Report by Josh

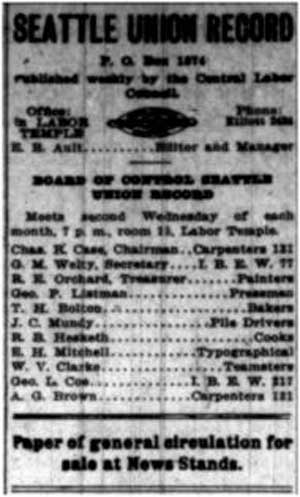

Kaplan

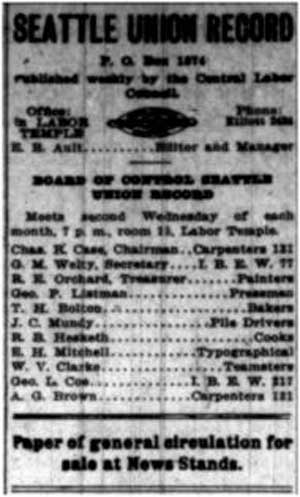

The Seattle Union

Record was a major Seattle area labor newspaper of the early

twentieth century. With a publication run of nearly thirty years, the paper was a voice of labor during a dynamic period of Seattle’s labor history.

Published by the Seattle Central Labor Council (and its predecessor, the

Western Central Labor Union, until 1905), the Union Record was a

full coverage newspaper, not merely a newsletter of the CLC. The paper’s

broad coverage of local, national, and international events provides insight

into the attitudes of Seattle’s working people and helps us understand the

world they lived in.

This report studies The Seattle Union Record from January 20, 1912

through November 28, 1914. George T. McNamara was the editor and manager of

the Union Record at the beginning of this period, but beginning with the

April 12, 1913 edition, Harry B. Ault assumed this position. The following

review will discuss the paper’s overall characteristics, its intended

audience, its regular features, its typical layout, and its overall

message. This review will also describe the Union Record’s coverage

of major events in this time period and evaluate the stance the paper took

on many issues.

Organization of the Seattle Union Record

While the Seattle Union Record was indeed a full coverage newspaper

that contained articles about major national and international issues, its

organization shows that it was clearly geared towards union members. The

second page of every edition was headlined with “Co-operation Means

Success,” a phrase that often graced the top of additional pages as well.

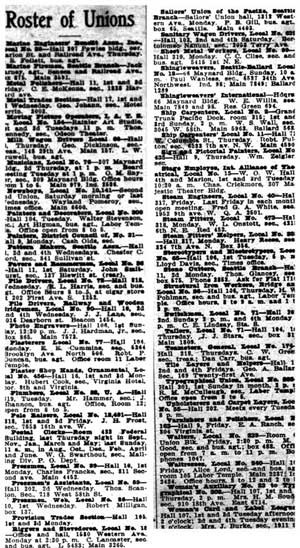

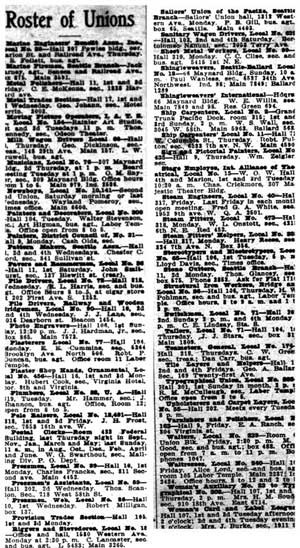

The paper also featured several regular weekly sections dedicated to other

labor councils based in the Seattle Labor Temple. A full page was dedicated

to the Building Trades Council and another, smaller section, titled the

“Weekly Department of Women’s Label League, was dedicated to local women’s

labor events. In the middle pages of the paper, readers found both the

“Directory of Labor Organizations” and a “Roster of Unions”, which provided

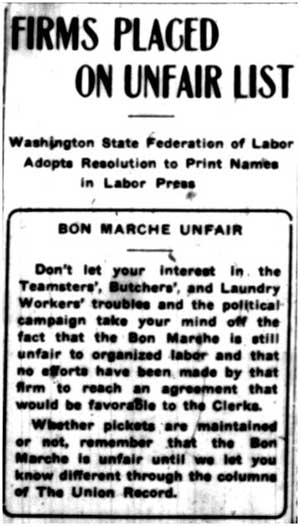

the contact addresses for a large number of locals. . A particularly

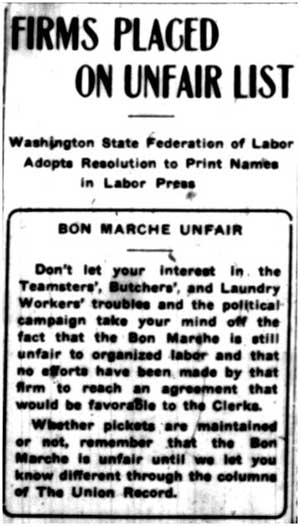

interesting feature of the paper was its “Unfair List”, a constantly updated

list of local businesses which maintained business or hiring practices

deemed unfair to labor. The Union Record also reserved space for an

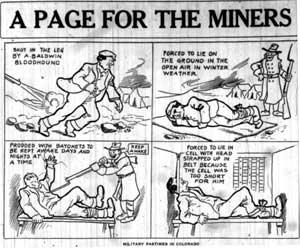

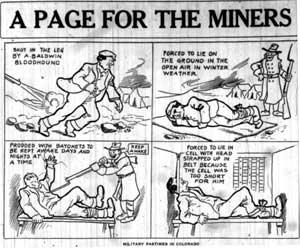

editorial page and frequently featured cartoons. In 1914, the paper began

to run a regular section entitled “A Page for the Miners,” in response to

the violent struggles of mine workers in Colorado and Michigan. These

“Miners’ Pages” contained stories about the mine workers, cartoons, and

messages of solidarity. Indeed, the expressions of solidarity expressed on

these pages reflected The Seattle Union Record’s ongoing commitment

to build bonds between all varieties of working people.

Advertising to the workingman Just like

traditional newspapers, advertising had a significant presence in the

Union Record. . The range of products and services that advertised to

the union crowd covered most every good and service imaginable. One

similarity among the many advertisements was the wording and symbols

companies used to tout their union friendly practices or exclusive use of

union labor. An interesting ad for the Black and White Hat proudly declared

their hats to be “The man kind”. Such wording was used to appeal to the

manly pride of workingmen. McCormack Bros. proclaimed that their “clothes

are honor-made and sold by card men,” another appeal to the honor and

dignity of workingmen. Lawrence Morgan advertised their union made cigars

with a more straightforward approach, declaring simply that “They Are Good”. Leisure

activities were also advertised. The J. & H. Bar on Occidental Ave.

advertised wines, liquors and cigars under the banner of “The Only Strictly

Union Saloon in the City” and continued with “we are union from basement

floor to chimney top.” For the union man looking to end a hard day with

dancing, Dreamland on 7th and Union St. claimed to be “the only Union

Dancing Pavilion in Seattle.” If drinking at home had more appeal, Rainer

Beer advertised itself as “a fountain of health and happiness”. One can only

assume this was the early 20th century’s version of beer ads featuring girls

in bathing suits washing cars, dancing, or partying on the beach. Advertisements were not

only geared towards men. A “great premium offer” for a lot in the aqueduct

city tract was promised to “the most popular lady member of organized labor”

as part of a contest for women who purchased a yearlong subscription to the

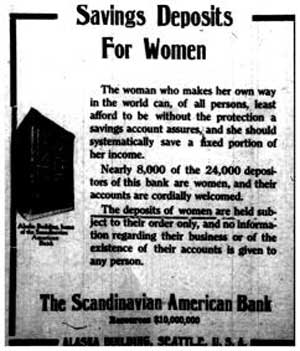

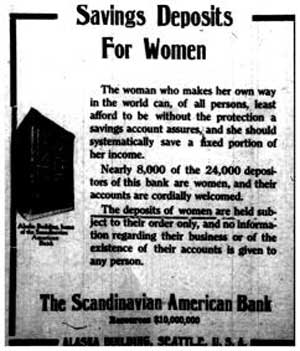

Union Record for $1. The Scandinavian American Bank advertised savings

deposits for women, using the same appeal of pride and honor, yet geared

towards the working woman. “The woman who makes her own way in the world”

was encouraged to open an account, and the bank proudly declared that

“nearly 8,000 of the 24,000 depositors of this bank are women.”

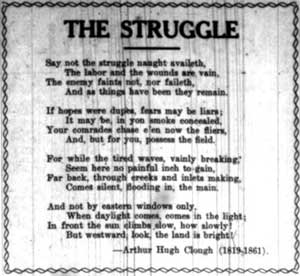

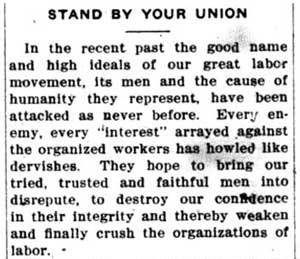

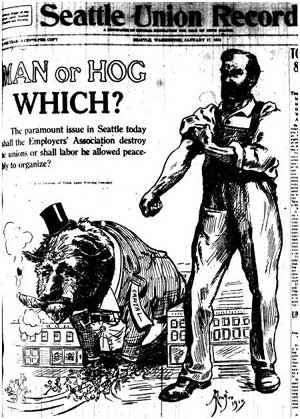

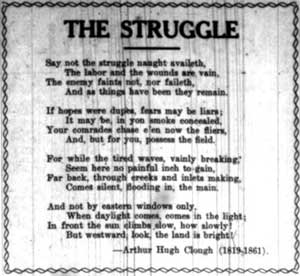

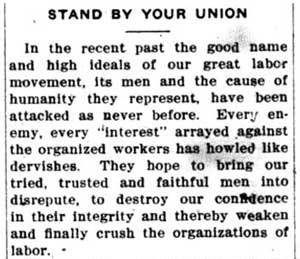

The message of the Seattle Union Record Solidarity is

perhaps the theme that best defines the message of the Union Record.

More than simply conveying the news, the paper served as a rallying cry for

the labor movement and union men and women as a whole. Stories frequently

challenged readers to stand up and take action, or fulfill their duties to

the labor movement. Stories depicted most issues in the context of the

greater struggle between justice seeking working people and tyrannical

employers. To this end, articles supported working-class activism and

championed workers’ sense of decency, principle, pride, and honor. In a

short article titled “Men with Principle, or Principle without Men?” the

paper expressed its support for Paul Mohr and George McNamara, two union men

running for city council, by stating that “those among our citizens desiring

constructive legislation along right lines will make no mistake in voting

for men who created principles and are the builders of their own platforms…”

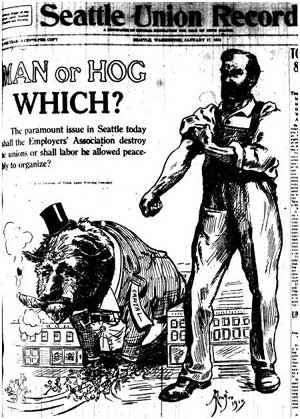

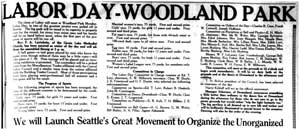

(02/03/1912) A cover page from July, 1914 inviting workers to the weekly

Labor Temple Meeting also conveyed this theme. In bold print, the headline

exclaimed, “Solidarity – Labor Forward,” and the subtitle below read, “The

Watchword Is “Solidarity.” (07/11/1914) Another

consistent theme of the paper was its use of language that portrayed the

issues of the day in the terms of class war. There was also no illusion of

unbiased coverage. The Union Record almost always took a strong and

clear stance on the stories it covered. Employers supportive of anti-union

legislation, other actions that undercut the labor movement, or otherwise

unfriendly to workers were characterized as evil and assailed as enemies of

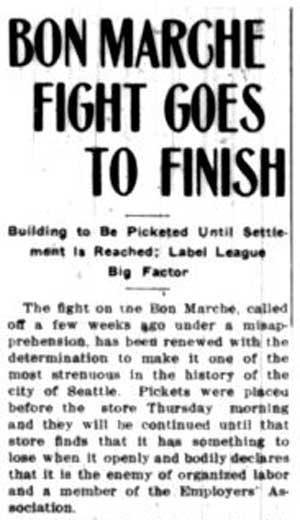

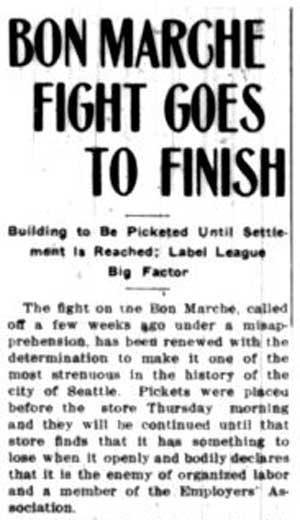

the readers. During a campaign against the Bon Marche, a popular Seattle

department store, for unfair labor practices, an article titled “Shall the

Weak Bear the Burden?” stated that “the fight against the Bon Marche is a

fight for those who cannot help themselves.” (April 26, 1913) One cover page

story, “Ballard Shingle Weavers Again Revolt” decried the industry in

question as a “strong-hold of non-unionism” and called for fellow union

members to support their brothers. Another headline on this same cover cast

the honorable union man as a fighter against the unjust. “Clerks Fight

Against Exploitation of Weak” began by framing the conflict as another

uphill fight of the David of labor versus the Goliath of unjust employers,

claiming “times without number are the vigilant workers of organized labor

confronted with the doubting”. (April 12, 1913) Time and time again, The

Seattle Union Record evoked the rhetoric of class conflict and class war

to argue that solidarity was necessary for workers to establish a just and

fair society. With such an

emphasis on working-class pride and honor , the Union Record was

understandably unkind to men it considered dishonorable, cowardly or

unprincipled. An article titled “Man with the Yellow Streak” was unabashedly

critical of such men and called on readers to avoid associating with these

sorts of individuals.

“Never choose a man who has a yellow streak to be your friend; never permit

yourself to follow a man that carries the yellow, regardless of how loud he

may shout and the grievances he may rave about. Such men are dangerous and

treacherous; he will coach you on and desert at the first scent of a real

fight.… He can’t help himself, because he isn’t man enough to own up and ask

for assistance. He won’t tell you what is wrong with him. He wears the

velvet of false pride over his threadbare patch, and you only see it when

it’s too late and his cloak drops and shows his tattered courage.” (April

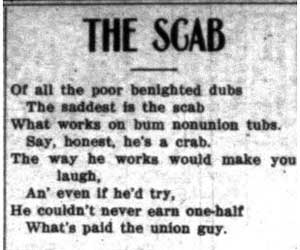

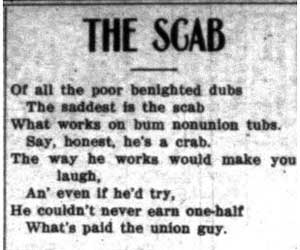

12, 1913) Scabs, the name given to

strike breakers and nonunion laborers, were portrayed as the lowest form of

enemy to the labor movement. In a headline article titled “Scabs Shipped

Out,” the subtitle declared that the “Captain in charge of troops in

Trinidad District turns back five degraded specimens of humanity who attempt

to scab.” (May 16, 1914) One was likely certain to readers of the Union

Record: being on the bad side of the paper’s staff was a distinction to

be avoided.

Race and gender in the Union Record Early

twentieth century Seattle workers and unions were constantly divided over

questions of race and gender. While some factions argued that racism and

sexism were tools used by employers to divide the working-class and workers

should be fighting the bosses and not themselves, others believed that

working-class solidarity was the privilege of whites. . But surprisingly,

the Union Record had little to say about race relations. The article

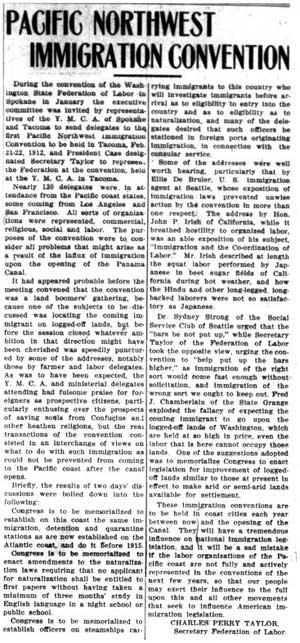

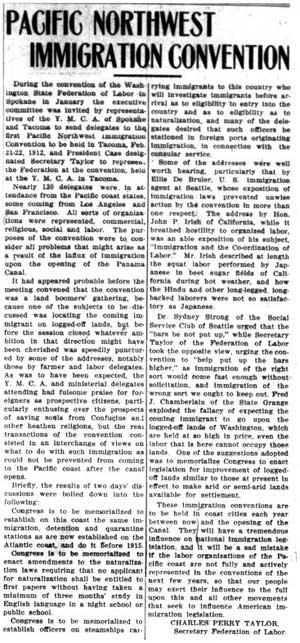

“Pacific Northwest Immigration Convention”, written by Charles Perry Taylor,

was a summation of events at a meeting about the place of foreign-born and

nonwhite workers in the labor movement.. Taylor wrote that speakers

“described at length the squat labor performed by Japanese in beet sugar

fields of California during hot weather, and how the Hindu and other

long-legged long-backed laborers were not so satisfactory as the Japanese.”

(March 2, 1912) As this article shows, Asians were the target of negative

attitudes and racist opinions. But overtly racist articles were relatively

rare, and occasionally a writer took a position against Anti-Asian bigotry,

as in the March 1913 piece titled “Rainier Beach after the Japs.” The

article critiqued the Rainier Beach Improvement Club’s attempt to

discriminate against Japanese immigrants and sought to expose “the lie…that

there is no anti-Jap feeling in Seattle.” Black workers

were generally portrayed positively in the Union Record. In fact,

the paper argued that solidarity between white and black workers was strong

and they had a common enemy in employers. A piece in the September 13, 1913

editorial section titled “Organized Labor and the Negro” included very

inclusive language intended to bond white and black laborers together.

“…white workers need not fear unfair competition from him for the job, as

the Negro would not be satisfied with any less bearable conditions than his

white brother. The result of this action on the part of the unions has been

the formation of many Negro organizations, especially in the southern

states, where are being developed hundreds of skilled Negro mechanics who

take second place to none.” … “There is room in the labor movement for

all workers, whether white, brown, black or yellow, just as soon as any of

them desire to become part of it.” (September 13, 1913)

Overall it seems that the

Union Record was inconsistent when it came to race. On one hand, the

paper used racist and divisive language and held many bigoted opinions. But

on the other hand, it also frequently decried racism and sought to

strengthen white-black working-class solidarity. For the most

part, women were treated with respect in the Union Record. Not only

was there a special section dedicated to the local women’s labor group,

articles frequently paid respect to the women who fought alongside men for

the cause of labor. One such example appeared in the May 30, 1914 edition

under the title “Economic Organizations of Women Great Driving Power.” The

article stated that “Label Leagues [are] of inestimable value in obtaining

better working conditions” and continued that “there have been many great

women in history, women who have risen above convention, custom and

precedent, and left their mark indelibly upon the period in which they

lived.” (March 30, 1914) From the perspective of the paper, women’s

purchasing power and willingness to stand up to the bosses gained them a

great deal of reverence and respect.

The Bon Marche Dispute During the

1912-1914 period, a struggle between workers and the Seattle retailer, the

Bon Marche, was covered in great detail in the Union Record—in fact,

barely a week went by without an article discussing this dispute. An article

titled “Bon Marche Adds Insult to Injury” commented on statements the

retailer issued to its employees. The article began by reprinting a message

the Bon March printed on envelopes it issued to its workers:

“Don’t be one of those who are always ready to fight for their ‘right.’ This

‘rights’ business is a joke. Some people feel offended if they are asked to

do part of another’s work, or if anything not essentially part of their

particular duties is asked of them. Don’t worry so much about your ‘rights,’

but use ‘horse sense.’ You won’t lose anything by having a reputation for

being ‘willing.’ It doesn’t sound smart, but that little word ‘success’ is

bound up in it.”

-THE BON MARCHE April 5th, 1913

Inside the envelope was the $5 weekly wage the Union Record deemed unfairly

low. In January of 1914, the piece titled “Bon Marche Shows Its Teeth”

alerted readers to a notice placed in every window of the Bon Marche that

stated “This firm is a member of the Employers’ Association

and Employs its help For Efficiency Only.” (January 10, 1914) Two weeks later an article stated that the “building

[will] be picketed until settlement is Reached; Label League Big Factor”

(January 24, 1914) Following the resolution of the long-standing

disagreement, the Bon Marche appeared to swallow its pride and agree to

union demands—in fact, the May 30, 1914 printing of the Record included an

advertisement for the store. Given the strength and size of the labor

movement in Seattle, it is understandable that the Bon Marche sought to

regain lost union customers as quickly as possible. And while the add never

admitted to unfriendly labor policies, it did feature the logo for the

union made Black Bear Overalls brand.

Other businesses also employed the tactic of courting union members after

labor disputes had been settled. Kristoferson’s Dairy was called out as

unfair in the February 3, 1912 edition, gaining mention in a small article

titled “Unfair Dairies and Why.” In the April 20, 1912 printing the paper

“had the pleasure of announcing” that Jersey Dairy and Kristoferson’s were

removed from the unfair list. Shortly after, ads for Kristofferson began

appearing in the paper. Examples such as these

show that Seattle’s labor movement had a good deal of power at this

time. They also show that the Union Record played an important role

in coordinating and organizing boycotts against unfair employers.

The Colorado Mine Strikes Perhaps the

most heavily covered national labor news of this time involved the plight of

striking miners in Colorado and Michigan. Upset over horrid conditions and

abysmal wages, mine workers demanded changes from mine owners. The addition

of the “Page for the Miners” section guaranteed weekly coverage of these

strikes. In a March 7, 1914 article titled “Power of Calumet & Hegla Co.”,

special correspondent Arthur Jensen questioned the unchecked economic and

political of copper mine owners. “We have seen the local leaders of the

Progressive party, the Republican governor of the state, the Democratic

leaders of the House committee, the local business men and the New York

detective agencies meekly bow to the strong will of the copper companies”

wrote Jensen. Indeed this important event involved all levels of government

and was of chief concern to the labor movement as a whole. The Union

Record’s constant coverage of the events was typical of the paper’s

commitment to labor causes, large or small.

Voice of a Movement

The Seattle Union Record

is an important part of Seattle’s labor history. Its pages highlight many

major labor issues of the early twentieth century. It provides the context

for major national and international issues and is also a remarkable lesson

in Seattle history. Above all else, the Seattle Union Record gave the

labor movement a voice and helped workers stay connected to national and

international issues..

|

Click to enlarge

(May

2, 1914)

(April

12, 1913)

(January

17, 1914)

(April

19, 1913)

(April

12, 1913)

The Seattle Union

Record was a major Seattle area labor newspaper of the early

twentieth century. With a publication run of nearly thirty years, the paper was a voice of labor during a dynamic period of Seattle’s labor history.

The Seattle Labor

Movement

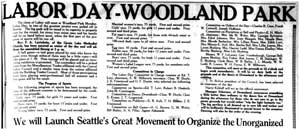

The primary purpose of the

Seattle Union Record was to report on local union news. The

paper contained articles about struggles, strikes, and lockouts.

The paper also laid out the political platform of Seattle's labor

movement.

(September

13, 1913)

(February

24, 1912)

(January

20, 1912)

(February

17, 1912)

(March

16, 1912)

(September

5, 1914)

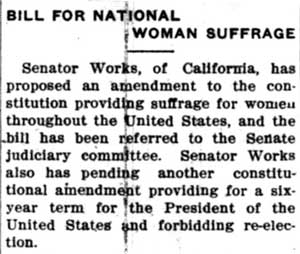

Race, Gender, and

Immigration

The Seattle Union Record

stressed working-class solidarity. Articles argued that workers

could not afford to be divided on issues of race and ethnicity.

The paper also highlighted women's role in the labor movement and ran

articles in support of suffrage and women's rights.

(May

10, 1913)

(March

2, 1912)

(February

28, 1914)

(March

16, 1912)

(May

30, 1914)

The Bon Marche Campaign

During the 1912-1914

period, a struggle between workers and the Seattle retailer, the Bon Marche, was covered in great detail in the Union Record—in

fact, nearly a week went by without an article discussing this dispute.

(May

24, 1913)

(January

10, 1914)

(January

24, 1914)

(February

7, 1914)

Supporting The Miners'

Struggle

Perhaps the most heavily covered national labor news of this time

involved the plight of striking miners in Colorado and Michigan. Upset

over horrid conditions and abysmal wages, mine workers demanded changes

from mine owners. The addition of the “Page for the Miners” section

guaranteed weekly coverage of these strikes.

(March

21, 1914) |