William Curtis (1746-1799) was born in Alton, England, about 50 miles southwest of central London. His father was a Quaker tanner. He was apprenticed to his grandfather, the local apothecary, at age 14, but he was more interested in the natural history learned from the groom at the inn next door.

Curtis moved to London, becoming by his mid-20s a partner in an apothecary practice, but he soon gave this up. At first, he worked at the Chelsea Physic Garden as a “demonstrator of botany”. Next, he established his own garden in London, open by subscription. He gave lectures to members along with seeds and plants from the 6,000 species of plants he grew.

Curtis collected a library of 250 books and was an active writer, publishing papers over a range of natural history subjects. This included an attempt to write the flora of all the plants native within a ten-mile radius of London as he was an early conservationist and concerned with the loss of plant habitats as the city grew.

Curtis collected a library of 250 books and was an active writer, publishing papers over a range of natural history subjects. This included an attempt to write the flora of all the plants native within a ten-mile radius of London as he was an early conservationist and concerned with the loss of plant habitats as the city grew.

The biography of Curtis is at the core of “A Celebration of Flowers.” Author Ray Desmond tells how this effort to produce a London flora was never completed because of repeated delays in production and disinterest from potential buyers, who were more interested in exotic plants than those they regarded as local weeds.

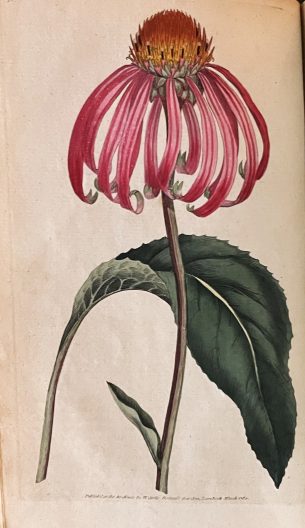

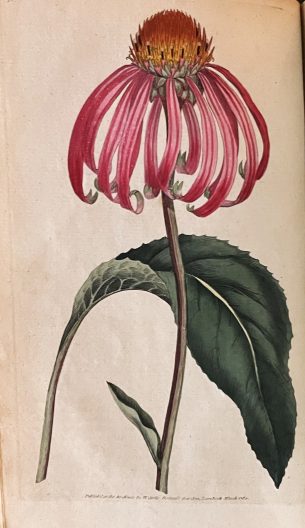

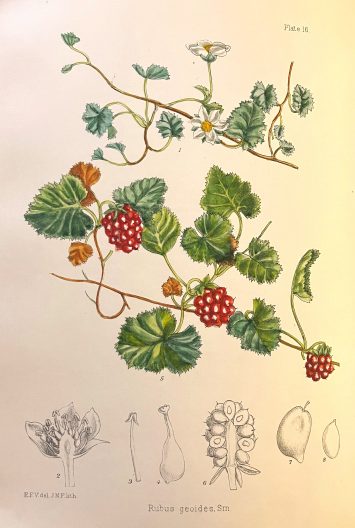

Curtis was instead encouraged to begin a monthly magazine with illustrations of garden plants, both native  and long-established. The focus was on the quality of the hand-colored prints, including this Echinacea purpurea (labeled as Rudbeckia purpurea) from the first issue. The text, often borrowed from others, was supportive but not extensive.

and long-established. The focus was on the quality of the hand-colored prints, including this Echinacea purpurea (labeled as Rudbeckia purpurea) from the first issue. The text, often borrowed from others, was supportive but not extensive.

The new publication was well-received. What is now known as “Curtis’s Botanical Magazine” began with a circulation of 3,000 each month, but was increased to 5,000 because of demand. Most amazing, it is still being published 237 years later! Many of the 20th and all of the 21st century issues are available in the Miller Library.

A listing of the artists that contributed to “Curtis’s Botanical Magazine” includes most of the best botanical illustrators in Britain. All of them were men until the 1870s, but after that it has mostly been women. The illustrations were almost always drawn from live plants and were hand-colored until 1948.

At the beginning, 30 people engaged in coloring of the plates printed from this original art. Typically, women and young children were doing this very repetitive work. Ray Desmond notes the “Magazine was hand-colored until 1948, a process in the later years in a factory setting with each worker coloring one part of one plate over and over again, before passing it on to the next worker.

Of this dreary process, Desmond continues, “With a relentless pressure of work it was no mean achievement that a creditable level of care and finish was maintained by most colourists. Where there were lapses it should be remembered that the low wages paid did not encourage them to excel.”

Reviewed by: Brian Thompson on February 23, 2024

Excerpted from the Spring 2024 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

“A Herbal of Iraq” provides brief description of 50 plants used in that country’s ethnobotanical medicine. Shahina A. Ghazanfar, editor of “Plants of the Qur’ān”, is co-editor along with Chris J. Thorogood and Rana Ibrahim.

“A Herbal of Iraq” provides brief description of 50 plants used in that country’s ethnobotanical medicine. Shahina A. Ghazanfar, editor of “Plants of the Qur’ān”, is co-editor along with Chris J. Thorogood and Rana Ibrahim. Conrad Loddiges (1738-1826) was born in the Kingdom of Hannover, now part of northern Germany, but after training in Holland, he moved at age 19 to the village of Hackney, now part of northeast London. He purchased a seed company, eventually turning this into Loddiges Nursery, one of the most prominent nurseries in Europe.

Conrad Loddiges (1738-1826) was born in the Kingdom of Hannover, now part of northern Germany, but after training in Holland, he moved at age 19 to the village of Hackney, now part of northeast London. He purchased a seed company, eventually turning this into Loddiges Nursery, one of the most prominent nurseries in Europe. Curtis collected a library of 250 books and was an active writer, publishing papers over a range of natural history subjects. This included an attempt to write the flora of all the plants native within a ten-mile radius of London as he was an early conservationist and concerned with the loss of plant habitats as the city grew.

Curtis collected a library of 250 books and was an active writer, publishing papers over a range of natural history subjects. This included an attempt to write the flora of all the plants native within a ten-mile radius of London as he was an early conservationist and concerned with the loss of plant habitats as the city grew. and long-established. The focus was on the quality of the hand-colored prints, including this Echinacea purpurea (labeled as Rudbeckia purpurea) from the first issue. The text, often borrowed from others, was supportive but not extensive.

and long-established. The focus was on the quality of the hand-colored prints, including this Echinacea purpurea (labeled as Rudbeckia purpurea) from the first issue. The text, often borrowed from others, was supportive but not extensive. “Philip Miller (1691-1771) was the most distinguished and influential British gardener of the eighteenth century.” This high praise is by Hazel Le Rougetel, the author of “The Chelsea Gardener,” a biography of Miller. She explains this admiration is “for his practical skill in horticulture and his wide botanical knowledge of cultivated plants.”

“Philip Miller (1691-1771) was the most distinguished and influential British gardener of the eighteenth century.” This high praise is by Hazel Le Rougetel, the author of “The Chelsea Gardener,” a biography of Miller. She explains this admiration is “for his practical skill in horticulture and his wide botanical knowledge of cultivated plants.” reforestation. In “

reforestation. In “ He had hoped to complete an extensive and comprehensive book on gardening, but only small portions were published during his life. Two of these can be found in “Directions for the Gardiner and other Horticultural Advice,” edited by Maggie Campbell-Culver.

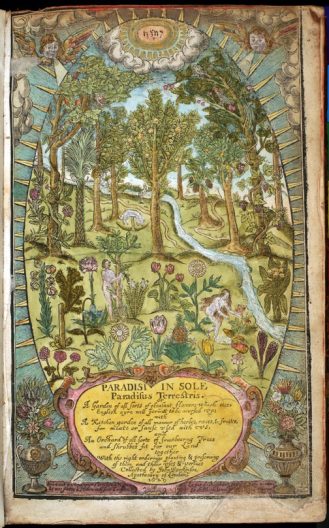

He had hoped to complete an extensive and comprehensive book on gardening, but only small portions were published during his life. Two of these can be found in “Directions for the Gardiner and other Horticultural Advice,” edited by Maggie Campbell-Culver. Anna Parkinson is possibly a descendant of John Parkinson (1567-1650), the apothecary and gardener noted for being the first to write in English about ornamental gardening. While the ancestral line is uncertain, Anna pursues John’s story with the zeal of a descendant in “Nature’s Alchemist: John Parkinson, Herbalist to Charles I”.

Anna Parkinson is possibly a descendant of John Parkinson (1567-1650), the apothecary and gardener noted for being the first to write in English about ornamental gardening. While the ancestral line is uncertain, Anna pursues John’s story with the zeal of a descendant in “Nature’s Alchemist: John Parkinson, Herbalist to Charles I”. royal position as noted in the Anna Parkinson’s sub-title.

royal position as noted in the Anna Parkinson’s sub-title. in that her scientific vigor was recognized when she was accepted as a Fellow in the Linnaean Society of London in 1906, a prestigious group of botanical scientists that require a two-thirds approval of membership to be accepted.

in that her scientific vigor was recognized when she was accepted as a Fellow in the Linnaean Society of London in 1906, a prestigious group of botanical scientists that require a two-thirds approval of membership to be accepted. The Falkland Islands, or Islas Malvinas, are an isolated archipelago east of South America in the south Atlantic Ocean. Uninhabited when discovered by European powers in the 1600s, dispute over its control has continued for centuries, including a deadly war between Argentina and Britain as recently as 1982. The flora is quite isolated, too, with no native trees, and the largest shrubs only reaching seven feet tall.

The Falkland Islands, or Islas Malvinas, are an isolated archipelago east of South America in the south Atlantic Ocean. Uninhabited when discovered by European powers in the 1600s, dispute over its control has continued for centuries, including a deadly war between Argentina and Britain as recently as 1982. The flora is quite isolated, too, with no native trees, and the largest shrubs only reaching seven feet tall. Librarians are often called upon to solve mysteries, and we enjoying hearing the stories of triumphs by our colleagues. One of my favorites is the story of Mary Gunn (1899-1989), a librarian at the Botanical Research Institute in Pretoria, South Africa. She had a special interest in the history of botany and botanical illustration.

Librarians are often called upon to solve mysteries, and we enjoying hearing the stories of triumphs by our colleagues. One of my favorites is the story of Mary Gunn (1899-1989), a librarian at the Botanical Research Institute in Pretoria, South Africa. She had a special interest in the history of botany and botanical illustration. ct few in “Specimens,” but why this was done anonymously is unknown. The book received high praise at the time, with a copy being given to Queen Victoria. There were only 110 printed, and those soon became rare collector’s items.

ct few in “Specimens,” but why this was done anonymously is unknown. The book received high praise at the time, with a copy being given to Queen Victoria. There were only 110 printed, and those soon became rare collector’s items.