Industrial Worker

|

Report by Chris Perry and Victoria Thorpe

Abstract: The Industrial Worker has been an official newspaper of the Industrial Workers of the World for more than one hundred years. Published first in Spokane, then in Seattle, it remained for more than two decades the voice of the IWW in the Pacific Northwest. In 1931, the newspaper moved to Chicago and continues from that location today. Frequency: weekly except 1921-1925 when it was bi-weekly. 4 pages except for May Day editions of 8 pages. Publisher: the local branch of The Industrial Workers of the World, with the approval of the National Executive Committee. Editors: Collection: University of Washington microfilm A4-A5. Status: Incomplete. Issues between August 1913 and April 1916 are missing. Also between July 1918-April 1919. (Since the publication of this essay, the first four years of the Industrial Worker have been digitized by Marty Goodman of the Riazanov Library Project and can be accessed online at marxists.org.) The Industrial Worker was a four-page newspaper published intermittently out of Seattle and Spokane between March 8, 1909 to November 21, 1931. It was, as was stated in later issues in the top right corner, the official western organ of the I.W.W. It served as an outlet for information regarding the radical movement in general and "wobbly" affairs specifically as they affected the western U.S. Industrial Worker contained local, state, national, and international news about wobbly strikes and policy and the radical movement in general. About sixty percent focused on news affecting the western states. In addition to news, it contained songs, political cartoons, book reviews, job listings, entertainment and fundraising events, advertisements (in the early days), and notices (mostly personal and union position openings). The paper gives insight into agendas and workings of the I.W.W. as well as providing a picture of radical causes and the forerunners of today’s radical press such as Z Magazine and Adbusters. Publishers and Home Cities In the first eleven years of the Industrial Worker’s publication, it moved between Seattle and Spokane four times, even ending up in Everett for a brief time. From March 18, 1909 to December 1,1909 and May 21, 1910 to August 21, 1913 it was stationed in Spokane. From December 15, 1909 to May 14, 1910; April 1, 1916 to July 6, 1918; and July 16, 1919 to November 21, 1931 (when the Industrial Worker moved permanently to the I.W.W. headquarters in Chicago until it’s demise in 1975) it was published in Seattle. There are no records from August 21, 1913 to April 1, 1916. In addition to these, the paper was published for a short time in Everett, from April 25 to July 9, 1919. One possible reason for this movement could be the persecution of the wobblies in this period. In fact that would explain why the paper ceased to be published for almost 3 years. Not only did the place of publishing change often, but the editors were often changing too, with long periods of no editors at all. The first editor that is named in the paper is James Wilson (March 18, 1909-December 15, 1909). He then turned the reigns over to F.R. Schleis (December 25, 1909-May 14, 1910). Next Hartwell S. Shippley (May 21, 1910-Nov 9,1910) took up the project. Shippley then passed the job to Fred W. Hulewood (November 17, 1910-January 25, 1912), one of the only two editors to serve for longer than one year. When Hulewood retired, Walker C. Smith (February 1, 1912-July 10, 1913) resumed as publisher followed by John F. Leheney (July 17, 1913-July 24, 1913) who had the shortest stint, being publisher for only two issues. Following three years of silence, Thomas Whitehead (April 1, 1916-May 6,1916) appeared as publisher when the paper resumed. The last named publisher, J.A. MacDonald (May 13, 1916-July 6, 1918), served for almost two years. He may have served longer but after July 6, 1918, there is no listing of the staff. There are a few possible reasons for all this changing of staff. The first is that during this early part of the I.W.W.’s history, there was an active policy of repression enforced upon the wobblies by the government. The editors may have been arrested and therefore unable to perform their duties. That would explain the lack of staff detail after a certain point. They listing of staff members would make it easy for the police to find members and arrest them. A second possibility could have to do with the philosophy of the I.W.W. At its heart, the I.W.W. was primarily and anarchist organization. The less centralized and established the power of the editor was the better it would reflect the organization. In all likelihood (if the paper was run like the I.W.W. claimed to run) the editor would have had minimal power in the first place, with all editorial decisions made by the collective staff. That would be the ideal situation. Whether it was actually run that way would warrant further research and interviews with the staff. If that was the case, then the editor would be editor in name only and after a certain point, the paper would cease to need one at all, corresponding to the papers cessation of naming the editors. News The news of the Industrial worker was about sixty percent devoted to the western U.S. It contained accounts of strikes, local radical direct action and activism, and other labor and political movements, including socialists and communists, which they seemed to view in a somewhat affectionate light. There was also national and international news about labor and radicalism. There were editorials about wage slavery in China and Mexico next news about national labor law and the I.W.W. as a whole. In addition to the normal news there were a number of special issues. Every year there was a May Day issue that took a step back and looked at the progress of the labor movement and the future. There was a special supplement from March 9, 1918 to April 20, 1918 called the Lumberjack supplement, which was devoted to labor as it related to people in the timber industry. Advertisements In its early years, the Industrial Worker carried many advertisements. Most were for hotels, restaurants, bookstores, and clothiers primarily located in the Seattle area. This seems to suggest that the paper was primarily circulated in this area. Until the end of the 1913 collection usually half of the fourth page of every issue is given over to ads like the following:

Advertisements disappear n the 1920s, reflecting the changing pattern of public opinion after the years of suppression. The I.W.W. had gone from being publicly accepted to having to operate in a more underground manner. This would mean that business would be less likely to want to be associated with the I.W.W or the paper. Job Listings In addition to all the news, there was a section devoted to job news. This was basically reports of working conditions and pay in local areas for use by people looking for employment. The reports dripped with sarcasm and hints at an adversarial relationship with management. An example of this appears in the January 15, 1927 issue of the Industrial Worker:

Another report from the same issue gives some relative wages of the day:

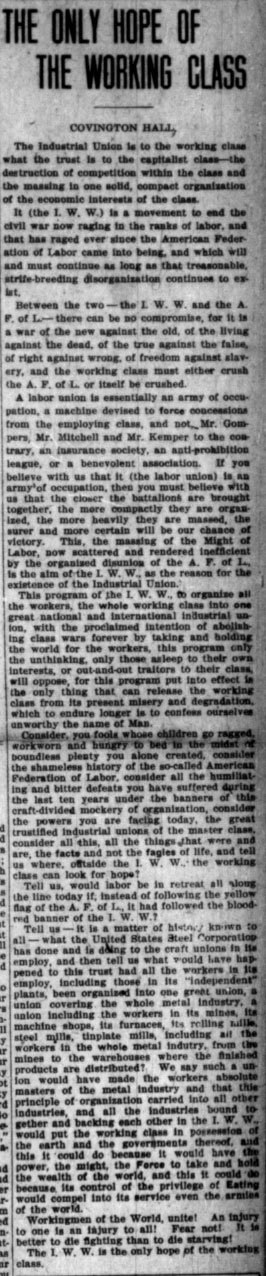

Themes and strategies of The Industrial Worker: 1. Propaganda: A radical, revolutionary paper, the Industrial Worker is characterized throughout by distinct and blatant propaganda. As the voice of the IWW, or at least the Washington branch , the paper aimed to further the development of one big union through the recruitment of all workers. The reader is encouraged to support strikes, to organize and to spread the word. The first issue in particular relies heavily on propaganda rather than reporting. "Dogs, Heaven and Paupers" illustrates the heavy use of sarcasm. This article compares the life of a pet dog with one of the workingman. The dog, unsurprisingly, is portrayed as having an easy life while the workers have nothing. The bitterness is clear in the closing section of the article: "Don’t organize industrially, (more than) one square meal per day would kill you. Keep on working for nothing. Get married if you can and raise some more slaves for the brothels and bread lines." The front page also carries an article entitled "I Had a Dream", another fictional account in which Samuel Gompers is depicted on the right hand of the devil. The organization's antagonism toward the American Federation of Labor is thus clear from the start. The propaganda can also be extremely subtle. Whenever a worker is referred to, in any issue, the name is prefixed with "fellow worker" thus enforcing the message of solidarity at every opportunity. Some of the cleverest examples of IWW propaganda are the slogans and mottos that appear in all of the every issues until July 17, 1913.. The following is a selection:

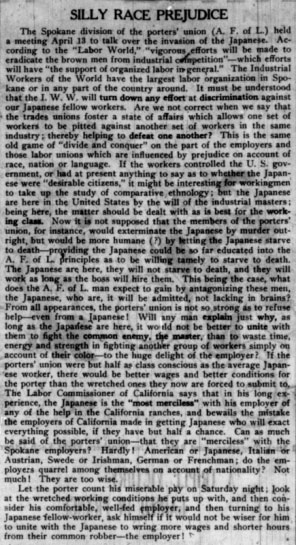

2. Solidarity As the slogans above illustrate, solidarity, as the "one main weapon" is a subject that is emphasized throughout. One of the most striking aspects of the paper is its inclusiveness for all workingmen regardless of craft or ethnicity. The AFL is frequently berated for its failure on both of these issues. In the first issue of The Industrial Worker there are articles in both Italian and German. Later issues carry articles in Polish and French. On May 13 1909 the paper champions those of Japanese ethnicity, an extremely unusual stance at this time. Readers are asked, "who’s robbed you last; your boss or some Japanese?"…."Men may come and men may go but the broad principal of working class unity will last after all other theories have been forgotten. The class struggle is a fact. Are you struggling to the best of your ability or are you trying to work yourself into the enemies camp by betraying your fellow workers?" Although the views on Japanese labor are the most remarkable in light of the anti Japanese sentiment of the period, efforts made to make the paper accessible to other recent immigrants are also significant. The IWW Press column lists affiliated papers in foreign languages. A Bermunkas, (The Wage Worker, Hungarian) Darbunuku Balas, (The Voice of the Worker, Lithuanian) Het Licht, (The Light, Flemish) Il Proletari, (The Proletariate, Italian) El Rebelde, (The Rebel, Spanish) Rabochaya Rrch. (Voice of Labor, Russian) A Jewish Industrial Worker is also included on the list. News from labor struggles around the rest of the country and also in Europe is included frequently; increasing the sense of solidarity the Industrial Worker’s authors sought to inspire. International labor news, known as "Translated News," particularly from Russia and France, is a feature that with few exceptions occupies roughly one third of page three from February 1, 1912 until the publication moves to Chicago at the beginning of 1930. Articles such as "French Unionism: A Militant Power" and La Belle France" are common through to the end of the 1913 editions while support for Russia is strongest through the Russian Revolutionary period. On November 26, 1926 for example, it is reported, that Russians unions have sent British mine workers $1, 250,000 to aid them in their strike. The principal of aiding fellow workers in their action, (hence "an injury to one is an injury to all") can also be seen through requests in the paper for financial aid to strikers and also requests that strikers stay away from areas where industrial action is taking place. In the July 15, 1916 issue, a strike by IWW miners against the U.S. Steel Trust, in Illinois, is referred to as a "Declaration of War." Members are asked for donations and reminded that: " This is your fight. You must raise money for food, clothing shelter and organizational work." Above the Title Industrial Worker on June 20, 1912, the headline reads: "Do not ship to the Canadian northern, or to White Salem, Washington. Big Strikes on." 3. Religion. In the first issue, March 18, 1909, evangelist Billy Sunday is berated on the grounds that he asks for money from those who don’t have it, i.e. the workers. The Reverend W. B. Bull is criticized on page three of the same issue and called a dangerous man. More anti religious sentiment is displayed on May 13, 1909 when the priests are accused of "upholding the justice of legalized murder….The delusion of patriotism and the deceit of the priests and the preachers serve to cause race hatred and to divide the workers…" Although the issue of religion is not a major topic of the paper, it is generally portrayed negatively. A cartoon on the front page of February 12, 1927 issue depicts a graveyard with angel wings above and a question mark where the body of the angel would normally be. The inference being that an afterlife is doubtful. At times the newspaper will caution that talking about religion divides workers, as it did on July 9, 1909: " questions of religion, of race, of color, of nationality are…firebrand scum among the workers to keep them from fighting the bosses.." But headlines like "The Priest aids the Boss" revealed the core sentiments of the the writers who produced The Industrial Worker.

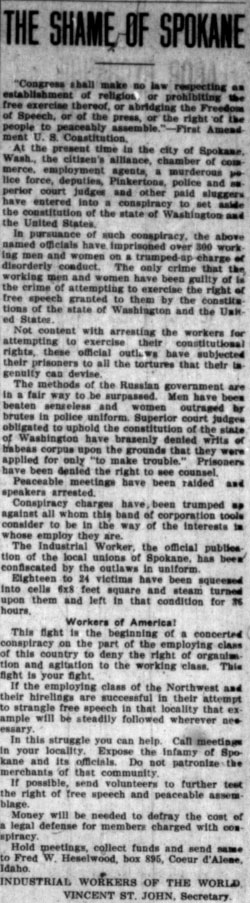

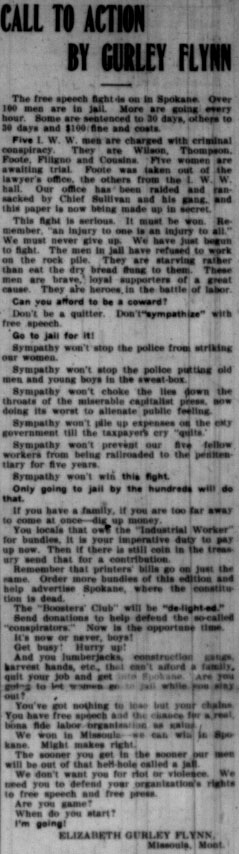

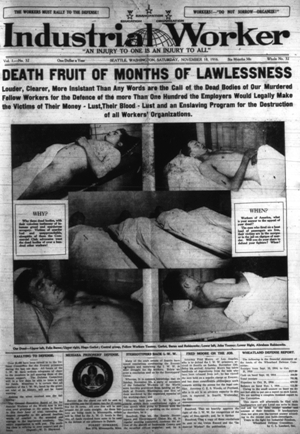

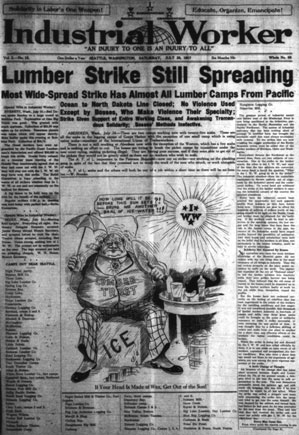

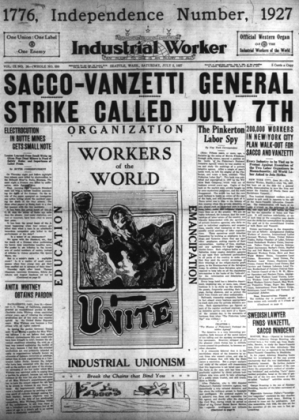

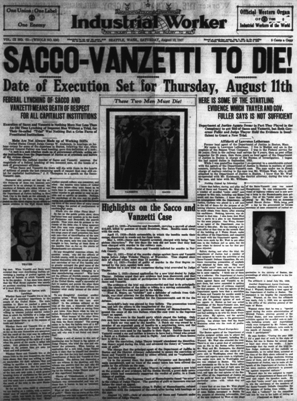

Major Stories 1. Spokane Free Speech Fight. This protest involved members of the union violating a city ordinance, which forbid speaking on street corners, many members chained themselves to lampposts and recited the declaration of Independence. Hundreds of union members were jailed while the Industrial Worker encouraged those who could to come to Spokane to join them. The dispute lasted from November 1909 until late March, 1910. Although the dispute was officially ended when the Washington legislature resolved to legislate against the practices of employment sharks, men remained in jail. The Industrial Worker called readers attention to this by pasting updates along the top of the first page. During the dispute, the free speech fight made the front page, every week from November 10, 1909 until March 12, 1910. The issue continued in prominence as key members were convicted on June 29, 1910. 2. Ettor and Giovannitti, Articles begin, June 20, 1912.: 3. Lumberjack strike. Conducted by the IWW. The Industrial Worker calls this "their most successful strike in history" until America’s entry into World War One. Coverage in the newspaper appears from July 28, 1917. From March 9, 1918 until April 1920 a Lumberjack supplement was issued in accompaniment to the paper. The surviving copies are in poor condition however. Only the issue printed on April 27, 1918 is complete. 4. Everett Massacre, November 11, 1916, November 18, 1916( includes graphic photographs on the front page.) The incident began with a Free Speech fight conducted by the IWW. As supporters sailed to Everett from Seattle they were met on the docks by armed police. Five workers and two policemen were killed, while a total of fifty men were wounded. Although the workers were acquitted, this was the last major free speech fight in the Pacific Northwest at least. 5. Sacco and Vanzetti Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were arrested outside Boston in 1920 and charged with robbing and killing a shoe factory paymaster and his guard. Though a prosecutor insisted they would be tried for murder and "nothing else," their radical politics remained a focus of the 1921 trial. Judge Webster Thayer, whose bias against the two men surfaced repeatedly, denied the first motion for a new trial in October 1924. In the years that followed he would deny five other motions. In late 1925, new evidence surfaced that gave the Sacco-Vanzetti defense new grounds for an appeal: a convicted murderer told Sacco he committed the South Braintree murders. But Thayer again denied the motion for a new trial, finding that the confession was untruthful. The battle to save Sacco and Vanzetti ended when they were executed in the electric chair on August 23, 1927. In the months leading up to the execution, every issue of the Industrial Worker contained an update on the two including calls for strikes, editorials on the trials and the authorities involved, and even comments by the convicted anarchists. One of the most moving pieces is a poem by the two, called "Last Will": Prologue: To Wit: And Lastly: To those who judge solely seeking renown, In the issue after the execution there was a full page memorial to the two fallen martyrs. It contained a final editorial on the trial and the last message written by Vanzetti.

Editors and Contributors

Funding Little information is detailed on funding or circulation of the Industrial Worker. Subscriptions are offered for six months or one year. By May 30, 1925 the cost of one years subscription is $4, however this is reduced June 6, 1925 due to falling circulation. Although little information is given on the funding of the paper, the May 24 issue, 1924 indicates that the circulation has slackened. An appeal is lodged to the membership to increase the circulation or " serious loss to power will be felt." The article notes a change since the previous year. "Less than a year ago, IW has been bearing the larger part of the cost of the Equity Printing Company. Today- and for the last few months, it has been the other way around." A year later, on May 30, 1925, the subscription cost halved as the Industrial Worker shifted from a bi-weekly to weekly publication schedule. Since April 23, 1921 the paper had been issued twice per week., the intention was announced to reduce output to once per week. Widespread unemployment was blamed and it appears that the paper owed its survival to donations. Over the previous four months Seattle branches of the IWW contributed $2000 while other branches put forward almost $1000.

Appendix A Contents of the Industrial Worker microfilm file A4, A5. A4: March 18, 1909- February 10, 1910 February 10, 1910- August 1913 A5: April 1916- July 1918 April 1919- July 1919 July 1919- April 1921 April 1921- April 1924 April 1924- December 1926 January 1927- December 1929 |

Click to enlarge

The Industrial Worker, the official newspaper of the Industrial Workers of the World in the West, outlined the IWWs radical vision with slogans like "The working class and the employing class have nothing in common," and the popular "An Injury to One is an Injury to All." Additionally, the paper reported on many progressive issues and events important to workers and radicals.

Unlike the conservative AFL, the IWW reached out to the thousands of unskilled transients who worked in the seasonal industries in the West. Without permanent homes, these men who rode the rails and tramped were known by many different names: harvest hands, bindle stiffs, hobos. For a mere two dollars, any worker, regardless of skill level, vocation, or race could join the IWW. Propaganda

The Industrial Worker did not just rely on news articles to spread its revolutionary message. Songs, cartoons, fiction, and poems also filled its pages, arguing that the revolution was near. Solidarity

The IWW was ahead of its time in terms of race relations. Wobblies believed that racial divisions only detracted workers from the revolutionary struggle. Instead of fighting each other over questions or race, IWW leadership argued, workers should be fighting the bosses. Above: the IWW preamble in Japanese. Below: an article on race prejudice.

Spokane Free Speech Fight

When Spokane city authorities prohibited IWW members from publicly speaking out against the employment sharks, the call went out over the Industrial Worker for Wobblies to come and flood the city. In a matter of weeks, thousands of Wobblies filled the streets and jails of Spokane. Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, a leader in the IWW and one of its most well known members, was only 19 years old when she led the Spokane Free Speech Fight. Everett Massacre

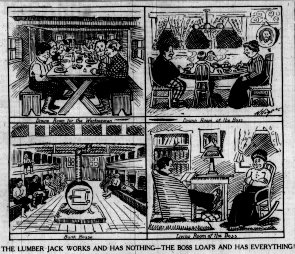

When a group of Wobblies, traveling by boat, went to Everett to aid in a free speech fight, they were met by the police and vigilantes. Five IWW members were killed in a shootout. Here, the Industrial Worker published pictures of their corpses, although the editors reminded their readership: "Don't mourn, organize!" The Timberbeasts

In the logging industry, where working conditions were dangerous, living conditions detestable, and wages poor, the IWW found some of its most ardent, radical, and dedicated members. Some of the IWWs largest, and most successful strikes occurred in the logging industry. Sacco and Vanzetti

Although not IWW members, the editors of the Industrial Worker reported frequently on the Sacco and Vanzetti case, calling for strikes and boycotts in the weeks leading up to their execution.

|

|

Copyright (c) 2001 by Chris Perry and Victoria Thorpe |

|

--Oct.%207,%201909--p.4.%20300W%20jpg.jpg)

--April%2029,%201909--p.4.%20300W.jpg)