Eccentrics have been described as having “varieties of physical and behavioural abnormality that occupied ‘contested space at the juncture of madness and sanity’” (pp. 1-2). In English Garden Eccentrics: Three Hundred Years of Extraordinary Groves, Burrowings, Mountains and Menageries Todd Longstaffe-Gowan shows how a group of English men and women in the seventeenth to twentieth centuries used their gardens to express and develop their eccentricities. That means, of course, that in addition to describing their wonderfully diverse gardens, he also tells us many juicy bits about the gardeners’ lives.

Eccentrics have been described as having “varieties of physical and behavioural abnormality that occupied ‘contested space at the juncture of madness and sanity’” (pp. 1-2). In English Garden Eccentrics: Three Hundred Years of Extraordinary Groves, Burrowings, Mountains and Menageries Todd Longstaffe-Gowan shows how a group of English men and women in the seventeenth to twentieth centuries used their gardens to express and develop their eccentricities. That means, of course, that in addition to describing their wonderfully diverse gardens, he also tells us many juicy bits about the gardeners’ lives.

It’s worth noting that “garden” in this case involves many things in addition to plants, and sometimes not many plants at all. The book presents twenty-one of these oddities, each with excellent illustrations: drawings, paintings, woodcuts, photographs – all very worth examining.

At Hoole House in Cheshire the focus falls on the garden itself more than the owner, Lady Broughton. She had come to Hoole House after she separated from her husband, Sir John Delves Broughton, 7th Baronet, in 1814. (Titles abound among these gardeners.) Separating from your husband and setting up your own household was eccentricity enough.

After her arrival, Lady Broughton had constructed a large and very tall rock garden covered with alpine plants and laid out to resemble shapes of the Swiss mountains at Chamonix, including the glacier at their base. A contemporary illustration from Gardener’s Magazine is paired in the book with a pen and ink drawing of the mountains to make clear how exactly the garden rocks matched the outline of the mountains. That the garden’s representation of the glacier made the area feel cool even in summer, as one visitor insisted, readers can only imagine.

One garden with a primary focus on plants was Viscount Petersham’s in Derbyshire. Petersham, a companion of the Prince Regent who became George IV, was described in 1821 as “’the maddest of all the mad Englishmen’” (p. 83). After he married a beautiful but scandalous actress, he developed his garden to entertain her – in the country, far from public view. A central project of this new garden became the transplanting of topiaries and other trees. William Barron, Petersham’s Scottish gardener, learned how to transplant mature trees successfully, and by 1850 had moved hundreds onto the property. “It was as though the earl were devising every form of horticultural diversion possible to keep his wife from pining for an existence beyond the bounds of her prison paradise” (p. 87).

The illustrations show that at least some of his many topiaries had shapes much more varied and complex than the more typical birds. Yews shaped like enormous mushrooms, tall columns, even a cave-like arbor were enclosed in a long, undulating hedge. One visitor responded enthusiastically to the prospect, reporting: “’we actually threw our body down upon the soft lawn in an ecstasy of delight’” (p. 96).

In one final glimpse of another garden, Lamport Hall exhibited the now-ubiquitous garden gnome gone mad: many dozen tiny ceramic gnomes were scattered throughout.

Well researched and lavishly illustrated, English Garden Eccentrics yields both copious information and a great deal of entertainment.

Reviewed by Priscilla Grundy in the Leaflet, June 2023, Volume 10, Issue 6.

Martin Lemelman is the author/illustrator of “The Miracle Seed” and uses a style similar to comic books to tell his story. The Judean date palm, a cultivar of Phoenix dactylifera, was an important tree for its sweet fruit, medicinal properties, and cultural significance to the Jewish people. Following the bloody put-down of Jewish revolt between 66-74 CE, many of the groves were destroyed by the Romans. In the centuries that followed, a combination of factors led to the tree’s extinction.

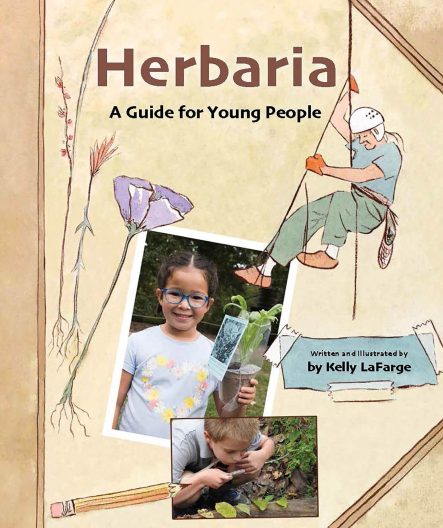

Martin Lemelman is the author/illustrator of “The Miracle Seed” and uses a style similar to comic books to tell his story. The Judean date palm, a cultivar of Phoenix dactylifera, was an important tree for its sweet fruit, medicinal properties, and cultural significance to the Jewish people. Following the bloody put-down of Jewish revolt between 66-74 CE, many of the groves were destroyed by the Romans. In the centuries that followed, a combination of factors led to the tree’s extinction. “Herbaria: A Guide for Young People” is a delight. Written and illustrated by Kelly LaFarge, this book blends a mix of drawings and photographs along with lift-up flaps and fold out pages to introduce these critical institutions to an audience that appreciates an interactive experience.

“Herbaria: A Guide for Young People” is a delight. Written and illustrated by Kelly LaFarge, this book blends a mix of drawings and photographs along with lift-up flaps and fold out pages to introduce these critical institutions to an audience that appreciates an interactive experience. Eccentrics have been described as having “varieties of physical and behavioural abnormality that occupied ‘contested space at the juncture of madness and sanity’” (pp. 1-2). In English Garden Eccentrics: Three Hundred Years of Extraordinary Groves, Burrowings, Mountains and Menageries Todd Longstaffe-Gowan shows how a group of English men and women in the seventeenth to twentieth centuries used their gardens to express and develop their eccentricities. That means, of course, that in addition to describing their wonderfully diverse gardens, he also tells us many juicy bits about the gardeners’ lives.

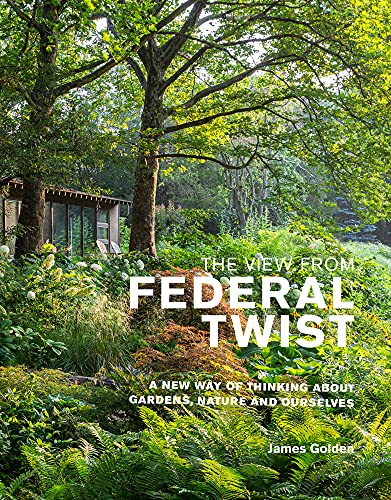

Eccentrics have been described as having “varieties of physical and behavioural abnormality that occupied ‘contested space at the juncture of madness and sanity’” (pp. 1-2). In English Garden Eccentrics: Three Hundred Years of Extraordinary Groves, Burrowings, Mountains and Menageries Todd Longstaffe-Gowan shows how a group of English men and women in the seventeenth to twentieth centuries used their gardens to express and develop their eccentricities. That means, of course, that in addition to describing their wonderfully diverse gardens, he also tells us many juicy bits about the gardeners’ lives. About a year ago, I watched a webinar by James Golden highlighting his garden in New Jersey. Located on a ridge above the Delaware River, I was mesmerized by his photographs, especially his ability to take the best advantage of lighting, without resorting to any noticeable tricks or enhancements.

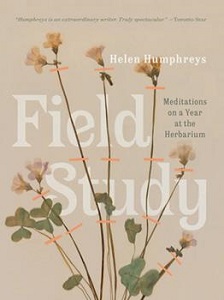

About a year ago, I watched a webinar by James Golden highlighting his garden in New Jersey. Located on a ridge above the Delaware River, I was mesmerized by his photographs, especially his ability to take the best advantage of lighting, without resorting to any noticeable tricks or enhancements. Imagine a plant carefully and dutifully dried, pressed, and preserved between sheets of paper. Now imagine a room full of cabinets and drawers in which are stacked plant upon plant upon plant in this fashion, over 140,000 dried plant specimens in all. It would be a feat of admirable persistence and curiosity to explore every single specimen. Yet, that is exactly the task Helen Humphreys set out to do in writing Field Study: Meditations on a Year at the Herbarium.

Imagine a plant carefully and dutifully dried, pressed, and preserved between sheets of paper. Now imagine a room full of cabinets and drawers in which are stacked plant upon plant upon plant in this fashion, over 140,000 dried plant specimens in all. It would be a feat of admirable persistence and curiosity to explore every single specimen. Yet, that is exactly the task Helen Humphreys set out to do in writing Field Study: Meditations on a Year at the Herbarium. In the preface of

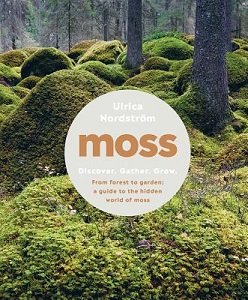

In the preface of  When was the last time you stopped during a walk and looked closely at the tufts of tiny green leaves growing on the sidewalk or on the trunk of a tree or on a humble rock? Have you found yourself staring at a clump of moss in your garden wishing it were gone? If you wish to know more about mosses–and perhaps gain a bit of appreciation for them–this book is for you.

When was the last time you stopped during a walk and looked closely at the tufts of tiny green leaves growing on the sidewalk or on the trunk of a tree or on a humble rock? Have you found yourself staring at a clump of moss in your garden wishing it were gone? If you wish to know more about mosses–and perhaps gain a bit of appreciation for them–this book is for you.

Penstemons are an important genus of native plants throughout the western United States. They have also been hybridized to produce some excellent garden plants, well able to tolerate droughty summer conditions

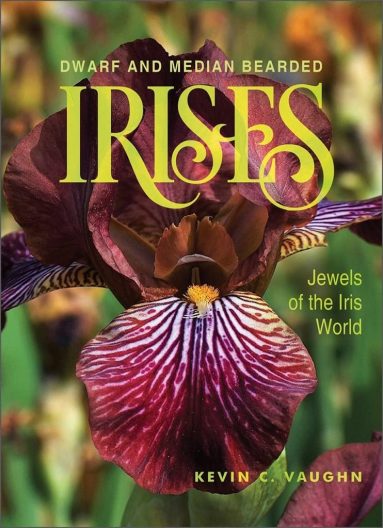

Penstemons are an important genus of native plants throughout the western United States. They have also been hybridized to produce some excellent garden plants, well able to tolerate droughty summer conditions Kevin Vaughn is an active grower and breeder of iris in Oregon. His newest book, “Dwarf and Median Bearded Iris” focuses on the development of varieties smaller than the more familiar tall bearded selections. These are very useful garden plants, as they do not dominate their setting or requiring the staking often needed by their taller cousins. The history of their development may be of interest only to the most devoted iris fan (yes, I’m guilty as charged), but the author balances this with innovative planting designs and good suggestions for companion plants. He also names his favorite varieties and many are available from one of the several iris gardens in our region.

Kevin Vaughn is an active grower and breeder of iris in Oregon. His newest book, “Dwarf and Median Bearded Iris” focuses on the development of varieties smaller than the more familiar tall bearded selections. These are very useful garden plants, as they do not dominate their setting or requiring the staking often needed by their taller cousins. The history of their development may be of interest only to the most devoted iris fan (yes, I’m guilty as charged), but the author balances this with innovative planting designs and good suggestions for companion plants. He also names his favorite varieties and many are available from one of the several iris gardens in our region.