas, or other metals.

One of the newest and most unusual books in the Miller Library is The Vasculum or Botanical Collecting Box, which tells the history of these scientific tools, beginning in the 1700s. Makers of early examples experimented with different construction materials, with tinplate becoming the most common, although some were made of wood, canvas, or other metals. In This Infant Adventure Christian Lamb takes the reader to ten of these offspring. Her focus is on the commercial purposes of the gardens and especially on the botanical explorers who worked at and adventured from them. For each garden Lamb describes its history, often noting the tension between those who saw the goal as a pleasure garden only and those who sought scientific collection methods and commercial uses.

In This Infant Adventure Christian Lamb takes the reader to ten of these offspring. Her focus is on the commercial purposes of the gardens and especially on the botanical explorers who worked at and adventured from them. For each garden Lamb describes its history, often noting the tension between those who saw the goal as a pleasure garden only and those who sought scientific collection methods and commercial uses. We love all our new books, but some stand out. The Journey of Neil, the Great Dixter Cat, presented to the library by Fergus Garrett during his September visit to Seattle, tells the fascinating story of a kitten from the streets of Kabul, Afghanistan who came to be a popular fixture at the well-known garden in Sussex. Written by Honey Moga, the kitten’s naming, personality, friendships with Fergus and others at Great Dixter, and adventures with the garden’s resident dachshunds, Conifer and Miscanthus are all presented in Dabin Han’s lively illustrations, along with key elements of the history of Afghanistan. Check it out!

We love all our new books, but some stand out. The Journey of Neil, the Great Dixter Cat, presented to the library by Fergus Garrett during his September visit to Seattle, tells the fascinating story of a kitten from the streets of Kabul, Afghanistan who came to be a popular fixture at the well-known garden in Sussex. Written by Honey Moga, the kitten’s naming, personality, friendships with Fergus and others at Great Dixter, and adventures with the garden’s resident dachshunds, Conifer and Miscanthus are all presented in Dabin Han’s lively illustrations, along with key elements of the history of Afghanistan. Check it out! Whenever overwhelmed by news of a new climate-related disaster, John Hanson Mitchell buys a new rose bush. He explains it as a philosophical statement of resistance.

Whenever overwhelmed by news of a new climate-related disaster, John Hanson Mitchell buys a new rose bush. He explains it as a philosophical statement of resistance.